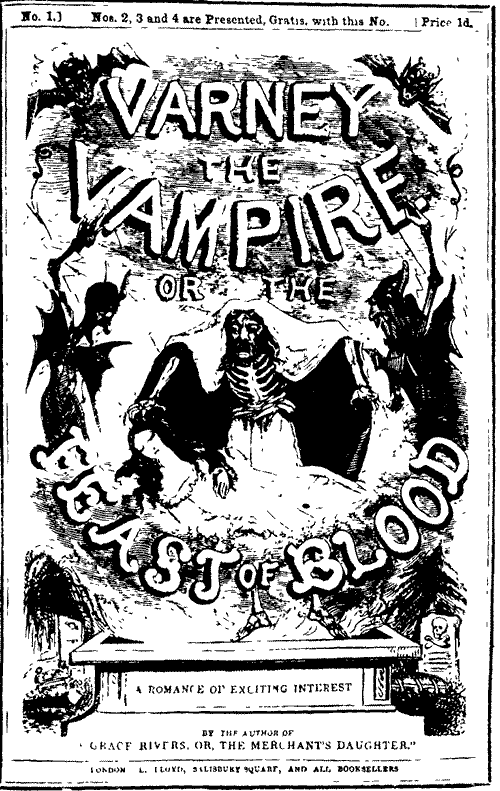

Varney the Vampire; Or, the Feast of Blood

Summary

Play Sample

They now made their way to the chamber of Flora, and they heard from George that nothing of an alarming character had occurred to disturb him on his lonely watch.The morning was now again dawning, and Henry earnestly entreated Mr. Marchdale to go to bed, which he did, leaving the two brothers to continue as sentinels by Flora's bed side, until the morning light should banish all uneasy thoughts.

Henry related to George what had taken place outside the house, and the two brothers held a long and interesting conversation for some hours upon that subject, as well as upon others of great importance to their welfare.It was not until the sun's early rays came glaring in at the casement that they both rose, and thought of awakening Flora, who had now slept soundly for so many hours.

CHAPTER VI.

A GLANCE AT THE BANNERWORTH FAMILY.—THE PROBABLE CONSEQUENCES OF THE MYSTERIOUS APPARITION'S APPEARANCE.

Having thus far, we hope, interested our readers in the fortunes of a family which had become subject to so dreadful a visitation, we trust that a few words concerning them, and the peculiar circumstances in which they are now placed, will not prove altogether out of place, or unacceptable.The Bannerworth family then were well known in the part of the country where they resided.Perhaps, if we were to say they were better known by name than they were liked, on account of that name, we should be near the truth, for it had unfortunately happened that for a very considerable time past the head of the family had been the very worst specimen of it that could be procured.While the junior branches were frequently amiable and most intelligent, and such in mind and manner as were calculated to inspire goodwill in all who knew them, he who held the family property, and who resided in the house now occupied by Flora and her brothers, was a very so—so sort of character.

This state of things, by some strange fatality, had gone on for nearly a hundred years, and the consequence was what might have been fairly expected, namely—that, what with their vices and what with their extravagances, the successive heads of the Bannerworth family had succeeded in so far diminishing the family property that, when it came into the hands of Henry Bannerworth, it was of little value, on account of the numerous encumbrances with which it was saddled.

The father of Henry had not been a very brilliant exception to the general rule, as regarded the head of the family.If he were not quite so bad as many of his ancestors, that gratifying circumstance was to be accounted for by the supposition that he was not quite so bold, and that the change in habits, manners, and laws, which had taken place in a hundred years, made it not so easy for even a landed proprietor to play the petty tyrant.

He had, to get rid of those animal spirits which had prompted many of his predecessors to downright crimes, had recourse to the gaming-table, and, after raising whatever sums he could upon the property which remained, he naturally, and as might have been fully expected, lost them all.

He was found lying dead in the garden of the house one day, and by his side was his pocket-book, on one leaf of which, it was the impression of the family, he had endeavoured to write something previous to his decease, for he held a pencil firmly in his grasp.

The probability was that he had felt himself getting ill, and, being desirous of making some communication to his family which pressed heavily upon his mind, he had attempted to do so, but was stopped by the too rapid approach of the hand of death.

For some days previous to his decease, his conduct had been extremely mysterious.He had announced an intention of leaving England for ever—of selling the house and grounds for whatever they would fetch over and above the sums for which they were mortgaged, and so clearing himself of all encumbrances.

He had, but a few hours before he was found lying dead, made the following singular speech to Henry,—

"Do not regret, Henry, that the old house which has been in our family so long is about to be parted with.Be assured that, if it is but for the first time in my life, I have good and substantial reasons now for what I am about to do.We shall be able to go some other country, and there live like princes of the land."

Where the means were to come from to live like a prince, unless Mr. Bannerworth had some of the German princes in his eye, no one knew but himself, and his sudden death buried with him that most important secret.

There were some words written on the leaf of his pocket-book, but they were of by far too indistinct and ambiguous a nature to lead to anything.They were these:—

"The money is —————"

And then there was a long scrawl of the pencil, which seemed to have been occasioned by his sudden decease.

Of course nothing could be made of these words, except in the way of a contradiction as the family lawyer said, rather more facetiously than a man of law usually speaks, for if he had written "The money is not," he would have been somewhere remarkably near the truth.

However, with all his vices he was regretted by his children, who chose rather to remember him in his best aspect than to dwell upon his faults.

For the first time then, within the memory of man, the head of the family of the Bannerworths was a gentleman, in every sense of the word.Brave, generous, highly educated, and full of many excellent and noble qualities—for such was Henry, whom we have introduced to our readers under such distressing circumstances.

And now, people said, that the family property having been all dissipated and lost, there would take place a change, and that the Bannerworths would have to take to some course of honourable industry for a livelihood, and that then they would be as much respected as they had before been detested and disliked.

Indeed, the position which Henry held was now a most precarious one—for one of the amazingly clever acts of his father had been to encumber the property with overwhelming claims, so that when Henry administered to the estate, it was doubted almost by his attorney if it were at all desirable to do so.

An attachment, however, to the old house of his family, had induced the young man to hold possession of it as long as he could, despite any adverse circumstance which might eventually be connected with it.

Some weeks, however, only after the decease of his father, and when he fairly held possession, a sudden and a most unexpected offer came to him from a solicitor in London, of whom he knew nothing, to purchase the house and grounds, for a client of his, who had instructed him so to do, but whom he did not mention.

The offer made was a liberal one, and beyond the value of the place.The lawyer who had conducted Henry's affairs for him since his father's decease, advised him by all means to take it; but after a consultation with his mother and sister, and George, they all resolved to hold by their own house as long as they could, and, consequently, he refused the offer.

He was then asked to let the place, and to name his own price for the occupation of it; but that he would not do: so the negotiation went off altogether, leaving only, in the minds of the family, much surprise at the exceeding eagerness of some one, whom they knew not, to get possession of the place on any terms.

There was another circumstance perhaps which materially aided in producing a strong feeling on the minds of the Bannerworths, with regard to remaining where they were.

That circumstance occurred thus: a relation of the family, who was now dead, and with whom had died all his means, had been in the habit, for the last half dozen years of his life, of sending a hundred pounds to Henry, for the express purpose of enabling him and his brother George and his sifter Flora to take a little continental or home tour, in the autumn of the year.

A more acceptable present, or for a more delightful purpose, to young people, could not be found; and, with the quiet, prudent habits of all three of them, they contrived to go far and to see much for the sum which was thus handsomely placed at their disposal.

In one of those excursions, when among the mountains of Italy, an adventure occurred which placed the life of Flora in imminent hazard.

They were riding along a narrow mountain path, and, her horse slipping, she fell over the ledge of a precipice.

In an instant, a young man, a stranger to the whole party, who was travelling in the vicinity, rushed to the spot, and by his knowledge and exertions, they felt convinced her preservation was effected.

He told her to lie quiet; he encouraged her to hope for immediate succour; and then, with much personal exertion, and at immense risk to himself, he reached the ledge of rock on which she lay, and then he supported her until the brothers had gone to a neighbouring house, which, bye-the-bye, was two good English miles off, and got assistance.

There came on, while they were gone, a terrific storm, and Flora felt that but for him who was with her she must have been hurled from the rock, and perished in an abyss below, which was almost too deep for observation.

Suffice it to say that she was rescued; and he who had, by his intrepidity, done so much towards saving her, was loaded with the most sincere and heartfelt acknowledgments by the brothers as well as by herself.

He frankly told them that his name was Holland; that he was travelling for amusement and instruction, and was by profession an artist.

He travelled with them for some time; and it was not at all to be wondered at, under the circumstances, that an attachment of the tenderest nature should spring up between him and the beautiful girl, who felt that she owed to him her life.

Mutual glances of affection were exchanged between them, and it was arranged that when he returned to England, he should come at once as an honoured guest to the house of the family of the Bannerworths.

All this was settled satisfactorily with the full knowledge and acquiescence of the two brothers, who had taken a strange attachment to the young Charles Holland, who was indeed in every way likely to propitiate the good opinion of all who knew him.

Henry explained to him exactly how they were situated, and told him that when he came he would find a welcome from all, except possibly his father, whose wayward temper he could not answer for.

Young Holland stated that he was compelled to be away for a term of two years, from certain family arrangements he had entered into, and that then he would return and hope to meet Flora unchanged as he should be.

It happened that this was the last of the continental excursions of the Bannerworths, for, before another year rolled round, the generous relative who had supplied them with the means of making such delightful trips was no more; and, likewise, the death of the father had occurred in the manner we have related, so that there was no chance as had been anticipated and hoped for by Flora, of meeting Charles Holland on the continent again, before his two years of absence from England should be expired.

Such, however, being the state of things, Flora felt reluctant to give up the house, where he would be sure to come to look for her, and her happiness was too dear to Henry to induce him to make any sacrifice of it to expediency.

Therefore was it that Bannerworth Hall, as it was sometimes called, was retained, and fully intended to be retained at all events until after Charles Holland had made his appearance, and his advice (for he was, by the young people, considered as one of the family) taken, with regard to what was advisable to be done.

With one exception this was the state of affairs at the hall, and that exception relates to Mr. Marchdale.

He was a distant relation of Mrs. Bannerworth, and, in early life, had been sincerely and tenderly attached to her.She, however, with the want of steady reflection of a young girl, as she then was, had, as is generally the case among several admirers, chosen the very worst: that is, the man who treated her with the most indifference, and who paid her the least attention, was of course, thought the most of, and she gave her hand to him.

That man was Mr. Bannerworth.But future experience had made her thoroughly awake to her former error; and, but for the love she bore her children, who were certainly all that a mother's heart could wish, she would often have deeply regretted the infatuation which had induced her to bestow her hand in the quarter she had done so.

About a month after the decease of Mr. Bannerworth, there came one to the hall, who desired to see the widow.That one was Mr. Marchdale.

It might have been some slight tenderness towards him which had never left her, or it might be the pleasure merely of seeing one whom she had known intimately in early life, but, be that as it may, she certainly gave him a kindly welcome; and he, after consenting to remain for some time as a visitor at the hall, won the esteem of the whole family by his frank demeanour and cultivated intellect.

He had travelled much and seen much, and he had turned to good account all he had seen, so that not only was Mr. Marchdale a man of sterling sound sense, but he was a most entertaining companion.

His intimate knowledge of many things concerning which they knew little or nothing; his accurate modes of thought, and a quiet, gentlemanly demeanour, such as is rarely to be met with, combined to make him esteemed by the Bannerworths.He had a small independence of his own, and being completely alone in the world, for he had neither wife nor child, Marchdale owned that he felt a pleasure in residing with the Bannerworths.

Of course he could not, in decent terms, so far offend them as to offer to pay for his subsistence, but he took good care that they should really be no losers by having him as an inmate, a matter which he could easily arrange by little presents of one kind and another, all of which he managed should be such as were not only ornamental, but actually spared his kind entertainers some positive expense which otherwise they must have gone to.

Whether or not this amiable piece of manoeuvring was seen through by the Bannerworths it is not our purpose to inquire.If it was seen through, it could not lower him in their esteem, for it was probably just what they themselves would have felt a pleasure in doing under similar circumstances, and if they did not observe it, Mr. Marchdale would, probably, be all the better pleased.

Such then may be considered by our readers as a brief outline of the state of affairs among the Bannerworths—a state which was pregnant with changes, and which changes were now likely to be rapid and conclusive.

How far the feelings of the family towards the ancient house of their race would be altered by the appearance at it of so fearful a visitor as a vampyre, we will not stop to inquire, inasmuch as such feelings will develop themselves as we proceed.

That the visitation had produced a serious effect upon all the household was sufficiently evident, as well among the educated as among the ignorant.On the second morning, Henry received notice to quit his service from the three servants he with difficulty had contrived to keep at the hall.The reason why he received such notice he knew well enough, and therefore he did not trouble himself to argue about a superstition to which he felt now himself almost, compelled to give way; for how could he say there was no such thing as a vampyre, when he had, with his own eyes, had the most abundant evidence of the terrible fact?

He calmly paid the servants, and allowed them to leave him at once without at all entering into the matter, and, for the time being, some men were procured, who, however, came evidently with fear and trembling, and probably only took the place, on account of not being able, to procure any other.The comfort of the household was likely to be completely put an end to, and reasons now for leaving the hall appeared to be most rapidly accumulating.

CHAPTER VII.

THE VISIT TO THE VAULT OF THE BANNERWORTHS, AND ITS UNPLEASANT RESULT.—THE MYSTERY.

Henry and his brother roused Flora, and after agreeing together that it would be highly imprudent to say anything to her of the proceedings of the night, they commenced a conversation with her in encouraging and kindly accents.

"Well, Flora," said Henry, "you see you have been quite undisturbed to-night."

"I have slept long, dear Henry."

"You have, and pleasantly too, I hope."

"I have not had any dreams, and I feel much refreshed, now, and quite well again."

"Thank Heaven!"said George.

"If you will tell dear mother that I am awake, I will get up with her assistance."

The brothers left the room, and they spoke to each other of it as a favourable sign, that Flora did not object to being left alone now, as she had done on the preceding morning.

"She is fast recovering, now, George," said Henry."If we could now but persuade ourselves that all this alarm would pass away, and that we should hear no more of it, we might return to our old and comparatively happy condition."

"Let us believe, Henry, that we shall."

"And yet, George, I shall not be satisfied in my mind, until I have paid a visit."

"A visit?Where?"

"To the family vault."

"Indeed, Henry!I thought you had abandoned that idea."

"I had.I have several times abandoned it; but it comes across my mind again and again."

"I much regret it."

"Look you, George; as yet, everything that has happened has tended to confirm a belief in this most horrible of all superstitions concerning vampyres."

"It has."

"Now, my great object, George, is to endeavour to disturb such a state of things, by getting something, however slight, or of a negative character, for the mind to rest upon on the other side of the question."

"I comprehend you, Henry."

"You know that at present we are not only led to believe, almost irresistibly that we have been visited here by a vampyre but that that vampyre is our ancestor, whose portrait is on the panel of the wall of the chamber into which he contrived to make his way."

"True, most true."

"Then let us, by an examination of the family vault, George, put an end to one of the evidences.If we find, as most surely we shall, the coffin of the ancestor of ours, who seems, in dress and appearance, so horribly mixed up in this affair, we shall be at rest on that head."

"But consider how many years have elapsed."

"Yes, a great number."

"What then, do you suppose, could remain of any corpse placed in a vault so long ago?"

"Decomposition must of course have done its work, but still there must be a something to show that a corpse has so undergone the process common to all nature.Double the lapse of time surely could not obliterate all traces of that which had been."

"There is reason in that, Henry."

"Besides, the coffins are all of lead, and some of stone, so that they cannot have all gone."

"True, most true."

"If in the one which, from the inscription and the date, we discover to be that of our ancestor whom we seek, we find the evident remains of a corpse, we shall be satisfied that he has rested in his tomb in peace."

"Brother, you seem bent on this adventure," said George; "if you go, I will accompany you."

"I will not engage rashly in it, George.Before I finally decide, I will again consult with Mr. Marchdale.His opinion will weigh much with me."

"And in good time, here he comes across the garden," said George, as he looked from the window of the room in which they sat.

It was Mr. Marchdale, and the brothers warmly welcomed him as he entered the apartment.

"You have been early afoot," said Henry.

"I have," he said."The fact is, that although at your solicitation I went to bed, I could not sleep, and I went out once more to search about the spot where we had seen the—the I don't know what to call it, for I have a great dislike to naming it a vampyre."

"There is not much in a name," said George.

"In this instance there is," said Marchdale."It is a name suggestive of horror."

"Made you any discovery?"said Henry.

"None whatever."

"You saw no trace of any one?"

"Not the least."

"Well, Mr. Marchdale, George and I were talking over this projected visit to the family vault."

"Yes."

"And we agreed to suspend our judgments until we saw you, and learned your opinion."

"Which I will tell you frankly," said Mr. Marchdale, "because I know you desire it freely."

"Do so."

"It is, that you make the visit."

"Indeed."

"Yes, and for this reason.You have now, as you cannot help having, a disagreeable feeling, that you may find that one coffin is untenanted.Now, if you do find it so, you scarcely make matters worse, by an additional confirmation of what already amounts to a strong supposition, and one which is likely to grow stronger by time."

"True, most true."

"On the contrary, if you find indubitable proofs that your ancestor has slept soundly in the tomb, and gone the way of all flesh, you will find yourselves much calmer, and that an attack is made upon the train of events which at present all run one way."

"That is precisely the argument I was using to George," said Henry, "a few moments since."

"Then let us go," said George, "by all means."

"It is so decided then," said Henry.

"Let it be done with caution," replied Mr. Marchdale.

"If any one can manage it, of course we can."

"Why should it not be done secretly and at night?Of course we lose nothing by making a night visit to a vault into which daylight, I presume, cannot penetrate."

"Certainly not."

"Then let it be at night."

"But we shall surely require the concurrence of some of the church authorities."

"Nay, I do not see that," interposed Mr. Marchdale."It is the vault actually vested in and belonging to yourself you wish to visit, and, therefore, you have right to visit it in any manner or at any time that may be most suitable to yourself."

"But detection in a clandestine visit might produce unpleasant consequences."

"The church is old," said George, "and we could easily find means of getting into it.There is only one objection that I see, just now, and that is, that we leave Flora unprotected."

"We do, indeed," said Henry."I did not think of that."

"It must be put to herself, as a matter for her own consideration," said Mr. Marchdale, "if she will consider herself sufficiently safe with the company and protection of your mother only."

"It would be a pity were we not all three present at the examination of the coffin," remarked Henry.

"It would, indeed.There is ample evidence," said Mr. Marchdale, "but we must not give Flora a night of sleeplessness and uneasiness on that account, and the more particularly as we cannot well explain to her where we are going, or upon what errand."

"Certainly not."

"Let us talk to her, then, about it," said Henry."I confess I am much bent upon the plan, and fain would not forego it; neither should I like other than that we three should go together."

"If you determine, then, upon it," said Marchdale, "we will go to-night; and, from your acquaintance with the place, doubtless you will be able to decide what tools are necessary."

"There is a trap-door at the bottom of the pew," said Henry; "it is not only secured down, but it is locked likewise, and I have the key in my possession."

"Indeed!"

"Yes; immediately beneath is a short flight of stone steps, which conduct at once into the vault."

"Is it large?"

"No; about the size of a moderate chamber, and with no intricacies about it."

"There can be no difficulties, then."

"None whatever, unless we meet with actual personal interruption, which I am inclined to think is very far from likely.All we shall require will be a screwdriver, with which to remove the screws, and then something with which to wrench open the coffin."

"Those we can easily provide, along with lights," remarked Mr. Marchdale.

"I hope to Heaven that this visit to the tomb will have the effect of easing your minds, and enabling you to make a successful stand against the streaming torrent of evidence that has poured in upon us regarding this most fearful of apparitions."

"I do, indeed, hope so," added Henry; "and now I will go at once to Flora, and endeavour to convince her she is safe without us to-night."

"By-the-bye, I think," said Marchdale, "that if we can induce Mr. Chillingworth to come with us, it will be a great point gained in the investigation."

"He would," said Henry, "be able to come to an accurate decision with respect to the remains—if any—in the coffin, which we could not."

"Then have him, by all means," said George."He did not seem averse last night to go on such an adventure."

"I will ask him when he makes his visit this morning upon Flora; and should he not feel disposed to join us, I am quite sure he will keep the secret of our visit."

All this being arranged, Henry proceeded to Flora, and told her that he and George, and Mr. Marchdale wished to go out for about a couple of hours in the evening after dark, if she felt sufficiently well to feel a sense of security without them.

Flora changed colour, and slightly trembled, and then, as if ashamed of her fears, she said,—

"Go, go; I will not detain you.Surely no harm can come to me in presence of my mother."

"We shall not be gone longer than the time I mention to you," said Henry.

"Oh, I shall be quite content.Besides, am I to be kept thus in fear all my life?Surely, surely not.I ought, too, to learn to defend myself."

Henry caught at the idea, as he said,—

"If fire-arms were left you, do you think you would have courage to use them?"

"I do, Henry."

"Then you shall have them; and let me beg of you to shoot any one without the least hesitation who shall come into your chamber."

"I will, Henry.If ever human being was justified in the use of deadly weapons, I am now.Heaven protect me from a repetition of the visit to which I have now been once subjected.Rather, oh, much rather would I die a hundred deaths than suffer what I have suffered."

"Do not allow it, dear Flora, to press too heavily upon your mind in dwelling upon it in conversation.I still entertain a sanguine expectation that something may arise to afford a far less dreadful explanation of what has occurred than what you have put upon it.Be of good cheer, Flora, we shall go one hour after sunset, and return in about two hours from the time at which we leave here, you may be assured."

Notwithstanding this ready and courageous acquiescence of Flora in the arrangement, Henry was not without his apprehension that when the night should come again, her fears would return with it; but he spoke to Mr. Chillingworth upon the subject, and got that gentleman's ready consent to accompany them.

He promised to meet them at the church porch exactly at nine o'clock, and matters were all arranged, and Henry waited with much eagerness and anxiety now for the coming night, which he hoped would dissipate one of the fearful deductions which his imagination had drawn from recent circumstances.

He gave to Flora a pair of pistols of his own, upon which he knew he could depend, and he took good care to load them well, so that there could be no likelihood whatever of their missing fire at a critical moment.

"Now, Flora," he said, "I have seen you use fire-arms when you were much younger than you are now, and therefore I need give you no instructions.If any intruder does come, and you do fire, be sure you take a good aim, and shoot low."

"I will, Henry, I will; and you will be back in two hours?"

"Most assuredly I will."

The day wore on, evening came, and then deepened into night.It turned out to be a cloudy night, and therefore the moon's brilliance was nothing near equal to what it had been on the preceding night Still, however, it had sufficient power over the vapours that frequently covered it for many minutes together, to produce a considerable light effect upon the face of nature, and the night was consequently very far, indeed, from what might be called a dark one.

George, Henry, and Marchdale, met in one of the lower rooms of the house, previous to starting upon their expedition; and after satisfying themselves that they had with them all the tools that were necessary, inclusive of the same small, but well-tempered iron crow-bar with which Marchdale had, on the night of the visit of the vampyre, forced open the door of Flora's chamber, they left the hall, and proceeded at a rapid pace towards the church.

"And Flora does not seem much alarmed," said Marchdale, "at being left alone?"

"No," replied Henry, "she has made up her mind with a strong natural courage which I knew was in her disposition to resist as much as possible the depressing effects of the awful visitation she has endured."

"It would have driven some really mad."

"It would, indeed; and her own reason tottered on its throne, but, thank Heaven, she has recovered."

"And I fervently hope that, through her life," added Marchdale, "she may never have such another trial."

"We will not for a moment believe that such a thing can occur twice."

"She is one among a thousand.Most young girls would never at all have recovered the fearful shock to the nerves."

"Not only has she recovered," said Henry, "but a spirit, which I am rejoiced to see, because it is one which will uphold her, of resistance now possesses her."

"Yes, she actually—I forgot to tell you before—but she actually asked me for arms to resist any second visitation."

"You much surprise me."

"Yes, I was surprised, as well as pleased, myself."

"I would have left her one of my pistols had I been aware of her having made such a request.Do you know if she can use fire-arms?"

"Oh, yes; well."

"What a pity.I have them both with me."

"Oh, she is provided."

"Provided?"

"Yes; I found some pistols which I used to take with me on the continent, and she has them both well loaded, so that if the vampyre makes his appearance, he is likely to meet with rather a warm reception."

"Good God!was it not dangerous?"

"Not at all, I think."

"Well, you know best, certainly, of course.I hope the vampyre may come, and that we may have the pleasure, when we return, of finding him dead.By-the-bye, I—I—.Bless me, I have forgot to get the materials for lights, which I pledged myself to do."

"How unfortunate."

"Walk on slowly, while I run back and get them."

"Oh, we are too far—"

"Hilloa!"cried a man at this moment, some distance in front of them.

"It is Mr. Chillingworth," said Henry.

"Hilloa," cried the worthy doctor again."Is that you, my friend, Henry Bannerworth?"

"It is," cried Henry.

Mr. Chillingworth now came up to them and said,—

"I was before my time, so rather than wait at the church porch, which would have exposed me to observation perhaps, I thought it better to walk on, and chance meeting with you."

"You guessed we should come this way?'

"Yes, and so it turns out, really.It is unquestionably your most direct route to the church."

"I think I will go back," said Mr Marchdale.

"Back!"exclaimed the doctor; "what for?"

"I forgot the means of getting lights.We have candles, but no means of lighting them."

"Make yourselves easy on that score," said Mr. Chillingworth."I am never without some chemical matches of my own manufacture, so that as you have the candles, that can be no bar to our going on a once."

"That is fortunate," said Henry.

"Very," added Marchdale; "for it seems a mile's hard walking for me, or at least half a mile from the hall.Let us now push on."

They did push on, all four walking at a brisk pace.The church, although it belonged to the village, was not in it.On the contrary, it was situated at the end of a long lane, which was a mile nearly from the village, in the direction of the hall, therefore, in going to it from the hall, that amount of distance was saved, although it was always called and considered the village church.

It stood alone, with the exception of a glebe house and two cottages, that were occupied by persons who held situations about the sacred edifice, and who were supposed, being on the spot, to keep watch and ward over it.

It was an ancient building of the early English style of architecture, or rather Norman, with one of those antique, square, short towers, built of flint stones firmly embedded in cement, which, from time, had acquired almost the consistency of stone itself.There were numerous arched windows, partaking something of the more florid gothic style, although scarcely ornamental enough to be called such.The edifice stood in the centre of a grave-yard, which extended over a space of about half an acre, and altogether it was one of the prettiest and most rural old churches within many miles of the spot.

Many a lover of the antique and of the picturesque, for it was both, went out of his way while travelling in the neighbourhood to look at it, and it had an extensive and well-deserved reputation as a fine specimen of its class and style of building.

In Kent, to the present day, are some fine specimens of the old Roman style of church, building; and, although they are as rapidly pulled down as the abuse of modern architects, and the cupidity of speculators, and the vanity of clergymen can possibly encourage, in older to erect flimsy, Italianised structures in their stead, yet sufficient of them remain dotted over England to interest the traveller.At Walesden there is a church of this description which will well repay a visit.This, then, was the kind of building into which it was the intention of our four friends to penetrate, not on an unholy, or an unjustifiable errand, but on one which, proceeding from good and proper motives, it was highly desirable to conduct in as secret a manner as possible.

The moon was more densely covered by clouds than it had yet been that evening, when they reached the little wicket-gate which led into the churchyard, through which was a regularly used thoroughfare.

"We have a favourable night," remarked Henry, "for we are not so likely to be disturbed."

"And now, the question is, how are we to get in?"said Mr. Chillingworth, as he paused, and glanced up at the ancient building.

"The doors," said George, "would effectually resist us."

"How can it be done, then?"

"The only way I can think of," said Henry, "is to get out one of the small diamond-shaped panes of glass from one of the low windows, and then we can one of us put in our hands, and undo the fastening, which is very simple, when the window opens like a door, and it is but a step into the church."

"A good way," said Marchdale."We will lose no time."

They walked round the church till they came to a very low window indeed, near to an angle of the wall, where a huge abutment struck far out into the burial-ground.

"Will you do it, Henry?"said George.

"Yes.I have often noticed the fastenings.Just give me a slight hoist up, and all will be right."

George did so, and Henry with his knife easily bent back some of the leadwork which held in one of the panes of glass, and then got it out whole.He handed it down to George, saying,—

"Take this, George.We can easily replace it when we leave, so that there can be no signs left of any one having been here at all."

George took the piece of thick, dim-coloured glass, and in another moment Henry had succeeded in opening the window, and the mode of ingress to the old church was fair and easy before them all, had there been ever so many.

"I wonder," said Marchdale, "that a place so inefficiently protected has never been robbed."

"No wonder at all," remarked Mr. Chillingworth."There is nothing to take that I am aware of that would repay anybody the trouble of taking."

"Indeed!"

"Not an article.The pulpit, to be sure, is covered with faded velvet; but beyond that, and an old box, in which I believe nothing is left but some books, I think there is no temptation."

"And that, Heaven knows, is little enough, then."

"Come on," said Henry."Be careful; there is nothing beneath the window, and the depth is about two feet."

Thus guided, they all got fairly into the sacred edifice, and then Henry closed the window, and fastened it on the inside as he said,—

"We have nothing to do now but to set to work opening a way into the vault, and I trust that Heaven will pardon me for thus desecrating the tomb of my ancestors, from a consideration of the object I have in view by so doing."

"It does seem wrong thus to tamper with the secrets of the tomb," remarked Mr. Marchdale.

"The secrets of a fiddlestick!"said the doctor."What secrets has the tomb I wonder?"

"Well, but, my dear sir—"

"Nay, my dear sir, it is high time that death, which is, then, the inevitable fate of us all, should be regarded with more philosophic eyes than it is.There are no secrets in the tomb but such as may well be endeavoured to be kept secret."

"What do you mean?"

"There is one which very probably we shall find unpleasantly revealed."

"Which is that?"

"The not over pleasant odour of decomposed animal remains—beyond that I know of nothing of a secret nature that the tomb can show us."

"Ah, your profession hardens you to such matters."

"And a very good thing that it does, or else, if all men were to look upon a dead body as something almost too dreadful to look upon, and by far too horrible to touch, surgery would lose its value, and crime, in many instances of the most obnoxious character, would go unpunished."

"If we have a light here," said Henry, "we shall run the greatest chance in the world of being seen, for the church has many windows."

"Do not have one, then, by any means," said Mr. Chillingworth."A match held low down in the pew may enable us to open the vault."

"That will be the only plan."

Henry led them to the pew which belonged to his family, and in the floor of which was the trap door.

"When was it last opened?"inquired Marchdale.

"When my father died," said Henry; "some ten months ago now, I should think."

"The screws, then, have had ample time to fix themselves with fresh rust."

"Here is one of my chemical matches," said Mr. Chillingworth, as he suddenly irradiated the pew with a clear and beautiful flame, that lasted about a minute.

The heads of the screws were easily discernible, and the short time that the light lasted had enabled Henry to turn the key he had brought with him in the lock.

"I think that without a light now," he said, "I can turn the screws well."

"Can you?"

"Yes; there are but four."

"Try it, then."

Henry did so, and from the screws having very large heads, and being made purposely, for the convenience of removal when required, with deep indentations to receive the screw-driver, he found no difficulty in feeling for the proper places, and extracting the screws without any more light than was afforded to him from the general whitish aspect of the heavens.

"Now, Mr. Chillingworth," he said "another of your matches, if you please.I have all the screws so loose that I can pick them up with my fingers."

"Here," said the doctor.

In another moment the pew was as light as day, and Henry succeeded in taking out the few screws, which he placed in his pocket for their greater security, since, of course, the intention was to replace everything exactly as it was found, in order that not the least surmise should arise in the mind of any person that the vault had been opened, and visited for any purpose whatever, secretly or otherwise.

"Let us descend," said Henry."There is no further obstacle, my friends.Let us descend."

"If any one," remarked George, in a whisper, as they slowly descended the stairs which conducted into the vault—"if any one had told me that I should be descending into a vault for the purpose of ascertaining if a dead body, which had been nearly a century there, was removed or not, and had become a vampyre, I should have denounced the idea as one of the most absurd that ever entered the brain of a human being."

"We are the very slaves of circumstances," said Marchdale, "and we never know what we may do, or what we may not.What appears to us so improbable as to border even upon the impossible at one time, is at another the only course of action which appears feasibly open to us to attempt to pursue."

They had now reached the vault, the floor of which was composed of flat red tiles, laid in tolerable order the one beside the other.As Henry had stated, the vault was by no means of large extent.Indeed, several of the apartments for the living, at the hall, were much larger than was that one destined for the dead.

The atmosphere was dump and noisome, but not by any means so bad as might have been expected, considering the number of months which had elapsed since last the vault was opened to receive one of its ghastly and still visitants.

"Now for one of your lights.Mr. Chillingworth.You say you have the candles, I think, Marchdale, although you forgot the matches."

"I have.They are here."

Marchdale took from his pocket a parcel which contained several wax candles, and when it was opened, a smaller packet fell to the ground.

"Why, these are instantaneous matches," said Mr. Chillingworth, as he lifted the small packet up.

"They are; and what a fruitless journey I should have had back to the hall," said Mr. Marchdale, "if you had not been so well provided as you are with the means of getting a light.These matches, which I thought I had not with me, have been, in the hurry of departure, enclosed, you see, with the candles.Truly, I should have hunted for them at home in vain."

Mr. Chillingworth lit the wax candle which was now handed to him by Marchdale, and in another moment the vault from one end of it to the other was quite clearly discernible.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE COFFIN.—THE ABSENCE OF THE DEAD.—THE MYSTERIOUS CIRCUMSTANCE, AND THE CONSTERNATION OF GEORGE.

They were all silent for a few moments as they looked around them with natural feelings of curiosity.Two of that party had of course never been in that vault at all, and the brothers, although they had descended into it upon the occasion, nearly a year before, of their father being placed in it, still looked upon it with almost as curious eyes as they who now had their first sight of it.

If a man be at all of a thoughtful or imaginative cast of mind, some curious sensations are sure to come over him, upon standing in such a place, where he knows around him lie, in the calmness of death, those in whose veins have flowed kindred blood to him—who bore the same name, and who preceded him in the brief drama of his existence, influencing his destiny and his position in life probably largely by their actions compounded of their virtues and their vices.

Henry Bannerworth and his brother George were just the kind of persons to feel strongly such sensations.Both were reflective, imaginative, educated young men, and, as the light from the wax candle flashed upon their faces, it was evident how deeply they felt the situation in which they were placed.

Mr. Chillingworth and Marchdale were silent.They both knew what was passing in the minds of the brothers, and they had too much delicacy to interrupt a train of thought which, although from having no affinity with the dead who lay around, they could not share in, yet they respected.Henry at length, with a sudden start, seemed to recover himself from his reverie.

"This is a time for action, George," he said, "and not for romantic thought.Let us proceed."

"Yes, yes," said George, and he advanced a step towards the centre of the vault.

"Can you find out among all these coffins, for there seem to be nearly twenty," said Mr. Chillingworth, "which is the one we seek?"

"I think we may," replied Henry."Some of the earlier coffins of our race, I know, were made of marble, and others of metal, both of which materials, I expect, would withstand the encroaches of time for a hundred years, at least."

"Let us examine," said George.

There were shelves or niches built into the walls all round, on which the coffins were placed, so that there could not be much difficulty in a minute examination of them all, the one after the other.

When, however, they came to look, they found that "decay's offensive fingers" had been more busy than they could have imagined, and that whatever they touched of the earlier coffins crumbled into dust before their very fingers.

In some cases the inscriptions were quite illegible, and, in others, the plates that had borne them had fallen on to the floor of the vault, so that it was impossible to say to which coffin they belonged.

Of course, the more recent and fresh-looking coffins they did not examine, because they could not have anything to do with the object of that melancholy visit.

"We shall arrive at no conclusion," said George."All seems to have rotted away among those coffins where we might expect to find the one belonging to Marmaduke Bannerworth, our ancestor."

"Here is a coffin plate," said Marchdale, taking one from the floor.

He handed it to Mr. Chillingworth, who, upon an inspection of it, close to the light, exclaimed,—

"It must have belonged to the coffin you seek."

"What says it?"

"Ye mortale remains of Marmaduke Bannerworth, Yeoman.God reste his soule.A.D.1540."

"It is the plate belonging to his coffin," said Henry, "and now our search is fruitless."

"It is so, indeed," exclaimed George, "for how can we tell to which of the coffins that have lost the plates this one really belongs?"

"I should not be so hopeless," said Marchdale."I have, from time to time, in the pursuit of antiquarian lore, which I was once fond of, entered many vaults, and I have always observed that an inner coffin of metal was sound and good, while the outer one of wood had rotted away, and yielded at once to the touch of the first hand that was laid upon it."

"But, admitting that to be the case," said Henry, "how does that assist us in the identification of a coffin?"

"I have always, in my experience, found the name and rank of the deceased engraved upon the lid of the inner coffin, as well as being set forth in a much more perishable manner on the plate which was secured to the outer one."

"He is right," said Mr. Chillingworth."I wonder we never thought of that.If your ancestor was buried in a leaden coffin, there will be no difficulty in finding which it is."

Henry seized the light, and proceeding to one of the coffins, which seemed to be a mass of decay, he pulled away some of the rotted wood work, and then suddenly exclaimed,—

"You are quite right.Here is a firm strong leaden coffin within, which, although quite black, does not otherwise appear to have suffered."

"What is the inscription on that?"said George.

With difficulty the name on the lid was deciphered, but it was found not to be the coffin of him whom they sought.

"We can make short work of this," said Marchdale, "by only examining those leaden coffins which have lost the plates from off their outer cases.There do not appear to be many in such a state."

He then, with another light, which he lighted from the one that Henry now carried, commenced actively assisting in the search, which was carried on silently for more than ten minutes.

Suddenly Mr. Marchdale cried, in a tone of excitement,—

"I have found it.It is here."

They all immediately surrounded the spot where he was, and then he pointed to the lid of a coffin, which he had been rubbing with his handkerchief, in order to make the inscription more legible, and said,—

"See.It is here."

By the combined light of the candles they saw the words,—

"Marmaduke Bannerworth, Yeoman, 1640."

"Yes, there can be no mistake here," said Henry."This is the coffin, and it shall be opened."

"I have the iron crowbar here," said Marchdale."It is an old friend of mine, and I am accustomed to the use of it.Shall I open the coffin?"

"Do so—do so," said Henry.

They stood around in silence, while Mr. Marchdale, with much care, proceeded to open the coffin, which seemed of great thickness, and was of solid lead.

It was probably the partial rotting of the metal, in consequence of the damps of that place, that made it easier to open the coffin than it otherwise would have been, but certain it was that the top came away remarkably easily.Indeed, so easily did it come off, that another supposition might have been hazarded, namely, that it had never at all been effectually fastened.

The few moments that elapsed were ones of very great suspense to every one there present; and it would, indeed, be quite sure to assert, that all the world was for the time forgotten in the absorbing interest which appertained to the affair which was in progress.

The candles were now both held by Mr. Chillingworth, and they were so held as to cast a full and clear light upon the coffin.Now the lid slid off, and Henry eagerly gazed into the interior.

There lay something certainly there, and an audible "Thank God!"escaped his lips.

"The body is there!"exclaimed George.

"All right," said Marchdale, "here it is.There is something, and what else can it be?"

"Hold the lights," said Mr. Chillingworth; "hold the lights, some of you; let us be quite certain."

George took the lights, and Mr. Chillingworth, without any hesitation, dipped his hands at once into the coffin, and took up some fragments of rags which were there.They were so rotten, that they fell to pieces in his grasp, like so many pieces of tinder.

There was a death-like pause for some few moments, and then Mr. Chillingworth said, in a low voice,—

"There is not the least vestige of a dead body here."

Henry gave a deep groan, as he said,—

"Mr. Chillingworth, can you take upon yourself to say that no corpse has undergone the process of decomposition in this coffin?"

"To answer your question exactly, as probably in your hurry you have worded it," said Mr. Chillingworth, "I cannot take upon myself to say any such thing; but this I can say, namely, that in this coffin there are no animal remains, and that it is quite impossible that any corpse enclosed here could, in any lapse of time, have so utterly and entirely disappeared."

"I am answered," said Henry.

"Good God!"exclaimed George, "and has this but added another damning proof, to those we have already on our minds, of one of the must dreadful superstitions that ever the mind of man conceived?"

"It would seem so," said Marchdale, sadly.

"Oh, that I were dead!This is terrible.God of heaven, why are these things?Oh, if I were but dead, and so spared the torture of supposing such things possible."

"Think again, Mr. Chillingworth; I pray you think again," cried Marchdale.

"If I were to think for the remainder of my existence," he replied, "I could come to no other conclusion.It is not a matter of opinion; it is a matter of fact."

"You are positive, then," said Henry, "that the dead body of Marmaduke Bannerworth is not rested here?"

"I am positive.Look for yourselves.The lead is but slightly discoloured; it looks tolerably clean and fresh; there is not a vestige of putrefaction—no bones, no dust even."

They did all look for themselves, and the most casual glance was sufficient to satisfy the most sceptical.

"All is over," said Henry; "let us now leave this place; and all I can now ask of you, my friends, is to lock this dreadful secret deep in your own hearts."

"It shall never pass my lips," said Marchdale.

"Nor mine, you may depend," said the doctor."I was much in hopes that this night's work would have had the effect of dissipating, instead of adding to, the gloomy fancies that now possess you."

"Good heavens!"cried George, "can you call them fancies, Mr. Chillingworth?"

"I do, indeed."

"Have you yet a doubt?"

"My young friend, I told you from the first, that I would not believe in your vampyre; and I tell you now, that if one was to come and lay hold of me by the throat, as long as I could at all gasp for breath I would tell him he was a d——d impostor."

"This is carrying incredulity to the verge of obstinacy."

"Far beyond it, if you please."

"You will not be convinced?"said Marchdale.

"I most decidedly, on this point, will not."

"Then you are one who would doubt a miracle, if you saw it with your own eyes."

"I would, because I do not believe in miracles.I should endeavour to find some rational and some scientific means of accounting for the phenomenon, and that's the very reason why we have no miracles now-a-days, between you and I, and no prophets and saints, and all that sort of thing."

"I would rather avoid such observations in such a place as this," said Marchdale.

"Nay, do not be the moral coward," cried Mr. Chillingworth, "to make your opinions, or the expression of them, dependent upon any certain locality."

"I know not what to think," said Henry; "I am bewildered quite.Let us now come away."

Mr. Marchdale replaced the lid of the coffin, and then the little party moved towards the staircase.Henry turned before he ascended, and glanced back into the vault.

"Oh," he said, "if I could but think there had been some mistake, some error of judgment, on which the mind could rest for hope."

"I deeply regret," said Marchdale, "that I so strenuously advised this expedition.I did hope that from it would have resulted much good."

"And you had every reason so to hope," said Chillingworth."I advised it likewise, and I tell you that its result perfectly astonishes me, although I will not allow myself to embrace at once all the conclusions to which it would seem to lead me."

"I am satisfied," said Henry; "I know you both advised me for the best.The curse of Heaven seems now to have fallen upon me and my house."

"Oh, nonsense!"said Chillingworth."What for?"

"Alas!I know not."

"Then you may depend that Heaven would never act so oddly.In the first place, Heaven don't curse anybody; and, in the second, it is too just to inflict pain where pain is not amply deserved."

They ascended the gloomy staircase of the vault.The countenances of both George and Henry were very much saddened, and it was quite evident that their thoughts were by far too busy to enable them to enter into any conversation.They did not, and particularly George, seem to hear all that was said to them.Their intellects seemed almost stunned by the unexpected circumstance of the disappearance of the body of their ancestor.

All along they had, although almost unknown to themselves, felt a sort of conviction that they must find some remains of Marmaduke Bannerworth, which would render the supposition, even in the most superstitious minds, that he was the vampyre, a thing totally and physically impossible.

But now the whole question assumed a far more bewildering shape.The body was not in its coffin—it had not there quietly slept the long sleep of death common to humanity.Where was it then?What had become of it?Where, how, and under what circumstances had it been removed?Had it itself burst the bands that held it, and hideously stalked forth into the world again to make one of its seeming inhabitants, and kept up for a hundred years a dreadful existence by such adventures as it had consummated at the hall, where, in the course of ordinary human life, it had once lived?

All these were questions which irresistibly pressed themselves upon the consideration of Henry and his brother.They were awful questions.

And yet, take any sober, sane, thinking, educated man, and show him all that they had seen, subject him to all to which they had been subjected, and say if human reason, and all the arguments that the subtlest brain could back it with, would be able to hold out against such a vast accumulation of horrible evidences, and say—"I don't believe it."

Mr. Chillingworth's was the only plan.He would not argue the question.He said at once,—

"I will not believe this thing—upon this point I will yield to no evidence whatever."

That was the only way of disposing of such a question; but there are not many who could so dispose of it, and not one so much interested in it as were the brothers Bannerworth, who could at all hope to get into such a state of mind.

The boards were laid carefully down again, and the screws replaced.Henry found himself unequal to the task, so it was done by Marchdale, who took pains to replace everything in the same state in which they had found it, even to the laying even the matting at the bottom of the pew.

Then they extinguished the light, and, with heavy hearts, they all walked towards the window, to leave the sacred edifice by the same means they had entered it.

"Shall we replace the pane of glass?"said Marchdale.

"Oh, it matters not—it matters not," said Henry, listlessly; "nothing matters now.I care not what becomes of me—I am getting weary of a life which now must be one of misery and dread."

"You must not allow yourself to fall into such a state of mind as this," said the doctor, "or you will become a patient of mine very quickly."

"I cannot help it."

"Well, but be a man.If there are serious evils affecting you, fight out against them the best way you can."

"I cannot."

"Come, now, listen to me.We need not, I think, trouble ourselves about the pane of glass, so come along."

He took the arm of Henry and walked on with him a little in advance of the others.

"Henry," he said, "the best way, you may depend, of meeting evils, be they great or small, is to get up an obstinate feeling of defiance against them.Now, when anything occurs which is uncomfortable to me, I endeavour to convince myself, and I have no great difficulty in doing so, that I am a decidedly injured man."

"Indeed!"

"Yes; I get very angry, and that gets up a kind of obstinacy, which makes me not feel half so much mental misery as would be my portion, if I were to succumb to the evil, and commence whining over it, as many people do, under the pretence of being resigned."

"But this family affliction of mine transcends anything that anybody else ever endured."

"I don't know that; but it is a view of the subject which, if I were you, would only make me more obstinate."

"What can I do?"

"In the first place, I would say to myself, 'There may or there may not be supernatural beings, who, from some physical derangement of the ordinary nature of things, make themselves obnoxious to living people; if there are, d—n them!There may be vampyres; and if there are, I defy them.'Let the imagination paint its very worst terrors; let fear do what it will and what it can in peopling the mind with horrors.Shrink from nothing, and even then I would defy them all."

"Is not that like defying Heaven?"

"Most certainly not; for in all we say and in all we do we act from the impulses of that mind which is given to us by Heaven itself.If Heaven creates an intellect and a mind of a certain order, Heaven will not quarrel that it does the work which it was adapted to do."

"I know these are your opinions.I have heard you mention them before."

"They are the opinions of every rational person.Henry Bannerworth, because they will stand the test of reason; and what I urge upon you is, not to allow yourself to be mentally prostrated, even if a vampyre has paid a visit to your house.Defy him, say I—fight him.Self-preservation is a great law of nature, implanted in all our hearts; do you summon it to your aid."

"I will endeavour to think as you would have me.I thought more than once of summoning religion to my aid."

"Well, that is religion."

"Indeed!"

"I consider so, and the most rational religion of all.All that we read about religion that does not seem expressly to agree with it, you may consider as an allegory."

"But, Mr. Chillingworth, I cannot and will not renounce the sublime truths of Scripture.They may be incomprehensible; they may be inconsistent; and some of them may look ridiculous; but still they are sacred and sublime, and I will not renounce them although my reason may not accord with them, because they are the laws of Heaven."

No wonder this powerful argument silenced Mr. Chillingworth, who was one of those characters in society who hold most dreadful opinions, and who would destroy religious beliefs, and all the different sects in the world, if they could, and endeavour to introduce instead some horrible system of human reason and profound philosophy.

But how soon the religious man silences his opponent; and let it not be supposed that, because his opponent says no more upon the subject, he does so because he is disgusted with the stupidity of the other; no, it is because he is completely beaten, and has nothing more to say.

The distance now between the church and the hall was nearly traversed, and Mr. Chillingworth, who was a very good man, notwithstanding his disbelief in certain things of course paved the way for him to hell, took a kind leave of Mr. Marchdale and the brothers, promising to call on the following morning and see Flora.

Henry and George then, in earnest conversation with Marchdale, proceeded homewards.It was evident that the scene in the vault had made a deep and saddening impression upon them, and one which was not likely easily to be eradicated.

CHAPTER IX.

THE OCCURRENCES OF THE NIGHT AT THE HALL.—THE SECOND APPEARANCE OF THE VAMPYRE, AND THE PISTOL-SHOT.

Despite the full and free consent which Flora had given to her brothers to entrust her solely to the care of her mother and her own courage at the hall, she felt greater fear creep over her after they were gone than she chose to acknowledge.

A sort of presentiment appeared to come over her that some evil was about to occur, and more than once she caught herself almost in the act of saying,—

"I wish they had not gone."

Mrs. Bannerworth, too, could not be supposed to be entirely destitute of uncomfortable feelings, when she came to consider how poor a guard she was over her beautiful child, and how much terror might even deprive of the little power she had, should the dreadful visitor again make his appearance.

"But it is but for two hours," thought Flora, "and two hours will soon pass away."

There was, too, another feeling which gave her some degree of confidence, although it arose from a bad source, inasmuch as it was one which showed powerfully how much her mind was dwelling on the particulars of the horrible belief in the class of supernatural beings, one of whom she believed had visited her.

That consideration was this.The two hours of absence from the hall of its male inhabitants, would be from nine o'clock until eleven, and those were not the two hours during which she felt that she would be most timid on account of the vampyre.

"It was after midnight before," she thought, "when it came, and perhaps it may not be able to come earlier.It may not have the power, until that time, to make its hideous visits, and, therefore, I will believe myself safe."

She had made up her mind not to go to bed until the return of her brothers, and she and her mother sat in a small room that was used as a breakfast-room, and which had a latticed window that opened on to the lawn.

This window had in the inside strong oaken shutters, which had been fastened as securely as their construction would admit of some time before the departure of the brothers and Mr. Marchdale on that melancholy expedition, the object of which, if it had been known to her, would have added so much to the terrors of poor Flora.

It was not even guessed at, however remotely, so that she had not the additional affliction of thinking, that while she was sitting there, a prey to all sorts of imaginative terrors, they were perhaps gathering fresh evidence, as, indeed, they were, of the dreadful reality of the appearance which, but for the collateral circumstances attendant upon its coming and its going, she would fain have persuaded herself was but the vision of a dream.

It was before nine that the brothers started, but in her own mind Flora gave them to eleven, and when she heard ten o'clock sound from a clock which stood in the hall, she felt pleased to think that in another hour they would surely be at home.

"My dear," said her mother, "you look more like yourself, now."

"Do, I, mother?"

"Yes, you are well again."

"Ah, if I could forget—"

"Time, my dear Flora, will enable you to do so, and all the fear of what made you so unwell will pass away.You will soon forget it all."

"I will hope to do so."

"Be assured that, some day or another, something will occur, as Henry says, to explain all that has happened, in some way consistent with reason and the ordinary nature of things, my dear Flora."

"Oh, I will cling to such a belief; I will get Henry, upon whose judgment I know I can rely, to tell me so, and each time that I hear such words from his lips, I will contrive to dismiss some portion of the terror which now, I cannot but confess, clings to my heart."

Flora laid her hand upon her mother's arm, and in a low, anxious tone of voice, said,—"Listen, mother."

Mrs. Bannerworth turned pale, as she said,—"Listen to what, dear?"

"Within these last ten minutes," said Flora, "I have thought three or four times that I heard a slight noise without.Nay, mother, do not tremble—it may be only fancy."

Flora herself trembled, and was of a death-like paleness; once or twice she passed her hand across her brow, and altogether she presented a picture of much mental suffering.

They now conversed in anxious whispers, and almost all they said consisted in anxious wishes for the return of the brothers and Mr. Marchdale.

"You will be happier and more assured, my dear, with some company," said Mrs. Bannerworth."Shall I ring for the servants, and let them remain in the room with us, until they who are our best safeguards next to Heaven return?"

"Hush—hush—hush, mother!"

"What do you hear?"

"I thought—I heard a faint sound."

"I heard nothing, dear."

"Listen again, mother.Surely I could not be deceived so often.I have now, at least, six times heard a sound as if some one was outside by the windows."

"No, no, my darling, do not think; your imagination is active and in a state of excitement."

"It is, and yet—"

"Believe me, it deceives you."

"I hope to Heaven it does!"

There was a pause of some minutes' duration, and then Mrs. Bannerworth again urged slightly the calling of some of the servants, for she thought that their presence might have the effect of giving a different direction to her child's thoughts; but Flora saw her place her hand upon the bell, and she said,—

"No, mother, no—not yet, not yet.Perhaps I am deceived."

Mrs. Bannerworth upon this sat down, but no sooner had she done so than she heartily regretted she had not rung the bell, for, before, another word could be spoken, there came too perceptibly upon their ears for there to be any mistake at all about it, a strange scratching noise upon the window outside.

A faint cry came from Flora's lips, as she exclaimed, in a voice of great agony,—

"Oh, God!—oh, God!It has come again!"

Mrs. Bannerworth became faint, and unable to move or speak at all; she could only sit like one paralysed, and unable to do more than listen to and see what was going on.

The scratching noise continued for a few seconds, and then altogether ceased.Perhaps, under ordinary circumstances, such a sound outside the window would have scarcely afforded food for comment at all, or, if it had, it would have been attributed to some natural effect, or to the exertions of some bird or animal to obtain admittance to the house.

But there had occurred now enough in that family to make any little sound of wonderful importance, and these things which before would have passed completely unheeded, at all events without creating much alarm, were now invested with a fearful interest.

When the scratching noise ceased, Flora spoke in a low, anxious whisper, as she said,—

"Mother, you heard it then?"

Mrs. Bannerworth tried to speak, but she could not; and then suddenly, with a loud clash, the bar, which on the inside appeared to fasten the shutters strongly, fell as if by some invisible agency, and the shutters now, but for the intervention of the window, could be easily pushed open from without.

Mrs. Bannerworth covered her face with her hands, and, after rocking to and fro for a moment, she fell off her chair, having fainted with the excess of terror that came over her.

For about the space of time in which a fast speaker could count twelve, Flora thought her reason was leaving her, but it did not.She found herself recovering; and there she sat, with her eyes fixed upon the window, looking more like some exquisitely-chiselled statue of despair than a being of flesh and blood, expecting each moment to have its eyes blasted by some horrible appearance, such as might be supposed to drive her to madness.

And now again came the strange knocking or scratching against the glass of the window.

This continued for some minutes, during which it appeared likewise to Flora that some confusion was going on at another part of the house, for she fancied she heard voices and the banging of doors.

It seemed to her as if she must have sat looking at the shutters of that window a long time before she saw them shake, and then one wide hinged portion of them slowly opened.

Once again horror appeared to be on the point of producing madness in her brain, and then, as before, a feeling of calmness rapidly ensued.

She was able to see plainly that something was by the window, but what it was she could not plainly discern, in consequence of the lights she had in the room.A few moments, however, sufficed to settle that mystery, for the window was opened and a figure stood before her.

One glance, one terrified glance, in which her whole soul was concentrated, sufficed to shew her who and what the figure was.There was the tall, gaunt form—there was the faded ancient apparel—the lustrous metallic-looking eyes—its half-opened month, exhibiting the tusk-like teeth!It was—yes, it was—the vampyre!

It stood for a moment gazing at her, and then in the hideous way it had attempted before to speak, it apparently endeavoured to utter some words which it could not make articulate to human ears.The pistols lay before Flora.Mechanically she raised one, and pointed it at the figure.It advanced a step, and then she pulled the trigger.

A stunning report followed.There was a loud cry of pain, and the vampyre fled.The smoke and the confusion that was incidental to the spot prevented her from seeing if the figure walked or ran away.She thought she heard a crashing sound among the plants outside the window, as if it had fallen, but she did not feel quite sure.

It was no effort of any reflection, but a purely mechanical movement, that made her raise the other pistol, and discharge that likewise in the direction the vampyre had taken.Then casting the weapon away, she rose, and made a frantic rush from the room.She opened the door, and was dashing out, when she found herself caught in the circling arms of some one who either had been there waiting, or who had just at that moment got there.

The thought that it was the vampyre, who by some mysterious means, had got there, and was about to make her his prey, now overcame her completely, and she sunk into a state of utter insensibility on the moment.

CHAPTER X.

THE RETURN FROM THE VAULT.—THE ALARM, AND THE SEARCH AROUND THE HALL.

It so happened that George and Henry Bannerworth, along with Mr. Marchdale, had just reached the gate which conducted into the garden of the mansion when they all were alarmed by the report of a pistol.Amid the stillness of the night, it came upon them with so sudden a shock, that they involuntarily paused, and there came from the lips of each an expression of alarm.

"Good heavens!"cried George, "can that be Flora firing at any intruder?"

"It must be," cried Henry; "she has in her possession the only weapons in the house."

Mr. Marchdale turned very pale, and trembled slightly, but he did not speak.

"On, on," cried Henry; "for God's sake, let us hasten on."

As he spoke, he cleared the gate at a bound, and at a terrific pace he made towards the house, passing over beds, and plantations, and flowers heedlessly, so that he went the most direct way to it.

Before, however, it was possible for any human speed to accomplish even half of the distance, the report of the other shot came upon his ears, and he even fancied he heard the bullet whistle past his head in tolerably close proximity.This supposition gave him a clue to the direction at all events from whence the shots proceeded, otherwise he knew not from which window they were fired, because it had not occurred to him, previous to leaving home, to inquire in which room Flora and his mother were likely to be seated waiting his return.

He was right as regarded the bullet.It was that winged messenger of death which had passed his head in such very dangerous proximity, and consequently he made with tolerable accuracy towards the open window from whence the shots had been fired.

The night was not near so dark as it had been, although even yet it was very far from being a light one, and he was soon enabled to see that there was a room, the window of which was wide open, and lights burning on the table within.He made towards it in a moment, and entered it.To his astonishment, the first objects he beheld were Flora and a stranger, who was now supporting her in his arms. To grapple him by the throat was the work of a moment, but the stranger cried aloud in a voice which sounded familiar to Harry,—

"Good God, are you all mad?"

Henry relaxed his hold, and looked in his face.

"Gracious heavens, it is Mr. Holland!"he said.

"Yes; did you not know me?"

Henry was bewildered.He staggered to a seat, and, in doing so, he saw his mother, stretched apparently lifeless upon the floor.To raise her was the work of a moment, and then Marchdale and George, who had followed him as fast as they could, appeared at the open window.

Such a strange scene as that small room now exhibited had never been equalled in Bannerworth Hall.There was young Mr. Holland, of whom mention has already been made, as the affianced lover of Flora, supporting her fainting form.There was Henry doing equal service to his mother; and on the floor lay the two pistols, and one of the candles which had been upset in the confusion; while the terrified attitudes of George and Mr. Marchdale at the window completed the strange-looking picture.

"What is this—oh!what has happened?"cried George.

"I know not—I know not," said Henry."Some one summon the servants; I am nearly mad."

Mr. Marchdale at once rung the bell, for George looked so faint and ill as to be incapable of doing so; and he rung it so loudly and so effectually, that the two servants who had been employed suddenly upon the others leaving came with much speed to know what was the matter.

"See to your mistress," said Henry."She is dead, or has fainted.For God's sake, let who can give me some account of what has caused all this confusion here."

"Are you aware, Henry," said Marchdale, "that a stranger is present in the room?"

He pointed to Mr. Holland as he spoke, who, before Henry could reply, said,—

"Sir, I may be a stranger to you, as you are to me, and yet no stranger to those whose home this is."

"No, no," said Henry, "you are no stranger to us, Mr. Holland, but are thrice welcome—none can be more welcome.Mr. Marchdale, this is Mr Holland, of whom you have heard me speak."

"I am proud to know you, sir," said Marchdale.

"Sir, I thank you," replied Holland, coldly.

It will so happen; but, at first sight, it appeared as if those two persons had some sort of antagonistic feeling towards each other, which threatened to prevent effectually their ever becoming intimate friends.

The appeal of Henry to the servants to know if they could tell him what had occurred was answered in the negative.All they knew was that they had heard two shots fired, and that, since then, they had remained where they were, in a great fright, until the bell was rung violently.This was no news at all and, therefore, the only chance was, to wait patiently for the recovery of the mother, or of Flora, from one or the other of whom surely some information could be at once then procured.

Mrs. Bannerworth was removed to her own room, and so would Flora have been; but Mr. Holland, who was supporting her in his arms, said,—

"I think the air from the open window is recovering her, and it is likely to do so.Oh, do not now take her from me, after so long an absence.Flora, Flora, look up; do you not know me?You have not yet given me one look of acknowledgment.Flora, dear Flora!"

The sound of his voice seemed to act as the most potent of charms in restoring her to consciousness; it broke through the death-like trance in which she lay, and, opening her beautiful eyes, she fixed them upon his face, saying,—

"Yes, yes; it is Charles—it is Charles."

She burst into a hysterical flood of tears, and clung to him like some terrified child to its only friend in the whole wide world.

"Oh, my dear friends," cried Charles Holland, "do not deceive me; has Flora been ill?"

"We have all been ill," said George.

"All ill?"

"Ay, and nearly mad," exclaimed Harry.

Holland looked from one to the other in surprise, as well he might, nor was that surprise at all lessened when Flora made an effort to extricate herself from his embrace, as she exclaimed,—