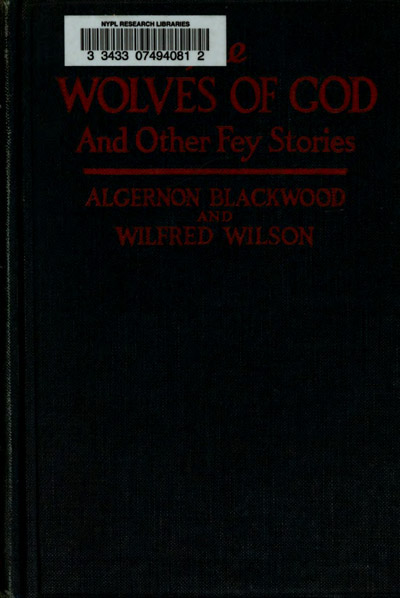

The Wolves of God, and Other Fey Stories

Summary

Play Sample

“It is time,” she said aloud.“The hour has come.My father climbs, and we must join him on the summit.Come!”

She took his hand and raised him to his feet, and together they began the rough ascent towards the Crag.As they passed along the shore of the Tarn of Blood, he saw the fire reflected in the ink-black waters; he made out, too, though dimly, a rough circle of big stones, with a larger flag-stone lying in the centre.Three small fires of bracken and wood, placed in a triangle with its apex towards the Standing Stone on the distant hill, burned briskly, the crackling material sending out sparks that pierced the columns of thick smoke.And in this smoke, peering, shifting, appearing and disappearing, it seemed he saw great faces moving.The flickering light and twirling smoke made clear sight difficult.His bliss, his lethargy were very deep.They left the tarn below them and hand in hand began to climb the final slope.

Whether the physical effort of climbing disturbed the deep pressure of the mood that numbed his senses, or whether the cold draught of wind they met upon the ridge restored some vital detail of To-day, Holt does not know.Something, at any rate, in him wavered suddenly, as though a centre of gravity had shifted slightly.There was a perceptible alteration in the balance of thought and feeling that had held invariable now for many hours.It seemed to him that something heavy lifted, or rather, began to lift—a weight, a shadow, something oppressive that obstructed light.A ray of light, as it were, struggled through the thick darkness that enveloped him.To him, as he paused on the ridge to recover his breath, came this vague suggestion of faint light breaking across the blackness.It was objective.

“See,” said the girl in a low voice, “the moon is rising. It lights the sacred island. The blood-red waters turn to silver.”

He saw, indeed, that a huge three-quarter moon now drove with almost visible movement above the distant line of hills; the little tarn gleamed as with silvery armour; the glow of the sacrificial fires showed red across it.He looked down with a shudder into the sheer depth that opened at his feet, then turned to look at his companion.He started and shrank back.Her face, lit by the moon and by the fire, shone pale as death; her black hair framed it with a terrible suggestiveness; the eyes, though brilliant as ever, had a film upon them.She stood in an attitude of both ecstasy and resignation, and one outstretched arm pointed towards the summit where her father stood.

Her lips parted, a marvellous smile broke over her features, her voice was suddenly unfamiliar: “He wears the collar,” she uttered.“Come.Our time is here at last, and we are ready.See, he waits for us!”

There rose for the first time struggle and opposition in him; he resisted the pressure of her hand that had seized his own and drew him forcibly along.Whence came the resistance and the opposition he could not tell, but though he followed her, he was aware that the refusal in him strengthened.The weight of darkness that oppressed him shifted a little more, an inner light increased; The same moment they reached the summit and stood beside—the priest.There was a curious sound of fluttering.The figure, he saw, was naked, save for a rough blanket tied loosely about the waist.

“The hour has come at last,” cried his deep booming voice that woke echoes from the dark hills about them.“We are alone now with our Gods.”And he broke then into a monotonous rhythmic chanting that rose and fell upon the wind, yet in a tongue that sounded strange; his erect figure swayed slightly with its cadences; his black beard swept his naked chest; and his face, turned skywards, shone in the mingled light of moon above and fire below, yet with an added light as well that burned within him rather than without. He was a weird, magnificent figure, a priest of ancient rites invoking his deathless deities upon the unchanging hills.

But upon Holt, too, as he stared in awed amazement, an inner light had broken suddenly.It came as with a dazzling blaze that at first paralysed thought and action.His mind cleared, but too abruptly for movement, either of tongue or hand, to be possible.Then, abruptly, the inner darkness rolled away completely.The light in the wild eyes of the great chanting, swaying figure, he now knew was the light of mania.

The faint fluttering sound increased, and the voice of the girl was oddly mingled with it.The priest had ceased his invocation.Holt, aware that he stood alone, saw the girl go past him carrying a big black bird that struggled with vainly beating wings.

“Behold the sacrifice,” she said, as she knelt before her father and held up the victim.“May the Gods accept it as presently They shall accept us too!”

The great figure stooped and took the offering, and with one blow of the knife he held, its head was severed from its body.The blood spattered on the white face of the kneeling girl.Holt was aware for the first time that she, too, was now unclothed; but for a loose blanket, her white body gleamed against the dark heather in the moonlight.At the same moment she rose to her feet, stood upright, turned towards him so that he saw the dark hair streaming across her naked shoulders, and, with a face of ecstasy, yet ever that strange film upon her eyes, her voice came to him on the wind:

“Farewell, yet not farewell!We shall meet, all three, in the underworld.The Gods accept us!”

Turning her face away, she stepped towards the ominous figure behind, and bared her ivory neck and breast to the knife.The eyes of the maniac were upon her own; she was as helpless and obedient as a lamb before his spell.

Then Holt’s horrible paralysis, if only just in time, was lifted.The priest had raised his arm, the bronze knife with its ragged edge gleamed in the air, with the other hand he had already gathered up the thick dark hair, so that the neck lay bare and open to the final blow.But it was two other details, Holt thinks, that set his muscles suddenly free, enabling him to act with the swift judgment which, being wholly unexpected, disconcerted both maniac and victim and frustrated the awful culmination.The dark spots of blood upon the face he loved, and the sudden final fluttering of the dead bird’s wings upon the ground—these two things, life actually touching death, released the held-back springs.

He leaped forward.He received the blow upon his left arm and hand.It was his right fist that sent the High Priest to earth with a blow that, luckily, felled him in the direction away from the dreadful brink, and it was his right arm and hand, he became aware some time afterwards only, that were chiefly of use in carrying the fainting girl and her unconscious father back to the shelter of the cottage, and to the best help and comfort he could provide....

It was several years afterwards, in a very different setting, that he found himself spelling out slowly to a little boy the lettering cut into a circlet of bronze the child found on his study table.To the child he told a fairy tale, then dismissed him to play with his mother in the garden.But, when alone, he rubbed away the verdigris with great care, for the circlet was thin and frail with age, as he examined again the little picture of a tripod from which smoke issued, incised neatly in the metal.Below it, almost as sharp as when the Roman craftsman cut it first, was the name Acella.He touched the letters tenderly with his left hand, from which two fingers were missing, then placed it in a drawer of his desk and turned the key.

“That curious name,” said a low voice behind his chair.His wife had come in and was looking over his shoulder.“You love it, and I dread it.”She sat on the desk beside him, her eyes troubled.“It was the name father used to call me in his illness.”

Her husband looked at her with passionate tenderness, but said no word.

“And this,” she went on, taking the broken hand in both her own, “is the price you paid to me for his life.I often wonder what strange good deity brought you upon the lonely moor that night, and just in the very nick of time.You remember...?”

“The deity who helps true lovers, of course,” he said with a smile, evading the question. The deeper memory, he knew, had closed absolutely in her since the moment of the attempted double crime. He kissed her, murmuring to himself as he did so, but too low for her to hear, “Acella! My Acella...!”

VI

THE VALLEY OF THE BEASTS

1

As they emerged suddenly from the dense forest the Indian halted, and Grimwood, his employer, stood beside him, gazing into the beautiful wooded valley that lay spread below them in the blaze of a golden sunset. Both men leaned upon their rifles, caught by the enchantment of the unexpected scene.

“We camp here,” said Tooshalli abruptly, after a careful survey.“To-morrow we make a plan.”

He spoke excellent English.The note of decision, almost of authority, in his voice was noticeable, but Grimwood set it down to the natural excitement of the moment.Every track they had followed during the last two days, but one track in particular as well, had headed straight for this remote and hidden valley, and the sport promised to be unusual.

“That’s so,” he replied, in the tone of one giving an order.“You can make camp ready at once.”And he sat down on a fallen hemlock to take off his moccasin boots and grease his feet that ached from the arduous day now drawing to a close.Though under ordinary circumstances he would have pushed on for another hour or two, he was not averse to a night here, for exhaustion had come upon him during the last bit of rough going, his eye and muscles were no longer steady, and it was doubtful if he could have shot straight enough to kill.He did not mean to miss a second time.

With his Canadian friend, Iredale, the latter’s half-breed, and his own Indian, Tooshalli, the party had set out three weeks ago to find the “wonderful big moose” the Indians reported were travelling in the Snow River country.They soon found that the tale was true; tracks were abundant; they saw fine animals nearly every day, but though carrying good heads, the hunters expected better still and left them alone.Pushing up the river to a chain of small lakes near its source, they then separated into two parties, each with its nine-foot bark canoe, and packed in for three days after the yet bigger animals the Indians agreed would be found in the deeper woods beyond.Excitement was keen, expectation keener still.The day before they separated, Iredale shot the biggest moose of his life, and its head, bigger even than the grand Alaskan heads, hangs in his house to-day.Grimwood’s hunting blood was fairly up.His blood was of the fiery, not to say ferocious, quality.It almost seemed he liked killing for its own sake.

Four days after the party broke into two he came upon a gigantic track, whose measurements and length of stride keyed every nerve he possessed to its highest tension.

Tooshalli examined the tracks for some minutes with care.“It is the biggest moose in the world,” he said at length, a new expression on his inscrutable red visage.

Following it all that day, they yet got no sight of the big fellow that seemed to be frequenting a little marshy dip of country, too small to be called valley, where willow and undergrowth abounded.He had not yet scented his pursuers.They were after him again at dawn.Towards the evening of the second day Grimwood caught a sudden glimpse of the monster among a thick clump of willows, and the sight of the magnificent head that easily beat all records set his heart beating like a hammer with excitement.He aimed and fired.But the moose, instead of crashing, went thundering away through the further scrub and disappeared, the sound of his plunging canter presently dying away. Grimwood had missed, even if he had wounded.

They camped, and all next day, leaving the canoe behind, they followed the huge track, but though finding signs of blood, these were not plentiful, and the shot had evidently only grazed the animal.The travelling was of the hardest.Towards evening, utterly exhausted, the spoor led them to the ridge they now stood upon, gazing down into the enchanting valley that opened at their feet.The giant moose had gone down into this valley.He would consider himself safe there.Grimwood agreed with the Indian’s judgment.They would camp for the night and continue at dawn the wild hunt after “the biggest moose in the world.”

Supper was over, the small fire used for cooking dying down, with Grimwood became first aware that the Indian was not behaving quite as usual.What particular detail drew his attention is hard to say.He was a slow-witted, heavy man, full-blooded, unobservant; a fact had to hurt him through his comfort, through his pleasure, before he noticed it.Yet anyone else must have observed the changed mood of the Redskin long ago.Tooshalli had made the fire, fried the bacon, served the tea, and was arranging the blankets, his own and his employer’s, before the latter remarked upon his—silence.Tooshalli had not uttered a word for over an hour and a half, since he had first set eyes upon the new valley, to be exact.And his employer now noticed the unaccustomed silence, because after food he liked to listen to wood talk and hunting lore.

“Tired out, aren’t you?”said big Grimwood, looking into the dark face across the firelight.He resented the absence of conversation, now that he noticed it.He was over-weary himself, he felt more irritable than usual, though his temper was always vile.

“Lost your tongue, eh?”he went on with a growl, as the Indian returned his stare with solemn, expressionless face. That dark inscrutable look got on his nerves a bit. “Speak up, man!” he exclaimed sharply. “What’s it all about?”

The Englishman had at last realized that there was something to “speak up” about.The discovery, in his present state, annoyed him further.Tooshalli stared gravely, but made no reply.The silence was prolonged almost into minutes.Presently the head turned sideways, as though the man listened.The other watched him very closely, anger growing in him.

But it was the way the Redskin turned his head, keeping his body rigid, that gave the jerk to Grimwood’s nerves, providing him with a sensation he had never known in his life before—it gave him what is generally called “the goose-flesh.”It seemed to jangle his entire system, yet at the same time made him cautious.He did not like it, this combination of emotions puzzled him.

“Say something, I tell you,” he repeated in a harsher tone, raising his voice.He sat up, drawing his great body closer to the fire.“Say something, damn it!”

His voice fell dead against the surrounding trees, making the silence of the forest unpleasantly noticeable.Very still the great woods stood about them; there was no wind, no stir of branches; only the crackle of a snapping twig was audible from time to time, as the night-life moved unwarily sometimes watching the humans round their little fire.The October air had a frosty touch that nipped.

The Redskin did not answer.No muscle of his neck nor of his stiffened body moved.He seemed all ears.

“Well?”repeated the Englishman, lowering his voice this time instinctively.“What d’you hear, God damn it!”The touch of odd nervousness that made his anger grow betrayed itself in his language.

Tooshalli slowly turned his head back again to its normal position, the body rigid as before.

“I hear nothing, Mr. Grimwood,” he said, gazing with quiet dignity into his employer’s eyes.

This was too much for the other, a man of savage temper at the best of times.He was the type of Englishman who held strong views as to the right way of treating “inferior” races.

“That’s a lie, Tooshalli, and I won’t have you lie to me.Now what was it?Tell me at once!”

“I hear nothing,” repeated the other.“I only think.”

“And what is it you’re pleased to think?”Impatience made a nasty expression round the mouth.

“I go not,” was the abrupt reply, unalterable decision in the voice.

The man’s rejoinder was so unexpected that Grimwood found nothing to say at first.For a moment he did not take its meaning; his mind, always slow, was confused by impatience, also by what he considered the foolishness of the little scene.Then in a flash he understood; but he also understood the immovable obstinacy of the race he had to deal with.Tooshalli was informing him that he refused to go into the valley where the big moose had vanished.And his astonishment was so great at first that he merely sat and stared.No words came to him.

“It is——” said the Indian, but used a native term.

“What’s that mean?”Grimwood found his tongue, but his quiet tone was ominous.

“Mr. Grimwood, it mean the ‘Valley of the Beasts,’” was the reply in a tone quieter still.

The Englishman made a great, a genuine effort at self-control.He was dealing, he forced himself to remember, with a superstitious Redskin.He knew the stubbornness of the type.If the man left him his sport was irretrievably spoilt, for he could not hunt in this wilderness alone, and even if he got the coveted head, he could never, never get it out alone.His native selfishness seconded his effort.Persuasion, if only he could keep back his rising anger, was his rôle to play.

“The Valley of the Beasts,” he said, a smile on his lips rather than in his darkening eyes; “but that’s just what we want. It’s beasts we’re after, isn’t it?” His voice had a false cheery ring that could not have deceived a child. “But what d’you mean, anyhow—the Valley of the Beasts?” He asked it with a dull attempt at sympathy.

“It belong to Ishtot, Mr. Grimwood.”The man looked him full in the face, no flinching in the eyes.

“My—our—big moose is there,” said the other, who recognized the name of the Indian Hunting God, and understanding better, felt confident he would soon persuade his man.Tooshalli, he remembered, too, was nominally a Christian.“We’ll follow him at dawn and get the biggest head the world has ever seen.You will be famous,” he added, his temper better in hand again.“Your tribe will honour you.And the white hunters will pay you much money.”

“He go there to save himself.I go not.”

The other’s anger revived with a leap at this stupid obstinacy.But, in spite of it, he noticed the odd choice of words.He began to realize that nothing now would move the man.At the same time he also realized that violence on his part must prove worse than useless.Yet violence was natural to his “dominant” type.“That brute Grimwood” was the way most men spoke of him.

“Back at the settlement you’re a Christian, remember,” he tried, in his clumsy way, another line.“And disobedience means hell-fire.You know that!”

“I a Christian—at the post,” was the reply, “but out here the Red God rule.Ishtot keep that valley for himself.No Indian hunt there.”It was as though a granite boulder spoke.

The savage temper of the Englishman, enforced by the long difficult suppression, rose wickedly into sudden flame.He stood up, kicking his blankets aside.He strode across the dying fire to the Indian’s side.Tooshalli also rose.They faced each other, two humans alone in the wilderness, watched by countless invisible forest eyes.

Tooshalli stood motionless, yet as though he expected violence from the foolish, ignorant white-face. “You go alone, Mr. Grimwood.” There was no fear in him.

Grimwood choked with rage.His words came forth with difficulty, though he roared them into the silence of the forest:

“I pay you, don’t I? You’ll do what I say, not what you say!” His voice woke the echoes.

The Indian, arms hanging by his side, gave the old reply.

“I go not,” he repeated firmly.

It stung the other into uncontrollable fury.

The beast then came uppermost; it came out.“You’ve said that once too often, Tooshalli!”and he struck him brutally in the face.The Indian fell, rose to his knees again, collapsed sideways beside the fire, then struggled back into a sitting position.He never once took his eyes from the white man’s face.

Beside himself with anger, Grimwood stood over him.“Is that enough?Will you obey me now?”he shouted.

“I go not,” came the thick reply, blood streaming from his mouth. The eyes had no flinching in them. “That valley Ishtot keep. Ishtot see us now. He see you.” The last words he uttered with strange, almost uncanny emphasis.

Grimwood, arm raised, fist clenched, about to repeat his terrible assault, paused suddenly. His arm sank to his side. What exactly stopped him he could never say. For one thing, he feared his own anger, feared that if he let himself go he would not stop till he had killed—committed murder. He knew his own fearful temper and stood afraid of it. Yet it was not only that. The calm firmness of the Redskin, his courage under pain, and something in the fixed and burning eyes arrested him. Was it also something in the words he had used—“Ishtot see you”—that stung him into a queer caution midway in his violence?

He could not say.He only knew that a momentary sense of awe came over him. He became unpleasantly aware of the enveloping forest, so still, listening in a kind of impenetrable, remorseless silence. This lonely wilderness, looking silently upon what might easily prove murder, laid a faint, inexplicable chill upon his raging blood. The hand dropped slowly to his side again, the fist unclenched itself, his breath came more evenly.

“Look you here,” he said, adopting without knowing it the local way of speech.“I ain’t a bad man, though your going-on do make a man damned tired.I’ll give you another chance.”His voice was sullen, but a new note in it surprised even himself.“I’ll do that.You can have the night to think it over, Tooshalli—see?Talk it over with your——”

He did not finish the sentence.Somehow the name of the Redskin God refused to pass his lips.He turned away, flung himself into his blankets, and in less than ten minutes, exhausted as much by his anger as by the day’s hard going, he was sound asleep.

The Indian, crouching beside the dying fire, had said nothing.

Night held the woods, the sky was thick with stars, the life of the forest went about its business quietly, with that wondrous skill which millions of years have perfected.The Redskin, so close to this skill that he instinctively used and borrowed from it, was silent, alert and wise, his outline as inconspicuous as though he merged, like his four-footed teachers, into the mass of the surrounding bush.

He moved perhaps, yet nothing knew he moved.His wisdom, derived from that eternal, ancient mother who from infinite experience makes no mistakes, did not fail him.His soft tread made no sound; his breathing, as his weight, was calculated.The stars observed him, but they did not tell; the light air knew his whereabouts, yet without betrayal....

The chill dawn gleamed at length between the trees, lighting the pale ashes of an extinguished fire, also of a bulky, obvious form beneath a blanket. The form moved clumsily. The cold was penetrating.

And that bulky form now moved because a dream had come to trouble it.A dark figure stole across its confused field of vision.The form started, but it did not wake.The figure spoke: “Take this,” it whispered, handing a little stick, curiously carved.“It is the totem of great Ishtot.In the valley all memory of the White Gods will leave you.Call upon Ishtot....Call on Him if you dare”; and the dark figure glided away out of the dream and out of all remembrance....

2

The first thing Grimwood noticed when he woke was that Tooshalli was not there.No fire burned, no tea was ready.He felt exceedingly annoyed.He glared about him, then got up with a curse to make the fire.His mind seemed confused and troubled.At first he only realized one thing clearly—his guide had left him in the night.

It was very cold.He lit the wood with difficulty and made his tea, and the actual world came gradually back to him.The Red Indian had gone; perhaps the blow, perhaps the superstitious terror, perhaps both, had driven him away.He was alone, that was the outstanding fact.For anything beyond outstanding facts, Grimwood felt little interest.Imaginative speculation was beyond his compass.Close to the brute creation, it seemed, his nature lay.

It was while packing his blankets—he did it automatically, a dull, vicious resentment in him—that his fingers struck a bit of wood that he was about to throw away when its unusual shape caught his attention suddenly.His odd dream came back then.But was it a dream?The bit of wood was undoubtedly a totem stick. He examined it. He paid it more attention than he meant to, wished to. Yes, it was unquestionably a totem stick. The dream, then, was not a dream. Tooshalli had quit, but, following with Redskin faithfulness some code of his own, had left him the means of safety. He chuckled sourly, but thrust the stick inside his belt. “One never knows,” he mumbled to himself.

He faced the situation squarely. He was alone in the wilderness. His capable, experienced woodsman had deserted him. The situation was serious. What should he do? A weakling would certainly retrace his steps, following the track they had made, afraid to be left alone in this vast hinterland of pathless forest. But Grimwood was of another build. Alarmed he might be, but he would not give in. He had the defects of his own qualities. The brutality of his nature argued force. He was determined and a sportsman. He would go on. And ten minutes after breakfast, having first made a cache of what provisions were left over, he was on his way—down across the ridge and into the mysterious valley, the Valley of the Beasts.

It looked, in the morning sunlight, entrancing.The trees closed in behind him, but he did not notice.It led him on....

He followed the track of the gigantic moose he meant to kill, and the sweet, delicious sunshine helped him.The air was like wine, the seductive spoor of the great beast, with here and there a faint splash of blood on leaves or ground, lay forever just before his eyes.He found the valley, though the actual word did not occur to him, enticing; more and more he noticed the beauty, the desolate grandeur of the mighty spruce and hemlock, the splendour of the granite bluffs which in places rose above the forest and caught the sun....The valley was deeper, vaster than he had imagined.He felt safe, at home in it, though, again these actual terms did not occur to him....Here he could hide for ever and find peace....He became aware of a new quality in the deep loneliness. The scenery for the first time in his life appealed to him, and the form of the appeal was curious—he felt the comfort of it.

For a man of his habit, this was odd, yet the new sensations stole over him so gently, their approach so gradual, that they were first recognized by his consciousness indirectly.They had already established themselves in him before he noticed them; and the indirectness took this form—that the passion of the chase gave place to an interest in the valley itself.The lust of the hunt, the fierce desire to find and kill, the keen wish, in a word, to see his quarry within range, to aim, to fire, to witness the natural consummation of the long expedition—these had all become measurably less, while the effect of the valley upon him had increased in strength.There was a welcome about it that he did not understand.

The change was singular, yet, oddly enough, it did not occur to him as singular; it was unnatural, yet it did not strike him so.To a dull mind of his unobservant, unanalytical type, a change had to be marked and dramatic before he noticed it; something in the nature of a shock must accompany it for him to recognize it had happened.And there had been no shock.The spoor of the great moose was much cleaner, now that he caught up with the animal that made it; the blood more frequent; he had noticed the spot where it had rested, its huge body leaving a marked imprint on the soft ground; where it had reached up to eat the leaves of saplings here and there was also visible; he had come undoubtedly very near to it, and any minute now might see its great bulk within range of an easy shot.Yet his ardour had somehow lessened.

He first realized this change in himself when it suddenly occurred to him that the animal itself had grown less cautious.It must scent him easily now, since a moose, its sight being indifferent, depends chiefly for its safety upon its unusually keen sense of smell, and the wind came from behind him. This now struck him as decidedly uncommon: the moose itself was obviously careless of his close approach. It felt no fear.

It was this inexplicable alteration in the animal’s behaviour that made him recognize, at last, the alteration in his own.He had followed it now for a couple of hours and had descended some eight hundred to a thousand feet; the trees were thinner and more sparsely placed; there were open, park-like places where silver birch, sumach and maple splashed their blazing colours; and a crystal stream, broken by many waterfalls, foamed past towards the bed of the great valley, yet another thousand feet below.By a quiet pool against some over-arching rocks, the moose had evidently paused to drink, paused at its leisure, moreover.Grimwood, rising from a close examination of the direction the creature had taken after drinking—the hoof-marks were fresh and very distinct in the marshy ground about the pool—looked suddenly straight into the great creature’s eyes.It was not twenty yards from where he stood, yet he had been standing on that spot for at least ten minutes, caught by the wonder and loneliness of the scene.The moose, therefore, had been close beside him all this time.It had been calmly drinking, undisturbed by his presence, unafraid.

The shock came now, the shock that woke his heavy nature into realization.For some seconds, probably for minutes, he stood rooted to the ground, motionless, hardly breathing.He stared as though he saw a vision.The animal’s head was lowered, but turned obliquely somewhat, so that the eyes, placed sideways in its great head, could see him properly; its immense proboscis hung as though stuffed upon an English wall; he saw the fore-feet planted wide apart, the slope of the enormous shoulders dropping back towards the fine hind-quarters and lean flanks.It was a magnificent bull.The horns and head justified his wildest expectations, they were superb, a record specimen, and a phrase—where had he heard it? —ran vaguely, as from far distance, through his mind: “the biggest moose in the world.”

There was the extraordinary fact, however, that he did not shoot; nor feel the wish to shoot.The familiar instinct, so strong hitherto in his blood, made no sign; the desire to kill apparently had left him.To raise his rifle, aim and fire had become suddenly an absolute impossibility.

He did not move.The animal and the human stared into each other’s eyes for a length of time whose interval he could not measure.Then came a soft noise close beside him: the rifle had slipped from his grasp and fallen with a thud into the mossy earth at his feet.And the moose, for the first time now, was moving.With slow, easy stride, its great weight causing a squelching sound as the feet drew out of the moist ground, it came towards him, the bulk of the shoulders giving it an appearance of swaying like a ship at sea.It reached his side, it almost touched him, the magnificent head bent low, the spread of the gigantic horns lay beneath his very eyes.He could have patted, stroked it.He saw, with a touch of pity, that blood trickled from a sore in its left shoulder, matting the thick hair.It sniffed the fallen rifle.

Then, lifting its head and shoulders again, it sniffed the air, this time with an audible sound that shook from Grimwood’s mind the last possibility that he witnessed a vision or dreamed a dream.One moment it gazed into his face, its big brown eyes shining and unafraid, then turned abruptly, and swung away at a speed ever rapidly increasing across the park-like spaces till it was lost finally among the dark tangle of undergrowth beyond.And the Englishman’s muscles turned to paper, his paralysis passed, his legs refused to support his weight, and he sank heavily to the ground....

3

It seems he slept, slept long and heavily; he sat up, stretched himself, yawned and rubbed his eyes.The sun had moved across the sky, for the shadows, he saw, now ran from west to east, and they were long shadows.He had slept evidently for hours, and evening was drawing in.He was aware that he felt hungry.In his pouchlike pockets, he had dried meat, sugar, matches, tea, and the little billy that never left him.He would make a fire, boil some tea and eat.

But he took no steps to carry out his purpose, he felt disinclined to move, he sat thinking, thinking....What was he thinking about?He did not know, he could not say exactly; it was more like fugitive pictures that passed across his mind.Who, and where, was he?This was the Valley of the Beasts, that he knew; he felt sure of nothing else.How long had he been here, and where had he come from, and why?The questions did not linger for their answers, almost as though his interest in them was merely automatic.He felt happy, peaceful, unafraid.

He looked about him, and the spell of this virgin forest came upon him like a charm; only the sound of falling water, the murmur of wind sighing among innumerable branches, broke the enveloping silence.Overhead, beyond the crests of the towering trees, a cloudless evening sky was paling into transparent orange, opal, mother of pearl.He saw buzzards soaring lazily.A scarlet tanager flashed by.Soon would the owls begin to call and the darkness fall like a sweet black veil and hide all detail, while the stars sparkled in their countless thousands....

A glint of something that shone upon the ground caught his eye—a smooth, polished strip of rounded metal: his rifle.And he started to his feet impulsively, yet not knowing exactly what he meant to do.At the sight of the weapon, something had leaped to life in him, then faded out, died down, and was gone again.

“I’m—I’m——” he began muttering to himself, but could not finish what he was about to say.His name had disappeared completely.“I’m in the Valley of the Beasts,” he repeated in place of what he sought but could not find.

This fact, that he was in the Valley of the Beasts, seemed the only positive item of knowledge that he had.About the name something known and familiar clung, though the sequence that led up to it he could not trace.Presently, nevertheless, he rose to his feet, advanced a few steps, stooped and picked up the shining metal thing, his rifle.He examined it a moment, a feeling of dread and loathing rising in him, a sensation of almost horror that made him tremble, then, with a convulsive movement that betrayed an intense reaction of some sort he could not comprehend, he flung the thing far from him into the foaming torrent.He saw the splash it made, he also saw that same instant a large grizzly bear swing heavily along the bank not a dozen yards from where he stood.It, too, heard the splash, for it started, turned, paused a second, then changed its direction and came towards him.It came up close.Its fur brushed his body.It examined him leisurely, as the moose had done, sniffed, half rose upon its terrible hind legs, opened its mouth so that red tongue and gleaming teeth were plainly visible, then flopped back upon all fours again with a deep growling that yet had no anger in it, and swung off at a quick trot back to the bank of the torrent.He had felt its hot breath upon his face, but he had felt no fear.The monster was puzzled but not hostile.It disappeared.

“They know not——” he sought for the word “man,” but could not find it.“They have never been hunted.”

The words ran through his mind, if perhaps he was not entirely certain of their meaning; they rose, as it were, automatically; a familiar sound lay in them somewhere.At the same time there rose feelings in him that were equally, though in another way, familiar and quite natural, feelings he had once known intimately but long since laid aside.

What were they?What was their origin?They seemed distant as the stars, yet were actually in his body, in his blood and nerves, part and parcel of his flesh.Long, long ago....Oh, how long, how long?

Thinking was difficult; feeling was what he most easily and naturally managed.He could not think for long; feeling rose up and drowned the effort quickly.

That huge and awful bear—not a nerve, not a muscle quivered in him as its acrid smell rose to his nostrils, its fur brushed down his legs.Yet he was aware that somewhere there was danger, though not here.Somewhere there was attack, hostility, wicked and calculated plans against him—as against that splendid, roaming animal that had sniffed, examined, then gone its own way, satisfied.Yes, active attack, hostility and careful, cruel plans against his safety, but—not here.Here he was safe, secure, at peace; here he was happy; here he could roam at will, no eye cast sideways into forest depths, no ear pricked high to catch sounds not explained, no nostrils quivering to scent alarm.He felt this, but he did not think it.He felt hungry, thirsty too.

Something prompted him now at last to act.His billy lay at his feet, and he picked it up; the matches—he carried them in a metal case whose screw top kept out all moisture—were in his hand.Gathering a few dry twigs, he stooped to light them, then suddenly drew back with the first touch of fear he had yet known.

Fire! What was fire? The idea was repugnant to him, it was impossible, he was afraid of fire. He flung the metal case after the rifle and saw it gleam in the last rays of sunset, then sink with a little splash beneath the water. Glancing down at his billy, he realized next that he could not make use of it either, nor of the dark dry dusty stuff he had meant to boil in water. He felt no repugnance, certainly no fear, in connexion with these things, only he could not handle them, he did not need them, he had forgotten, yes, “forgotten,” what they meant exactly. This strange forgetfulness was increasing in him rapidly, becoming more and more complete with every minute. Yet his thirst must be quenched.

The next moment he found himself at the water’s edge; he stooped to fill his billy; paused, hesitated, examined the rushing water, then abruptly moved a few feet higher up the stream, leaving the metal can behind him.His handling of it had been oddly clumsy, his gestures awkward, even unnatural.He now flung himself down with an easy, simple motion of his entire body, lowered his face to a quiet pool he had found, and drank his fill of the cool, refreshing liquid.But, though unaware of the fact, he did not drink.He lapped.

Then, crouching where he was, he ate the meat and sugar from his pockets, lapped more water, moved back a short distance again into the dry ground beneath the trees, but moved this time without rising to his feet, curled his body into a comfortable position and closed his eyes again to sleep....No single question now raised its head in him.He felt contentment, satisfaction only....

He stirred, shook himself, opened half an eye and saw, as he had felt already in slumber, that he was not alone.In the park-like spaces in front of him, as in the shadowed fringe of the trees at his back, there was sound and movement, the sound of stealthy feet, the movement of innumerable dark bodies.There was the pad and tread of animals, the stir of backs, of smooth and shaggy beasts, in countless numbers.Upon this host fell the light of a half moon sailing high in a cloudless sky; the gleam of stars, sparkling in the clear night air like diamonds, shone reflected in hundreds of ever-shifting eyes, most of them but a few feet above the ground.The whole valley was alive.

He sat upon his haunches, staring, staring, but staring in wonder, not in fear, though the foremost of the great host were so near that he could have stretched an arm and touched them. It was an ever-moving, ever-shifting throng he gazed at, spell-bound, in the pale light of moon and stars, now fading slowly towards the approaching dawn. And the smell of the forest itself was not sweeter to him in that moment than the mingled perfume, raw, pungent, acrid, of this furry host of beautiful wild animals that moved like a sea, with a strange murmuring, too, like sea, as the myriad feet and bodies passed to and fro together. Nor was the gleam of the starry, phosphorescent eyes less pleasantly friendly than those happy lamps that light home-lost wanderers to cosy rooms and safety. Through the wild army, in a word, poured to him the deep comfort of the entire valley, a comfort which held both the sweetness of invitation and the welcome of some magical home-coming.

No thoughts came to him, but feeling rose in a tide of wonder and acceptance.He was in his rightful place.His nature had come home.There was this dim, vague consciousness in him that after long, futile straying in another place where uncongenial conditions had forced him to be unnatural and therefore terrible, he had returned at last where he belonged.Here, in the Valley of the Beasts, he had found peace, security and happiness.He would be—he was at last—himself.

It was a marvellous, even a magical, scene he watched, his nerves at highest tension yet quite steady, his senses exquisitely alert, yet no uneasiness in the full, accurate reports they furnished.Strong as some deep flood-tide, yet dim, as with untold time and distance, rose over him the spell of long-forgotten memory of a state where he was content and happy, where he was natural.The outlines, as it were, of mighty, primitive pictures, flashed before him, yet were gone again before the detail was filled in.

He watched the great army of the animals, they were all about him now; he crouched upon his haunches in the centre of an ever-moving circle of wild forest life. Great timber wolves he saw pass to and fro, loping past him with long stride and graceful swing; their red tongues lolling out; they swarmed in hundreds. Behind, yet mingling freely with them, rolled the huge grizzlies, not clumsy as their uncouth bodies promised, but swiftly, lightly, easily, their half tumbling gait masking agility and speed. They gambolled, sometimes they rose and stood half upright, they were comely in their mass and power, they rolled past him so close that he could touch them. And the black bear and the brown went with them, bears beyond counting, monsters and little ones, a splendid multitude. Beyond them, yet only a little further back, where the park-like spaces made free movement easier, rose a sea of horns and antlers like a miniature forest in the silvery moonlight. The immense tribe of deer gathered in vast throngs beneath the starlit sky. Moose and caribou, he saw, the mighty wapiti, and the smaller deer in their crowding thousands. He heard the sound of meeting horns, the tread of innumerable hoofs, the occasional pawing of the ground as the bigger creatures manœuvred for more space about them. A wolf, he saw, was licking gently at the shoulder of a great bull-moose that had been injured. And the tide receded, advanced again, once more receded, rising and falling like a living sea whose waves were animal shapes, the inhabitants of the Valley of the Beasts.

Beneath the quiet moonlight they swayed to and fro before him.They watched him, knew him, recognized him.They made him welcome.

He was aware, moreover, of a world of smaller life that formed an under-sea, as it were, numerous under-currents rather, running in and out between the great upright legs of the larger creatures.These, though he could not see them clearly, covered the earth, he was aware, in enormous numbers, darting hither and thither, now hiding, now reappearing, too intent upon their busy purposes to pay him attention like their huger comrades, yet ever and anon tumbling against his back, cannoning from his sides, scampering across his legs even, then gone again with a scuttering sound of rapid little feet, and rushing back into the general host beyond. And with this smaller world also he felt at home.

How long he sat gazing, happy in himself, secure, satisfied, contented, natural, he could not say, but it was long enough for the desire to mingle with what he saw, to know closer contact, to become one with them all—long enough for this deep blind desire to assert itself, so that at length he began to move from his mossy seat towards them, to move, moreover, as they moved, and not upright on two feet.

The moon was lower now, just sinking behind a towering cedar whose ragged crest broke its light into silvery spray.The stars were a little paler too.A line of faint red was visible beyond the heights at the valley’s eastern end.

He paused and looked about him, as he advanced slowly, aware that the host already made an opening in their ranks and that the bear even nosed the earth in front, as though to show the way that was easiest for him to follow.Then, suddenly, a lynx leaped past him into the low branches of a hemlock, and he lifted his head to admire its perfect poise.He saw in the same instant the arrival of the birds, the army of the eagles, hawks and buzzards, birds of prey—the awakening flight that just precedes the dawn.He saw the flocks and streaming lines, hiding the whitening stars a moment as they passed with a prodigious whirr of wings.There came the hooting of an owl from the tree immediately overhead where the lynx now crouched, but not maliciously, along its branch.

He started.He half rose to an upright position.He knew not why he did so, knew not exactly why he started.But in the attempt to find his new, and, as it now seemed, his unaccustomed balance, one hand fell against his side and came in contact with a hard straight thing that projected awkwardly from his clothing. He pulled it out, feeling it all over with his fingers. It was a little stick. He raised it nearer to his eyes, examined it in the light of dawn now growing swiftly, remembered, or half remembered what it was—and stood stock still.

“The totem stick,” he mumbled to himself, yet audibly, finding his speech, and finding another thing—a glint of peering memory—for the first time since entering the valley.

A shock like fire ran through his body; he straightened himself, aware that a moment before he had been crawling upon his hands and knees; it seemed that something broke in his brain, lifting a veil, flinging a shutter free.And Memory peered dreadfully through the widening gap.

“I’m—I’m Grimwood,” his voice uttered, though below his breath.“Tooshalli’s left me.I’m alone...!”

He was aware of a sudden change in the animals surrounding him.A big, grey wolf sat three feet away, glaring into his face; at its side an enormous grizzly swayed itself from one foot to the other; behind it, as if looking over its shoulder, loomed a gigantic wapiti, its horns merged in the shadows of the drooping cedar boughs.But the northern dawn was nearer, the sun already close to the horizon.He saw details with sharp distinctness now.The great bear rose, balancing a moment on its massive hind-quarters, then took a step towards him, its front paws spread like arms. Its wicked head lolled horribly, as a huge bull-moose, lowering its horns as if about to charge, came up with a couple of long strides and joined it.A sudden excitement ran quivering over the entire host; the distant ranks moved in a new, unpleasant way; a thousand heads were lifted, ears were pricked, a forest of ugly muzzles pointed up to the wind.

And the Englishman, beside himself suddenly with a sense of ultimate terror that saw no possible escape, stiffened and stood rigid.The horror of his position petrified him. Motionless and silent he faced the awful army of his enemies, while the white light of breaking day added fresh ghastliness to the scene which was the setting for his cruel death in the Valley of the Beasts.

Above him crouched the hideous lynx, ready to spring the instant he sought safety in the tree; above it again, he was aware of a thousand talons of steel, fierce hooked beaks of iron, and the angry beating of prodigious wings.

He reeled, for the grizzly touched his body with its outstretched paw; the wolf crouched just before its deadly spring; in another second he would have been torn to pieces, crushed, devoured, when terror, operating naturally as ever, released the muscles of his throat and tongue.He shouted with what he believed was his last breath on earth.He called aloud in his frenzy.It was a prayer to whatever gods there be, it was an anguished cry for help to heaven.

“Ishtot!Great Ishtot, help me!”his voice rang out, while his hand still clutched the forgotten totem stick.

And the Red Heaven heard him.

Grimwood that same instant was aware of a presence that, but for his terror of the beasts, must have frightened him into sheer unconsciousness.A gigantic Red Indian stood before him.Yet, while the figure rose close in front of him, causing the birds to settle and the wild animals to crouch quietly where they stood, it rose also from a great distance, for it seemed to fill the entire valley with its influence, its power, its amazing majesty.In some way, moreover, that he could not understand, its vast appearance included the actual valley itself with all its trees, its running streams, its open spaces and its rocky bluffs.These marked its outline, as it were, the outline of a superhuman shape.There was a mighty bow, there was a quiver of enormous arrows, there was this Redskin figure to whom they belonged.

Yet the appearance, the outline, the face and figure too—these were the valley; and when the voice became audible, it was the valley itself that uttered the appalling words. It was the voice of trees and wind, and of running, falling water that woke the echoes in the Valley of the Beasts, as, in that same moment, the sun topped the ridge and filled the scene, the outline of the majestic figure too, with a flood of dazzling light:

“You have shed blood in this my valley.... I will not save...!”

The figure melted away into the sunlit forest, merging with the new-born day.But Grimwood saw close against his face the shining teeth, hot fetid breath passed over his cheeks, a power enveloped his whole body as though a mountain crushed him.He closed his eyes.He fell.A sharp, crackling sound passed through his brain, but already unconscious, he did not hear it.

His eyes opened again, and the first thing they took in was—fire.He shrank back instinctively.

“It’s all right, old man.We’ll bring you round.Nothing to be frightened about.”He saw the face of Iredale looking down into his own.Behind Iredale stood Tooshalli.His face was swollen.Grimwood remembered the blow.The big man began to cry.

“Painful still, is it?”Iredale said sympathetically.“Here, swallow a little more of this.It’ll set you right in no time.”

Grimwood gulped down the spirit.He made a violent effort to control himself, but was unable to keep the tears back.He felt no pain.It was his heart that ached, though why or wherefore, he had no idea.

“I’m all to pieces,” he mumbled, ashamed yet somehow not ashamed.“My nerves are rotten.What’s happened?”There was as yet no memory in him.

“You’ve been hugged by a bear, old man.But no bones broken.Tooshalli saved you.He fired in the nick of time—a brave shot, for he might easily have hit you instead of the brute.”

“The other brute,” whispered Grimwood, as the whisky worked in him and memory came slowly back.

“Where are we?”he asked presently, looking about him.

He saw a lake, canoes drawn up on the shore, two tents, and figures moving.Iredale explained matters briefly, then left him to sleep a bit.Tooshalli, it appeared, travelling without rest, had reached Iredale’s camping ground twenty-four hours after leaving his employer.He found it deserted, Iredale and his Indian being on the hunt.When they returned at nightfall, he had explained his presence in his brief native fashion: “He struck me and I quit.He hunt now alone in Ishtot’s Valley of the Beasts.He is dead, I think.I come to tell you.”

Iredale and his guide, with Tooshalli as leader, started off then and there, but Grimwood had covered a considerable distance, though leaving an easy track to follow.It was the moose tracks and the blood that chiefly guided them.They came up with him suddenly enough—in the grip of an enormous bear.

It was Tooshalli that fired.

The Indian lives now in easy circumstances, all his needs cared for, while Grimwood, his benefactor but no longer his employer, has given up hunting.He is a quiet, easy-tempered, almost gentle sort of fellow, and people wonder rather why he hasn’t married.“Just the fellow to make a good father,” is what they say; “so kind, good-natured and affectionate.”Among his pipes, in a glass case over the mantlepiece, hangs a totem stick.He declares it saved his soul, but what he means by the expression he has never quite explained.

VII

THE CALL

The incident—story it never was, perhaps—began tamely, almost meanly; it ended upon a note of strange, unearthly wonder that has haunted him ever since. In Headley’s memory, at any rate, it stands out as the loveliest, the most amazing thing he ever witnessed. Other emotions, too, contributed to the vividness of the picture. That he had felt jealousy towards his old pal, Arthur Deane, shocked him in the first place; it seemed impossible until it actually happened. But that the jealousy was proved afterwards to have been without a cause shocked him still more. He felt ashamed and miserable.

For him, the actual incident began when he received a note from Mrs. Blondin asking him to the Priory for a week-end, or for longer, if he could manage it.

Captain Arthur Deane, she mentioned, was staying with her at the moment, and a warm welcome awaited him.Iris she did not mention—Iris Manning, the interesting and beautiful girl for whom it was well known he had a considerable weakness.He found a good-sized house party; there was fishing in the little Sussex river, tennis, golf not far away, while two motor cars brought the remoter country across the downs into easy reach.Also there was a bit of duck shooting for those who cared to wake at 3 a.m.and paddle up-stream to the marshes where the birds were feeding.

“Have you brought your gun?”was the first thing Arthur said to him when he arrived.“Like a fool, I left mine in town.”

“I hope you haven’t,” put in Miss Manning; “because if you have I must get up one fine morning at three o’clock.” She laughed merrily, and there was an undernote of excitement in the laugh.

Captain Headley showed his surprise.“That you were a Diana had escaped my notice, I’m ashamed to say,” he replied lightly.“Yet I’ve known you some years, haven’t I?”He looked straight at her, and the soft yet searching eye, turning from his friend, met his own securely.She was appraising him, for the hundreth time, and he, for the hundreth time, was thinking how pretty she was, and wondering how long the prettiness would last after marriage.

“I’m not,” he heard her answer.“That’s just it.But I’ve promised.”

“Rather!”said Arthur gallantly.“And I shall hold you to it,” he added still more gallantly—too gallantly, Headley thought.“I couldn’t possibly get up at cockcrow without a very special inducement, could I, now?You know me, Dick!”

“Well, anyhow, I’ve brought my gun,” Headley replied evasively, “so you’ve no excuse, either of you.You’ll have to go.”And while they were laughing and chattering about it, Mrs. Blondin clinched the matter for them.Provisions were hard to come by; the larder really needed a brace or two of birds; it was the least they could do in return for what she called amusingly her “Armistice hospitality.”

“So I expect you to get up at three,” she chaffed them, “and return with your Victory birds.”

It was from this preliminary skirmish over the tea-table on the law five minutes after his arrival that Dick Headley realized easily enough the little game in progress.As a man of experience, just on the wrong side of forty, it was not difficult to see the cards each held.He sighed.Had he guessed an intrigue was on foot he would not have come, yet he might have known that wherever his hostess was, there were the vultures gathered together. Matchmaker by choice and instinct, Mrs. Blondin could not help herself. True to her name, she was always balancing on matrimonial tightropes—for others.

Her cards, at any rate, were obvious enough; she had laid them on the table for him. He easily read her hand. The next twenty-four hours confirmed this reading. Having made up her mind that Iris and Arthur were destined for each other, she had grown impatient; they had been ten days together, yet Iris was still free. They were good friends only. With calculation, she, therefore, took a step that must bring things further. She invited Dick Headley, whose weakness for the girl was common knowledge. The card was indicated; she played it. Arthur must come to the point or see another man carry her off. This, at least, she planned, little dreaming that the dark King of Spades would interfere.

Miss Manning’s hand also was fairly obvious, for both men were extremely eligible partisShe was getting on; one or other was to become her husband before the party broke up.This, in crude language, was certainly in her cards, though, being a nice and charming girl, she might camouflage it cleverly to herself and others.Her eyes, on each man in turn when the shooting expedition was being discussed, revealed her part in the little intrigue clearly enough.It was all, thus far, as commonplace as could be.

But there were two more hands Headley had to read—his own and his friend’s; and these, he admitted honestly, were not so easy.To take his own first.It was true he was fond of the girl and had often tried to make up his mind to ask her.Without being conceited, he had good reason to believe his affection was returned and that she would accept him.There was no ecstatic love on either side, for he was no longer a boy of twenty, nor was she unscathed by tempestuous love affairs that had scorched the first bloom from her face and heart.But they understood one another; they were an honest couple; she was tired of flirting; both wanted to marry and settle down. Unless a better man turned up she probably would say “Yes” without humbug or delay. It was this last reflection that brought him to the final hand he had to read.

Here he was puzzled.Arthur Deane’s rôle in the teacup strategy, for the first time since they had known one another, seemed strange, uncertain.Why?Because, though paying no attention to the girl openly, he met her clandestinely, unknown to the rest of the house-party, and above all without telling his intimate pal—at three o’clock in the morning.

The house-party was in full swing, with a touch of that wild, reckless gaiety which followed the end of the war: “Let us be happy before a worse thing comes upon us,” was in many hearts.After a crowded day they danced till early in the morning, while doubtful weather prevented the early shooting expedition after duck.The third night Headley contrived to disappear early to bed.He lay there thinking.He was puzzled over his friend’s rôle, over the clandestine meeting in particular.It was the morning before, waking very early, he had been drawn to the window by an unusual sound—the cry of a bird.Was it a bird?In all his experience he had never heard such a curious, half-singing call before.He listened a moment, thinking it must have been a dream, yet with the odd cry still ringing in his ears.It was repeated close beneath his open window, a long, low-pitched cry with three distinct following notes in it.

He sat up in bed and listened hard.No bird that he knew could make such sounds.But it was not repeated a third time, and out of sheer curiosity he went to the window and looked out.Dawn was creeping over the distant downs; he saw their outline in the grey pearly light; he saw the lawn below, stretching down to the little river at the bottom, where a curtain of faint mist hung in the air.And on this lawn he also saw Arthur Deane—with Iris Manning.

Of course, he reflected, they were going after the duck. He turned to look at his watch; it was three o’clock. The same glance, however, showed him his gun standing in the corner. So they were going without a gun. A sharp pang of unexpected jealousy shot through him. He was just going to shout out something or other, wishing them good luck, or asking if they had found another gun, perhaps, when a cold touch crept down his spine. The same instant his heart contracted. Deane had followed the girl into the summer-house, which stood on the right. It was not the shooting expedition at all. Arthur was meeting her for another purpose. The blood flowed back, filling his head. He felt an eavesdropper, a sneak, a detective; but, for all that, he felt also jealous. And his jealousy seemed chiefly because Arthur had not told him.

Of this, then, he lay thinking in bed on the third night.The following day he had said nothing, but had crossed the corridor and put the gun in his friend’s room.Arthur, for his part, had said nothing either.For the first time in their long, long friendship, there lay a secret between them.To Headley the unexpected revelation came with pain.

For something like a quarter of a century these two had been bosom friends; they had camped together, been in the army together, taken their pleasure together, each the full confidant of the other in all the things that go to make up men’s lives.Above all, Headley had been the one and only recipient of Arthur’s unhappy love story.He knew the girl, knew his friend’s deep passion, and also knew his terrible pain when she was lost at sea.Arthur was burnt out, finished, out of the running, so far as marriage was concerned.He was not a man to love a second time.It was a great and poignant tragedy.Headley, as confidant, knew all.But more than that—Arthur, on his side, knew his friend’s weakness for Iris Manning, knew that a marriage was still possible and likely between them.They were true as steel to one another, and each man, oddly enough, had once saved the other’s life, thus adding to the strength of a great natural tie.

Yet now one of them, feigning innocence by day, even indifference, secretly met his friend’s girl by night, and kept the matter to himself.It seemed incredible.With his own eyes Headley had seen him on the lawn, passing in the faint grey light through the mist into the summer-house, where the girl had just preceded him.He had not seen her face, but he had seen the skirt sweep round the corner of the wooden pillar.He had not waited to see them come out again.

So he now lay wondering what rôle his old friend was playing in this little intrigue that their hostess, Mrs. Blondin, helped to stage.And, oddly enough, one minor detail stayed in his mind with a curious vividness.As naturalist, hunter, nature-lover, the cry of that strange bird, with its three mournful notes, perplexed him exceedingly.

A knock came at his door, and the door pushed open before he had time to answer.Deane himself came in.

“Wise man,” he exclaimed in an easy tone, “got off to bed.Iris was asking where you were.”He sat down on the edge of the mattress, where Headley was lying with a cigarette and an open book he had not read.The old sense of intimacy and comradeship rose in the latter’s heart.Doubt and suspicion faded.He prized his great friendship.He met the familiar eyes.“Impossible,” he said to himself, “absolutely impossible!He’s not playing a game; he’s not a rotter!”He pushed over his cigarette case, and Arthur lighted one.

“Done in,” he remarked shortly, with the first puff.“Can’t stand it any more.I’m off to town to-morrow.”

Headley stared in amazement.“Fed up already?”he asked.“Why, I rather like it.It’s quite amusing.What’s wrong, old man?”

“This match-making,” said Deane bluntly.“Always throwing that girl at my head.If it’s not the duck-shooting stunt at 3 a. m. , it’s something else. She doesn’t care for me and I don’t care for her. Besides——”

He stopped, and the expression of his face changed suddenly.A sad, quiet look of tender yearning came into his clear brown eyes.

“You know, Dick,” he went on in a low, half-reverent tone. “I don’t want to marry. I never can.”

Dick’s heart stirred within him.“Mary,” he said, understandingly.

The other nodded, as though the memories were still too much for him.“I’m still miserably lonely for her,” he said.“Can’t help it simply.I feel utterly lost without her.Her memory to me is everything.”He looked deep into his pal’s eyes.“I’m married to that,” he added very firmly.

They pulled their cigarettes a moment in silence.They belonged to the male type that conceals emotion behind schoolboy language.

“It’s hard luck,” said Headley gently, “rotten luck, old man, I understand.”Arthur’s head nodded several times in succession as he smoked.He made no remark for some minutes.Then presently he said, as though it had no particular importance—for thus old friends show frankness to each other—“Besides, anyhow, it’s you the girl’s dying for, not me.She’s blind as a bat, old Blondin.Even when I’m with her—thrust with her by that old matchmaker for my sins—it’s you she talks about.All the talk leads up to you and yours.She’s devilish fond of you.”He paused a moment and looked searchingly into his friend’s face.“I say, old man—are you—I mean, do you mean business there?Because—excuse me interfering—but you’d better be careful.She’s a good sort, you know, after all.”

“Yes, Arthur, I do like her a bit,” Dick told him frankly.“But I can’t make up my mind quite.You see, it’s like this——”

And they talked the matter over as old friends will, until finally Arthur chucked his cigarette into the grate and got up to go.“Dead to the world,” he said, with a yawn.“I’m off to bed.Give you a chance, too,” he added with a laugh.It was after midnight.

The other turned, as though something had suddenly occurred to him.

“By the bye, Arthur,” he said abruptly, “what bird makes this sound?I heard it the other morning.Most extraordinary cry.You know everything that flies.What is it?”And, to the best of his ability, he imitated the strange three-note cry he had heard in the dawn two mornings before.

To his amazement and keen distress, his friend, with a sound like a stifled groan, sat down upon the bed without a word.He seemed startled.His face was white.He stared.He passed a hand, as in pain, across his forehead.

“Do it again,” he whispered, in a hushed, nervous voice.“Once again—for me.”

And Headley, looking at him, repeated the queer notes, a sudden revulsion of feeling rising through him.“He’s fooling me after all,” ran in his heart, “my old, old pal——”

There was silence for a full minute. Then Arthur, stammering a bit, said lamely, a certain hush in his voice still: “Where in the world did you hear that—and when?”

Dick Headley sat up in bed.He was not going to lose this friendship, which, to him, was more than the love of woman.He must help.His pal was in distress and difficulty.There were circumstances, he realized, that might be too strong for the best man in the world—sometimes.No, by God, he would play the game and help him out!

“Arthur, old chap,” he said affectionately, almost tenderly.“I heard it two mornings ago—on the lawn below my window here. It woke me up. I—I went to look. Three in the morning, about.”

Arthur amazed him then.He first took another cigarette and lit it steadily.He looked round the room vaguely, avoiding, it seemed, the other’s eyes.Then he turned, pain in his face, and gazed straight at him.

“You saw—nothing?”he asked in a louder voice, but a voice that had something very real and true in it.It reminded Headley of the voice he heard when he was fainting from exhaustion, and Arthur had said, “Take it, I tell you.I’m all right,” and had passed over the flask, though his own throat and sight and heart were black with thirst.It was a voice that had command in it, a voice that did not lie because it could not—yet did lie and could lie—when occasion warranted.

Headley knew a second’s awful struggle.

“Nothing,” he answered quietly, after his little pause.“Why?”

For perhaps two minutes his friend hid his face.Then he looked up.

“Only,” he whispered, “because that was our secret lover’s cry.It seems so strange you heard it and not I.I’ve felt her so close of late—Mary!”

The white face held very steady, the firm lips did not tremble, but it was evident that the heart knew anguish that was deep and poignant.“We used it to call each other—in the old days.It was our private call.No one else in the world knew it but Mary and myself.”

Dick Headley was flabbergasted.He had no time to think, however.

“It’s odd you should hear it and not I,” his friend repeated.He looked hurt, bewildered, wounded.Then suddenly his face brightened.“I know,” he cried suddenly.“You and I are pretty good pals.There’s a tie between us and all that.Why, it’s tel—telepathy, or whatever they call it.That’s what it is.”

He got up abruptly.Dick could think of nothing to say but to repeat the other’s words. “Of course, of course. That’s it,” he said, “telepathy.” He stared—anywhere but at his pal.

“Night, night!”he heard from the door, and before he could do more than reply in similar vein Arthur was gone.

He lay for a long time, thinking, thinking.He found it all very strange.Arthur in this emotional state was new to him.He turned it over and over.Well, he had known good men behave queerly when wrought up.That recognition of the bird’s cry was strange, of course, but—he knew the cry of a bird when he heard it, though he might not know the actual bird.That was no human whistle.Arthur was—inventing.No, that was not possible.He was worked up, then, over something, a bit hysterical perhaps.It had happened before, though in a milder way, when his heart attacks came on.They affected his nerves and head a little, it seemed.He was a deep sort, Dick remembered.Thought turned and twisted in him, offering various solutions, some absurd, some likely.He was a nervous, high-strung fellow underneath, Arthur was.He remembered that.Also he remembered, anxiously again, that his heart was not quite sound, though what that had to do with the present tangle he did not see.

Yet it was hardly likely that he would bring in Mary as an invention, an excuse—Mary, the most sacred memory in his life, the deepest, truest, best.He had sworn, anyhow, that Iris Manning meant nothing to him.

Through all his speculations, behind every thought, ran this horrid working jealousy.It poisoned him.It twisted truth.It moved like a wicked snake through mind and heart.Arthur, gripped by his new, absorbing love for Iris Manning, lied.He couldn’t believe it, he didn’t believe it, he wouldn’t believe it—yet jealousy persisted in keeping the idea alive in him.It was a dreadful thought.He fell asleep on it.

But his sleep was uneasy with feverish, unpleasant dreams that rambled on in fragments without coming to conclusion.Then, suddenly, the cry of the strange bird came into his dream.He started, turned over, woke up.The cry still continued.It was not a dream.He jumped out of bed.

The room was grey with early morning, the air fresh and a little chill.The cry came floating over the lawn as before.He looked out, pain clutching at his heart.Two figures stood below, a man and a girl, and the man was Arthur Deane.Yet the light was so dim, the morning being overcast, that had he not expected to see his friend, he would scarcely have recognized the familiar form in that shadowy outline that stood close beside the girl.Nor could he, perhaps, have recognized Iris Manning.Their backs were to him.They moved away, disappearing again into the little summer-house, and this time—he saw it beyond question—the two were hand in hand.Vague and uncertain as the figures were in the early twilight, he was sure of that.

The first disagreeable sensation of surprise, disgust, anger that sickened him turned quickly, however, into one of another kind altogether.A curious feeling of superstitious dread crept over him, and a shiver ran again along his nerves.

“Hallo, Arthur!”he called from the window.There was no answer.His voice was certainly audible in the summer-house.But no one came.He repeated the call a little louder, waited in vain for thirty seconds, then came, the same moment, to a decision that even surprised himself, for the truth we he could no longer bear the suspense of waiting.He must see his friend at once and have it out with him.He turned and went deliberately down the corridor to Deane’s bedroom.He would wait there for his return and know the truth from his own lips.But also another thought had come—the gun.He had quite forgotten it—the safety-catch was out of order. He had not warned him.

He found the door closed but not locked; opening it cautiously, he went in.

But the unexpectedness of what he saw gave him a genuine shock.He could hardly suppress a cry.Everything in the room was neat and orderly, no sign of disturbance anywhere, and it was not empty.There, in bed, before his very eyes, was Arthur.The clothes were turned back a little; he saw the pyjamas open at the throat; he lay sound asleep, deeply, peacefully asleep.

So surprised, indeed, was Headley that, after staring a moment, almost unable to believe his sight, he then put out a hand and touched him gently, cautiously on the forehead.But Arthur did not stir or wake; his breathing remained deep and regular.He lay sleeping like a baby.

Headley glanced round the room, noticed the gun in the corner where he himself had put it the day before, and then went out, closing the door behind him softly.

Arthur Deane, however, did not leave for London as he had intended, because he felt unwell and kept to his room upstairs.It was only a slight attack, apparently, but he must lie quiet.There was no need to send for a doctor; he knew just what to do; these passing attacks were common enough.He would be up and about again very shortly.Headley kept him company, saying no single word of what had happened.He read aloud to him, chatted and cheered him up.He had no other visitors.Within twenty-four hours he was himself once more.He and his friend had planned to leave the following day.

But Headley, that last night in the house, felt an odd uneasiness and could not sleep.All night long he sat up reading, looking out of the window, smoking in a chair where he could see the stars and hear the wind and watch the huge shadow of the downs.The house lay very still as the hours passed.He dozed once or twice.Why did he sit up in this unnecessary way?Why did he leave his door ajar so that the slightest sound of another door opening, or of steps passing along the corridor, must reach him? Was he anxious for his friend? Was he suspicious? What was his motive, what his secret purpose?

Headley did not know, and could not even explain it to himself.He felt uneasy, that was all he knew.Not for worlds would he have let himself go to sleep or lose full consciousness that night.It was very odd; he could not understand himself.He merely obeyed a strange, deep instinct that bade him wait and watch.His nerves were jumpy; in his heart lay some unexplicable anxiety that was pain.

The dawn came slowly; the stars faded one by one; the line of the downs showed their grand bare curves against the sky; cool and cloudless the September morning broke above the little Sussex pleasure house.He sat and watched the east grow bright.The early wind brought a scent of marshes and the sea into his room.Then suddenly it brought a sound as well—the haunting cry of the bird with its three following notes.And this time there came an answer.

Headley knew then why he had sat up.A wave of emotion swept him as he heard—an emotion he could not attempt to explain.Dread, wonder, longing seized him.For some seconds he could not leave his chair because he did not dare to.The low-pitched cries of call and answer rang in his ears like some unearthly music.With an effort he started up, went to the window and looked out.

This time the light was sharp and clear.No mist hung in the air.He saw the crimsoning sky reflected like a band of shining metal in the reach of river beyond the lawn.He saw dew on the grass, a sheet of pallid silver.He saw the summer-house, empty of any passing figures.For this time the two figures stood plainly in view before his eyes upon the lawn.They stood there, hand in hand, sharply defined, unmistakable in form and outline, their faces, moreover, turned upwards to the window where he stood, staring down in pain and amazement at them—at Arthur Deane and Mary

They looked into his eyes.He tried to call, but no sound left his throat.They began to move across the dew-soaked lawn.They went, he saw, with a floating, undulating motion towards the river shining in the dawn.Their feet left no marks upon the grass.They reached the bank, but did not pause in their going.They rose a little, floating like silent birds across the river.Turning in mid-stream, they smiled towards him, waved their hands with a gesture of farewell, then, rising still higher into the opal dawn, their figures passed into the distance slowly, melting away against the sunlit marshes and the shadowing downs beyond.They disappeared.

Headley never quite remembers actually leaving the window, crossing the room, or going down the passage.Perhaps he went at once, perhaps he stood gazing into the air above the downs for a considerable time, unable to tear himself away.He was in some marvellous dream, it seemed.The next thing he remembers, at any rate, was that he was standing beside his friend’s bed, trying, in his distraught anguish of heart, to call him from that sleep which, on earth, knows no awakening.

VIII

EGYPTIAN SORCERY

1

Sanfield paused as he was about to leave the Underground station at Victoria, and cursed the weather. When he left the City it was fine; now it was pouring with rain, and he had neither overcoat nor umbrella. Not a taxi was discoverable in the dripping gloom. He would get soaked before he reached his rooms in Sloane Street.