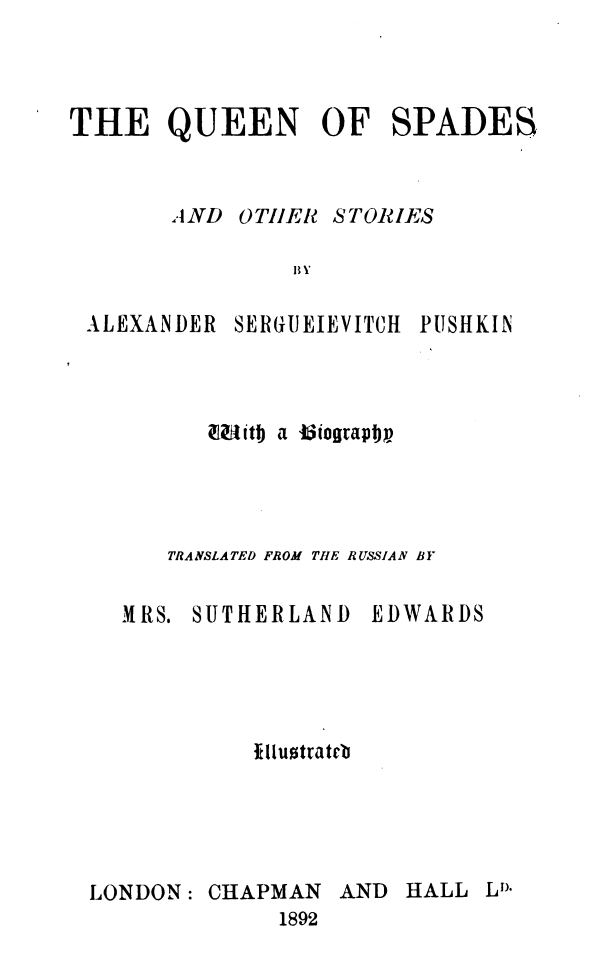

The Queen of Spades, and other stories

Summary

Play Sample

"A TIME OF GLORY AND DELIGHT."

In these places the appearance of an officer became for him a veritable triumph.The accepted lover in plain clothes fared badly by his side.

We have already said that, in spite of her coldness, Maria was still, as before, surrounded by suitors.But all had to fall in the rear when there arrived at her castle the wounded young colonel of Hussars—Burmin by name—with the order of St.George in his button-hole, and an interesting pallor on his face.He was about twenty-six.He had come home on leave to his estates, which were close to Maria's villa.Maria paid him such attention as none of the others received.In his presence her habitual gloom disappeared.It could not be said that she flirted with him.But a poet, observing her behaviour, might have asked, "S' amor non è, che dunque?"

Burmin was really a very agreeable young man.He possessed just the kind of sense that pleased women: a sense of what is suitable and becoming.He had no affectation, and was carelessly satirical.His manner towards Maria was simple and easy.He seemed to be of a quiet and modest disposition; but rumour said that he had at one time been terribly wild.This, however, did not harm him in the opinion of Maria, who (like all other young ladies) excused, with pleasure, vagaries which were the result of impulsiveness and daring.

But above all—more than his love-making, more than his pleasant talk, more than his interesting pallor, more even than his bandaged arm—the silence of the young Hussar excited her curiosity and her imagination.She could not help confessing to herself that he pleased her very much.Probably he too, with his acuteness and his experience, had seen that he interested her.How was it, then, that up to this moment she had not seen him at her feet; had not received from him any declaration whatever?And wherefore did she not encourage him with more attention, and, according to circumstances, even with tenderness?Had she a secret of her own which would account for her behaviour?

At last, Burmin fell into such deep meditation, and his black eyes rested with such fire upon Maria, that the decisive moment seemed very near.The neighbours spoke of the marriage as an accomplished fact, and kind Praskovia rejoiced that her daughter had at last found for herself a worthy mate.

The lady was sitting alone once in the drawing-room, laying out grande-patience, when Burmin entered the room, and at once inquired for Maria.

"She is in the garden," replied the old lady: "go to her, and I will wait for you here."Burmin went, and the old lady made the sign of the cross and thought, "Perhaps the affair will be settled to-day!"

Burmin found Maria in the ivy-bower beside the pond, with a book in her hands, and wearing a white dress—a veritable heroine of romance.After the first inquiries, Maria purposely let the conversation drop; increasing by these means the mutual embarrassment, from which it was only possible to escape by means of a sudden and positive declaration.

It happened thus.Burmin, feeling the awkwardness of his position, informed Maria that he had long sought an opportunity of opening his heart to her, and that he begged for a moment's attention.Maria closed the book and lowered her eyes, as a sign that she was listening.

"I love you," said Burmin, "I love you passionately!"Maria blushed, and bent her head still lower.

"I have behaved imprudently, yielding as I have done to the seductive pleasure of seeing and hearing you daily."Maria recollected the first letter of St.Preux in 'La Nouvelle Héloïse.'

"It is too late now to resist my fate.The remembrance of you, your dear incomparable image, must from to-day be at once the torment and the consolation of my existence.I have now a grave duty to perform, a terrible secret to disclose, which will place between us an insurmountable barrier."

"IN THE IVY BOWER."

"It has always existed!"interrupted Maria; "I could never have been your wife."

"I know," he replied quickly; "I know that you once loved.But death and three years of mourning may have worked some change.Dear, kind Maria, do not try to deprive me of my last consolation; the idea that you might have consented to make me happy if——.Don't speak, for God's sake don't speak—you torture me.Yes, I know, I feel that you could have been mine, but—I am the most miserable of beings—I am already married!"

Maria looked at him in astonishment.

"I am married," continued Burmin; "I have been married more than three years, and do not know who my wife is, or where she is, or whether I shall ever see her again."

"What are you saying?"exclaimed Maria; "how strange!Pray continue."

"In the beginning of 1812," said Burmin, "I was hurrying on to Wilna, where my regiment was stationed.Arriving one evening late at a station, I ordered, the horses to be got ready quickly, when suddenly a fearful snowstorm broke out.Both station master and drivers advised me to wait till it was over.I listened to their advice, but an unaccountable restlessness took possession of me, just as though someone was pushing me on. Meanwhile, the snowstorm did not abate. I could bear it no longer, and again ordered the horses, and started in the midst of the storm. The driver took it into his head to drive along the river, which would shorten the distance by three miles. The banks were covered with snowdrifts; the driver missed the turning which would have brought us out on to the road, and we turned up in an unknown place. The storm never ceased. I could discern a light, and told the driver to make for it. We entered a village, and found that the light proceeded from a wooden church. The church was open. Outside the railings stood several sledges, and people passing in and out through the porch."

"'Here!here!'cried several voices.I told the coachman to drive up."

"'Where have you dawdled?'said someone to me.'The bride has fainted; the priest does not know what to do: we were on the point of going back.Make haste and get out!'"

"I got out of the sledge in silence, and stepped into the church, which was dimly lighted with two or three tapers.A girl was sitting in a dark corner on a bench; and another girl was rubbing her temples.'Thank God,' said the latter, 'you have come at last!You have nearly been the death of the young lady.'"

"The old priest approached me; saying,

"'Shall I begin?'"

"'Begin—begin, reverend father,' I replied, absently."

"The young lady was raised up.I thought her rather pretty.Oh, wild, unpardonable frivolity!I placed myself by her side at the altar.The priest hurried on."

"Three men and the maid supported the bride, and occupied themselves with her alone.We were married!"

"'Kiss your wife,' said the priest."

"My wife turned her pale face towards me.I was going to kiss her, when she exclaimed, 'Oh!it is not he—not he!'and fell back insensible."

"The witnesses stared at me.I turned round and left the church without any attempt being made to stop me, threw myself into the sledge, and cried, 'Away!'"

"What!"exclaimed Maria."And you don't know what became of your unhappy wife?"

"I do not," replied Burmin; "neither do I know the name of the village where I was married, nor that of the station from which I started.At that time I thought so little of my wicked joke that, on driving away from the church, I fell asleep, and never woke till early the next morning, after reaching the third station.The servant who was with me died during the campaign, so that I have now no hope of ever discovering the unhappy woman on whom I played such a cruel trick, and who is now so cruelly avenged."

"Great heavens!"cried Maria, seizing his hand."Then it was you, and you do not recognise me?"Burmin turned pale—and threw himself at her feet.

THE UNDERTAKER.

The last remaining goods of the undertaker, Adrian Prohoroff, were piled on the hearse, and the gaunt pair, for the fourth time, dragged the vehicle along from the Basmannaia to the Nikitskaia, whither the undertaker had flitted with all his household.Closing the shop, he nailed to the gates an announcement that the house was to be sold or let, and then started on foot for his new abode.Approaching the small yellow house which had long attracted his fancy and which he at last bought at a high price, the old undertaker was surprised to find that his heart did not rejoice.Crossing the strange threshold, he found disorder inside his new abode, and sighed for the decrepit hovel, where for eighteen years everything had been kept in the most perfect order.He began scolding both his daughters and the servant for being so slow, and proceeded to help them himself.Order was speedily established.The case with the holy pictures, the cupboard with the crockery, the table, sofa, and bedstead, took up their appropriate corners in the back room. In the kitchen and parlour was placed the master's stock in trade, that is to say, coffins of every colour and of all sizes; likewise wardrobes containing mourning hats, mantles, and funeral torches. Over the gate hung a signboard representing a corpulent cupid holding a reversed torch in his hand, with the following inscription: "Here coffins are sold, covered, plain, or painted. They are also let out on hire, and old ones are repaired."

The daughters had retired to their own room, Adrian went over his residence, sat down by the window, and ordered the samovar to be got ready.

The enlightened reader is aware that both Shakespeare and Walter Scott have represented their gravediggers as lively jocular people, for the sake, no doubt, of a strong contrast.But respect for truth prevents me from following their example; and I must confess that the disposition of our undertaker corresponded closely with his melancholy trade.Adrian Prohoroff: was usually pensive and gloomy.He only broke silence to scold his daughters when he found them idle, looking out of window at the passers by, or asking too exorbitant prices for his products from those who had the misfortune (sometimes the pleasure) to require them.Sitting by the window drinking his seventh cup of tea, according to his custom, Adrian was wrapped in the saddest thoughts. He was thinking of the pouring rain, which a week before had met the funeral of a retired brigadier at the turnpike gate, causing many mantles to shrink and many hats to contract. He foresaw inevitable outlay, his existing supply of funeral apparel being in such a sad condition. But he hoped to make good the loss from the funeral of the old shopwoman, Tiruhina, who had been at the point of death for the last year. Tiruhina, however, was dying at Basgulai, and Prohoroff was afraid that her heirs, in spite of their promise to him, might be too lazy to send so far, preferring to strike a bargain with the nearest contractor.

These reflections were interrupted unexpectedly by three freemason knocks at the door."Who is there?"enquired the undertaker.The door opened and a man, in whom at a glance might be recognised a German artisan, entered the room, and with a cheery look approached the undertaker.

"Pardon me, my dear neighbour," he said, with the accent which even now we Russians never hear without a smile; "Pardon me for disturbing you; I wanted to make your acquaintance at once.I am a bootmaker, my name is Gottlieb Schultz, I live in the next street—in that little house opposite your windows.To morrow I celebrate my silver wedding, and I want you and your daughters to dine with me in a friendly way."

The invitation was accepted.The undertaker asked the bootmaker to sit down and have a cup of tea, and thanks to Gottlieb Schultz's frank disposition, they were soon talking in a friendly way.

"How does your business get on?"enquired Adrian.

"Oh, oh," replied Schultz, "one way and another I have no reason to complain.Though, of course, my goods are not like yours.A living man can do without boots, but a corpse cannot do without a coffin."

"Perfectly true," said Adrian, "still, if a living man has nothing to buy boots with he goes barefooted, whereas the destitute corpse gets his coffin sometimes for nothing."

Their conversation continued in this style for some time, until at last the bootmaker rose and took leave of the undertaker, repeating his invitation.

Next day, punctually at twelve o'clock, the undertaker and his daughters passed out at the gate of their newly-bought house, and proceeded to their neighbours.I do not intend to describe Adrian's Russian caftan nor the European dress of Akulina or Daria, contrary though this be to the custom of fiction-writers of the present day. I don't, however, think it superfluous to mention that both, maidens wore yellow bonnets and scarlet shoes, which they only did on great occasions.

The bootmaker's small lodging was filled with guests, principally German artisans, their wives, and assistants.Of Russian officials there was only one watchman, the Finn Yurko, who had managed, in spite of his humble position, to gain the special favour of his chief.He had also performed the functions of postman for about twenty-five years, serving truly and faithfully the people of Pogorelsk.The fire which, in the year 1812, consumed the capital, burnt at the same time his humble sentry box.But no sooner had the enemy fled, when in its place appeared a small, new, grey sentry box, with tiny white columns of Doric architecture, and Yurko resumed his patrol in front of it with battle-axe on shoulder, and in the civic armour of the police uniform.

He was well known to the greater portion of the German residents near the Nikitski Gates, some of whom had occasionally even passed the night from Sunday until Monday in Yurko's box.

Adrian promptly made friends with a man of whom, sooner or later, he might have need, and as the guests were just then going in to dinner they sat down together.

Mr. and Mrs. Schultz and their daughter, the seventeen-year-old Lotchen, while dining with their guests, attended to their wants and assisted the cook to wait upon them. Beer flowed. Yurko ate for four, and Adrian did not fall short of him, though his daughters stood upon ceremony.

The conversation, which was in German, grew louder every hour.

Suddenly the host called for the attention of the company, and opening a pitch-covered bottle, exclaimed loudly in Russian:

"The health of my good Louisa!"

The imitation champagne frothed.The host kissed tenderly the fresh face of his forty-year old spouse and the guests drank vociferously the health of good Louisa.

"The health of my dear guests!"cried the host opening the second bottle.The guests thanked him and emptied their glasses.Then one toast followed another.The health of each guest was proposed separately; then the health of Moscow and of about a dozen German towns.They drank the health of the guilds in general, and afterwards of each one separately; The health of the foremen and of the workmen.Adrian drank with a will and became so lively, that he himself proposed some jocular toast.

Suddenly one of the guests, a stout baker, raised his glass and exclaimed:

"The health of our customers!"

This toast like all the others was drunk joyfully and unanimously.The guests nodded to each other; the tailor to the bootmaker, the bootmaker to the tailor; the baker to them both and all to the baker.

Yurko in the midst of this bowing called out as he turned towards his neighbour:

"Now then!My friend, drink to the health of your corpses."

Everybody laughed except the undertaker, who felt himself affronted and frowned.No one noticed this; and the guests went on drinking till the bells began to ring for evening service, when they all rose from the table.

The party had broken up late and most of the guests were very hilarious.The stout baker, with the bookbinder, whose face looked as if it were bound in red morocco, led Yurko by the arms to his sentry box, thus putting in practice the proverb, "One good turns deserves another."

The undertaker went home drunk and angry.

"How, indeed," he exclaimed aloud."Is my trade worse than any other?Is an undertaker own brother to the executioner?What have the infidels to laugh at?Is an undertaker a hypocritical buffoon?I should have liked to invite them to a housewarming; to give them a grand spread.But no; that shall not be!I will ask my customers instead; my orthodox corpses."

"What!"exclaimed the servant, who at that moment was taking off the undertaker's boots."What is that, sir, you are saying?Make the sign of the cross!Invite corpses to your housewarming!How awful!"

"I will certainly invite them," persisted Adrian, "and not later than for to-morrow.Honour me, my benefactors, with your company to-morrow evening at a feast; I will offer you what God has given me."

With these words the undertaker retired to bed, and was soon snoring.

It was still dark when Adrian awoke. The shopkeeper, Triuhina, had died in the night, and her steward had sent a special messenger on horseback to inform Adrian of the fact. The undertaker gave him a grivenik [a silver fourpenny bit] for his trouble, to buy vodka with; dressed hurriedly, took an isvoshchik, and drove off to Rasgulai.At the gate of the dead woman's house the police were already standing, and dealers in mourning goods were hovering around, like ravens who have scented a corpse.The defunct was lying in state on the table, yellow like wax, but not yet disfigured by decomposition.Hear her, in a crowd, were relations, friends, and domestics.All the windows were open; wax tapers were burning; and the clergy were reading prayers.Adrian went up to the nephew, a young shopman in a fashionable surtout, and informed him that the coffin, tapers, pall, and the funeral paraphernalia in general would promptly arrive.The heir thanked him in an absent manner, saying that he would not bargain about the price, but leave it all to his conscience.The undertaker, as usual, vowed that his charges should be moderate, exchanged significant glances with the steward, and left to make the necessary preparations.

The whole day was spent in travelling from Rasgulai to the Nikitski Grates and back again. Towards evening everything was settled, and he started home on foot after discharging his hired isvoshchik. It was a moonlight night, and the undertaker got safely to the Nikitski Grates. At Yosnessenia he met our acquaintance, Yurko, who, recognising the undertaker, wished him good-night. It was late. The undertaker was close to his house when he thought he saw some one approach the gates, open the wicket, and go in.

"What does it mean?"thought Adrian."Who can be wanting me again?Is it a burglar, or can my foolish girls have lovers coming after them?There is no telling," and the undertaker was on the point of calling his friend Yurko to his assistance, when some one else came up to the wicket and was about to enter, but seeing the master of the house run towards him, he stopped, and took off his three cornered hat.His face seemed familiar to Adrian, but in his hurry he had not been able to see it properly.

"You want me?"said Adrian, out of breath."Walk in, if you please."

"Don't stand on ceremony, my friend," replied the other, in a hollow voice, "go first, and show your guest the way."

Adrian had no time to waste on formality.The gate was open, and he went up to the steps followed by the other.Adrian heard people walking about in his rooms.

"What the devil is this?"he wondered, and he hastened to see.But now his legs seemed to be giving way.The room was full of corpses.The moon, shining through the windows, lit up their yellow and blue faces, sunken mouths, dim, half-closed eyes, and protruding noses.To his horror, Adrian recognised in them people he had buried, and in the guest who came in with him, the brigadier who had been interred during a pouring rain.They all, ladies and gentlemen, surrounded the undertaker, bowing and greeting him affably, except one poor fellow lately buried gratis, who, ashamed of his rags, kept at a distance in a corner of the room.The others were all decently clad; the female corpses in caps and ribbons, the soldiers and officials in their uniforms, but with unshaven beards; and the tradespeople in their best caftans.

"Prohoroff," said the brigadier, speaking on behalf of all the company, "we have all risen to profit by your invitation. Only those have stopped at home who were quite unable to do otherwise; who have crumbled away and have nothing left but bare bones. Even among those there was one who could not resist—he wanted so much to come."

At this moment a diminutive skeleton pushed his way through the crowd and approached Adrian.His death's head grinned affably at the undertaker.Shreds of green and red cloth and of rotten linen hung on him as on a pole; while the bones of his feet clattered inside his heavy boots like pestles in mortars.

"You do not recognise me, Prohoroff?"said the skeleton."Don't you remember the retired, sergeant in the guards, Peter Petrovitch Kurilkin, him to whom you in the year 1799 sold your first coffin, and of deal instead of oak?"With these words the corpse stretched out his long arms to embrace him.But Adrian collecting his strength, shrieked, and pushed him away.Peter Petrovitch staggered, fell over, and crumbled to pieces.There was a murmur of indignation among the company of corpses.All stood up for the honour of their companion, threatening and abusing Adrian till the poor man, deafened by their shrieks and quite overcome, lost his senses and fell unconscious among the bones of the retired sergeant of the guard.

The sun had been shining for sometime upon the bed on which the undertaker lay, when he at last opened his eyes and saw the servant lighting the samovar. With horror he recalled all the incidents of the previous day. Triuchin, the brigadier, and the sergeant, Kurilkin, passed dimly before his imagination. He waited in silence for the servant to speak and tell him what had occurred during the night.

"How you have slept, Adrian Prohorovitch!"said Aksima, handing him his dressing-gown."Your neighbour the tailor called, also the watchman, to say that to-day was Turko's namesday; but you were so fast asleep that we did not disturb you."

"Did anyone come from the late Triuhina?"

"The late?Is she dead, then?"

"What a fool!Didn't you help me yesterday to make arrangements for her funeral?"

"Oh, my batiushka! [little father] are you mad, or are you still suffering from last night's drink? You were feasting all day at the German's. You came home drunk, threw yourself on the bed, and and have slept till now, when the bells have stopped ringing for Mass."

"Really!"exclaimed the undertaker, delighted at the explanation.

"Of course," replied the servant.

"Well, if that is the case, let us have tea quickly, and call my daughters."

THE POSTMASTER.

Who has not cursed the Postmaster; who has not quarrelled with him? Who, in a moment of anger, has not demanded the fatal hook to write his ineffectual complaint against extortion, rudeness, and unpunctuality? Who does not consider him a human monster, equal only to our extinct attorney, or, at least, to the brigands of the Murom Woods? Let us, however, be just and place ourselves in his position, and, perhaps, we shall judge him less severely. What is a Postmaster? A real martyr of the 14th class (i.e. , of nobility), only protected by his tchin (rank) from personal violence; and that not always. I appeal to the conscience of my readers. What is the position of this dictator, as Prince Yiasemsky jokingly calls him? Is it not really that of a galley slave? No rest for him day or night. All the irritation accumulated in the course of a dull journey by the traveller is vented upon the Postmaster. If the weather is intolerable, the road wretched, the driver obstinate, or the horses intractable—the Postmaster is to blame. Entering his humble abode, the traveller looks upon him as his enemy, and the Postmaster is lucky if he gets rid of his uninvited guest soon. But should there happen to be no horses! Heavens! what abuse, what threats are showered upon his head! Through rain and mud he is obliged to seek them, so that during a storm, or in the winter frosts, he is often glad to take refuge in the cold passage in order to snatch a few moments of repose and to escape from the shrieking and pushing of irritated guests.

If a general arrives, the trembling Postmaster supplies him with the two last remaining troiki (team of three horses abreast), of which one troika ought, perhaps, to have been reserved for the diligence. The general drives on without even a word of thanks. Five minutes later the Postmaster hears—a bell! and the guard throws down his travelling certificate on the table before him! Let us realize all this, and, instead of anger, we shall feel sincere pity for the Postmaster. A few words more. In the course of twenty years I have travelled all over Russia, and know nearly all the mail routes. I have made the acquaintance of several generations of drivers. There are few postmasters whom I do not know personally, and few with whom I have not had dealings. My curious collection of travelling experiences I hope shortly to publish. At present I will only say that, as a class, the Postmaster is presented to the public in a false light. This much-libelled personage is generally a peaceful, obliging, sociable, modest man, and not too fond of money. From his conversation (which the travelling gentry very wrongly despise) much interesting and instructive information may be acquired. As far as I am concerned, I profess that I prefer his talk to that of some tchinovnik (official) of the 6th class, travelling for the Government.

It may easily be guessed that I have some friends among the honourable class of postmasters.Indeed, the memory of one of them is very dear to me.Circumstances at one time brought us together, and it is of him that I now intend to tell my dear readers.

In the May of 1816 I chanced to be passing through the Government of ----, along a road now no longer existing. I held a small rank, and was travelling with relays of three horses while paying only for two. Consequently the Postmaster stood upon no ceremony with me, but I had often to take from him by force what I considered to be mine by right. Being young and passionate, I was indignant at the meanness and, cowardice of the Postmaster when he handed over the troika prepared for me to some official gentleman of higher rank.

It also took me a long time to get over the offence, when a servant, fond of making distinctions, missed me when waiting at the governor's table.Now the one and the other appear to me to be quite in the natural course of things.Indeed, what would become of us, if, instead of the convenient rule that rank gives precedence to rank, the rule were to be reversed, and mind made to give precedence to mind?What disputes would arise!Besides, to whom would the attendants first hand the dishes?But to return to my story.

The day was hot.About three versts from the station it began to spit, and a minute afterwards there was a pouring rain, and I was soon drenched to the skin.Arriving at the station, my first care was to change my clothes, and then I asked for a cup of tea.

"Hi! Dunia!" called out the Postmaster, "Prepare the samovar and fetch some cream."

In obedience to this command, a girl of fourteen appeared from behind the partition, and ran out into the passage.I was struck by her beauty.

"Is that your daughter?"I inquired of the Postmaster.

"Yes," he answered, with a look of gratified pride, "and such a good, clever girl, just like her late mother."Then, while he took note of my travelling certificate, I occupied the time in examining the pictures which decorated the walls of his humble abode. They were illustrations of the story of the Prodigal Son. In the firsts a venerable old man in a skull cap and dressing gown, is wishing good-bye to the restless youth who naturally receives his blessing and a bag of money. In another, the dissipated life of the young man is painted in glaring colours; he is sitting at a table surrounded by false friends and shameless women. In the next picture, the ruined youth in his shirt sleeves and a three-corned hat, is taking care of some swine while sharing their food. His face expresses deep sorrow and contrition. Finally, there was the representation of his return to his father. The kind old man, in the same cap and dressing gown, runs out to meet him; the prodigal son falls on his knees before him; in the distance, the cook is killing the fatted calf, and the eldest son is asking the servants the reason of all this rejoicing. At the foot of each picture I read some appropriate German verses. I remember them all distinctly, as well as some pots of balsams, the bed with the speckled curtains, and many other characteristic surroundings. I can see the stationmaster at this moment; a man about fifty years of age, fresh and strong, in a long green coat, with three medals on faded ribbons.

I had scarcely time to settle with my old driver when Dunia returned with the samovarThe little coquette saw at a second glance the impression she had produced upon me. She lowered her large, blue eyes. I spoke to her, and she replied confidently, like a girl accustomed to society. I offered a glass of punch to her father, to Dunia I handed a cup of tea. Then we all three fell into easy conversation, as if we had known each other all our lives.

The horses had been waiting a long while, but I was loth to part from the Postmaster and his daughter. At last I took leave of them, the father wishing me a pleasant journey, while the daughter saw me to the telegaIn the corridor I stopped and asked permission to kiss her.Dunia consented.I can remember a great many kisses since then, but none which left such a lasting, such a delightful impression.

Several years passed, when circumstances brought me back to the same tract, to the very same places.I recollected the old Postmasters daughter, and rejoiced at the prospect of seeing her again.

"But," I thought, "perhaps the old Postmaster has been changed, and Dunia may be already married."The idea that one or the other might be dead also passed through my mind, and I approached the station of ---- with sad presentiments.The horses drew up at the small station house.I entered the waiting-room, and instantly recognised the pictures representing the story of the Prodigal Son. The table and the bed stood in their old places, but the flowers on the window sills had disappeared, while all the surroundings showed neglect and decay.

The Postmaster was asleep under his great-coat, but my arrival awoke him and he rose.It was certainly Simeon Virin, but how aged!While he was preparing to make a copy of my travelling certificate, I looked at his grey hairs, and the deep wrinkles in his long, unshaven face, his bent back, and I was amazed to see how three or four years had managed to change a strong, middle-aged man into a frail, old one.

"Do you recognise me?"I asked him, "we are old friends."

"May be," he replied, gloomily, "this is a highway, and many travellers have passed through here."

"Is your Dunia well?"I added.The old man frowned.

"Heaven knows," he answered.

"Apparently, she is married," I said.

The old man pretended not to hear my question, and in a low voice went on reading my travelling certificate.I ceased my inquiries and ordered hot water.

My curiosity was becoming painful, and I hoped that the punch would loosen the tongue of my old friend. I was not mistaken; the old man did not refuse the proffered tumbler. I noticed that the rum dispelled his gloom. At the second glass he became talkative, remembered, or at any rate looked as if he remembered, me, and I heard the story, which at the time interested me and even affected me much.

"So you knew my Dunia?"he began."But, then, who did not?Oh, Dunia, Dunia!What a beautiful girl you were!You were admired and praised by every traveller.No one had a word to say against her.The ladies gave her presents—one a handkerchief, another a pair of earrings.The gentlemen stopped on purpose, as if to dine or to take supper, but really only to take a longer look at her.However rough a man might be, he became subdued in her presence and spoke graciously to me.Will you believe me, sir?Couriers and special messengers would talk to her for half-an-hour at the time.She was the support of the house.She kept everything in order, did everything and looked after everything.While I, the old fool that I was, could not see enough of her, or pet her sufficiently.How I loved her!How I indulged my child!Surely her life was a happy one?But, no!fate is not to be avoided."

Then he began to tell me his sorrow in detail.Three years before, one winter evening, while the Postmaster was ruling a new book, his daughter in the next partition was busy making herself a dress, when a troika drove up and a traveller, wearing a Circassian hat and a long military overcoat, and muffled in a shawl, entered the room and demanded horses.

The horses were all out.Hearing this, the traveller had raised his voice and his whip, when Dunia, accustomed to such scenes, rushed out from behind the partition and inquired pleasantly whether he would not like something to eat?Her appearance produced the usual effect.The passenger's rage subsided, he agreed to wait for horses, and ordered some supper.He took off his wet hat, unloosed the shawl, and divested himself of his long overcoat.

The traveller was a tall, young hussar with a small black moustache. He settled down comfortably at the Postmaster's and began a lively, conversation with him and his daughter. Supper was served. Meanwhile, the horses returned and the Postmaster ordered them instantly, without being fed, to be harnessed to the traveller's kibitka. But returning to the room, he found the young man senseless on the bench where he lay in a faint. Such a headache had attacked him that it was impossible for him to continue his journey. What was to be done? The Postmaster gave up his own bed to him; and it was arranged that if the patient was not better the next morning to send to C——— for the doctor.

Next day the hussar was worse.His servant rode to the town to fetch the doctor.Dunia bound up his head with a handkerchief moistened in vinegar, and sat down with her needlework by his bedside.In the presence of the Postmaster the invalid groaned and scarcely said a word.

Nevertheless, he drank two cups of coffee and, still groaning, ordered a good dinner.Dunia never left him.Every time he asked for a drink Dunia handed him the jug of lemonade prepared by herself.After moistening his lips, the patient each time he returned the jug gave her hand a gentle pressure in token of gratitude.

Towards dinner time the doctor arrived.He felt the patient's pulse, spoke to him in German and in Russian, declared that all he required was rest, and said that in a couple of days he would be able to start on his journey.The hussar handed him twenty-five rubles for his visit, and gave him an invitation to dinner, which the doctor accepted.They both ate with a good appetite, and drank a bottle of wine between them.Then, very pleased with one another, they separated.

Another day passed, and the hussar had quite recovered.He became very lively, incessantly joking, first with Dunia, then with the Postmaster, whistling tunes, conversing with the passengers, copying their travelling certificates into the station book, and so ingratiating himself that on the third day the good Postmaster regretted parting with his dear lodger.

It was Sunday, and Dunia was getting ready to attend mass. The hussar's kibitka was at the door. He took leave of the Postmaster, after recompensing him handsomely for his board and lodging, wished Dunia good-bye, and proposed to drop her at the church, which was situated at the other end of the village. Dunia hesitated.

"What are you afraid of?"asked her father."His nobility is not a wolf.He won't eat you.Drive with him as far as the church."

Dunia got into the carriage by the side of the hussar.The servant jumped on the coach box, the coachman gave a whistle, and the horses went off at a gallop.

The poor Postmaster could not understand how he came to allow his Dunia to drive off with the hussar; how he could have been so blind, and what had become of his senses.Before half-an-hour had passed his heart misgave him.It ached, and he became so uneasy that he could bear the situation no longer, and started for the church himself.Approaching the church, he saw that the people were already dispersing.But Dunia was neither in the churchyard nor at the entrance.He hurried into the church; the priest was just leaving the altar, the clerk was extinguishing the tapers, two old women were still praying in a corner; but Dunia was nowhere to be seen. The poor father could scarcely summon courage to ask the clerk if she had been to mass. The clerk replied that she had not. The Postmaster returned home neither dead nor alive. He had only one hope left; that Dunia in the flightiness of her youth had, perhaps, resolved to drive as far as the next station, where her godmother lived. In patient agitation he awaited the return of the troika with which he had allowed her to drive off, but the driver did not come back. At last, towards night, he arrived alone and tipsy, with the fatal news that Dunia had gone on with the hussar.

The old man succumbed to his misfortune, and took to his bed, the same bed where, the day before, the young impostor had lain.Recalling all the circumstances, the Postmaster understood now that the hussar's illness had been shammed.The poor fellow sickened with severe fever, he was removed to C———, and in his place another man was temporarily appointed.The same doctor who had visited the hussar attended him.He assured the Postmaster that the young man had been perfectly well, that he had from the first had suspicions of his evil intentions, but that he had kept silent for fear of his whip.

Whether the German doctor spoke the truth, or was anxious only to prove his great penetration, his assurance brought no consolation to the poor patient.As soon as he was beginning to recover from his illness, the old Postmaster asked his superior postmaster of the town of C——— for two months' leave of absence, and without saying a word to anyone, he started off on foot to look for his daughter.

From the station book he discovered that Captain Minsky had left Smolensk for Petersburg.The coachman who drove him said that Dunia had wept all the way, though she seemed to be going of her own free will.

"Perhaps," thought the station master, "I shall bring back my strayed lamb."With this idea he reached St.Petersburg, and stopped with the Ismailovsky regiment, in the quarters of a non-commissioned officer, his old comrade in arms. Beginning his search he soon found out that Captain Minsky was in Petersburg, living at Demuth's Hotel.The Postmaster determined to see him.

Early in the morning he went to Minsky's antechamber, and asked to have his nobility informed that an old soldier wished to see him.The military attendant, in the act of cleaning a boot on a boot-tree, informed him that his master was asleep, and never received anyone before eleven o'clock.The Postmaster left to return at the appointed time. Minsky came out to him in his dressing gown and red skull cap.

"Well, my friend, what do you want?"he inquired.

The old maids heart boiled, tears started to his eyes, and in a trembling voice he could only say, "Your nobility; be divinely merciful!"

Minsky glanced quickly at him, flushed, and seizing him by the hand, led him into his study and locked the door.

"Your nobility!"continued the old man, "what has fallen from the cart is lost; give me back, at any rate, my Dunia.Let her go.Do not ruin her entirely."

"What is done cannot be undone," replied the young man, in extreme confusion."I am guilty before you, and ready to ask your pardon.But do not imagine that I could neglect Dunia.She shall be happy, I give you my word of honour.Why do you want her?She loves me; she has forsaken her former existence.Neither you nor she can forget what has happened."Then, pushing something up his sleeve, he opened the door, and the Postmaster found himself, he knew not how, in the street.

He stood long motionless, at last catching sight of a roll of papers inside his cuff, he pulled them out and unrolled several crumpled-up fifty ruble notes.His eyes again filled with tears, tears of indignation! He crushed the notes into a ball, threw them on the ground, and, stamping on them with his heel, walked away. After a few steps he stopped, reflected a moment, and turned back.

But the notes were gone. A well-dressed young man, who had observed him, ran towards an isvoshtchick, got in hurriedly, and called to the driver to be "off."

The Postmaster did not pursue him.He had resolved to return home to his post-house; but before doing so he wished to see his poor Dunia once more.With this view, a couple of days afterwards he returned to Minsky's lodgings.But the military servant told him roughly that his master received nobody, pushed him out of the antechamber, and slammed the door in his face.The Postmaster stood and stood, and at last went away.

That same day, in the evening, he was walking along the Leteinaia, having been to service at the Church of the All Saints, when a smart drojki flew past him, and in it the Postmaster recognised Minsky. The drojki stopped in front of a three-storeyed house at the very entrance, and the hussar ran up the steps. A happy thought occurred to the Postmaster. He retraced his steps.

"Whose horses are these?"he inquired of the coachman."Don't they belong to Minsky?"

"Exactly so," replied the coachman."Why do you ask?"

"Why!your master told me to deliver a note for him to his Dunia, and I have forgotten where his Dunia lives."

"She lives here on the second floor; but you are too late, my friend, with your note; he is there himself now."

"No matter," answered the Postmaster, who had an undefinable sensation at his heart."Thanks for your information; I shall be able to manage my business."With these words he ascended the steps.

The door was locked; he rang.There were several seconds of painful delay.Then the key jingled, and the door opened.

"Does Avdotia Simeonovna live here?"he inquired.

"She does," replied the young maid-servant, "What do you want with her?"

The Postmaster did not reply, but walked on.

"You must not, must not," she called after him; "Avdotia Simeonovna has visitors."But the Postmaster, without listening, went on.The first two rooms were dark.In the third there was a light.He approached the open door and stopped.In the room, which was beautifully furnished, sat Minsky in deep thought.Dunia, dressed in all the splendour of the latest fashion, sat on the arm of his easy chair, like a rider on an English side saddle. She was looking tenderly at Minsky, while twisting his black locks round her glittering fingers. Poor Postmaster! His daughter had never before seemed so beautiful to him. In spite of himself, he stood admiring her.

"Who is there?"she asked, without raising her head.

He was silent.

Receiving no reply Dunia looked up, and with a cry she fell on the carpet.

Minsky, in alarm, rushed to pick her up, when suddenly seeing the old Postmaster in the doorway, he left Dunia and approached him, trembling with rage.

"What do you want?"he inquired, clenching his teeth."Why do you steal after me everywhere, like a burglar?Or do you want to murder me?Begone!"and with a strong hand he seized the old man by the scruff of the neck and pushed him down the stairs.

The old man went back to his rooms. His friend advised him to take proceedings, but the Postmaster reflected, waved his hand, and decided to give the matter up.Two days afterwards he left Petersburg for his station and resumed his duties.

"This is the third year," he concluded, "that I am living without my Dunia; and I have had no tidings whatever of her.Whether she is alive or not God knows. Many tilings happen. She is not the first, nor the last, whom a wandering blackguard has enticed away, kept for a time, and then dropped. There are many such young fools in Petersburg to-day, in satins and velvets, and to-morrow you see them sweeping the streets in the company of drunkards in rags. When I think sometimes that Dunia, too, may end in the same way, then, in spite of myself, I sin, and wish her in her grave."

Such was the story of my friend, the old Postmaster, the story more than once interrupted by tears, which he wiped away picturesquely with the flap of his coat like the faithful Terentieff in Dmitrieff's beautiful ballad.The tears were partly caused by punch, of which he had consumed five tumblers in the course of his narrative.But whatever their origin, I was deeply affected by them.After parting with him, it was long before I could forget the old Postmaster, and I thought long of poor Dunia.

Lately, again passing through the small place of ———, I remembered my friend.I heard that the station over which he ruled had been done away with.To my inquiry, "Is the Postmaster alive?"no one could give a satisfactory answer.Having resolved to pay a visit to the familiar place, I hired horses of my own, and started for the village of N——.

It was autumn.Grey clouds covered the sky; a cold wind blew from the close reaped fields, carrying with it the brown and yellow leaves of the trees which it met.I arrived in the village at sunset, and stopped at the station house.In the passage (where once Dunia had kissed me) a stout woman met me; and to my inquiries, replied that the old Postmaster had died about a year before; that a brewer occupied his house; and that she was the wife of that brewer.I regretted my fruitless journey, and my seven roubles of useless expense.

"Of what did he die?"I asked the brewer's wife.

"Of drink," she answered.

"And where is he buried?"

"Beyond the village, by the side of his late wife."

"Could someone take me to his grave?"

"Certainly!Hi, Vanka!cease playing with the cat and take this gentleman to the cemetery, and show him the Postmaster's grave."

At these words, a ragged boy, with red hair and a squint, ran towards me to lead the way.

"Did you know the poor man?"I asked him, on the road.

"How should I not know him? He taught me to make whistles. When (may he be in heaven!) we met him coming from the tavern, we used to run after him calling, 'Daddy! daddy! some nuts,' and he gave us nuts. He idled most of his time away with, us."

"And do the travellers ever speak of him?"

"There are few travellers now-a-days, unless the assize judge turns up; and he is too busy to think of the dead.But a lady, passing through last summer, did ask after the old Postmaster, and she went to his grave."

"What was the ladylike?"I inquired curiously.

"A beautiful lady," answered the boy. "She travelled in a coach with six horses, three beautiful little children, a nurse, and a little black dog; and when she heard that the old Postmaster was dead, she wept, and told the children to keep quiet while she went to the cemetery. I offered to show her the way, but the lady said, 'I know the way,' and she gave me a silver piatak (twopence) ... such a kind lady!"

We reached the cemetery.It was a bare place unenclosed, marked with wooden crosses and unshaded by a single tree.Never before had I seen such a melancholy cemetery.

"Here is the grave of the old Postmaster," said the boy to me, as he pointed to a heap of sand into which had been stuck a black cross with a brass icon (image).

"Did the lady come here?"I asked.

"She did," replied Vanka."I saw her from a distance.She lay down here, and remained lying down for a long while. Then she went into the village and saw the priest. She gave him some money and drove off. To me she gave a silver piatak. She was a splendid lady!"

And I also gave the boy a silver piatak, regretting neither the journey nor the seven roubles that it had cost me.

THE LADY RUSTIC.

In one of our distant provinces was the estate of Ivan Petrovitch Berestoff. As a youth he served in the guards, but having left the army early in 1797 he retired to his country seat and there remained. He married a wife from among the poor nobility, and when she died in childbed he happened to be detained on farming business in one of his distant fields. His daily occupations soon brought him consolation. He built a house on his own plan, set up his own cloth factory, became his own auditor and accountant, and began to think himself the cleverest fellow in the whole district. The neighbours who used to come to him upon a visit and bring their families and dogs took good care not to contradict him. His work-a-day dress was a short coat of velveteen; on holidays he wore a frock-coat of cloth from his own factory. His accounts took most of his time, and he read nothing but the Senatorial NewsOn the whole, though he was considered proud, he was not disliked. The only person who could never get on with him was his nearest neighbour, Grigori Ivanovitch Muromsky. A true Russian barin, he had squandered in Moscow a large part of his estate, and having lost his wife as well as his money he had retired to his sole remaining property, and there continued his extragavance but in a different way. He set up an English garden on which he spent nearly all the income he had left. His grooms wore English liveries. An English governess taught his daughter. He farmed his land upon the English system. But foreign farming grows no Russian corn.

So, in spite of his retirement, the income of Grigori Ivanovitch did not increase.Even in the country he had a faculty for making new debts.But he was no fool, people said, for was he not the first landowner in all that province to mortgage his property to the government—a process then generally believed to be one of great complexity and risk?Among his detractors Berestoff, a thorough hater of innovation, was the most severe.In speaking of his neighbour's Anglo-mania he could scarcely keep his feelings under control, and missed no opportunity for criticism.To some compliment from a visitor to his estate he would answer, with a knowing smile:

"Yes, my farming is not like that of Grigori Ivanovitch.I can't afford to ruin my land on the English system, but I am satisfied to escape starvation on the Russian."

Obliging neighbours reported these and other jokes to Grigori, with additions and commentaries of their own.The Anglo-maniac was as irritable as a journalist under this criticism, and wrathfully referred to his critic as a bumpkin and a bear.

Relations were thus strained when Berestoff's son came home.Having finished his university career, he wanted to go into the army; but his father objected.For the civil service young Berestoff had no taste.Neither would yield, so young Alexis took up the life of a country gentleman, and to be ready for emergencies cultivated a moustache.He was really a handsome fellow, and it would indeed have been a pity never to pinch his fine figure into a military uniform, and instead of displaying his broad shoulders on horseback to round them over an office desk.Ever foremost in the hunting-field, and a straight rider, it was quite clear, declared the neighbours, that he could never make a good official.The shy young ladies glanced and the bold stared at him in admiration; but he took no notice of them, and each could only attribute his indifference to some prior attachment.In fact, there was in private circulation, copied from an envelope in his handwriting, this address:

A. N. P. ,

Care of Akulina Petrovna Kurotchkina,

Opposite Alexeieff Monastery.

Those readers who have not seen our country life can hardly realize the charm of these provincial girls.Breathing pure air under the shadow of their apple trees, their only knowledge of the world is drawn from books.In solitude and unrestrained, their feelings and their passions develop early to a degree unknown to the busier beauties of our towns.For them the tinkling of a bell is an event, a drive into the nearest town an epoch, and a chance visit a long, sometimes an everlasting remembrance.At their oddities he may laugh who will, but superficial sneers cannot impair their real merits—their individuality, which, so says Jean Paul, is a necessary element of greatness.The women in large towns may be better educated, but the levelling influence of the world soon makes all women as much alike as their own head-dresses.

Let not this be regarded as condemnation. Still as an ancient writer says nota nostra manet.

It may be imagined what an impression Alexis made on our country misses.He was the first gloomy and disenchanted hero they had ever beheld; the first who ever spoke to them of vanished joys and blighted past.Besides, he wore a black ring with a death's head on it.All this was quite a new thing in that province, and the young ladies all went crazy.

But she in whose thoughts he dwelt most deeply was Lisa, or, as the old Anglo-maniac called her, Betty, the daughter of Grigori Ivanovitch.Their fathers did not visit, so she had never seen Alexis, who was the sole topic of conversation among her young neighbours.She was just seventeen, with dark eyes lighting up her pretty face.An only, and consequently a spoilt child, full of life and mischief, she was the delight of her father, and the distraction of her governess, Miss Jackson, a prim spinster in the forties, who powdered her face and blackened her eyebrows, read Pamela twice a year, drew a salary of 2,000 rubles, and was nearly bored to death in barbarous Russia.

Lisa's maid Nastia was older, but quite as flighty as her mistress, who was very fond of her, and had her as confidante in all her secrets and as fellow-conspirator in her mischief.

In fact, no leading lady played half such an important part in French tragedy as was played by Nastia in the village.

Said Nastia, while dressing her young lady:

"May I go to-day and visit a friend?"

"Yes.Where?"

"To the Berestoff's.It is the cook's namesday.He called yesterday to ask us to dinner."

"Then," said Lisa, "the masters quarrel and the servants entertain one another."

"And what does that matter to us?"said Nastia."I belong to you and not to your father.You have not quarrelled with young Berestoff yet.Let the old people fight if they please."

"Nastia!try and see Alexei Berestoff.Come back and tell me all about him."

Nastia promised; Lisa spent the whole day impatiently waiting for her.In the evening she returned.

"Well, Lisaveta Grigorievna!"she said, as she entered the room.

"I have seen young Berestoff.I had a good look at him.We spent the whole day together."

"How so?tell me all about it."

"Certainly?We started, I and Anissia——"

"Yes, yes, I know!What then?"

"I would rather tell you in proper order.We were just in time for dinner; the room was quite full.There were the Zaharievskys, the steward's wife and daughters, the Shlupinskys——"

"Yes, yes!And Berestoff?"

"Wait a bit.We sat down to dinner.The steward's wife had the seat of honour; I sat next to her, and her daughters were huffy; but what do I care!"

"Oh, Nastia!How tiresome you are with these everlasting details!"

"How impatient you are!Well, then we rose from table—we had been sitting for about three hours and it was a splendid dinner-party, blue, red and striped creams—then we went into the garden to play at kiss-in-the-ring when the young gentleman appeared."

"Well, is it true?Is he so handsome?"

"Wonderfully handsome!I may say beautiful.Tall, stately, with a lovely colour."

"Really!I thought his face was pale.Well, how did he strike you—Was he melancholy and thoughtful?"

"Oh, no!I never saw such a mad fellow.He took it into his head to join us at kiss-in-the-ring.""He played at kiss-in-the-ring!It is impossible."

"No, it's very possible; and what more do you think?When he caught any one he kissed her.""Of course you may tell lies if you like, Nastia."

"As you please, miss, only I am not lying.I could scarcely get away from him.Indeed he spent the whole day with us."

"Why do people say then that he is in love and looks at nobody?"

"I am sure I don't know, miss.He looked too much at me and Tania too, the steward's daughter, and at Pasha too.In fact, he neglected nobody.He is such a wild fellow!"

"This is surprising; and what do the servants say about him?"

"They say he is a splendid gentleman—so kind, so lively!He has only one fault: he is too fond of the girls.But I don't think that is such a great fault.He will get steadier in time."

"How I should like to see him," said Lisa, with a sigh.

"And why can't you?Tugilovo is only a mile off.Take a walk in that direction, or a ride, and you are sure to meet him.He shoulders his gun and goes shooting every morning."

"No, it would never do.He would think I was running after him.Besides, our fathers have quarrelled, so he and I could hardly set up a friendship.Oh, Nastia!I know what I'll do.I will dress up like a peasant."

"That will do. Put on a coarse chemise and a sarafan, and set out boldly for Tugilovo.Berestoff will never miss you I promise you."

"I can talk like a peasant splendidly. Oh, Nastia, dear Nastia, what a happy thought!" and Lisa went to bed resolved to carry out her plan. Next day she made her preparations. She went to the market for some coarse linen, some dark blue stuff, and some brass buttons, and out of these Nastia and she cut a chemise and a sarafan. All the maid-servants were set down to sew, and by evening everything was ready.

As she tried on her new costume before the glass, Lisa said to herself that she had never looked so nice. Then she began to rehearse her meeting with Alexis. First she gave him a low bow as she passed along, then she continued to nod her head like a mandarin. Next she addressed him in a peasant patois, simpering and shyly hiding her face behind her sleeve. Nastia gave the performance her full approval. But there was one difficulty. She tried to cross the yard barefooted, but the grass stalks pricked her tender feet and the gravel caused intolerable pain. Nastia again came to the rescue.

She took the measure of Lisa's foot and hurried across the fields to the herdsman Trophim, of whom she ordered a pair of bark shoes.

The next morning before daylight Lisa awoke.The whole household was still asleep.Nastia was at the gate waiting for the herdsman; soon the sound of his horn drew near, and the village herd straggled past the Manor gates.After them came Trophim, who, as he passed, handed to Nastia a little pair of speckled bark shoes, and received a ruble.

Lisa, who had quietly donned her peasant dress, whispered to Nastia her last instructions about Miss Jackson; then she went through the kitchen, out of the back door, into the open field, then she began to run.

Dawn was breaking, and the rows of golden clouds stood like courtiers waiting for their monarch.The clear sky, the fresh morning air, the dew, the breeze and singing of the birds filled Lisa's heart with child-like joy.

Fearing to meet with some acquaintance, she did nor walk but flew.As she drew near the wood where lay the boundary of her father's property she slackened her pace.It was here she was to meet Alexis.Her heart beat violently, she knew not why.The terrors of our youthful escapades are their chief charm.

Lisa stepped forward into the darkness of the wood; its hollow echoes bade her welcome.Her buoyant spirits gradually gave place to meditation.She thought—but who shall truly tell the thoughts of sweet seventeen in a wood, alone, at six o'clock on a spring morning?

And as she walked in meditation under the shade of lofty trees, suddenly a beautiful pointer began to bark at her.Lisa cried out with fear, and at the same moment a voice exclaimed, "Tout beau Shogar, ici," and a young sportsman stepped from behind the bushes."Don't be afraid, my dear, he won't bite."

Lisa had already recovered from her fright, and instantly took advantage of the situation.

"It's all very well, sir," she said, with assumed timidity and shyness, "I am afraid of him, he seems such a savage creature, and may fly at me again."

Alexis, whom the reader has already recognised, looked steadily at the young peasant."I will escort you, if you are afraid; will you allow me to walk by your side?"

"Who is to prevent you?"replied Lisa."A freeman can do as he likes, and the road is public!"

"Where do you come from?"

"From Prilutchina; I am the daughter of Yassili, the blacksmith, and I am looking for mushrooms." She was carrying a basket suspended from her shoulders by a cord.

"And you, barin; are you from Tugilovo?"

"Exactly, I am the young gentleman's valet" (he wished to equalize their ranks).But Lisa looked at him and laughed.

"Ah!you are lying," she said."I am not a fool.I see you are the master himself."

"What makes you think so?"

"Everything."

"Still——?"

"How can one help it.You are not dressed like a servant.You speak differently.You even call your dog in a foreign tongue."

Lisa charmed him more and more every moment.Accustomed to be unceremonious with pretty country girls, he tried to kiss her, but Lisa jumped aside, and suddenly assumed so distant and severe an air that though it amused him he did not attempt any further familiarities.

"If you wish to remain friends," she said, with dignity, "do not forget yourself."

"Who has taught you this wisdom?"asked Alexis, with a laugh."Can it be my little friend Nastia, your mistress's maid?So this is how civilization spreads."

Lisa felt she had almost betrayed herself, and said, "Do you think I have never been up to the Manor House? I have seen and heard more than you think. Still, chattering here with you won't get me mushrooms. You go that way, barin; I'll go the other, begging your pardon;" and Lisa made as if to depart, but Alexis held her by the hand.

"What is your name, my dear?"

"Akulina," she said, struggling to get her fingers free. "Let me go, barin, it is time for me to be home."

"Well, my friend Akulina, I shall certainly call on your father, Yassili, the blacksmith."

"For the Lord's sake don't do that. If they knew at home I had been talking here alone with the young barin, I should catch it. My father would beat me within an inch of my life."

"Well, I must see you again."

"I will come again some other day for mushrooms."

"When?"

"To-morrow, if you like."

"My dear Akulina, I would kiss you if I dared.To-morrow, then, at the same time; that is a bargain."

"All right."

"You will not play me false?"

"No."

"Swear it."

"By the Holy Friday, then, I will come."

The young couple parted. Lisa ran out of the wood across the fields, stole into the garden, and rushed headlong into the farmyard, where Nastia was waiting for her. Then she changed her dress, answering at random the impatient questions of her confidante, and went into the dining-room to find the cloth laid and breakfast ready.Miss Jackson, freshly powdered and Jaced, until she looked like a wine glass, was cutting thin slices of bread and butter.Her father complimented Lisa on her early walk.

"There is no healthier habit," he remarked, "than to rise at daybreak."He quoted from the English papers several cases of longevity, adding that all centenarians had abstained from spirits, and made it a practice to rise at daybreak winter and summer.Lisa did not prove an attentive listener.She was repeating in her mind the details of her morning's interview, and as she recalled Akulina's conversation with the young sportsman her conscience smote her. In vain she assured herself that the bounds of decorum had not been passed. This joke, she argued, could have no evil consequences, but conscience would not be quieted. What most disturbed her was her promise to repeat the meeting. She half decided not to keep her word, but then Alexis, tired of waiting, might go to seek the blacksmiths daughter in the village and find the real Akulina—a stout, pockmarked girl—and so discover the hoax. Alarmed at this she determined to re-enact the part of Akulina. Alexis was enchanted. All day he thought about his new acquaintance and at night he dreamt of her. It was scarcely dawn when he was up and dressed. Without waiting even to load his gun he set out followed by the faithful Shogar, and ran to the meeting place. Half an hour passed in undeniable delay. At last he caught a glimpse of a blue sarafan among the bushes and rushed to meet dear Akulina. She smiled to see his eagerness; but he saw traces of anxiety and melancholy on her face. He asked her the cause, and she at last confessed. She had been flighty and was very sorry for it. She had meant not to keep her promise, and this meeting at any rate must be the last. She begged him not to seek to continue an acquaintance which could have no good end. All this, of course, was said in peasant dialect; but the thought and feeling struck Alexis as unusual in a peasant. In eloquent words he urged her to abandon this cruel resolution. She should have no reason for repentance; he would obey her in everything, if only she would not rob him of his one happiness and let him see her alone three times or even only twice a week. He spoke with passion, and at the moment he was really in love. Lisa listened to him in silence.

"Promise," she said, "to seek no other meetings with me but those which I myself appoint."

He was about to swear by the Holy Friday when she stopped him with a smile.

"I do not want you to swear.Your word is enough."

Then together they wandered talking in the wood, till Lisa said:

"It is time."

They parted; and Alexis was left to wonder how in two meetings a simple rustic had gained such influence over him.There was a freshness and novelty about it all that charmed him, and though the conditions she imposed were irksome, the thought of breaking his promise never even entered his mind.After all, in spite of his fatal ring and the mysterious correspondence, Alexis was a kind and affectionate youth, with a pure heart still capable of innocent enjoyment.Did I consult only my own wishes I should dwell at length on the meetings of these young people, their growing love, their mutual trust, and all they did and all they said. But my pleasure I know would not be shared by the majority of my readers; so for their sake I will omit them. I will only say that in a brief two months Alexis was already madly in love, and Lisa, though more reticent than he was, not indifferent. Happy in the present they took little thought for the future. Visions of indissoluble ties flitted not seldom through the minds of both. But neither mentioned them. For Alexis, however strong his attachment to Akulina, could not forget the social distance that was between them, while Lisa, knowing the enmity between their fathers, dared not count on their becoming reconciled. Besides, her vanity was stimulated by the vague romantic hope of at last seeing the lord of Tugilovo at the feet of the daughter of a village blacksmith. Suddenly something happened which came near to change the course of their true love. One of those cold bright mornings so common in our Russian autumns Ivan Berestoff came a-riding. For all emergencies he brought with him six pointers and a dozen beaters. That same morning Grigori Muromsky, tempted by the fine weather, saddled his English mare and came trotting through his agricultural estates. Nearing the wood he came upon his neighbour proudly seated in the saddle wearing his fur-lined overcoat. Ivan Berestoff was waiting for the hare which the beaters were driving with discordant noises out of the brushwood. If Muromsky could have foreseen this meeting he would have avoided it. But finding himself suddenly within pistol-shot there was no escape. Like a cultivated European gentleman, Muromsky rode up to and addressed his enemy politely. Berestoff answered with the grace of a chained bear dancing to the order of his keeper. At this moment out shot the hare and scudded across the field. Berestoff and his groom shouted to loose the dogs, and started after them full speed. Muromsky's mare took fright and bolted. Her rider, who often boasted of his horsemanship, gave her her head and chuckled inwardly over this opportunity of escaping a disagreeable companion. But the mare coming at a gallop to an unseen ditch swerved. Muromsky lost his seat, fell rather heavily on the frozen ground, and lay there cursing the animal, which, sobered by the loss of her master, stopped at once. Berestoff galloped to the rescue, asking if Muromsky was hurt. Meanwhile the groom led up the culprit by the bridle. Berestoff helped Muromsky into the saddle and then invited him to his house. Peeling himself under an obligation Muromsky could not refuse, and so Berestoff returned in glory, having killed the hare and bringing home with him his adversary wounded and almost a prisoner of war.

At breakfast the neighbours fell into rather friendly conversation; Muromsky asked Berestoff to lend him a droshky, confessing that his fall made it too painful for him to ride back.Berestoff accompanied him to the outer gate, and before the leavetaking was over Muromsky Pad obtained from him a promise to come and bring Alexis to a friendly dinner at Prelutchina next day.So this old enmity which seemed before so deeply rooted was on the point of ending because the little mare had taken fright.

Lisa ran to meet Per father on his return.

"What has happened, papa?"she asked in astonishment."Why are you limping?Where is the mare?Whose droshki is this?"

"My dear, you will never guess;"—and then he told Per.

Lisa could not believe Per ears.Before she Pad time to collect herself she heard that to-morrow both the Berestoffs would come to dinner.

"What do you say?"she exclaimed, turning pale."The Berestoffs, father and son!Dine with us to-morrow!No, papa, you can do as you please, I certainly do not appear."

"Why?Are you mad?Since when have you become so shy? Have you imbibed hereditary hatred like a heroine of romance? Come, don't be afoot."

"No, papa, nothing on earth shall induce me to meet the Berestoffs."

Her father shrugged his shoulders, and left off arguing.He knew he could not prevail with her by opposition, so he went to bed after his memorable ride.Lisa, too, went to her room, and summoned Nastia.Long did they discuss the coming visit.What will Alexis think on recognising in the cultivated young lady his Akulina?What opinion will he form as to her behaviour and her sense?On the other hand, Lisa was very curious to see how such an unexpected meeting would affect him.Then an idea struck her.She told it to Nastia, and with rejoicing they determined to carry it into effect.

Next morning at breakfast Muromsky asked his daughter whether she still meant to hide from the Berestoffs.

"Papa," she answered, "I will receive them if you wish it, on one condition.However I may appear before them, whatever I may do, you must promise me not to be angry, and you must show no surprise or disapproval."

"At your tricks again!"exclaimed Muromsky, laughing."Well, well, I consent; do as you please, my black-eyed mischief." With these words he kissed her forehead, and Lisa ran off to make her preparations.

Punctually at two, six horses, drawing the home-made carriage, drove into the courtyard, and skirted the circle of green turf that formed its centre.

Old Berestoff, helped by two of Muromsky's servants in livery, mounted the steps.His son followed immediately on horseback, and the two together entered the dining-room, where the table was already laid.

Muromsky gave his guests a cordial welcome, and proposing a tour of inspection of the garden and live stock before dinner, led them along his well-swept gravel paths.

Old Berestoff secretly deplored the time and trouble wasted on such a useless whim as this Anglo-mania, but politeness forbade him to express his feelings.

His son shared neither the disapproval of the careful farmer, nor the enthusiasm of the complacent Anglo-maniac.He impatiently awaited the appearance of his hosts daughter, of whom he had often heard; for, though his heart as we know was no longer free, a young and unknown beauty might still claim his interest.

When they had come back and were all seated in the drawing-room, the old men talked over bygone days, re-telling the stories of the mess-room, while Alexis considered what attitude he should assume towards Lisa. He decided upon a cold preoccupation as most suitable, and arranged accordingly.

The door opened, he turned his head round with indifference—with such proud indifference—that the heart of the most hardened coquette must have quivered. Unfortunately there came in not Lisa but elderly Miss Jackson, whitened, laced in, with downcast eyes and her little curtsey, and Alexis' magnificent military movement failed. Before he could reassemble his scattered forces the door opened again and this time entered Lisa. All rose, Muromsky began the introductions, but suddenly stopped and bit his lip. Lisa, his dark Lisa, was painted white up to her ears, and pencilled worse than Miss Jackson herself. She wore false fair ringlets, puffed out like a Louis XIV. wig; her sleeves à l'imbécille extended like the hoops of Madame de Pompadour. Her figure was laced in like a letter X, and all those of her mother's diamonds which had escaped the pawnbroker sparkled on her fingers, neck, and ears. Alexis could not discover in this ridiculous young lady his Akulina. His father kissed her hand, and he, much to his annoyance, had to do the same. As he touched her little white fingers they seemed to tremble. He noticed, too, a tiny foot intentionally displayed and shod in the most coquettish of shoes. This reconciled him a little to the rest of her attire. The white paint and black pencilling—to tell the truth—in his simplicity he did not notice at first, nor indeed afterwards.

Grigori Muromsky, remembering his promise, tried not to show surprise; for the rest, he was so much amused at his daughter's mischief, that he could scarcely keep his countenance.For the prim Englishwoman, however, it was no laughing matter.She guessed that the white and black paint had been abstracted from her drawer, and a red patch of indignation shone through the artificial whiteness of her face.Flaming glances shot from her eyes at the young rogue, who, reserving all explanation for the future, pretended not to notice them.They sat down to table, Alexis continuing his performance as an absent-minded pensive man.Lisa was all affectation.She minced her words, drawled, and would speak only in French.Her father glanced at her from time to time, unable to divine her object, but he thought it all a great joke.The Englishwoman fumed, but said nothing.Ivan Berestoff alone felt at his ease.He ate for two, drank his fill, and as the meal went on became more and more friendly, and laughed louder and louder.

At last they rose from the table.The guests departed and Muromsky gave vent to his mirth and curiosity.

"What made you play such tricks upon them?"he inquired."Do you know, Lisa, that white paint really becomes you?I do not wish to pry into the secrets of a lady's toilet, but if I were you I should always paint, not too much, of course, but a little."

Lisa was delighted with her success.She kissed her father, promised to consider his suggestion, and ran off to propitiate the enraged Miss Jackson, whom she could scarcely prevail upon to open the door and hear her excuses.

Lisa was ashamed, she said, to show herself before the visitors—such a blackamoor.She had not dared to ask; she knew dear kind Miss Jackson would forgive her.

Miss Jackson, persuaded that her pupil had not meant to ridicule her, became pacified, kissed Lisa, and in token of forgiveness presented her with a little pot of English white, which the latter, with expressions of deep gratitude, accepted.

Next morning, as the reader will have guessed, Lisa hastened to the meeting in the wood.

"You were yesterday at our master's, sir?"she began to Alexis."What did you think of our young lady?"

Alexis answered that he had not observed her.

"That is a pity."

"Why?"

"Because I wanted to ask you if what they say is true."

"What do they say?"

"That I resemble our young lady; do you think so?"

"What nonsense, she is a deformity beside you!"

"Oh! barin, it is a sin of you to say so. Our young lady is so fair, so elegant! How can I vie with her?"

Alexis vowed that she was prettier than all imaginable fair young ladies, and to appease her thoroughly, began describing her young lady so funnily that Lisa burst into a hearty laugh.

"Still," she said, with a sigh, "though she may be ridiculous, yet by her side I am an illiterate fool."

"Well, that is a thing to worry yourself about. If you like I will teach you to read at once."

"Are you in earnest, shall I really try?"

"If you like, my darling, we will begin at once."

They sat down.Alexis produced a pencil and note-book, and Akulina proved astonishingly quick in learning the alphabet.Alexis wondered at her intelligence.At their next meeting she wished to learn to write.The pencil at first would not obey her, but in a few minutes she could trace the letters pretty well.

"How wonderfully we get on, faster than by the Lancaster method."

Indeed, at the third lesson Akulina could read words of even three syllables, and the intelligent remarks with which she interrupted the lessons fairly astonished Alexis.As for writing she covered a whole page with aphorisms, taken from the story she had been reading.A week passed and they had begun a correspondence.Their post-office was the trunk of an old oak, and Nastia secretly played the part of postman.Thither Alexis would bring his letters, written in a large round hand, and there he found the letters of his beloved scrawled on coarse blue paper.Akulina's style was evidently improving, and her mind clearly was developing under cultivation.