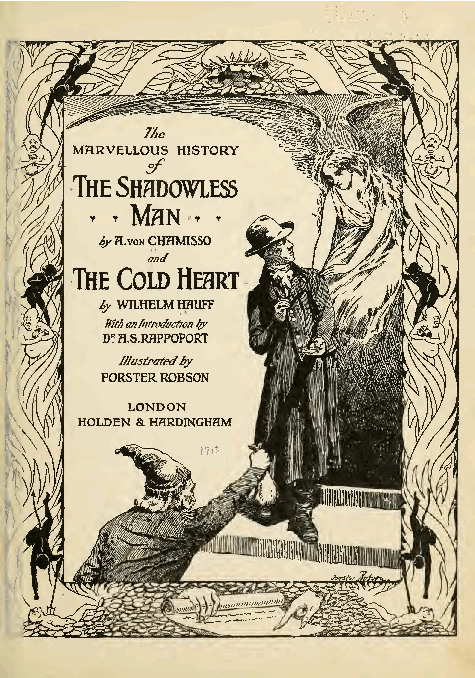

The Marvellous History of the Shadowless Man, and The Cold Heart

Summary

Play Sample

THE COLD HEART

INTRODUCTION

WILHELM HAUFF

Wilhelm Hauff was born on the 29th November, 1802, at Stuttgart, and died in the same town on the 18th November, 1827, within a few days of completing his twenty-fifth year.

Losing his father when but six years of age, he was placed in the care of his grandfather in Tübingen, and was later sent to a convent school at Blaubeuren.Returning to Tübingen, he devoted four years, 1820-24, to the study of theology, and was appointed tutor to the family of Baron von Hügel in Stuttgart.

It was at this time that Hauff began his remarkable literary career with the publication in November, 1825, of his "Fairy Tale Annual for 1826."The years 1826 and 1827 saw the appearance of two succeeding annuals of fairy stories, which were everywhere received with the most enthusiastic admiration.

Hauff's productivity was truly amazing; in four years he wrote, besides the fairy-tales, poems, short stories, fantasies satirical and humourous, and the classic novel "Lichtenstein," all of which have gained an enduring place in German literature.

Returning from a journey through France, Holland and North Germany, Hauff was appointed to the literary editorship of the "Morgenblatt," a position which enabled him to marry, the wedding taking place in Nördlingen, on the 13th February, 1827.

Hauff's journalistic duties did not interfere with his activity in other spheres of literary work.In this last year of his short life he continued to produce short stories and fantasies, his experiences while on his travels furnishing him with plenty of material.Indeed, it was while on a journey that he wrote the second "Fairy-tale Annual."

Shortly after his marriage he set himself to the composition of his third a final "Annual"--the connecting story of which is entitled "The Inn in Spessart," and in which occurs the story of "The Cold Heart," a new translation of which is published in the present volume.

Hauff's brilliant career was now drawing to a close.The last work to proceed from his pen was the playful fantasy, "Phantasien im Bremer Ratskeller."Early in November, 1827, a daughter was born to him; but he was already suffering from an attack of typhoid fever, to which he succumbed on the 18th day of the same month.

Notwithstanding the genius displayed in his other works, the "Fairytales" will always be regarded as the most precious legacy which the great author has bequeathed to posterity; and of these "The Cold Heart" holds undoubtedly the first place in popular esteem.Unlike the majority of his fairy-tales, it owes something of its origin to folk-lore, as it is based on an old Black Forest Legend.But the human figures in the story are Hauff's very own; those conversant with the master's works will recognise in Charcoal Peter and Fat Ezekiel characters which only Hauff could have created.

As in all his fairy-tales the human element is supreme, even Dutch Michael and the Glassmanikin evince more human characteristics than supernatural, and though they came from a mythological source they never appear to us pale and colourless as the supernatural beings in the fairy-tales of the brothers Grimm.Having chosen the groundwork of his story, Hauff developed it with all the force of his vivid imagination, fantastic humour and rare talent for narration.

H.Robertson Murray

THE COLD HEART

PART I

He who travels through Suabia should not pass without seeing something of the Black Forest; not because of the trees, although such countless masses of stately pines are not to be met with everywhere; but because of the people, who differ remarkably from their neighbours on every side.They are broad-shouldered and strong-limbed and taller than the generality of human beings; it is as if the invigorating air, which blows every morning through the pines, has endowed them with a freer respiration, a clearer eye and a firmer though, perhaps, rougher courage than is possessed by the dwellers in valley and on plain.And not only in bearing and stature, but also in customs and dress they form a marked contrast to those who live beyond the confines of the forest.The costume of the Baden Black Forester is the more picturesque: with full-grown beards, as in accordance with Nature's intention, the men, in their black jerkins, their enormous narrow-pleated breeches, their red stockings and their peaked, broad-brimmed hats, have an air somewhat strange, but, at the same time, serious and dignified.These people are mostly occupied in glassblowing; but they are also noted for the manufacture of clocks, which are exported to all parts of the world.

On the other side of the forest dwell people of the same stock; but their employment has imparted to them habits, manners and customs differing from those of the glass-blowers.They are occupied with their forest, felling and splitting up the pine trees, which they float down the Nagold to the Necker, and thence to the Rhine and to far-away Holland.The Black Foresters and their rafts are familiar objects even to the inhabitants of the remote coast regions.The raftsmen touch at every town along the river, proudly awaiting offers for their baulks and beams; but the strongest and the longest of the former they sell for gold to the Mynheers, who build ships of them.These men are accustomed, therefore, to a rough, wandering existence.Their delight is to float down stream on their rafts, while the return homeward along the river-banks is but weary work.

Their holiday costume is also very different from that of the glass-blowers on the other side of the Black Forest.They wear dark linen jerkins with wide, green braces across their broad chests, and black leathern breeches, from the pocket of which peeps, as a badge of honour, the end of a brass foot-rule.But they take most joy and pride in their boots, the biggest, perhaps, which have ever been in fashion in any part of the world, for these are drawn quite two handspans above the knee, so that the raftsmen can wade knee deep in the water without getting wet.

Until quite recently the inhabitants of this forest believed it inhabited by supernatural beings, and it is only latterly that they have begun to abandon the superstition, and it is remarkable that even the forest spirits, which according to legend haunt the Black Forest, are also distinguished by their different costume and habits.Thus we are assured, the Glass-manikin, a benevolent elf, of about four feet in height, is never seen in anything but a little peaked broad trimmed hat, with jerkin, knee-breeches and red stockings.

Dutch Michael again, who dwells on the other side of the forest, is said to be a gigantic, broad shouldered fellow, dressed in like fashion to the raftsmen; and many people, who have seen him, are wont to declare that they would not like to bear the cost of the calves, the skins of which have gone to the making of the boots."So big are they that an ordinary man could stand up to his neck in them," say the latter, protesting that the description is no exaggerated one.

Now, there is a story of the very strange adventure which a young Black Forester once had with these forest spirits, and which story I will now relate.

In the Black Forest there lived a widow, one Mistress Barbara Munk; her husband had been a charcoal burner, and after his death she brought up her son, a lad of sixteen, to the same calling.Peter Munk, a slenderly built young fellow, took to the business as a matter of course, because he had never seen his father do aught else but sit by his smoking charcoal-kiln, or, blackened and begrimed, travel to the towns to sell his charcoal.

Now, a charcoal-burner has a great deal of time for meditation on things as they are, and on himself; and as Peter Munk sat before his kiln, the dark trees around him and the heavy silence of the forest stirred his heart to sorrow and to vague longings.He felt grieved and vexed at something; but what that something was he could not tell.At last, the cause of his discontent was revealed to him: it was--his position in the world.

"A grimy, lonely charcoal-burner!"he exclaimed to himself."What a wretched existence!Look at the glassblowers, the watchmakers, even the musicians who play on Sunday evenings--how they are respected!And I, Peter Munk, though cleaned up and dressed in my father's best jerkin with the silver buttons, and with my brand-new red stockings on, if someone follows me and asks himself 'Who can that slim young fellow be?'--admiring my stockings and easy gait, no sooner does he pass me and chance to look round, than he exclaims, 'Pooh, it's only that charcoal-burning Peter Munk after all.'"

The raftsmen on the other side of the forest were also objects of his envy.When these giants came over to his side of the forest, in all their glory of apparel, their buttons, chains and buckles representing great weight and wealth of silver; when they stood with outstretched legs looking on at the dancing, swearing Dutch oaths, and smoking yard-long Rhenish pipes like the grandest Mynheers, each of these handsome raftsmen appeared to him to be a perfect representation of a really happy man.And when one of these lucky fellows chanced to dive his hands into his pockets, bringing forth whole handsful of silver thalers, and throwing them down on the dice table, five gulden here, ten there, Peter became well-nigh distracted, and slunk dolefully back to his hut; for on many a festival he had seen one or other of these woodsmen play away more money than his poor father had been able to earn in a year.

There were three of these men in particular of whom he could not say which he admired the most.One was a big, fat, red-faced man, generally conceded to be the richest person in those parts.He was called Fat Ezekiel.Twice a year he travelled to Amsterdam with building timber, and always had the good fortune to dispose of it at so much better profit than his comrades could, that he was able to travel homewards in luxurious style, while they were compelled to return on foot.

The second was the tallest and lankiest fellow in the whole forest.He was called Lanky Schlurker, and Munk envied him because of his extraordinary boldness.He would flatly contradict the most worthy people, and always took up more room in the overcrowded tavern than was required by four others of the bulkiest, leaning with both elbows on the table, or stretching his legs along the bench; yet nobody dared to complain, for he was fabulously rich.

The third was a handsome young man, the best dancer for miles round, who had earned the nickname of the Dance King.He had formerly been a poor man in the service of a wealthy timber merchant; but all at once he had become immensely rich.Some said that he had found a jar, full of money, at the root of an old pine tree; others maintained that not far from Bingen on the Rhine he had brought up with his pole, such as the raftsmen use to spear fish, a bundle filled with gold, and that this bundle had formed part of the great Nibelung's hoard which lies buried there.But no matter--the fact was that he had suddenly become rich, and was consequently respected by young and old as if he had been a prince.

The charcoal-burner, Peter Munk, thought long and oft of these men as he sat alone among the pine-trees.All three of them had one great failing which made them hated by all; and this common failing was their inhuman avarice, their callousness towards debtors and the poor, for the Black-foresters were a kindly and good-hearted people.Nevertheless, as is often found in such cases, though they were hated because of their covetousness, they were held in awe because of their money; for who but they could fling thalers broadcast as though by simply shaking the pine-trees the money fell into their hands.

"I cannot endure this any longer!"said Peter to himself, sorely depressed, one day when there had been a fête, and the people had foregathered in the tavern to enjoy themselves."If I do not soon have a stroke of luck, I shall be doing myself some harm.Oh, if I were only as rich and feared as Fat Ezekiel, or as bold and strong as the Lanky Schlurker, or as famous as the Dance King, throwing thalers instead of kreuzers to the musicians, as he does!Where the fellow gets his money from is a mystery to me!"He turned over in his mind all possible means of earning money, but none attracted him; at last, he fell to reflecting on the stories which he had heard of people who in bygone times had become rich through the aid of Dutch Michael or the Glassmanikin.While his father was alive, other poor folk would often pay him visits, and the conversation would turn on rich people and how they had gained their wealth.In these stories the Glassmanikin often played a part.Indeed, after some striving, Peter was able to recall a portion of the little rhymed incantation which had to be pronounced in the depths of the forest before the Glassmanikin would appear.It began thus:

"Guardian of gold in the pine-tree wold,

Art many hundred ages old.

Lord of all lands where pine-trees grow."

But tax his memory as he might, he could not recollect any more of the rhyme.He often felt inclined to question this or that old man how the little incantation ran, but a certain shyness always prevented him from betraying the drift of his thoughts.He came also to the conclusion that not many could be acquainted with the story of the Glassmanikin, and but few could know the incantation, as there were hardly any rich people in the forest, and--but why had not his father and other poor folk tried their luck?At last, he coaxed his mother to talk of the Glassmanikin; but she could only tell him what he already knew, being able to quote only the first line of the rhymed incantation, although she informed him, at length, that the goblin showed himself only to those born on a Sunday between the hours of eleven and two.He himself, having been born at noon on a Sunday, was, therefore, one of the elect, if he but knew the incantation.

When Charcoal-Peter Munk heard this he could scarcely contain himself with joy and eagerness to make the adventure.Because he knew a part of the incantation and was born on Sunday, he conjectured that the Glassmanikin would surely show himself.One day, therefore, having sold all his charcoal he kindled no fresh fires in his kilns, but dressed himself in his father's state-jerkin and new red stockings, donned his Sunday hat, took his five-foot blackthorn stick in hand, and bade farewell to his mother."I must go to the mayoralty in town," he said, "for we have to draw lots as to who shall serve as soldier, and I will impress it on the mayor, for once and for all, that you are a widow and that I am your only son."

His mother having commended his resolution, he made his way to the Pine-grove.The Pine-grove lies on the highest point of the Black Forest, for miles around which there lay at that time no village, not even a hut, for the superstitious people believed that the spot was haunted.Further, no one cared to fell wood in that quarter, though the pines there grew tall and stately, for it often happened that when woodcutters were at work there, their axeheads flew from the hafts and wounded them in the foot, or the trees fell over without warning, injuring and even killing the men round about; besides which, even the finest trees growing there were only used as firewood, for the raftsmen never took any timber from the Pine-grove, because the saying went that man and wood would surely come to grief if a tree from the Pine-grove found itself in a raft.This is the reason why the trees grew so thick and tall in the Pine-grove, so that even in the brightest sunshine all was as dark as night.Well might Peter Munk shudder with fear, for he could hear no sound of of human voice, no ring of axe, and no footfall save his own; even the very birds appeared to shun this awesome grove.

Having reached the highest point in the Pine-grove, Charcoal-Peter Munk stood before a pine of huge circumference, one for which any Dutch ship-builder would have given many hundred guilders on the spot.

"This must be the place," thought Peter, "where the Treasure-guardian lives."Saying which, he doffed his big Sunday hat, made a deep bow before the tree, cleared his throat and spoke in a trembling voice: "I wish you a very good evening, Master Glassmanikin!"

No answer--all was as silent as before.

"Perhaps I had better recite the little verse," thought Peter, and straightway began to mutter:

"Guardian of gold in the pine-tree wold,

Art many hundred ages old;

Lord of all lands where pine-trees grow."

As he uttered these words he saw to his amazement a tiny, weird figure peeping forth from behind the great pine tree.He fancied he could see the little Glassmanikin just as the latter had been described to him, with his little black jerkin, little red stockings, little hat; everything, indeed, even the pale, but wise and refined little face of which he had heard so much.But, alas!the Glassmanikin vanished as quickly as he had appeared.

"Master Glassmanikin!"said Peter Munk, after a moment's hesitation, "please don't take me for a fool!--Master Glassmanikin, if you think that I did not catch sight of you, you are greatly mistaken: I saw you quite clearly peeping from behind the tree."

Still no answer, though, at times, he fancied he could hear a faint, hoarse chuckle from behind the tree.Finally, his impatience overcame his fear, which until now had restrained him.

"Just you wait a moment, you little beggar," he cried out, "I'll soon have you!"and at one bound he was behind the pine-tree, but there was no "guardian of gold in the pine-tree wold," nothing but a pretty little squirrel clambering away up the tree.

Peter Munk shook his head; he perceived that he had succeeded in working the spell to a certain degree; and if he could only think of the last line to the rhyme he would be able to induce the Glassmanikin to show himself.He pondered, and pondered, and pondered, but all to no purpose.He could see the little squirrel perched on the lowest branch of the pine, and he could not be sure whether it was trying to inspire him with courage or only making fun of him.It cleaned itself, whisked its beautiful tail to and fro, gazing at him all the while with intelligent eyes, until he began to be almost afraid of being alone with the creature; for, at one moment, the little squirrel appeared to have a human head covered with a three cornered hat; then it looked just like any other squirrel, except that on its hind legs it had red stockings and black shoes.In short it was a comical creature; but, nevertheless, it made Charcoal Peter feel quite uncomfortable, for it seemed to him to be so uncanny.

Peter returned at a quicker pace than he had gone thither.The gloom of the pine-forest seemed to be intensified, the trees grew in denser clumps, and at last he was so fearful that he broke into a run, and did not regain courage until he heard dogs barking in the distance, and saw, shortly afterwards the smoke from a cottage rising between the trees.On drawing nearer, he was able to distinguish the costume of the people in the cottage, and he realised to his consternation that he had fled in exactly the opposite direction to the one he had intended, and had arrived among the raftsmen instead of among the glass-blowers.The cottagers were wood-fellers, and the family consisted of an old man, his son, who was the owner of the cottage, and some grown-up grandchildren.They bade Charcoal-Peter a kindly welcome when he asked for a night's lodging, without questioning him as to his name or whence he came, offered him cider to drink, and set on the table for supper a large woodcock, which is the choicest dish of the Black Forest.

Dutch Michael felling the trees.

After supper the housewife and her daughters betook themselves to their spinning, sitting round the large burning wood-splinter, which served as light and which the young people kept fed with the finest pine-resin, while the grandfather, the house-owner and their guest smoked and watched the women, and the boys busied themselves cutting spoons and forks out of wood.Without, in the forest the storm howled and rushed through the pines, heavy thuds being heard every now and then, as if whole trees were being torn up by the roots and flung to earth.The fearless youngsters wanted to run out into the forest to witness the scene in all its awful grandeur, but their grandfather forbade them with stern words and looks."I advise no one to set foot outside the door this night," he cried to them; "he who does so will never return; for Dutch Michael is abroad to-night hewing down timber for a new raft."

The young ones stared at him; although they must have heard many a time of Dutch Michael, yet they begged their grandfather to relate them once more some good story of that forest-spirit.Peter Munk, also, who had only heard vague rumours of Dutch Michael on his side of the forest, chimed in with the others and begged the old man to say who and what he might be.

"He is the lord of this forest," answered the old man, "and for one of your age not to have heard of him tells me that your home lies on the other side of the Pine-grove, or even farther off.But I will relate to you what I know of Dutch Michael, and what people say of him.About a hundred years ago, at least, so my grandfather told me, there were no more honourable people than the Black-Foresters in the whole world.But now that money is so plentiful, dishonesty and evil are everywhere.Our young lads dance and riot on the Sabbath, and swear terribly.But formerly it was quite otherwise, and, though he himself were to look through the window at this moment, I say, as I have said time and again, that Dutch Michael is to blame for all the mischief.Well--one hundred or more years ago, there lived a rich timber merchant who had a very large business; he traded far away down the Rhine, and his affairs prospered, for he was a good Christian.One evening there came to his door a man, the like of whom he had never cast eyes upon.He was dressed as one of our young Black-Foresters, but was a good head taller than any of them; indeed, one could hardly have believed that there was such a giant in existence.The fellow asked the merchant for work, and the latter, seeing how strong and capable of doing heavy work he looked, was ready to engage him at a fair wage.So the matter was agreed upon.Michael turned out to be a workman such as that merchant had never yet employed.He was equal to three men at felling trees, and where it took six men to carry one end of a trunk, he could manage the other end all by himself.But after six months at tree-felling, he went one day to his master, and demanded of him: 'I have been hewing wood long enough in this place, and I would like to know where the felled trunks go; how would it be if you were to let me go for a time on one of your rafts?'"

The timber merchant replied: "I won't stand in your way, Michael, if you want to see a bit of the world.It's true that I am in sore need of strong fellows like yourself for the tree-felling, while on the rafts it is more a question of skill.For this once, however, you may go!"

And thus it was; the raft upon which he was to go was in eight parts, the last part being composed of enormous roof-beams. But what happened?The night before starting, this huge fellow brought down to the water yet another eight beams, bigger and longer than any that had ever been seen, so much so that everybody was amazed.And no one knows to this day where he had felled them.The merchant chuckled to himself when he calculated the price these beams would fetch.But Michael said: "These are for me to travel upon, for I could not make any headway on those little splinters."

His grateful master then wished to present him with a pair of raftsmen's boots, but Michael put them aside, and brought forth another pair, such as had never before been made.My grandfather used to declare that they must have weighed a hundred pounds, and were five feet in length.

The raft went on its way, and as Michael had hitherto astonished the wood-cutters, he now caused the raftsmen to marvel; for the raft, instead of going more slowly down the stream, as one would have thought, taking the monstrous baulks into consideration, it simply flew forward like an arrow as soon as it reached the Neckar.And when it came to a bend in the river where otherwise the raftsmen would have had trouble to keep the raft in mid-stream or to prevent it from stranding, Michael would spring into the water, and with one push would force the raft to left or right, so that it escaped danger; and if they came to a shallow, he ran to the forepart of the raft, made them all lay aside their poles, laid a huge round beam on the sandbank, and with one push the raft sped over, so fast that land, trees and villages seemed to fly past.Thus they came to Cologne in about half the time it usually takes.Here it was that the wood was always sold at that time; but Michael addressed the raftsmen: "I can see that you are all good business men, and know how to manage your affairs to the best advantage!Do you suppose that here in Cologne they want all the timber which comes from the Black Forest for their own use?Not at all: they buy it from you at half its value, and then sell it at a higher price in Holland.Let us sell our smaller beams here, and then go on to Holland with the big ones; and what we receive above the usual price will be for our own profit."

Thus spoke the cunning Michael, and the others agreed; some because they wished to go to Holland, others for the sake of the money.There was only one honest man among them, and he tried to dissuade them from risking their master's goods, and from cheating him out of any higher price they might get.But they would not listen to him, and soon forgot the words he had said; though Dutch Michael did not forget them.

The raft continued its journey down the Rhine with Michael in command, so that it soon arrived at Rotterdam.There they received about four times the price usually obtained, while Michael's huge baulks fetched an enormous sum of money.When the Black Foresters saw so much gold they could scarcely contain themselves for joy.Michael divided the money into four parts, setting aside one for the master, and dividing the remainder among the men.With this they mixed with sailors and evil characters, spending their money in dissipation and debauchery in the taverns.As to the honest man, who had warned them, Dutch Michael is said to have sold him to a slave-dealer, for nothing more was ever heard of him.

From that day forth Holland has been the paradise of our Black Forest lads; the timber merchants knew nothing of this trade, and all the while money, swearing, evil habits, drink and gambling were being introduced by the raftsmen from Holland.

Dutch Michael, so the story goes, disappeared and was nowhere to be found; but it is certain that he did not die.For one hundred years his spirit has haunted the forest, and it is said that he has helped many to become rich, at the cost of their poor souls, of which I would rather not say any more.This much is certain, that on such stormy nights as this he is up in the Pine-grove, where no one fells trees, selecting the biggest pines.And my father has seen him take hold of one, four to five feet in thickness, and snap it as one would a reed.This is his gift to those who turn from the straight path to go to him; at midnight they carry their timber to the water, and fare away on it into Holland.Oh, if I were only king and lord of Holland, I would send him to the bottom with grape-shot; for every ship, the hull of which contains one single beam of Dutch Michael's felling, must come to grief.And that is the reason why one hears of so many shipwrecks; how otherwise could a fine, strong ship, as big as a church, sink in the open sea?Every time Dutch Michael fells a pine on a stormy night in the Black Forest, one of his old ones is sprung from the bottom of some ship, the water rushes in, and that ship with all on board is lost.

Such is the story of Dutch Michael, and it is but the truth when people declare that he is the author of all the evil which is committed in the Black Forest!

"Ah!he can make you rich enough!"continued the old man, confidentially."But I would receive nothing at his hands, not for all the gold in the world would I stand in the shoes of Fat Ezekiel or the Lanky Schlurker.And it is also thought that the Dance-King is one of his familiars."

The storm had abated during the recital of the old man's story; the girls lit the lamps, and stole away; the men gave Peter Munk a sack full of leaves to serve as a pillow, and left him to sleep on the hearth, wishing him good-night as they went.

Never in his life had Charcoal-Peter dreamed so heavily as during that night.First there appeared to him the dark gigantic form of Dutch Michael, who wrenched open the window and stretched an enormously long arm into the room, in the hand of which was a purse full of gold pieces, which he shook so that the money jingled temptingly.Then he saw the little, friendly Glassmanikin riding round the room on a huge green bottle, and he seemed again to hear that hoarse chuckle he had heard in the Pine-grove.Then it was as if someone was murmuring in his left ear:

"From Holland comes Gold!

Canst have it, if bold.

For payment soon told!

Gold! Gold!"

Then again in his right ear he heard the little rhyme beginning:

"Guardian of gold in the pine tree wold!"

and a soft voice whispered: "Stupid Charcoal-Peter!silly Peter Munk!cannot you find a rhyme to 'grow,' and yet you were born at noon on a Sunday!Rhyme, stupid Peter, rhyme!"

Peter's dream in thee woodman's cottage.

He sighed and groaned in his sleep, he tried hard to find a rhyme; but as he had never been able to make one when awake, to do so in a dream was equally beyond him.But when he awoke with the first flush of dawn, his dream seemed to have been very wonderful; he sat with folded arms at the table, and thought of the whispered exhortation which still resounded in his ear: "Rhyme, stupid Charcoal-Peter, rhyme!"he repeated to himself, pressing his finger to his forehead; but no rhyme was forthcoming.But while he sat there, staring despondently in front of him and trying to think of a rhyme to "grow," three lads passed the house on their way through the forest, and one of them was singing as he trudged along:

"To the mountains there above,

To the heights where pine-trees grow,

I go to meet my love;

She's true to me, I know."

The words thrilled Peter's senses like a flash of lightning.He leapt to his feet and rushed out of the house, for he was not sure whether he had caught the words correctly.He ran after the three lads, and seized the singer by the arm.

"Stop, my friend!"he cried, "what was it you made to rhyme with 'grow'?For the love of Heaven tell me what you were singing?"

"What ever is the matter with you?"demanded the Black Forester."I can sing what I like--and if you don't leave go of my arm, I'll----"

"Not till you tell me what you were singing," screamed Peter, nearly beside himself, and gripping the other more tightly by the arm.

Seeing which, the two friends of the singer lost all patience, and started punching the wretched Peter with all their might until the pain he suffered forced him to loose his hold and to sink to his knees.

"Have you had enough?"they asked him, while laughing at him."Take care, you foolish fellow, that in future you do not molest people on the public highway."

"Ah, I will be careful enough as to that," replied Charcoal-Peter, dismally."But now that you have beaten me, be so good as to repeat slowly and distinctly what that friend of yours was singing."

At which all three once more burst out laughing, making game of him; but the singer repeated the words of his song for him, and, laughing and singing, they went their way.

"Then know is the word," said Peter Munk, getting once more on to his legs. "Know rhymes with grow--and now Master Glassmanikin we will have another little chat together."

"Have you had enough?"they asked him.

He returned to the cottage, took his hat and long stick, bade farewell to the cottagers, and strode away in the direction of the pine-grove.Becoming engrossed in thought, he slackened his speed, for it had occurred to him that, now he had found a rhyme, he must complete the verse.At length, approaching the Pine-grove, and reaching the part where the trees grow taller and denser, he completed the missing line, and his delight caused him to bound into the air.At the same moment there stepped from behind a pine a gigantic man, dressed as a raftsman, and with a pole as big as a ship's mast in his hand.Peter Munk sank in terror to his knees, as he saw the stranger striding slowly towards him.He felt that this could be none other than Dutch Michael.No sound came from the terrible apparition, while Peter stole fearful glances at him every now and then.He towered a full head above the tallest man whom Peter had ever seen; his features were not youthful in appearance, neither did he look old, though his face was a mass of wrinkles and furrows.He wore a linen jerkin, and his huge boots, which were drawn up well over his leather knee-breeches, were exactly as they had been described to Peter.

"Peter Munk!what are you doing in the Pine-grove?"asked the lord of the forest, at last, in deep, threatening tones.

"Good morning, countryman," answered Peter, trying to conceal his terror, but trembling violently all the same."I am going home through the Pine-grove."

"Peter Munk," rejoined the other, surveying him with a terrible penetrating look."Your way lies not through this glade."

"You are quite right," said Peter, "but it is so hot to-day, and I thought it would be cooler here."

"Utter no falsehoods, Charcoal-Peter!"thundered Dutch Michael; "or I will strike you to earth with my staff!Do you think that I have not seen you begging of that pigmy yonder?"And he continued in more gentle tones: "Go to!Go to!that was a silly thing to do, and well it was for you that you did not know the incantation.He is a niggard, that little fellow, and gives but little; and those to whom he gives have not enough wherewith to enjoy themselves.Peter, you are a poor simpleton, and my heart grieves for you; such a brave and handsome fellow as you are, one who should make his mark in the world, and yet but a charcoal-burner!While others can throw away whole armsful of thalers and ducats, you have but a few farthings to spend;--'tis a wretched existence."

"True!true!You are right!'Tis a miserable life!"

"Well, it is no fault of mine," pursued the terrible Michael; "I have already rescued many a brave fellow from misery, and you would not be the first.Tell me: how many hundred thalers do you want to begin with?"

As he spoke Michael rattled the money in his huge pocket, and the sound of it was as in the dream overnight.But his words caused Peter's heart to quake fearfully and painfully in his breast, he went hot and cold, for he did not look as one who offers gold out of compassion without expecting something in exchange.

Peter Munk, what are you doing in the pine grove?

There flashed into his mind the mysterious words of the old man when speaking of those who had become rich, whereupon, seized with indefinable horror and dread, he exclaimed: "Many thanks, good sir!but I would rather have nothing to do with you; I have heard enough of you already!"Saying which, he turned and ran away as fast as he could.

But the Forest demon, taking enormous strides, kept at his side, muttering in a dull and threatening voice: "You will repent this, Peter--so stands it written on your brow; I can read it in your eyes! You cannot escape me!--Run not so fast: hearken to a word of reason; yonder is the boundary of my domain."

Hearing this and seeing not far ahead a little ditch, Peter redoubled his speed in order to cross it and escape, and Michael was compelled to hurry in order to keep up with him, cursing and muttering threats the while.On coming to the ditch, the lad made a desperate leap, for he perceived that the demon had raised his staff to crush him with it.Luckily he managed to jump the ditch, and as he did so the staff flew into splinters as though it had struck against an invisible wall, while a large piece of it fell at Peter's feet.

He seized it, turning triumphantly to hurl it at the brutal Dutch Michael; but, in the same moment, he felt the wood moving in his hand, and discovered to his horror that he had hold of a huge snake, which was rearing its head at him with venomous tongue and glittering eyes.He loosened his grasp of it; but it had already entwined itself about his arm, bringing its swaying head nearer and nearer to his face.Then, in a flash, a monstrous woodcock swept down from above, seized the snake in its beak, and bore it aloft in the air.Dutch Michael, who had been watching the scene from the further side of the ditch, howled and shouted and raved as he saw the snake overpowered by this powerful antagonist.

"Then, in a flash, a monstrous woodcock swept down from

above and seized the snake in its beak."

Exhausted and trembling, Peter pursued his way; the path grew steeper, the scene ever wilder, until he found his way blocked by a huge pine-tree.

Bowing low towards the invisible Glassmanikin, just as he had done the day before, he began:

"Guardian of all in the pine-tree wold,

Art many hundred ages old,

Lord of all lands where pine-trees grow,

Thee only Sunday's children know."

"You haven't quite hit it, Charcoal-Peter; but as it is yourself, we will let it pass," said a soft clear voice close by him.He turned round in amazement; and there, under a splendid pine-tree, he saw a little, old manikin, clad in black jerkin and red stockings, and with a large hat on his head.He had a delicate friendly little face and beard, the latter as fine as a spider's web.And what was the more wonderful, he was smoking a pipe of blue glass; and Peter, on going nearer was astounded to see that the little man's clothes, shoes and hat were also made of coloured glass; yet it was as pliant as if still molten, for it folded and creased like cloth with every movement of the little body.

"So you have just met that vagabond, Dutch Michael," said the manikin, with an odd wheeze between each word."He tried to give you a good fright; but I have relieved him of that magic cudgel of his--it will never serve him again as a weapon."

"Yes, Master Guardian," replied Peter, with a deep bow "I was quite terrified.You must indeed have been that Master Woodcock which bit the snake to death; for which I thank you with all my heart.But I have come to you for advice; things are very bad and irksome with me; a charcoal-burner cannot do much for himself; and as I am still young, I thought that, perhaps, I could become something better.And I cannot help thinking of others, and how well they have done for themselves in a very short time--take, for example, that fellow, Ezekiel, and the Dance-King, why, money is to them as leaves in autumn."

"Peter," said the little man gravely, emitting a long puff of smoke from his mouth: "Peter, don't mention such people to me.What profit have those who are able to appear to be happy for a year or two, only at the cost of misery hereafter?You must not despise your trade; it was your father's and your grandfather's before you, and they were worthy men, Peter Munk!I should not like to think that it is love of idleness that has led you to me!"

The seriousness with which the manikin spoke disconcerted Peter."No, no," he replied, blushing."Idleness, I know well, Master Guardian, is the root of all evil; but you cannot blame me for preferring other trades to my own.Charcoal-burning is held by the world to be such a mean calling, while glassblowers, and raftsmen, and watchmakers and such like are highly respected."

"Pride often comes before a fall," replied the diminutive lord of the Pine-forest, in somewhat friendlier tones."You are a peculiar race, you human beings!It is seldom indeed that one is found who is contented with the lot to which he was born and bred.And to little purpose would it be if you did become a glass-blower, you would then yearn to be a timber-merchant; and were you timber-merchant, you would at once be coveting the post of forester or magistrate!Yet, so be it, Peter!if you promise me to be diligent, I will help you to something better.To every Sunday's child who knows how to find me, I am bound to accord three wishes.The first two I freely grant; but the third I can refuse, if it be a foolish one.Wherefore, Peter, wish yourself something: but take care that it is something good and useful!"

You hav'nt quite hit, Charcoal Peter.

"Hurrah!what a splendid Glass-manikin you are; you rightly deserve to be called Guardian, for you can dispense treasures indeed!Well--and so I may wish for whatever my heart desires!Now, for my first, I wish I could dance even better than the Dance-King, and could always have as much money in my pocket as Fat Ezekiel."

"You idiot!"cried the dwarf, angrily."What a miserable wish--to be a good dancer, and to have money wherewith to gamble!Are you not ashamed of yourself, you stupid Peter, to cheat yourself of so good a chance of happiness?What good will your dancing be to your mother or to yourself?How will your money help you, which, according to your wish, is only for the tavern, and will only stay there like that of the wretched Dance-King?For the rest of the week you will have nothing, and be no better off than before.One more wish I am to grant you; but take care you ask for something more sensible."Peter scratched his head, and after a little hesitation, said: "Well, I will wish myself the finest and richest glass-factory in the whole Black Forest with everything complete and money to carry it on."

"Nothing else?"asked the little man, anxiously."Nothing else, Peter?"

"Well--you might add a horse, and a little trap--"

"Oh, you stupid Charcoal-Peter!" exclaimed the dwarf, throwing his glass-pipe angrily against a big pine, where it shattered to atoms. "Horses! Traps! Sense, I say to you, good sense, sound common-sense and insight you should have wished for--not horses and traps. Ah well, don't be so downcast; we will see whether we cannot keep you from coming to harm, for the second wish was not so foolish on the whole. A good glass-factory will support both master and man; if you had only insight and understanding into the bargain, carriages and horses would have come of themselves."

"But, Master Guardian," remarked Peter, "I have still one wish left.I could wish for sense with that, if it is so supremely necessary as you say."

"No, no, Peter.You will find yourself in many an awkward fix yet, when you will be glad that you have still another wish left you.For the present, take yourself homewards.Here are two thousand guilders," continued the little forest gnome, drawing a little purse from his pocket."Be satisfied with them; for if you come here again asking for money, I shall have to hang you to the tallest of yonder pine-trees.Such has been my custom ever since I came to live in this forest.Old Winkfritz, who owned that large glass-factory in the lower part of the forest, died three days ago.Go thither early to-morrow morning, and make a bid for the property.Behave yourself, be industrious, and I will visit you from time to time, to be at hand with advice and help, seeing that you did not wish for common-sense.But--and I am now speaking in all seriousness--your first wish was a bad one.Have a care of becoming too fond of the tavern, Peter!it is a place which brings good to nobody in the long run!"

While speaking, the little man had pulled out another pipe of the finest flint-glass, and after filling it with dried pine-needles, had thrust it into his little, toothless mouth.He then produced a huge burning-glass, stepped into the sunlight and lit his pipe.This business over, he turned to Peter, and shook hands with him in the most friendly manner, gave him a few more words of advice, puffed away at his pipe even more vigorously until he disappeared in a cloud of smoke which gave forth an aroma of the finest Dutch tobacco as it curled slowly upwards among the pine branches overhead.

On arriving home, Peter found his mother in great trouble about him, for the good lady had come to the conclusion that her son must have enlisted as a soldier.But with great glee he bade her be of good cheer, telling her how he had fallen in with a good friend in the forest, who had advanced him money so that he could set himself up in a business other than charcoal-burning.Although his mother had been living for a good thirty years in the charcoal-burner's hut, and had grown as accustomed to the sight of grimy faces as a miller's wife to the flour-covered features of her husband, yet she was vain enough to despise her former station from the very moment in which Peter showed her the means to a more ostentatious way of life.

"Ah!"she said, "as the mother of the owner of a glass factory, my position is very different from that of my neighbours, Greta and Beta; in future I shall occupy a more prominent place in church, in a pew where the better class people sit."

Her son soon came to an agreement with the owners of the glass-factory.He kept on the old staff of workmen, and busied himself night and day in the manufacture of glass.At first, he was very interested in the work.It was his pleasure to go down to the glass-works, walking about with a pompous air and with his hands in both pockets, up and down, in and out, peeping in here, and peering in there, talking to this man, and then to that one, often causing his work-people to laugh heartily at his comments; while his chief delight was to watch the glass being blown, frequently taking a hand himself in the work, forming from the molten mass the most extraordinary patterns.

But too soon he began to weary of the business; at first, he was at the factory for only one hour per day, then only every other day, and, finally, only once a week, so that his workmen did just as they pleased.And it was all the result of his visits to the tavern.On the Sunday after his return from the Pine-grove, he went into the tavern, and who should be footing it on the dancing floor but the Dance-King; while Fat Ezekiel was already sitting behind a stoup of ale, throwing dice for crown-thalers.At sight of the latter Peter thrust his hands in his pockets to find out if the Glassmanikin had kept his word--and behold!his pockets were stuffed full of gold and silver pieces.Meanwhile, his legs were twitching and jerking as if they were itching to be dancing; so when the first dance was over, he took up a position with his partner exactly opposite the Dance-King.Whenever the latter sprang three feet into the air, Peter leapt four; and if his rival performed any particularly wonderful or graceful steps, Peter twirled and twisted his feet so that all beholders were well nigh beside themselves with delight and admiration.And when those at the dance heard that Peter had bought a glass-factory, and when they saw how he flung a small coin to the musicians every time he danced past them, there was no limit to their astonishment.Some were of opinion that he had discovered a treasure in the forest; others held that he must have inherited a fortune; while all paid him honour, and thought him to be a man of position, simply because he had money.He might gamble away twenty guilders in an evening, yet his pockets rattled and jingled just the same, as though they still contained hundreds of thalers.When Peter saw how much he was respected, he did not know how to contain himself, so great was his joy and pride.He threw money about by handsful, and was particularly liberal to the poor, because he himself knew what it was to feel the pinch of poverty.The supernatural ability of the new dancer soon cast all the feats of the Dance-King into the shade, and Peter was now hailed as "Dance-Emperor."The most venturesome gamblers did not stake so recklessly as he did, and therefore did not lose so heavily.But the more he lost, the more he gained--which was quite in accordance with the promise he had obtained from the Glassmanikin.He had wished always to have as much money in his pockets as there was in Fat Ezekiel's, and it was to him he lost most of his money.No matter whether he lost twenty or thirty guilders on a single throw, there they were again in his pocket as soon as Ezekiel had gathered them from the table.

Peter gambling at the Inn.

But gradually he brought his debauchery and gambling to a degree worse than that of the vilest character in the Black Forest; and he was more often dubbed Gambling-Peter than Dance-Emperor, for he was at the gambling table nearly the whole week through.Meanwhile his glass-business was going rapidly to rack and ruin, and it was all due to Peter's folly.He manufactured glass as fast as it could be made; but with the glass-factory he had not bought the secret how to manage it.In the end he had so much glass on hand that he did not know what to do with it; and he was forced to sell it at half its value to pedlars in order to find the money wherewith to pay his workpeople.One evening while returning home from the tavern, despite all the wine he had drunk to keep up his spirits, he could not help contemplating with terror and grief the ruin of his fortunes.All at once he noticed that somebody was walking at his side; he looked round, and behold--it was the Glassmanikin.He flew at once into a furious passion, bewailing his bad luck and cursing the little man as the cause of all his misfortune."What am I to do now with my horses and carts?"he said."Of what use to me is my factory and all my glass?Even when I was a miserable charcoal-burner, I was happier, and did not have all these worries.Now, I am expecting any day to see the bailiffs in my factory to sell me up in order to pay my debts."

"So-ho?"rejoined the Glassmanikin."So-ho?Then I am to be blamed for your misfortunes?Is this your gratitude for all my kindness to you?Did I not warn you not to make such foolish wishes.You wished to become a glass-blower, without having the slightest idea how to sell your glass.Did I not tell you not to wish too hastily?Common-sense, Peter, Wisdom, that was what you lacked."

"Bother your Common-sense and Wisdom!"cried the other."I am as clever a fellow as anyone else--and what is more I will prove it to you, Glassmanikin."Saying which he seized the little man by the collar, and shouted: "Ha!I have you now.Guardian of the pine-tree wold!And now I will make my third wish, which you will have to grant me.I demand, without delay, on this very spot, two hundred thousand thalers, and a house, and--oh-oh-ah!"he shrieked, wringing his hands, for the Glassmanikin had turned into a mass of white-hot glass, burning Peter's hand as if he had thrust it into fire; and in the same moment the manikin vanished.

For several days afterwards Peter's scorched and swollen hand reminded him of his ingratitude, and folly.But he soon turned a deaf ear to the voice of conscience, consoling himself with the reflection: "What if they do sell up my glass-factory and everything else.Fat Ezekiel is still left to me!So long as he has money on Sundays, I shall not go without."

Very good Peter!But supposing he should happen to have none at all, for once?

And this is what actually came to pass.One Sunday, Peter drove to the tavern, people observing him through their windows as he passed.

"There goes Gambling-Peter!"cried some; while others exclaimed: "Hullo, there's the Dance-Emperor, the rich Glass-manufacturer."But a few shook their heads, saying: "Don't be so sure about his wealth; why, everybody is talking about his debts, and it is rumoured among the townspeople that the bailiffs will soon be selling him up."

Meanwhile Peter bowed proudly and gravely to those he knew, and on arriving at the tavern, alighted from his carriage, crying out: "Good evening, landlord; has Fat Ezekiel yet arrived?"To which a deep voice replied: "Just come in, Peter?Your place has been kept for you, and we have got the cards out already."

Peter entered and got ready to play, well aware that Ezekiel must be well supplied with funds, for his own pockets were stuffed full with money.

Having taken his seat opposite the others he began playing, now winning, and now losing; and they kept on until such a late hour that all respectable people went off home.The lamps were lighted, and still they played on, until two of the players said: "There, that's enough!we must be getting home to wife and child."

But Gambling-Peter urged Fat Ezekiel to stay on.The latter was for a time unwilling, but said at last: "Well, I will just count my money, and then we will play at dice--and let the stake be five guilders, for to throw for less is child's play."

He pulled out his purse and counted his money, of which he found he had nearly a hundred guilders; whereby, Peter knew at once how much he himself had in his pockets without being under the necessity of reckoning.

But Ezekiel's luck had gone; exactly as he had been winning, hitherto, he now lost steadily at every throw, cursing heartily the while.If he threw a pair, Gambling-Peter followed with one, two pips higher.At length he laid his last five guilders on the table, saying: "One more throw, and if I lose, you can lend me some of your winnings, Peter, so that we can continue, for every good sportsman ought to help another."

"As much as you like, even to a hundred guilders," said the Dance-Emperor, rejoicing in his luck; whereupon Fat Ezekiel shook the dice-box and threw "fifteen."

"Good," he cried, "now we shall see."Peter threw eighteen, and as he looked he heard a harsh voice, not unknown to him, mutter in his ear: "So, here we are at the end of it all!"He swung round.There, standing directly behind him, towered the gigantic form of Dutch Michael.Stricken with surprise and horror he let the money, which he had just picked up from the table, slip through his fingers.

Fat Ezekiel apparently, had not noticed the demon, for he requested Gambling-Peter to lend him ten guilders so that he could go on playing.As one in a dream, Peter put his hand in his pocket--it was empty!He tried another pocket--there was nothing in that, either.He took off his coat and turned it upside down, shaking it--but not a single coin showed itself.And now, for the first time he remembered his first wish--to have always as much money in his pockets as Fat Ezekiel had in his.But all had vanished like smoke.

"So!here we are at the end of it all."

Meanwhile the landlord and Ezekiel sat staring at him in bewilderment, as he searched himself all over in vain to find some money somewhere.They refused to believe that he had none; and, at last, after they themselves had felt in his pockets, they grew angry, vowing that Gambling-Peter must be a magician who had transported all the money he had won together with his own to his house.Peter defended himself as best he could, but appearances were against him.Ezekiel vowed he would spread the shameful story all over the Black Forest; and the landlord declared he would go to town the first thing on the morrow, and denounce Peter as a sorcerer, and he would see to it, he added, that he was burnt at the stake as such.Whereupon they both fell on him in a fury, tore his clothes from his back, and flung him out into the road.

It was pitch-dark, not a star appearing in the sky, as Peter slunk homewards; but the misery which he suffered did not prevent him from recognising a dark form which strode along at his side, and which broke silence, at length, with the following words: "It is all up with you, Peter Munk; all your glory has come to an end; as I would have told you at first, if you had but listened to me instead of running off to that stupid Glassmanikin.Now you can see for yourself what is to be gained by despising my advice.Just try your luck with me for once, for I am very sorry for you in your present miserable condition.Nobody who comes to me ever repents having done so; and if you are not too afraid to come, I shall be awaiting you all day in the Pine-grove and you have only to call me, and I will come to you."

Peter knew well who it was thus addressing him.Seized with a sudden dread, he made no reply, but sped onwards to his home.

END OF PART I.

THE COLD HEART

PART II

On the Monday morning when Peter arrived at his Glassworks, he found not only his workpeople there, but also some very unwelcome visitors; these were the Bailiff and three of his myrmidons.The Bailiff greeted Peter with a "Good-morning," asked how he had slept, and then produced a lengthy document on which appeared the names of Peter's creditors.

"Can you settle or not?"demanded the official, with a keen glance at Peter."And make haste, please, for I have very little time to spare, as the tower-clock struck three some time ago."

Then Peter, in despair, had to confess that he had no more money in the world, and made over to the Bailiff for appraisement all his property, including factory, stock, stables, horses, wagons, etc.; and as the official and his men went round making an inventory of everything, he thought to himself: "The Pine-grove is not so far away; and as the Little One has not come to my aid, I'll try my luck with the Big One."And straightway he set off running for the Pine-grove as fast as if the officers of justice were at his heels.

As he passed the spot where he had first spoken to the Glassmanikin, he felt as though an invisible hand had caught hold of him; but he wrenched himself free, and ran on towards the ditch which, as he had had occasion to remember marked the boundary of Dutch Michael's domain, and no sooner did he spy it than he cried out with what breath he had left in his lungs: "Dutch Michael!Master Dutch Michael!"and immediately there stood before him the gigantic form of the raftsman, pole in hand.

"So, you've come!"cried Michael, with a laugh."Did they want to strip the skin from your back in order to sell it for the benefit of your creditors?Well, don't worry about it; as I have already told you, for your troubles you have to thank that sanctimonious little hypocrite, the Glassmanikin.When one gives at all, it should be with a lavish hand, and not stingily as is that niggard's wont.But come," he continued, turning towards the forest, "follow me to my house, and we will see if we cannot strike a bargain."

"Strike a bargain?"thought Peter."What can he get out of me?What have I to offer him?Must I serve him in some way; or what else will he require of me?"

At first, they climbed a steep incline which ended abruptly on the edge of a dark, deep, precipitous ravine.Dutch Michael sprang down from rock to rock as easily as down a broad staircase; and Peter nearly fainted with terror when he perceived how the form of the demon, as soon as the latter's foot had touched bottom, shot up to the height of a church steeple.Then the monster stretched forth an arm as long as a weaver's beam, and a hand as broad as a large table, crying out in a deep voice that sounded like a death-knell: "Stand on my hand and take hold of my fingers, so that you do not fall."Trembling all over, Peter did as he was bid, sitting down on the palm and steadying himself by grasping the gigantic thumb.

Deep down into the bowels of the earth he descended, but to Peter's surprise it grew no darker; on the contrary, the daylight seemed to become more and more intense in the ravine, until his eyes could scarcely bear the glare of it.

As Peter descended, Dutch Michael gradually decreased in size until when Peter had reached the ground the former had regained his normal stature, and there they stood before a house similar in all respects to those owned by well-to-do peasants in the Black Forest.The room, into which Peter was conducted, differed in no particular from the rooms of other Black Forest cottages, except that its appearance imparted a feeling of loneliness.The wooden clock hanging on the wall, the huge Dutch stove, the broad benches, the crockery arranged along the cornice were just as one might see anywhere.

Michael bade Peter take a seat at the great table, and then left the room, returning immediately with a jug of wine and glasses.He poured out some for Peter and himself, after which they sat and talked, Dutch Michael speaking of the joys of life, of foreign countries, of beautiful cities and rivers, until Peter became possessed of a longing to visit the same, and expressed his desire to the Dutchman.

And stretched forth an arm as long as a weaver's beam,

and a hand as broad as a large table.]

"But even if your whole frame were pulsating with the courage and energy to undertake something of the sort, would not a few beats of that foolish heart of yours set you all of a tremble at the prospect?And why should a sensible fellow such as you be troubled with such things as misfortune or wounded pride?The other day when they called you a cheat and a villain, was it in your head that you felt the disgrace?Did you get a pain in your stomach when the bailiff appeared just now and turned you out of doors?Come, tell me, where did you feel most anguish?"

"In my heart," Peter replied, pressing his hand on his throbbing breast; for he felt that his heart was turning over and over in his bosom.

"Now, don't be angry at what I am going to say--you have thrown away many a hundred guilders to beggars and other worthless people; and what profit has it brought you?They have showered blessings on your head, and wished you good health; but did you ever feel any better for that?Why, you could have kept a physician on half the money you thus wasted.A blessing, indeed--a fine blessing, now that they have seized your goods and turned you out!What was it that drove you to dive your hands into your pockets every time a beggarman stretched out his tattered hat to you?--Your heart it was, and always your heart; never your eyes, nor your tongue, your arms, nor your legs,--but your heart; you have always taken it too much to heart, as the saying is."

"But how can one manage to avoid it?I am trying all I can to suppress it, but my heart keeps on thumping and causing me anguish."

"By yourself, poor wretch that you are, you can do nothing," cried the other with a laugh; "but just let me take charge of the fluttering thing, and you will see how much more pleasant it will be."

"Give you my heart?"shrieked the horrified Peter."Why I should fall down dead on the spot!Not if I can help it!"

"Of course, if one of your master surgeons were to remove your heart, then you would die to a certainty; but with me it is quite another matter.But just come in here and satisfy yourself."

Saying which, he opened a door leading into another room, and bade Peter follow him.As the latter crossed the threshold his heart contracted convulsively, but he did not notice it, for the sight which now presented itself to him was too weird and amazing.On a number of wooden shelves stood glass-vessels filled with some transparent fluid, and in each of these was a human heart.Moreover, to every vessel was affixed a label upon which a name had been inscribed, several of which Peter's curiosity drove him to read.Here was the heart of the mayor of a neighbouring town; there, that of Fat Ezekiel; in the next vessel lay the heart of the Dance-King; further on, was the head-forester's heart.Here were also six hearts of well-known corn-brokers, eight belonging to conscription overseers, three to money lenders; in short, it was a collection of hearts of the most respected people in the district for twenty miles round.

"Look," said Dutch Michael, "all these people have shaken themselves free from the cares and troubles of life!These hearts beat anxiously and painfully no longer, and their original owners rejoice that they have been able to rid themselves of such restless companions."

"But what do they carry in their breasts in place of these?"asked Peter, who was quite faint with all that he had seen.

"This!" answered the other, as he took from a drawer a heart of stone

"What?"cried Peter, unable to repress a shudder which affected his entire frame."A heart of marble? But, if it is as you say, Master Dutch Michael, such a thing must feel very cold inside one's bosom."

"Not exactly cold, but quite pleasantly cool.Why should one's heart be warm?It doesn't keep you warm in winter--a good glass of spirits is far better for that purpose than a warm heart; while in summer, when it is so hot and close, you cannot think how cooling is the effect of such a heart as this.Besides which, as I have already told you, such a heart as this never throbs with anguish or terror, with foolish compassion or with any other emotion."

"And is that all that you have to give me?"asked Peter disappointedly."I hoped for money, and you offer me a stone!"

"Well, perhaps a hundred thousand guilders may satisfy you for a start.If you went the right way to work, you would soon be a millionaire."

"A hundred thousand?"cried the poor charcoal-burner in an ecstasy."There, don't beat so violently in my breast, we shall soon have done with one another.Good, Michael!give me the stone and the money, and you may relieve this habitation of its restless inmate."

"Ah, I was sure that you were a sensible fellow!"answered the Dutchman, smiling amiably."Come, we will have just one more glass, and then I will count out the money for you!"

Whereupon they returned to the other room, and sat down to their wine, drinking glass after glass, until Peter fell into a deep sleep.

* * * * *

Charcoal-Peter was awakened by the joyous fanfare of a posthorn, and behold he was sitting in a coach, which was bowling along a handsome broad highway, and when he leaned out of the window he could see the Black-Forest lying far behind him in the distance.At first he could not believe that it was he himself who could be thus sitting in this coach.His clothes were not the same that he had been wearing the day before; yet he remembered everything that had happened so clearly, that at last he doubted no longer, but cried out: "I am Charcoal-Peter, that's certain--Charcoal-Peter Munk and no other!"

He fell to wondering why it was that he could feel no regret, considering that, for the first time in his life, he had left the peaceful homestead and the forest where he had lived so long.Even when the thought of his mother occurred to him, helpless and wretched as she must be now, no tear came to his eyes, not a sigh escaped him--he felt so absolutely indifferent to everything."Truly," he muttered, "tears and sighs, homesickness and melancholy, all come from the heart; thanks to Dutch Michael, mine is cold and made of stone."

He laid his hand on his breast; all was still within; there was no movement whatever."If he has kept his word as to the hundred thousand guilders as he has with regard to my heart, I shall be quite content," he cried, beginning to examine everything in the coach.He found wearing apparel in such quantity and of such variety as he could possibly desire, but no money.At last he came upon a pocket in which he found many thousands of thalers in gold, besides bills drawn on business houses in all the great cities."Now I have got what I want," he thought, and he settled himself comfortably in a corner of the coach, as it drove onward into the wide world.

For two years Peter drove about everywhere, gazing to left and right from his coach at the houses as he passed them, and at the signboards of the inns at which he stopped, afterwards wandering about the towns, where everything that was worthy of note was shown to him.But he found pleasure in nought;--no picture, no building, no music, no dance,--nothing could move his heart of stone; his eyes and ears could no longer convey to him any sense of the beautiful.Nothing remained for him but to take what joy he could in eating, drinking, and sleeping; and thus he lived; travelling aimlessly about the world, eating, drinking for his sole entertainment, and sleeping his only escape from ennui.Now and then he would recollect how he had been happier when he was poor and had to work for his living.Then every beautiful vista over hill and vale had enchanted him, music and song had always delighted him, and he had found lasting enjoyment in the simple fare brought him by his mother as he sat by the charcoal pile.And as he pondered on the fact, he thought it very strange that now he could laugh at nothing, whereas, formerly, he had been wont to roar over the smallest joke.Now, when others laughed, he, for politeness' sake, distended his mouth, but there was no laughter in his heart.He perceived then that this outward tranquility of his brought no contentment.In the end it was not homesickness or melancholy which drove him homeward, but a depressing sense of solitude and joylessness.

As he drove over from Strasburg and came within view of the dark forest which was his home; when he saw for the first time since his departure the powerful frames, the friendly, trusty faces of the Black Foresters; as his ears caught the old familiar homely sounds, he put his hand to his heart, for his pulse beat more quickly, and he was sure that in another moment he must either rejoice or weep--but, how was it possible for him to be so foolish; had he not a heart of stone?

His first visit was to Dutch Michael, who welcomed him with all his old friendliness.

"Michael," he said to the latter, "I've been on my travels, and have seen everything; but it is all trash and humbug, and has only succeeded in boring me.Certainly, this stony thing of yours, which I bear in my bosom, saves me from much.I am never angry, and never sorrowful; but then I am never glad, and I feel as if I were only half alive.Cannot you put a little life into this stone heart?or, better still, give me back my old heart?It was my companion for five and twenty years, and if at times it did play me a bad turn, yet on the whole it was a merry and brave heart."

The forest spirit laughed grimly and bitterly.

"When you are dead, Peter Munk," he replied, "it will not fail you; then, indeed, will that soft, emotional heart be yours once more, and you will be able to feel whatever happens to you, joy or sorrow.But here on this earth it can never return to you!Yes, Peter, you have certainly been on your travels, but the way in which you lived was too aimless to be of any use to you.Settle down somewhere in the forest, build yourself a house, marry; set up in business--it is occupation of which you are in need; you were bored because you were idle, and yet you blamed it all upon this unoffending heart!"

Peter perceived that Michael was right in so far as his idleness was concerned, and determined to amass riches for himself.Michael gave him another hundred thousand guilders, and they parted good friends.

The story was soon spread throughout the Black-Forest that Charcoal-Peter Munk, or Gambling-Peter, had returned, this time richer than before.And it was the same as it is always: when he was reduced to beggary, they had thrust him from the door in broad daylight; but now, when he once more visited the inn one fine Sunday afternoon, they held out their hands to him, praised his horse, asked him about his travels, and when he sat down to play with Fat Ezekiel with thalers for points, he stood as high in their esteem as ever.He no longer engaged in glass-making, but in timber dealing, though this was merely a blind.His real business was corn-selling and money-lending.By degrees nearly half the Black Forest was in his debt; he lent money only at a ruinously high rate of interest, and sold corn only to the poor, to those who could not pay him cash down for it, at three times its value.He and the bailiff were now on the friendliest terms, and when anybody failed to pay Master Peter Munk to the very day, the bailiff and his myrmidons rode over, made an inventory of all the debtor's belongings and sold him up, driving father, mother and child out into the forest.At first, these proceedings caused the wealthy Peter some trouble; for the poor outcasts besieged his door, the men begging for time to pay, while their wives sought to move his stony heart by drawing his attention to their children, who were crying for bread.But after he had provided himself with one or two big and savage dogs, there was soon an end to these "cat's concerts," as he termed them.He had but to whistle and call his dogs, and the beggars fled, crying and screaming, in all directions.

His chief annoyance was the "old woman"--who was none other than Dame Munk, his own mother.She had lived in misery and want from the day when they had sold up her house and home; and now her son, though he had come back rich, no longer took any notice of her.Yet she, old, feeble and broken down, would come from time to time and stand, leaning on her stick, in front of his house.She did not now dare to enter, for he had once driven her out.But her greatest grief was that she was compelled to accept the charity of others in order to live, though her own son could have made her old age happy and free from care.But the cold heart was never touched at the sight of those pale well-known features, by their pleading expression, by the withered outstretched hand, by the frail and tottering form.When she knocked at the door on Saturdays he would draw sixpence from his pocket, grumbling the while, wrap it up in a piece of paper, and send a servant out to her with it.He caught the sound of her quavering voice as she spoke her thanks and wished him well on this earth; he heard her pant as she shuffled away from his door; then he thought no more of her except to regret that another sixpence had been so profitlessly expended.

At length Peter determined to marry.He knew well that any father in the Black Forest would be glad to let him wed his daughter; but he took pains over his choice, for he wanted everybody to praise his good luck and sense even in this matter.Wherefore he rode about on a round of inspection, visiting several houses in all parts of the forest; but none of the pretty Black Forest maidens seemed to be beautiful enough for him.At last, after having vainly attended all the dance-meetings in his search for a beautiful damsel, he heard one day that the loveliest and most virtuous of all the girls in the forest was the daughter of a poor woodcutter.

She lived quietly and alone, keeping house for her father, was clever and diligent, and never attended a dance, not even at Whitsuntide nor on Dedication Day.When Peter learnt of this jewel of the Black Forest, he resolved to marry her, and rode to the cottage which had been pointed out to him.The father of the lovely girl, whose name was Elspeth, received his distinguished visitor with surprise, but was even more astonished when he discovered that this was the wealthy Peter, and that he was anxious to become his son-in-law.He was not long making up his mind, for he considered that now there would be an end to all his troubles and poverty; therefore, without consulting Elspeth, he gave his consent; and the good child was so obedient that she became Dame Peter Munk without a murmur of dissent.

But it did not turn out so well for the poor girl as she had expected.She thought she knew how to keep house, but in nothing could she please Master Peter.She was sorry for poor people, and as her husband was a rich man, she considered it no crime to give a penny to a beggar-woman, or to offer an old man a "schnaps."But one day Master Peter, who had been watching her, spoke to her roughly and angrily: "Why are you wasting my fortune on rascals and vagabonds?Did you bring anything with you into the house that you might give away?In your father's house there was not enough broth to go round, and yet you are now throwing money about as if you were a princess!Let me catch you once more, and you shall feel the weight of my hand."

The lovely Elspeth wept in her room over her husband's ill-nature, and she often wished she were back again in her father's mean cottage instead of having to live in the house of the rich, avaricious and hard-hearted Peter.Even had she known that he had a heart of marble, and could never love anybody, not even herself, she would not have been so greatly surprised.Whenever she sat in the porch and a beggar passed by, taking off his hat and asking for alms, she shut her eyes in order not to see his wretchedness; she clenched her fist as if to keep her hand from straying against her will into her pocket in order to bestow a farthing or so.And so it came about that people throughout the forest began to speak despitefully of the beautiful Elspeth, saying that she was even more miserly than Peter Munk.

But one day Elspeth was sitting in front of the house, spinning and humming a little song, for she was in good spirits, the day was fine, and her husband, Peter, had ridden away across the country.And as she sat there, there came along the road a little old man, who was carrying a great heavy sack, and she could hear him panting from a long way off.Dame Elspeth regarded him sympathetically, thinking the while that such a little old man should not have to carry so heavy a burden.

Meanwhile the little man, panting and staggering, drew near, and as he passed Elspeth, he nearly broke down under the weight of the sack."Ah, have mercy, good lady, and give me a drink of water!"said the little man; "I can go no further, and feel ready to perish."

"But at your age you ought not to carry such a heavy load," said Elspeth.

Oh, have mercy, good lady and give a drink of water.

"But I must run errands; I am so poor, and I have to earn my living somehow," he replied."Surely so rich a lady as yourself can never know how hard it is to be poor, and how welcome would be a fresh drink on such a hot day."