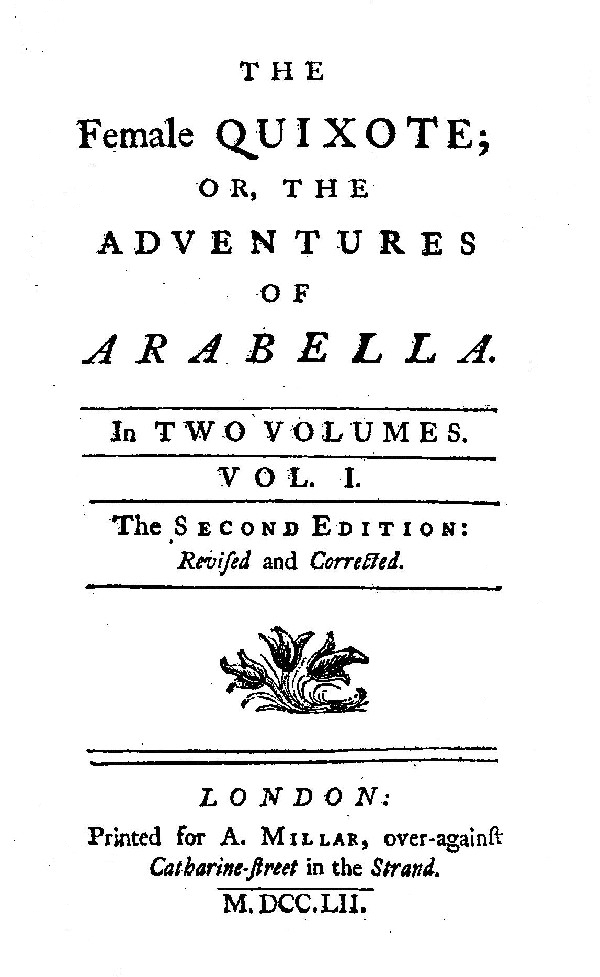

The Female Quixote; or, The Adventures of Arabella, v. 1-2

Play Sample

What do you say?cried Mr. Glanville, with a distracted look: Did you leave her in that condition in the fields?And was she not to be found when you came back?

No, indeed, sir, said Lucy, weeping; we could not find her, though we wandered about a long time.

Oh!Heavens!said he, walking about the room in a violent emotion, where can she be?What is become of her?Dear sister, pursued he, order somebody to saddle my horse: I'll traverse the country all night in quest of her.

You had best enquire, sir, said Lucy, if Edward is in the house: he knows, may be, where my lady is.

Who is he?cried Glanville.

Why the great man, sir, said Lucy, whom we thought to be a gardener, who came to carry my lady away; which made her get out of the house as fast as she could.

This is the strangest story, said Miss Glanville, that ever I heard: sure nobody would be so mad to attempt such an action; my cousin has the oddest whims!

Mr. Glanville, not able to listen any longer, charged Lucy to say nothing of this matter to any one; and then ran eagerly out of the room, ordering two or three of the servants to go in search of their lady: he then mounted his horse in great anguish of mind, not knowing whither to direct his course.

Chapter XI.

In which the lady is wonderfully delivered.

But to return to Arabella, whom we left in a very melancholy situation: Lucy had not been gone long from her before she opened her eyes; and, beginning to come perfectly to herself, was surprised to find her woman not near her: the moon shining very bright, she looked round her, and called Lucy as loud as she was able; but not seeing her, or hearing any answer, her fears became so powerful, that she had like to have relapsed into her swoon.

Alas!unfortunate maid that I am!cried she, weeping excessively, questionless I am betrayed by her on whose fidelity I relied, and who was acquainted with my most secret thoughts: she is now with my ravisher, directing his pursuit, and I have no means of escaping from his hands!Cruel and ungrateful wench, thy unparalleled treachery grieves me no less than all my other misfortunes: but why do I say her treachery is unparalleled?Did not the wicked Arianta betray her mistress into the power of her insolent lover?Ah!Arabella, thou art not single in thy misery, since the divine Mandana was, like thyself, the dupe of a mercenary servant.

Having given a moment or two to these sad reflections, she rose from the ground with an intention to walk on; but her ancle was so painful, that she could hardly move: her tears began now to flow with greater violence: she expected every moment to see Edward approach her; and was resigning herself up to despair, when a chaise, driven by a young gentleman, passed by her.Arabella, thanking Heaven for sending this relief, called out as loud as she could, conjuring him to stay.

The gentleman, hearing a woman's voice, stopped immediately, and asked what she wanted.

Generous stranger, said Arabella, advancing as well as she was able, do not refuse your assistance to save me from a most terrible danger: I am pursued by a person whom, for very urgent reasons, I desire to avoid.I conjure you, therefore, in the name of her you love best, to protect me; and may you be crowned with the enjoyment of all your wishes, for so charitable an action!

If the gentleman was surprised at this address, he was much more astonished at the beauty of her who made it: her stature, her shape, her inimitable complexion, the lustre of her fine eyes, and the thousand charms that adorned her whole person, kept him a minute silently gazing upon her, without having the power to make her an answer.

Arabella, finding he did not speak, was extremely disappointed.Ah!sir, said she, what do you deliberate upon?Is it possible you can deny so reasonable a request, to a lady in my circumstances?

For God's sake, madam, said the gentleman, alighting, and approaching her, let me know who you are, and how I can be of any service to you.

As for my quality, said Arabella, be assured it is not mean: and let this knowledge suffice at present.The service I desire of you is, to convey me to some place where I may be in safety for this night.To-morrow I will entreat you to let some persons, whom I shall name to you, know where I am; to the end they may take proper measures to secure me from the attempts of an insolent man, who has driven me from my own house, by the designs he was going to execute.

The gentleman saw there was some mystery in her case, which she did not choose to explain; and, being extremely glad at having so beautiful a creature in his power, told her she might command him in all she pleased; and helping her into the chaise, drove off as fast as he could; Arabella suffering no apprehensions from being alone with a stranger, since nothing was more common to heroines than such adventures; all her fears being of Edward, whom she fancied every moment she saw pursuing them: and, being extremely anxious to be in some place of safety, she urged her protector to drive as fast as possible; who, willing to have her at his own house, complied with her request; but was so unlucky in his haste, as to overturn the chaise.Though neither Arabella nor himself were hurt by the fall, yet the necessity there was to stay some time to put the chaise in a condition to carry them any farther, filled her with a thousand apprehensions, lest they should be overtaken.

In the mean time, the servants of Arabella, among whom Edward, not knowing how much he was concerned in her flight, was resolved to distinguish himself by his zeal in searching for her, had dispersed themselves about in different places: chance conducted Edward to the very spot where she was: when Arabella, perceiving him while he was two or three paces off, Oh!sir, cried she, behold my persecutor!Can you resolve to defend me against the violence he comes to offer me?

The gentleman, looking up, and seeing a man in livery approaching them, asked her, if that was the person she complained of; and if he was her servant?

If he is my servant, sir, replied she, blushing, he never had my permission to be so: and, indeed, no one else can boast of my having granted them such a liberty.

Do you know whose servant he is, then, madam?replied the gentleman, a little surprised at her answer, which he could not well understand.

You throw me into a great embarrassment, sir, resumed Arabella, blushing more than before: questionless, he appears to be mine; but, since, as I told you before, he never discovered himself to me, and I never permitted him to assume that title, his services, if ever I received any from him, were not at all considered by me as things for which I was obliged to him.

The gentleman, still more amazed at answers so little to the purpose, was going to desire her to explain herself upon this strange affair; when Edward, coming up close to Arabella, cried out in a transport, Oh!madam!thank God you are found.

Hold, impious man!said Arabella, and do not give thanks for that which, haply, may prove thy punishment.If I am found, thou wilt be no better for it: and, if thou continuest to persecute me, thou wilt probably meet with thy death, where thou thinkest thou hast found thy happiness.

The poor fellow, who understood not a word of this discourse, stared upon her like one that had lost his wits; when the protector of Arabella, approaching him, asked him, with a stern look, what he had to say to that lady, and why he presumed to follow her?

As the man was going to answer him, Mr. Glanville came galloping up; and Edward, seeing him, ran up to him, and informed him, that he had met with Lady Bella, and a gentleman, who seemed to have been overturned in a chaise, which he was endeavouring to refit; and that her ladyship was offended with him for coming up to her; and also, that the gentleman had used some threatening language to him upon that account.

Mr. Glanville, excessively surprised at what he heard, stopped; and, ordering a servant who came along with him to run back to the castle, and bring a chaise thither to carry Lady Bella home, he asked Edward several more questions relating to what she and the gentleman had said to him: and, notwithstanding his knowledge of her ridiculous humour, he could not help being alarmed by her behaviour, nor concluding that there was something very mysterious in the affair.

While he was thus conversing with Edward, Arabella, who had spied him almost as soon, was filled with apprehension to see him hold so quiet a parly with her ravisher: the more she reflected upon this accident, the more her suspicions increased; and, persuading herself at last, that Mr. Glanville was privy to his designs, this belief, however improbable, wrought so powerfully upon her imagination, that she could not restrain her tears.

Doubtless, said she, I am betrayed, and the perjured Glanville is no longer either my friend or lover: he is this moment concerting measures with my ravisher, how to deliver me into his power; and, like Philidaspes, is glad of an opportunity, by this treachery, to be rid of a woman whom his parents and hers had destined for his wife.

Mr. Glanville, having learned all he could from Edward, alighted; and giving him his horse to hold, came up to Arabella: and, after expressing his joy at meeting with her, begged her to let him know what accident had brought her, unattended, from the castle, at that time of night.

If by this question, said the incensed Arabella, you would persuade me you are ignorant of the cause of my flight, know, your dissimulation will not succeed; and that, having reason to believe you are equally guilty with him from whose intended violence I fled, I shall have recourse to the valour of this knight you see with me, to defend me, as well against you, as that ravisher, with whom I see you leagued.—Ah!unworthy cousin, pursued she, what dost thou propose to thyself by so black a treachery?What is to be the price of my liberty, which thou so freely disposest of?Has thy friend there, said she (pointing to Edward), a sister, or any relation, for whom thou barterest, by delivering me up to him?But assure thyself, this stratagem shall be of no use to thee: for, if thou art base enough to oppress my valiant deliverer with numbers, and thinkest by violence to get me into thy power, my cries shall arm heaven and earth in my defence.Providence may, haply, send some generous cavaliers to my rescue; and, if Providence fails me, my own hand shall give me freedom; for that moment thou offerest to seize me, that moment shall be the last of my life.

While Arabella was speaking, the young gentleman and Edward, who listened to her eagerly, thought her brain was disturbed: but Mr. Glanville was in a terrible confusion, and silently cursed his ill fate, to make him in love with a woman so ridiculous.

For Heaven's sake, cousin, said he, striving to repress some part of his disorder, do not give way to these extravagant notions: there is nobody intends to do you any wrong.

What!interrupted she, would you persuade me, that that impostor there, pointing to Edward, has not a design to carry me away; which you, by supporting him, are not equally guilty of?

Who?I!madam!cried out Edward: sure your ladyship does not suspect me of such a strange design!God knows I never thought of such a thing!

Ah!dissembler!interrupted Arabella, do not make use of that sacred name to mask thy impious falsehoods: confess with what intent you came into my father's service disguised.

I never came disguised, madam, returned Edward.

No!said Arabella: what means that dress in which I see you, then?

It is the marquis's livery, madam, said Edward, which he did not order to be taken from me when I left his service.

And with what purpose didst thou wear it?said she.Do not your thoughts accuse you of your crime?

I always hoped, madam——said he.

You hoped!interrupted Arabella, frowning.Did I ever give you reason to hope?I will not deny but I had compassion on you; but even that you was ignorant of.

I know, madam, you had compassion on me, said Edward; for your ladyship, I always thought, did not believe me guilty.

I was weak enough, said she, to have compassion on you, though I did believe you guilty.

Indeed, madam, returned Edward, I always hoped, as I said before (but your ladyship would not hear me out), that you did not believe any malicious reports; and therefore you had compassion on me.

I had no reports of you, said she, but what my own observation gave me; and that was sufficient to convince me of your fault.

Why, madam, said Edward, did your ladyship see me steal the carp then, which was the fault unjustly laid to my charge?

Mr. Glanville, as much cause as he had for uneasiness, could with great difficulty restrain laughter at this ludicrous circumstance; for he guessed what crime Arabella was accusing him of.As for the young gentleman, he could not conceive what she meant, and longed to hear what would be the end of such a strange conference.But poor Arabella was prodigiously confounded at his mentioning so low an affair; not being able to endure that Glanville and her protector should know a lover of hers could be suspected of so base a theft.

The shame she conceived at it, kept her silent for a moment: but, recovering herself at last, No, said she, I knew you better than to give any credit to such an idle report: persons of your condition do not commit such paltry crimes.

Upon my soul, madam, said the young gentleman, persons of his condition often do worse.

I don't deny it, sir, said Arabella; and the design he meditated of carrying me away was infinitely worse.

Really, madam, returned the gentleman, if you are such a person as I apprehend, I don't see how he durst make such an attempt.

It is very possible, sir, said she, that I might be carried away, though I was of greater quality than I am: were not Mandana, Candace, Clelia, and many other ladies who underwent the same fate, of a quality more illustrious than mine?

Really, madam, said he, I know none of these ladies.

No, sir!said Arabella, extremely mortified.

Let me entreat you, cousin, interrupted Glanville (who feared this conversation would be very tedious), to expose yourself no longer to the air at this time of night: suffer me to conduct you home.

It concerns my honour, said she, that this generous stranger should not think I am the only one that was ever exposed to these insolent attempts.You say, sir, pursued she, that you don't know any of these ladies I mentioned before: let me ask you, then, if you are acquainted with Parthenissa, or Cleopatra, who were both for some months in the hands of their ravishers?

As for Parthenissa, madam, said he, neither have I heard of her: nor do I remember to have heard of any more than one Cleopatra: but she was never ravished, I am certain; for she was too willing.

How!sir, said Arabella: was Cleopatra ever willing to run away with her ravisher?

Cleopatra was a whore, was she not, madam?said he.

Hold thy peace, unworthy man, said Arabella; and profane not the memory of that fair and glorious queen, by such injurious language: that queen, I say, whose courage was equal to her beauty; and her virtue surpassed by neither.Good heavens!what a black defamer have I chosen for my protector!

Mr. Glanville, rejoicing to see Arabella in a disposition to be offended with her new acquaintance, resolved to soothe her a little, in hopes of prevailing upon her to return home.Sir, said he to the gentleman, who could not conceive why the lady should so warmly defend Cleopatra, you were in the wrong to cast such reflections upon that great queen, (repeating what he had heard his cousin say before): for all the world, pursued he, knows she was married to Julius Cæsar.

Though I commend you, said Arabella, for taking the part of a lady so basely vilified; yet let not your zeal for her honour induce you to say more than is true for its justification; for thereby you weaken, instead of strengthening, what may be said in her defence.One falsehood always supposes another, and renders all you can say suspected; whereas pure, unmixed truth, carries conviction along with it, and never fails to produce its desired effect.

Suffer me, cousin, interrupted Glanville, again to represent to you, the inconveniency you will certainly feel, by staying so late in the air: leave the justification of Cleopatra to some other opportunity; and take care of your own preservation.

What is it you require of me?said Arabella.

Only, resumed Glanville, that you would be pleased to return to the castle, where my sister, and all your servants, are inconsolable for your absence.

But who can assure me, answered she, that I shall not, by returning home, enter voluntarily into my prison?The same treachery which made the palace of Candace the place of her confinement, may turn the castle of Arabella into her gaol.For, to say the truth, I still more than suspect you abet the designs of this man; since I behold you in his party, and ready, no doubt, to draw your sword in his defence: how will you be able to clear yourself of this crime?Yet I will venture to return to my house, provided you will swear to me, you will offer me no violence, with regard to your friend there: and also I insist, that he, from this moment, disclaim all intentions of persecuting me, and banish himself from my presence for ever.Upon this condition I pardon him, and will likewise pray to Heaven to pardon him also.Speak, presumptuous unknown, said she to Edward, wilt thou accept of my pardon upon the terms I offer it thee?And wilt thou take thyself to some place where I may never behold thee again?

Since your ladyship, said Edward, is resolved not to receive me into your service, I shan't trouble you any more: but I think it hard to be punished for a crime I was not guilty of.

It is better, said Arabella, turning from him, that thou shouldst complain of my rigour, than the world tax me with lightness and indiscretion.And now, sir, said she to Glanville, I must trust myself to your honour, which I confess I do a little suspect; but, however, it is possible you have repented, like the poor prince Thrasybulus, when he submitted to the suggestions of a wicked friend, to carry away the fair Alcionida, whom he afterwards restored.Speak, Glanville, pursued she, are you desirous of imitating that virtuous prince, or do you still retain your former sentiments?

Upon my word, madam, said Glanville, you will make me quite mad, if you go on in this manner: pray let me see you safe home; and then, if you please, you may forbid my entrance into the castle, if you suspect me of any bad intentions towards you.

It is enough, said she, I will trust you.As for you, sir, speaking to the young gentleman, you are so unworthy, in my apprehensions, by the calumnies you have uttered against a person of that sex which merits all your admiration and reverence, that I hold you very unfit to be a protector of any of it: therefore I dispense with your services upon this occasion; and think it better to trust myself to the conduct of a person, who, like Thrasybulus, by his repentance, has restored himself to my confidence, than to one, who, though indeed he has never betrayed me, yet seems very capable of doing so, if he had the power.

Saying this, she gave her hand to Glanville, who helped her into the chaise that was come from the castle; and the servant, who brought it, mounting his horse, Mr. Glanville drove her home, leaving the gentleman, who, by this time, had refitted his chaise, in the greatest astonishment imaginable at her unaccountable behaviour.

BOOK III.

Chapter I.

Two conversations, out of which the reader may pick up a great deal.

Arabella, continuing to ruminate upon her adventure during their little journey, appeared so low-spirited and reserved, that Mr. Glanville, though he ardently wished to know all the particulars of her flight and meeting with that gentleman, whose company he found her in, was obliged to suppress his curiosity for the present, out of a fear of displeasing her.As soon as they alighted at the castle, her servants ran to receive her at the gates, expressing their joy to see her again, by a thousand confused exclamations.

Miss Glanville, being at her toilet when she heard of her arrival, ran down to welcome her, in her hurry forgetting, that as her woman had been curling her hair, she had no cap on.

Arabella received her compliments with a little coolness; for, observing that her grief for her absence had not made her neglect any of her usual solicitude about her person, she could not perceive it had been very great: therefore, when she had made some slight answer to the hundred questions she asked in a breath, she went up to her apartment; and, calling Lucy, who was crying with joy for her return, she questioned her strictly concerning her leaving her in the fields, acknowledging to her that she suspected her fidelity, though she wished at the same time she might be able to clear herself.

Lucy, in her justification, related, after her punctual way, all that had happened: by which Arabella was convinced she had not betrayed her; and was also in some doubt whether Mr. Glanville was guilty of any design against her.

Since, said she to Lucy, thou art restored to my good opinion, I will, as I have always done, unmask my thoughts to thee. I confess then, with shame and confusion, that I cannot think of Mr. Glanville's assisting the unknown to carry me away, without resenting a most poignant grief: questionless, my weakness will surprise thee; and could I conceal it from myself, I would from thee; but, alas! it is certain that I do not hate him; and I believe I never shall, guilty as he may be in my apprehensions.

Hate him!madam, said Lucy: God forbid you should ever hate Mr. Glanville, who, I am sure, loves your ladyship as well as he does his own sister!

You are very confident, Lucy, said Arabella blushing, to mention the word love to me: if I thought my cousin had bribed thee to it, I should be greatly incensed: however, though I forbid you to talk of his passion, yet I permit you to tell me the violence of his transports when I was missing; the threats he uttered against my ravishers; the complaints he made against fortune; the vows he offered for my preservation; and, in fine, whatever extravagances the excess of his sorrow forced him to commit.

I assure you, madam, said Lucy, I did not hear him say any of all this.

What!interrupted Arabella: and didst thou not observe the tears trickle from his eyes, which, haply, he strove to conceal?Did he not strike his bosom with the vehemence of his grief; and cast his accusing and despairing eyes to Heaven, which had permitted such a misfortune to befall me?

Indeed, madam, I did not, resumed Lucy; but he seemed to be very sorry; and said he would go and look for your ladyship.

Ah!the traitor!interrupted Arabella in a rage: fain would I have found out some excuse for him, and justified him in my apprehensions; but he is unworthy of these favourable thoughts.Speak of him no more, I command you: he is guilty of assisting my ravisher to carry me away; and therefore merits my eternal displeasure.But though I could find reasons to clear him even of that crime, yet he is guilty of indifference and insensibility for my loss, since he neither died with grief at the news of it; nor needed the interposition of his sister, or the desire of delivering me, to make him live.

Arabella, when she had said this, was silent; but could not prevent some tears stealing down her fair face: therefore, to conceal her uneasiness, or to be at more liberty to indulge it, she ordered Lucy to make haste and undress her; and, going to bed, passed the small remainder of the night, not in rest, which she very much needed, but in reflections on all the passages of the preceding day; and finding, or imagining she found, new reasons for condemning Mr. Glanville, her mind was very far from being at ease.

In the morning, lying later than usual, she received a message from Mr. Glanville, enquiring after her health; to which she answered, that he was too little concerned in the preservation of it, to make it necessary to acquaint him.

Miss Glanville soon after sent to desire permission to drink her chocolate by her bed-side; which, as she could not in civility refuse, she was very much perplexed how to hide her melancholy from the eyes of that discerning lady, who, she questioned not, would interpret it in favour of her brother.

Upon Miss Glanville's appearance, she forced herself to assume a cheerful look, asking her pardon for receiving her in bed; and complaining of bad rest, which had occasioned her lying late.

Miss Glanville, after answering her compliments with almost equal politeness, proceeded to ask her an hundred questions concerning the cause of her absence from the castle: Your woman, pursued she, laughing, told us a strange medley of stuff about a great man, who was a gardener; and wanted to carry you away.Sure there was nothing in it!Was there?

You must excuse me, cousin, said Arabella, if I do not answer your questions precisely now: it is sufficient that I tell you, certain reasons obliged me to act in the manner I did, for my own preservation; and that, another time, you shall know my history; which will explain many things you seem to be surprised at, at present.

Your history!said Miss Glanville.Why, will you write your own history then?

I shall not write it, said Arabella; though, questionless, it will be written after my death.

And must I wait till then for it?resumed Miss Glanville, gaily.

No, no, interrupted Arabella: I mean to gratify your curiosity sooner; but it will not be yet a good time; and, haply, not till you have acquainted me with yours.

Mine!said Miss Glanville: it would not be worth your hearing; for really I have nothing to tell, that would make an history.

You have, questionless, returned Arabella, gained many victories over hearts; have occasioned many quarrels between your servants, by favouring some one more than the others: probably you have caused some bloodshed; and have not escaped being carried away once or twice: you have also, I suppose, undergone some persecution from those who have the disposal of you, in favour of a lover whom you have an aversion to; and lastly, there is haply some one among your admirers, who is happy enough not to be hated by you.

I assure you, interrupted Miss Glanville, I hate none of my admirers; and I can't help thinking you very unkind to use my brother as you do: I am sure, there is not one man in an hundred that would take so much from your hands as he does.

Then there is not one man in an hundred, resumed Arabella, whom I should think worthy to serve me.But pray, madam, what ill usage is it your brother complains of?I have treated him with much less severity than he had reason to expect; and, notwithstanding he had the presumption to talk to me of love, I have endured him in my sight; an indulgence for which I may haply be blamed in after-ages.

Why, sure, Lady Bella, said Miss Glanville, it would be no such crime for my brother to love you!

But it was a mortal crime to tell me so, interrupted Arabella.

And why was it such a mortal crime to tell you so?said Miss Glanville.Are you the first woman by millions, that has been told so?

Doubtless, returned Arabella, I am the first woman of my quality, that ever was told so by any man, till after an infinite number of services, and secret sufferings: and truly I am of the illustrious Mandana's mind; for she said, that she should think it an unpardonable presumption, for the greatest king on earth to tell her he loved her, though after ten years of the most faithful services, and concealed torments.

Ten years!cried out Miss Glanville, in amazement; did she consider what alterations ten years would make in her face, and how much older she would be at the end of ten years, than she was before?

Truly, said Arabella, it is not usual to consider such little matters so nicely; one never has the idea of an heroine older than eighteen, though her history begins at that age; and the events which compose it contain the space of twenty more.

But, dear cousin, resumed Miss Glanville, do you resolve to be ten years a-courting?Or rather, will you be loved in silence ten years, and be courted the other ten; and so marry when you are an old woman?

Pardon me, cousin, resumed Arabella; I must really find fault with the coarseness of your language.Courting, and old woman!What strange terms!Let us, I beseech you, end this dispute: if you have any thing to say in justification of your brother, which, I suppose, was the chief intention of your visit, I shall not be rude enough to restrain you; though I could wish you would not lay me under the necessity of hearing what I cannot persuade myself to believe.

Since, returned Miss Glanville, I know of no crime my brother has been guilty of, I have nothing to say in his justification: I only know, that he is very much mortified at the message you sent him this morning; for I was with him when he received it.But pray, what has he done to offend you?

If Mr. Glanville, interrupted Arabella, hopes for my pardon, he must purchase it by his repentance, and a sincere confession of his fault; which you may much better understand from himself, than from me: and, for this purpose, I will condescend to grant him a private audience, at which I desire you would be present; and also, I should take it well, if you will let him know, that he owes this favour wholly to your interposition.

Miss Glanville, who knew her brother was extremely desirous of seeing Arabella, was glad to accept of these strange terms; and left her chamber, in order to acquaint him with that lady's intentions.

Chapter II.

A solemn interview.

In the mean time, that fair-one being risen, and negligently dressed, as was her custom, went into her closet, sending to give Miss Glanville notice that she was ready to see her.This message immediately brought both the brother and the sister to her apartment: and Miss Glanville, at her brother's request, staying in the chamber, where she busied herself in looking at her cousin's jewels, which lay upon the toilet, he came alone into the closet, in so much confusion at the thoughts of the ridiculous figure he made in complying with Arabella's fantastical humours, that his looks persuading her there was some great agitation in his mind, she expected to see him fall at her feet, and endeavour to deprecate her wrath by a deluge of tears.

Mr. Glanville however disappointed her in that respect; for, taking a seat near her, he began to entreat her, with a smiling countenance, to tell him in what he had offended her; protesting, that he was not conscious of doing or saying any thing to displease her.

Arabella was greatly confused at this question, which she thought she had no reason to expect; it not being possible for her to tell him she was offended, that he was not in absolute despair for her absence, without, at the same time, confessing she looked upon him in the light of a lover whose expressions of a violent passion would not have displeased her: therefore, to disengage herself from the perplexity his question threw her into, she was obliged to offer some violence to her ingenuousness; and, contrary to her real belief, tax him again with a design of betraying her into the power of the unknown.

Mr. Glanville, though excessively vexed at her persisting in so ridiculous an error, could hardly help smiling at the stern manner in which she spoke; but, knowing of what fatal consequence it would be to him, if he indulged any gaiety in so solemn a conference, he composed his looks to a gravity suitable to the occasion; and asked her in a very submissive tone, what motive she was pleased to assign for so extraordinary a piece of villainy, as that she supposed him guilty of?

Truly, answered she blushing, I do not pretend to account for the actions of wicked and ungenerous persons.

But, madam, resumed Glanville, if I must needs be suspected of a design to seize upon your person, methinks it would have been more reasonable to suppose I would rather use that violence in favour of my own pretensions, than those of any other whatever; for, though you have expressly forbid me to tell you I love you, yet I hope you still continue to think I do.

I assure you, returned Arabella, assuming a severe look, I never gave myself the trouble to examine your behaviour with care enough to be sensible if you still were guilty of the weakness which displeased me; but, upon a supposition that you repented of your fault, I was willing to live with you upon terms of civility and friendship, as became persons in that degree of relationship in which we are: therefore, if you are wise, you will not renew the remembrance of those follies I have long since pardoned; nor seek occasions of offending me by new ones of the same kind, lest it produce a more severe sentence than that I formerly laid upon you.

However, madam, returned Mr. Glanville, you must suffer me to assure you, that my own interest, which was greatly concerned in your safety, and my principles of honour, would never allow me to engage in so villainous an enterprise, as that of abetting any person in stealing you away: nor can I conceive how you possibly could imagine a fellow who was your menial servant could form so presumptuous and dangerous a design.

By your manner of speaking, resumed Arabella, one would imagine you were really ignorant, both of the quality of that presumptuous man, as well as his designed offence: but yet, it is certain, I saw you in his company; and saw you ready to draw your sword in his defence, against my deliverer.Had I not the evidence of my own senses for your guilt, I must confess I could not be persuaded of it by any other means: therefore, since appearances are certainly against you, it is not strange if I cannot consent to acquit you in my apprehensions, till I have more certain confirmation of your innocence, than your bare testimony only; which, at present, has not all the weight with me it had some time ago.

I protest, madam, said Mr. Glanville, who was strangely perplexed, I have reason to think my case extremely hard, since I have brought myself to be suspected by you, only through my eagerness to find you, and solicitude for your welfare.

Doubtless, interrupted Arabella, if you are innocent, your case is extremely hard; yet it is not singular; and therefore you have less reason to complain: the valiant Coriolanus, who was the most passionate and faithful lover imaginable, having, by his admirable valour, assisted the ravishers of his adored Cleopatra, against those who came to rescue her; and, by his arm alone, opposed to great numbers of their enemies, facilitated the execution of their design, had the mortification afterwards to know, that he had all that time been fighting against that divine princess, who loaded him with the most cruel reproaches for the injury he had done her: yet fortune was so kind as to give him the means of repairing his fault, and restoring him to some part of her good opinion; for, covered with wounds as he was, and fatigued with fighting before, yet he undertook, in that condition, to prevent her ravishers from carrying her off; and, for several hours, continued fighting alone with near two hundred men, who were not able to overcome him, notwithstanding his extreme weariness, and the multitude of blows which they aimed at him: therefore, Glanville, considering you, as Cleopatra did that unfortunate prince, who was before suspected by her, as neither guilty nor innocent, I can only, like her, wish you may find some occasion of justifying yourself from the crime laid to your charge. Till then, I must be under a necessity of banishing you from my presence, with the same consolatory speech she used to that unfortunate prince:—"Go, therefore, Glanville, go, and endeavour your own justification: I desire you should effect it no less than you do yourself; and, if my prayers can obtain from Heaven this favour for you, I shall not scruple to offer some in your behalf."

Chapter III.

In which the interview is ended, not much to the lover's satisfaction, but exactly conformable to the rules of romance.

Arabella, when she had pronounced these words, blushed excessively, thinking she had said too much: but, not seeing any signs of extreme joy in the face of Glanville, who was silently cursing Cleopatra, and the authors of those romances that had ruined so noble a mind; and exposed him to perpetual vexations, by the unaccountable whims they had raised—Why are you not gone, said she, while I am in an humour not to repent of the favour I have shown you?

You must excuse me, cousin, said Mr. Glanville, peevishly, if I do not think so highly as you do of the favour.Pray how am I obliged to you for depriving me of the pleasure of seeing you, and sending me on a wild-goose chase, after occasions to justify myself of a crime I am wholly innocent of, and would scorn to commit?

Though, resumed Arabella, with great calmness, I have reason to be dissatisfied with the cool and unthankful manner in which you receive my indulgence, yet I shall not change the favourable disposition I am in towards you, unless you provoke me to it by new acts of disobedience: therefore, in the language of Cleopatra, I shall tell you——

Upon my soul, madam, interrupted Glanville, I have no patience with that rigorous gipsy, whose example you follow so exactly, to my sorrow: speak in your own language, I beseech you; for I am sure neither hers, nor any one's upon earth, can excel it.

Yet, said Arabella, striving to repress some inclination to smile at this sally, notwithstanding your unjust prohibitions, I shall make use of the language of that incomparable lady, to tell you my thoughts; which are, that it is possible you might be sufficiently justified in my apprehensions, by the anxiety it now appears you had for my safety, by the probability which I find in your discourse, and the good opinion I have of you, were it not requisite to make your innocence apparent to the world, that so it might be lawful for Arabella to readmit you, with honour, into her former esteem and friendship.

Mr. Glanville, seeing that it would be in vain to attempt to make her alter her fantastical determination at this time, went out of the closet without deigning to make any reply to his sentence, though delivered in the language of the admirable Cleopatra: but his ill-humour was so visible in his face, that Arabella, who mistook it for an excess of despair, could not help feeling some kind of pity for the rigour which the laws of honour and romance obliged her to use him with.And while she sat meditating upon the scene which had just passed, Mr. Glanville returned to his own room, glad that his sister, not being in Arabella's chamber, where he had left her, had no opportunity of observing his discontent, which she would not fail to enquire the cause of.

Here he sat, ruminating upon the follies of Arabella, which he found grew more glaring every day: every thing furnished matter for some new extravagance; her character was so ridiculous, that he could propose nothing to himself but eternal shame and disquiet, in the possession of a woman for whom he must always blush and be in pain.But her beauty had made a deep impression on his heart: he admired the strength of her understanding; her lively wit; the sweetness of her temper; and a thousand amiable qualities which distinguished her from the rest of her sex: her follies, when opposed to all those charms of mind and person, seemed inconsiderable and weak; and though they were capable of giving him great uneasiness, yet they could not lessen a passion which every sight of her so much the more confirmed.

As he feared it was impossible to help loving her, his happiness depended upon curing her of her romantic notions; and, though he knew not how to effect such a change in her as was necessary to complete it, yet he would not despair, but comforted himself with hopes of what he had not courage to attempt.Sometimes he fancied company, and an acquaintance with the world, would produce the alteration he wished: yet he dreaded to see her exposed to ridicule by her fantastical behaviour, and become the jest of persons who were not possessed of half her understanding.

While he traversed his chamber, wholly engrossed by these reflections, Miss Glanville was entertaining Sir George, of whose coming she was informed while she was in Arabella's chamber.

Chapter IV.

In which our heroine is greatly disappointed.

Miss Glanville, supposing her brother would be glad not to be interrupted in his conference with Lady Bella, did not allow any one to acquaint them with Sir George's visit; and telling the baronet her cousin was indisposed, had by these means all his conversation to herself.

Sir George, who ardently wished to see Lady Bella, protracted his visit, in hopes that he should have that satisfaction before he went away.And that fair lady, whose thoughts were a little discomposed by the despair she apprehended Mr. Glanville was in, and fearful of the consequences, when she had sat some time after he left her, ruminating upon what had happened, quitted her closet, to go and enquire of Miss Glanville in what condition his mind seemed to be when he went away; for she never doubted but that he was gone, like Coriolanus, to seek out for some occasion to manifest his innocence.

Hearing, therefore, the voice of that lady, who was talking and laughing very loud in one of the summer parlours, and being terrified with the apprehension that it was her brother with whom she was thus diverting herself, she opened the door of the room precipitately; and by her entrance, filled Sir George with extreme pleasure; while her unexpected sight produced a quite contrary effect on Miss Glanville.

Arabella, eased of her fear that it was Mr. Glanville, who, instead of dying with despair, was giving occasion for that noisy laugh of his sister, saluted the baronet with great civility; and, turning to Miss Glanville, I must needs chide you, said she, for the insensibility with which it appears you have parted with your brother.

Bless me, madam, interrupted Miss Glanville, what do you mean?Whither is my brother gone?

That, indeed, I am quite ignorant of, resumed Arabella; and I suppose he himself hardly knows what course he shall take: but he has been with you, doubtless, to take his leave.

Take his leave!repeated Miss Glanville: has he left the castle so suddenly then, and gone away without me?

The enterprise upon which he is gone, said Arabella, would not admit of a lady's company: and, since he has left so considerable an hostage with me as yourself, I expect he will not be long before he return; and, I hope, to the satisfaction of us both.

Miss Glanville, who could not penetrate into the meaning of her cousin's words, began to be strangely alarmed: but presently supposing she had a mind to divert herself with her fears, she recovered herself, and told her she would go up to her brother's chamber, and look for him.

Arabella did not offer to prevent her, being very desirous of knowing whether he had not left a letter for her upon his table, as was the custom in those cases: and, while she was gone, Sir George seized the opportunity of saying an hundred gallant things to her, which she received with great indifference; the most extravagant compliments being what she expected from all men: and provided they did not directly presume to tell her they loved her, no sort of flattery or adulation could displease her.

In the mean time, Miss Glanville having found her brother in his chamber, repeated to him what Lady Bella had said, as she supposed, to fright her.

Mr. Glanville, hearing this, and that Sir George was with her, hastened to them as fast as possible, that he might interrupt the foolish stories he did not doubt she was telling.

Upon Miss Glanville's appearance with her brother, Arabella was astonished.

I apprehended, sir, said she, that you were some miles from the castle by this time: but your delay and indifference convince me, you neither expect nor wish to find the means of being justified in my opinion.

Pray, cousin, interrupted Glanville (speaking softly to her) let us leave this dispute to some other time.

No, sir, resumed she, aloud; my honour is concerned in your justification: nor is it fit I should submit to have the appearance of amity for a person who has not yet sufficiently cleared himself of a crime, with too much reason laid to his charge.Did Coriolanus, think you, act in this manner?Ah!if he had, doubtless, Cleopatra would never have pardoned him: nor will I any longer suffer you to give me repeated causes of discontent.

Sir George, seeing confusion in Mr. Glanville's countenance, and rage in Arabella's, began to think, that what he had at first taken for a jest, was a serious quarrel between them, at which it was not proper he should be present; and was preparing to go: when Arabella, stopping him with a graceful action—

If, noble stranger, said she, you are so partial to the failings of a friend, that you will undertake to defend any unjustifiable action he may be guilty of, you are at liberty to depart: but if you will promise to be an unprejudiced hearer of the dispute between Mr. Glanville and myself, you shall know the adventure which has given rise to it; and will be judge of the reasonableness of the commands I have laid on him.

Though, madam, said Sir George (bowing very low to her), Mr. Glanville is my friend, yet there is no likelihood I shall espouse his interest against yours: and a very strong prepossession I feel in favour of you, already persuades me that I shall give sentence on your side, since you have honoured me so far as to constitute me judge of this difference.

The solemn manner in which Sir George (who began to suspect Lady Bella's peculiar turn) spoke this, pleased her infinitely; while Mr. Glanville, vexed as he was, could hardly forbear laughing: when Arabella, after a look of approbation to Sir George, replied—

I find I have unwillingly engaged myself to more than I first intended: for, to enable you to judge clearly of the matter in dispute, it is necessary you should know my whole history.

Mr. Glanville, at this word, not being able to constrain himself, uttered a groan of the same nature with those which are often heard in the pit at the representation of a new play.Sir George understood him perfectly well; yet seemed surprised: and Arabella, starting up—

Since, said she, I have given you no new cause of complaint, pray, from whence proceeds this increase of affliction?

I assure you, cousin, answered he, my affliction, if you please to term it so, increases every day; and I believe it will make me mad at last: for this unaccountable humour of yours is not to be borne.

You do not seem, replied Arabella, to be far from madness already: and if your friend here, upon hearing the passages between us, should pronounce you guilty, I shall be at a loss whether I ought to treat you as a madman or a criminal.Sir, added she, turning to Sir George, you will excuse me, if, for certain reasons, I can neither give you my history myself, nor be present at the relation of it.One of my women, who is most in my confidence, shall acquaint you with all the particulars of my life: after which I expect Mr. Glanville will abide by your decision, as, I assure myself, I shall be contented to do.

Saying this, she went out of the parlour, in order to prepare Lucy for the recital she was to make.

Mr. Glanville, resolving not to be present at this new absurdity, ran out after her; and went into the garden, with a strong inclination to hate the lovely visionary who gave him such perpetual uneasiness; leaving his sister alone with the baronet, who diverted herself extremely with the thoughts of hearing her cousin's history; assuring the baronet, that he might expect something very curious in it, and find matter sufficient to laugh at; for she was the most whimsical woman in the world.

Sir George, who resolved to profit by the knowledge of her foible, made very little reply to Miss Glanville's sneers; but waited patiently for the promised history, which was much longer coming than he imagined.

Chapter V.

Some curious instructions for relating an history.

Arabella, as soon as she left them, went up to her apartment; and calling Lucy into her closet, told her that she had made choice of her, since she was best acquainted with her thoughts, to relate her history to her cousins, and a person of quality who was with them.

Sure your ladyship jests with me, said Lucy: how can I make a history about your ladyship?

There is no occasion, replied Arabella, for you to make a history: there are accidents enough in my life to afford matter for a long one: all you have to do is to relate them as exactly as possible.You have lived with me from my childhood, and are instructed in all my adventures; so that you must be certainly very capable of executing the task I have honoured you with.

Indeed, said Lucy, I must beg your ladyship will excuse me.I never could tell how to repeat a story when I have read it; and I know it is not such simple girls as I can tell histories: it is only fit for clerks, and such sort of people, that are very learned.

You are learned enough for that purpose, said Arabella; and if you make so much difficulty in performing this part of your duty, pray how came you to imagine you were fit for my service, and the distinction I have favoured you with?Did you ever hear of any woman that refused to relate her lady's story, when desired?Therefore, if you hope to possess my favour and confidence any longer, acquit yourself handsomely of this task, to which I have preferred you.

Lucy, terrified at the displeasure she saw in her lady's countenance, begged her to tell her what she must say.

Well!exclaimed Arabella: I am certainly the most unfortunate woman in the world!Every thing happens to me in a contrary manner from any other person!Here, instead of my desiring you to soften those parts of my history where you have greatest room to flatter; and to conceal, if possible, some of those disorders my beauty has occasioned; you ask me to tell you what you must say; as if it was not necessary you should know as well as myself, and be able not only to recount all my words and actions, even the smallest and most inconsiderable, but also all my thoughts, however instantaneous; relate exactly every change of my countenance; number all my smiles, half-smiles, blushes, turnings pale, glances, pauses, full-stops, interruptions; the rise and falling of my voice; every motion of my eyes; and every gesture which I have used for these ten years past; nor omit the smallest circumstance that relates to me.

Lord bless me, madam!said Lucy, excessively astonished: I never, till this moment, it seems, knew the hundredth thousandth part of what was expected from me.I am sure, if I had, I would never have gone to service; for I might well know I was not fit for such slavery.

There is no such great slavery in doing all I have mentioned to you, interrupted Arabella: it requires, indeed, a good memory, in which I never thought you deficient; for you are punctual to the greatest degree of exactness in recounting every thing one desires to hear from you.

Lucy, whom this praise soothed into good humour, and flattered with a belief that she was able, with a little instruction, to perform what her lady required, told her if she pleased only to put her in a way how to tell her history, she would engage, after doing it once, to tell it again whenever she was desired.

Arabella, being obliged to comply with the odd request, for which there was no precedent in all the romances her library was stuffed with, began to inform her in this manner:

First, said she, you must relate my birth, which you know is very illustrious; and because I am willing to spare you the trouble of repeating things that are not absolutely necessary, you must apologize to your hearers for slipping over what passed in my infancy, and the first eight or ten years of my life; not failing, however, to remark, that, from some sprightly sallies of imagination, at those early years, those about me conceived marvellous hopes of my future understanding: from thence you must proceed to an accurate description of my person.

What, madam!interrupted Lucy, must I tell what sort of person you have, to people who have seen you but a moment ago?

Questionless you must, replied Arabella; and herein you follow the examples of all the squires and maids who relate their masters' and ladies' histories: for though it be to a brother, or near relation, who has seen them a thousand times, yet they never omit an exact account of their persons.

Very well, madam, said Lucy: I shall be sure not to forget that part of my story.I wish I was as perfect in all the rest.

Then, Lucy, you must repeat all the conversations I have ever held with you upon the subjects of love and gallantry, that your audience may be so well acquainted with my humour, as to know exactly, before they are told, how I shall behave, in whatever adventures befall me.—After that, you may proceed to tell them how a noble unknown saw me at church; how prodigiously he was struck with my appearance; the tumultuous thoughts that this first view of me occasioned in his mind.—

Indeed, madam, interrupted Lucy again, I can't pretend to tell his thoughts: for how should I know what they were?None but himself can tell that.

However that may be, said Arabella, I expect you should decypher all his thoughts as plainly as he himself could do; otherwise my history will be very imperfect.Well, I suppose you are at no loss about that whole adventure, in which you yourself bore so great a share; so I need not give you any further instructions concerning it: only you must be sure, as I said before, not to omit the least circumstance in my behaviour, but relate every thing I did, said, and thought, upon that occasion.The disguised gardener must appear next in your story: here you will of necessity be a little deficient, since you are not able to acquaint your hearers with his true name and quality; which, questionless, is very illustrious.However, above all, I must charge you not to mention that egregious mistake about the carp; for you know how—

Here Miss Glanville's entrance put a stop to the instructions Lucy was receiving: for she told Arabella that Sir George was gone.

How!returned she, is he gone?Truly I am not much obliged to him for the indifference he has showed to hear my story.

Why, really, madam, said Miss Glanville, neither of us expected you would be as good as your word, you were so long in sending your woman down: and my brother persuaded Sir George you were only in jest; and Sir George has carried him home to dinner.

And is it at Sir George's, replied Arabella, that your brother hopes to meet with an occasion of clearing himself?He is either very insensible of my anger, or very conscious of his own innocence.

Miss Glanville, having nothing to say in answer to an accusation she did not understand, changed the discourse: and the two ladies passed the rest of the day together, with tolerable good humour on Miss Glanville's side; who was in great hopes of making a conquest of the baronet, before whom Arabella had made herself ridiculous enough.But that lady was far from being at ease; she had laid herself under a necessity of banishing Mr. Glanville, if he did not give some convincing proof of his innocence; which, as matters stood, she thought would be very hard for him to procure; and, as she could not absolutely believe him guilty, she was concerned she had gone so far.

Chapter VI.

A very heroic chapter.

Mr. Glanville, coming home in the evening, a little elevated with the wine of which he had drank too freely at Sir George's, being told the ladies were together, entered the room where they were sitting; and, beholding Arabella, whose pensiveness had given an enchanting softness to her face, with a look of extreme admiration—

Upon my soul, cousin, said he, if you continue to treat me so cruelly, you'll drive me mad.How I could adore you this moment, added he, gazing passionately at her, if I might but hope you did not hate me!

Arabella, who did not perceive the condition he was in, was better pleased with this address than any he had ever used; and, therefore, instead of chiding him as she was wont, for the freedom of his expressions, she cast her bright eyes upon the ground with so charming a confusion, that Glanville, quite transported, threw himself on his knees before her; and, taking her hand, attempted to press it to his lips: but she, hastily withdrawing it—

From whence is this new boldness?said she.And what is it you would implore by that prostrate posture?I have told you already upon what conditions I will grant you my pardon.Clear yourself of being an accomplice with my designed ravisher, and I am ready to restore you to my esteem.

Let me perish, madam, returned Glanville, if I would not die to please you, this moment!

It is not your death that I require, said she: and though you should never be able to justify yourself in my opinion, yet you might, haply, expiate your crime, by a less punishment than death.

What shall I do, then, my angelic cousin?resumed he.

Truly, said she, the sense of your offence ought so mortally to afflict you, that you should invent some strange kind of penance for yourself, severe enough to prove your penitence sincere.—You know, I suppose, what the unfortunate Orontes did, when he found he had wronged his adored Thalestris by an injurious suspicion.

I wish he had hanged himself!said Mr. Glanville, rising up in a passion, at seeing her again in her altitudes.

And why, pray, sir, said Arabella, are you so severe upon that poor prince; who was, haply, infinitely more innocent than yourself?

Severe, madam!said Glanville, fearing he had offended her: why, to be sure, he was a sad scoundrel to use his adored Thalestris as he did: and I think one cannot be too severe upon him.

But, returned Arabella, appearances were against her; and he had some shadow of reason for his jealousy and rage: then, you know, amidst all his transports, he could not be prevailed upon to draw his sword against her.

What did that signify?said Glanville: I suppose he scorned to draw his sword upon a woman: that would have been a shame indeed.

That woman, sir, resumed Arabella, was not such a contemptible antagonist as you think her: and men, as valiant, possibly, as Orontes (though, questionless, he was one of the most valiant men in the world) have been cut in pieces by the sword of that brave Amazon.

Lord bless me!said Miss Glanville, I should be afraid to look at such a terrible woman: I am sure she must be a very masculine sort of creature.

You are much mistaken, miss, said Arabella: for Thalestris, though the most stout and courageous of her sex, was, nevertheless, a perfect beauty; and had as much harmony and softness in her looks and person, as she had courage in her heart, and strength in her blows.

Indeed, madam, returned Miss Glanville, you can never persuade me, that a woman who can fight, and cut people to pieces with her blows, can have any softness in her person: she must needs have very masculine hands, that could give such terrible blows: and I can have no notion of the harmony of a person's looks, who, by what you say, must have the heart of a tiger.But, indeed, I don't think there ever could be such a woman.

What, miss!interrupted Arabella: do you pretend to doubt that there ever was such a person as Thalestris, queen of the Amazons?Does not all the world know the adventures of that illustrious princess; her affection for the unjust Orontes, who accused her of having a scandalous intrigue with Alexander, whom she went to meet with a very different design, upon the borders of her kingdom?The injurious letter he wrote her, upon this suspicion, made her resolve to seek for him all over the world, to give him that death he had merited, by her own hand: and it was in those rencounters that he had with her, while she was thus incensed, that he forbore to defend himself against her, though her sword was often pointed to his breast.

But, madam, interrupted Mr. Glanville, pray what became of this queen of the Amazons?Was she not killed at the siege of Troy?—She never was at the siege of Troy, returned Arabella: but she assisted the princes who besieged Babylon, to recover the liberty of Statira and Parisatis: and it was in the opposite party that she met with her faithless lover.

If he was faithless, madam, said Mr. Glanville, he deserved to die: and I wish, with all my soul, she had cut him in pieces with that famous sword of hers that had done such wonders.

Yet this faithless man, resumed Arabella, whom you seem to have such an aversion to, gave so glorious a proof of his repentance and sorrow, that the fair queen restored him to her favour, and held him in much dearer affection than ever: for, after he was convinced of her innocence, he was resolved to punish himself with a rigour equal to the fault he had been guilty of; and, retiring to the woods, abandoned for ever the society of men; dwelling in a cave, and living upon bitter herbs, passing the days and nights in continual tears and sorrow for his crime.And here he proposed to end his life, had not the fair Thalestris found him out in this solitude; and, struck with the sincerity of his repentance, pardoned him; and, as I have said before, restored him to her favour.

And to show you, said Glanville, that I am capable of doing as much for you, I will, if you insist upon it, seek out for some cave, and do penance in it, like that Orontes, provided you will come and fetch me out of it, as that same fair queen did him.

I do not require so much of you, said Arabella; for I told you before, that, haply, you are justified already in my opinion; but yet it is necessary you should find out some method of convincing the world of your innocence; otherwise it is not fit I should live with you upon terms of friendship and civility.

Well, well, madam, said Glanville, I'll convince you of my innocence, by bringing that rascal's head to you, whom you suspect I was inclined to assist in stealing you away.

If you do that, resumed Arabella, doubtless you will be justified in my opinion, and the world's also; and I shall have no scruple to treat you with as much friendship as I did before.

My brother is much obliged to you, madam, interrupted Miss Glanville, for putting him upon an action that would cost him his life!

I have so good an opinion of your brother's valour, said Arabella, that I am persuaded he will find no difficulty in performing his promise; and I make no question but I shall see him covered with the spoils of that impostor, who would have betrayed me; and I flatter myself, he will be in a condition to bring me his head, as he bravely promises, without endangering his own life.

Does your ladyship consider, said Miss Glanville, that my brother can take away no person's life whatever, without endangering his own?

I consider, madam, said Arabella, your brother as a man possessed of virtue and courage enough to undertake to kill all my enemies and persecutors, though I had ever so many; and I presume he would be able to perform as many glorious actions for my service, as either Juba, Cæsario, Artamenes, or Artaban, who, though not a prince, was greater than any of them.

If those persons you have named, said Miss Glanville, were murderers, and made a practice of killing people, I hope my brother will be too wise to follow their examples: a strange kind of virtue and courage indeed, to take away the lives of one's fellow-creatures!How did such wretches escape the gallows, I wonder?

I perceive, interrupted Arabella, what kind of apprehensions you have: I suppose you think, if your brother was to kill my enemy, the law would punish him for it: but pray undeceive yourself, miss.The law has no power over heroes; they may kill as many men as they please, without being called to any account for it; and the more lives they take away, the greater is their reputation for virtue and glory.The illustrious Artaban, from the condition of a private man, raised himself to the sublimest pitch of glory by his valour; for he not only would win half a dozen battles in a day; but, to show that victory followed him wherever he went, he would change parties, and immediately the vanquished became conquerors; then, returning to the side he had quitted, changed the laurels of his former friends into chains.He made nothing of tumbling kings from their thrones, and giving away half a dozen crowns in a morning; for his generosity was equal to his courage; and to this height of power did he raise himself by his sword.Beginning at first with petty conquests, and not disdaining to oppose his glorious arm to sometimes less than a score of his enemies; so, by degrees, inuring himself to conquer inconsiderable numbers, he came at last to be the terror of whole armies, who would fly at the sight of his single sword.

This is all very astonishing indeed, said Miss Glanville.However, I must entreat you not to insist upon my brother's quarrelling and fighting with people, since it will be neither for your honour nor his safety; for I am afraid, if he was to commit murder to please you, the laws would make him suffer for it; and the world would be very free with its censures on your ladyship's reputation, for putting him upon such shocking crimes.

By your discourse, miss, replied Arabella, one would imagine you knew as little in what the good reputation of a lady consists, as the safety of a man; for certainly the one depends entirely upon his sword, and the other upon the noise and bustle she makes in the world.The blood that is shed for a lady enhances the value of her charms; and the more men a hero kills, the greater his glory; and, by consequence, the more secure he is.If to be the cause of a great many deaths can make a lady infamous, certainly none were ever more so than Mandana, Cleopatra, and Statira, the most illustrious names in antiquity; for each of whom, haply, an hundred thousand men were killed: yet none were ever so unjust as to profane the virtue of those divine beauties, by casting any censures upon them for these glorious effects of their charms, and the heroic valour of their admirers.

I must confess, interrupted Miss Glanville, I should not be sorry to have a duel or two fought for me in Hyde-Park; but then I would not have any blood shed for the world.

Glanville here interrupting his sister with a laugh, Arabella also could not forbear smiling at the harmless kind of combats her cousin was fond of.

But to put an end to the conversation, and the dispute which gave rise to it, she obliged Mr. Glanville to promise to fight with the impostor Edward, whenever he found him; and either take away his life, or force him to confess he had no part in the design he had meditated against her.

This being agreed upon, Arabella, conducting Miss Glanville to her chamber, retired to her own; and passed the night with much greater tranquillity, than she had done the preceding; being satisfied with the care she had taken of her own glory, and persuaded that Glanville was not unfaithful—a circumstance that was of more consequence to her happiness than she was yet aware of.

Chapter VII.

In which our heroine is suspected of insensibility.

While these things passed at the castle, Sir George was meditating on the means he should use to acquire the esteem of Lady Bella, of whose person he was a little enamoured, but of her fortune a great deal more.

By the observations he had made on her behaviour, he discovered her peculiar turn: he was well read in romances himself, and had actually employed himself some weeks in giving a new version of the Grand Cyrus; but the prodigious length of the task he had undertaken terrified him so much that he gave it over: nevertheless, he was perfectly well acquainted with the chief characters in most of the French romances; could tell every thing that was borrowed from them in all the new novels that came out; and, being a very accurate critic, and a mortal hater of Dryden, ridiculed him for want of invention, as it appeared by his having recourse to these books for the most shining characters and incidents in his plays.Almanzor, he would say, was the copy of the famous Artaban in Cleopatra, whose exploits Arabella had expatiated upon to Miss Glanville, and her brother: his admired character of Melantha in Marriage A-la-mode, was drawn from Berissa in the Grand Cyrus; and the story of Osmyn and Bensayda, in his Conquest of Granada, taken from Sesostris and Timerilla in that romance.

Fraught therefore with the knowledge of all the extravagances and peculiarities in those books, he resolved to make his addresses to Arabella in the form they prescribed; and, not having delicacy enough to be disgusted with the ridicule in her character, served himself with her foible, to effect his designs.

It being necessary, in order to his better acquaintance with Arabella, to be upon very friendly terms with Miss Glanville and her brother, he said a thousand gallant things to one, and seemed so little offended with the gloom he observed upon the countenance of the other, who positively assured him, that Arabella meant only to laugh at him, when she promised him her history, that he entreated him, with the most obliging earnestness, to favour him with his company at his house, where he omitted no sort of civility, to confirm their friendship and intimacy; and persuaded him, by several little and seemingly unguarded expressions, that he was not so great an admirer of Lady Bella, as her agreeable cousin Miss Glanville.

Having thus secured a footing in the castle, he furnished his memory with all the necessary rules of making love in Arabella's taste, and deferred his next visit no longer than till the following day; but Mr. Glanville being indisposed, and not able to see company, he knew it would be in vain to expect to see Arabella, since it was not to be imagined Miss Glanville could admit of a visit, her brother being ill; and Lady Bella must be also necessarily engaged with her.

Contenting himself, therefore, with having enquired after the health of the two ladies, he returned home, not a little vexed at his disappointment.

Mr. Glanville's indisposition increasing every day, grew at last dangerous enough to fill his sister with extreme apprehensions.Arabella, keeping up to her forms, sent regularly every day to enquire after his health; but did not offer to go into his chamber, though Miss Glanville was almost always there.

As she conceived his sickness to be occasioned by the violence of his passion for her, she expected some overture should be made her by his sister, to engage her to make him a visit; such a favour being never granted by any lady to a sick lover, till she was previously informed her presence was necessary to hinder the increase of his distemper.

Miss Glanville would not have failed to represent to her cousin the incivility and carelessness of her behaviour, in not deigning to come and see her brother in his indisposition, had not Mr. Glanville, imputing this neglect to the nicety of her notions, which he had upon other occasions experienced, absolutely forbid her to say any thing to her cousin upon this subject.

Miss Glanville being thus forced to silence, by the fear of giving her brother uneasiness, Arabella was extremely disappointed to find, that, in five days illness, no application had been made to her, either by the sick lover, or his sister, who she thought interested herself too little in his recovery; so that her glory obliging her to lay some constraint upon herself, she behaved with a coolness and insensibility that increased Miss Glanville's aversion to her, while, in reality, she was extremely concerned for her cousin's illness; but not supposing it dangerous, since they had not recourse to the usual remedy, of beseeching a visit from the person whose presence was alone able to work a cure, she resolved to wait patiently the event.

However, she never failed in her respect to Miss Glanville, whom she visited every morning before she went to her brother; and also constantly dined with her in her own apartment, enquiring always, with great sweetness, concerning her brother's health; when perceiving her in tears one day, as she came in, as usual, to dine with her, she was extremely alarmed; and asked with great precipitation if Mr. Glanville was worse.

He is so bad, madam, returned Miss Glanville, that I believe it will be necessary to send for my papa, for fear he should die, and he not see him.

Die, miss!interrupted Arabella eagerly: No, he must not die; and shall not, if the pity of Arabella is powerful enough to make him live.Let us go then, cousin, said she, her eyes streaming with tears; let us go and visit this dear brother, whom you lament: haply the sight of me may repair the evils my rigour has caused him; and since, as I imagine, he has forborne, through the profound respect he has for me, to request the favour of a visit, I will voluntarily bestow it on him, as well for the affection I bear you, as because I do not wish his death.

You do not wish his death, madam!said Miss Glanville, excessively angry at a speech, in her opinion, extremely insolent.Is it such a mighty favour, pray, not to wish the death of my brother, who never injured you?I am sure, your behaviour has been so extremely inhuman, that I have repented a thousand times we ever came to the castle.

Let us not waste the time in idle reproaches, said Arabella.If my rigour has brought your brother into this condition, my compassion can draw him out of it: it is no more than what all do suffer, who are possessed of a violent passion; and few lovers ever arrive to the possession of their mistresses, without being several times brought almost to their graves, either by their severity or some other cause.But nothing is more easy than to work a cure in these cases; for the very sight of the person beloved sometimes does it, as it happened to Artamenes, when the divine Mandana condescended to visit him: a few kind words, spoken by the fair princess of Persia to Oroondates, recalled him from the gates of death; and one line from Parisatis's hand, which brought a command to Lysimachus to live, made him not only resolve, but even able, to obey her.—

Miss Glanville, quite out of patience at this tedious harangue, without any regard to ceremony, flounced out of the room; and ran to her brother's chamber, followed by Arabella, who imputed her rude haste to a suspicion that her brother was worse.

Chapter VIII.

In which we hope the reader will be differently affected.

At their entrance into the room, Miss Glanville enquired of the physician, just going out, how he found her brother?Who replied, that his fever was increased since last night, and that it would not (seeing Arabella preparing to go to his bed-side) be proper to disturb him.

Saying this, he bowed, and went out; and Miss Glanville, repeating what the physician had said, begged her to defer speaking to him till another time.

I know, said she, that he apprehends the sight of me will cause so many tumultuous motions in the soul of his patient, as may prove prejudicial to him: nevertheless, since his disorder is, questionless, more in his mind than body, I may prove, haply, a better physician than he; since I am more likely than he, to cure an illness I have caused—

Saying this, she walked up to Mr. Glanville's bed-side, who, seeing her, thanked her in a weak voice, for coming to see him; assuring her, he was very sensible of the favour she did him—

You must not, said she, blushing, thank me too much, lest I think the favour I have done you is really of more consequence than I imagined, since it merits so many acknowledgments.Your physician tells us, pursued she, that your life is in danger; but I persuade myself you will value it so much from this moment, that you will not protract your cure any longer.

Are you mad, madam, whispered Miss Glanville, who stood behind her, to tell my brother that the physician says he is in danger?I suppose you really wish he may die, or you would not talk so.

If, answered she, whispering again to Miss Glanville, you are not satisfied with what I have already done for your brother, I will go as far as modesty will permit me: and gently pulling open the curtains—

Glanville, said she, with a voice too much raised for a sick person's ear, I grant to your sister's solicitations, what the fair Statira did to an interest yet more powerful; since, as you know it was her own brother, who pleaded in favour of the dying Orontes: therefore, considering you in a condition haply no less dangerous than that of that passionate prince, I condescend, like her, to tell you that I do not wish your death; that I entreat you to live; and, lastly, by all the power I have over you, I command you to recover.

Ending these words, she closed the curtain, that her transported lover might not see her blushes and confusion, which were so great, that, to conceal them, even from Miss Glanville, she hurried out of the room, and retired to her own apartment, expecting in a little time, to receive a billet, under the sick man's hand, importing, that in obedience to her commands, he was recovered, and ready to throw himself at her feet, to thank her for that life she had bestowed upon him, and to dedicate the remains of it to her service.

Miss Glanville, who stayed behind her in a strange surprise at her ridiculous behaviour, though she longed to know what her brother thought of it, finding he continued silent, would not disturb him.The shame he conceived at hearing so absurd a speech from a woman he passionately loved; and the desire he had, not to hear his sister's sentiments upon it; made him counterfeit sleep, to avoid any discourse with her upon so disagreeable a subject.