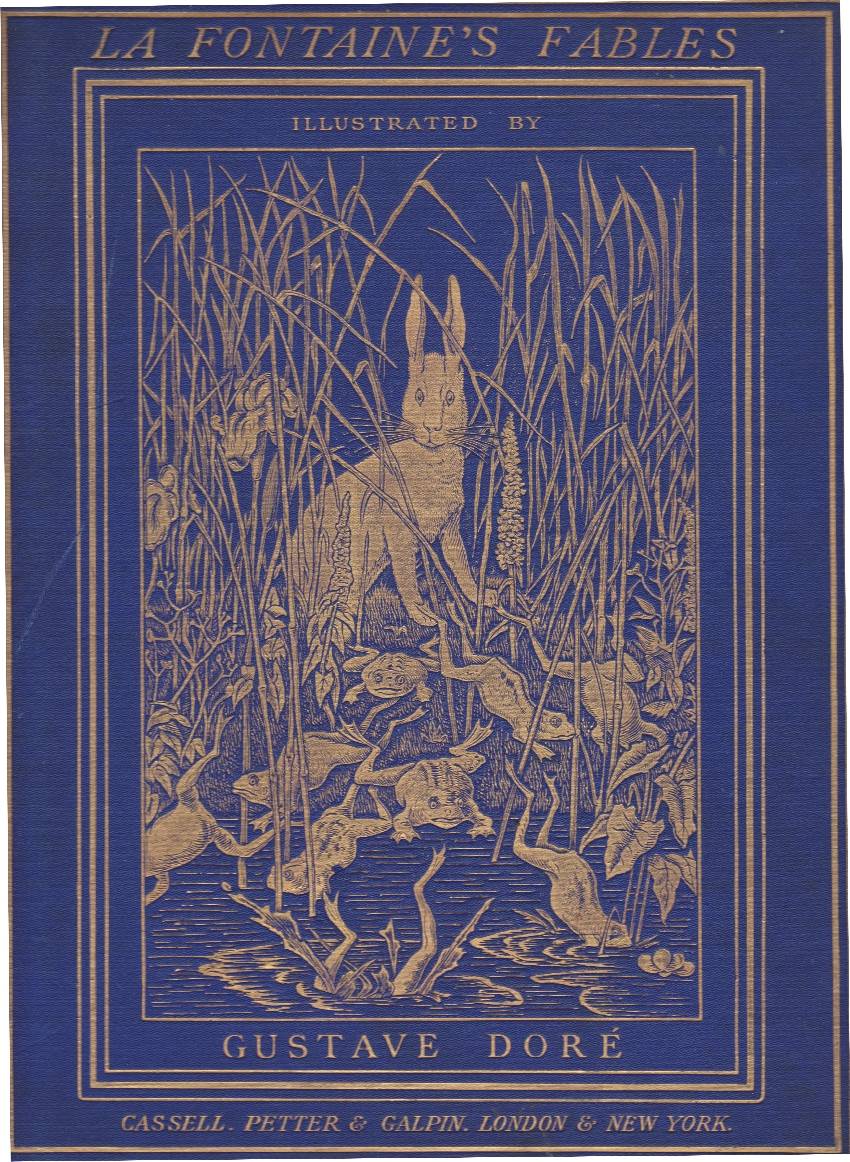

The Fables of La Fontaine / Translated into English Verse by Walter Thornbury and Illustrated by Gustave Doré

Play Sample

[1] The chronology of our worthy La Fontaine is here at fault, for between the times of Æsop and Planudes there was an interval of nearly twenty centuries; Æsop having flourished in the sixth century before Christ, and Planudes having lived in the fourteenth century of the Christian era.

[2] This life of Æsop, composed by a monk of the fourteenth century, is a legend which has replaced history by disfiguring it. If we confine ourselves exclusively to the testimonies of the ancients, we shall be able to tell in a few words all that has come down to us that is at all likely to be true respecting the life of Æsop. Although various authors have attributed his birth-place in turn to Mesembria in Thrace, to Samos, and to Sardis in Lydia, it is almost certain that he was born in Phrygia, either at Amorium, or in another city of the same province named Cotisium. The deformity which has been attributed to him is simply an exaggeration of a certain ugliness of countenance; and as he also stammered, he has been declared to have been almost dumb. The first portion of his life was passed in slavery, at first under the Lydian philosopher Xantus, and then under Iadmo at Samos, where he had for a companion the celebrated courtesan, Rhodope. Having been freed by Iadmo, he went to the court of Crœsus, where he enjoyed great favour. Employed by this prince to convey his presents to the temple at Delphi, and certain liberalities to the inhabitants, the perfidy and resentment of the people, whom he had not deemed worthy of his master's gifts, were the cause of his death. He was accused of having stolen a sacred vase which had been treacherously concealed amongst his goods. Both gods and men avenged his death. His journeys to Babylon and in Egypt are pure inventions. If we may believe Plutarch, he was present at the banquet of the Seven Wise Men at Corinth. The contradictory accounts given by authors as to the place of his birth may be explained by his many journeys; for he has been said to have been born wherever he resided. It will be seen by this brief sketch, that the life of Æsop by Planudes is not a pure invention, and that we may say with respect to it—

"However great the lie may he.

Therein some grains of truth we see."

[3] In the lists of the Kings of Babylon there is found no monarch of this name, and this is another proof amongst many that the life of Æsop by Planudes is a fiction.

[4] The Athenians erected a statue to Æsop, which was the work of the celebrated Lysippus, and it was placed opposite those of the Seven Wise Men.

DEDICATION

TO

MONSEIGNEUR THE DAUPHIN[1]

MONSEIGNEUR,

If there be anything ingenious in the republic of letters, it may be said that it is the manner in which Æsop has deduced his moral.It were truly to be wished that other hands than mine had added to the fable the ornaments of poetry, since the wisest of the ancients[2] has decided that they are not useless. I venture, Monseigneur, to submit to you certain attempts in this manner, as being not altogether unsuited to your earlier years. You are of an age[3] at which amusements and sports are allowed to princes; but at the same time you should devote some portion of your attention to serious reflections. This is precisely what we meet with in the fables which we owe to Æsop. At first sight they appear puerile; but their puerility is only the covering of important truths.

I do not doubt, Monseigneur, that you entertain a favourable opinion of compositions which are at once so useful and so agreeable; for what more can one desire than the useful and the agreeable?It is these that have been the means of introducing knowledge amongst men.Æsop has discovered the singular art of joining the one to the other.The perusal of his works invariably plants in the soul the seeds of virtue, and teaches it to know itself, without letting it feel that it is pursuing a study, whilst, in fact, it even believes that it is otherwise engaged.It is a means of instruction which has been happily made use of by him whom His Majesty has selected as your tutor.[4] He teaches you all that a prince should learn in such a manner that you study not only without trouble, but even with pleasure. We hope much from this; but, to tell the truth, there are things from which we hope infinitely more, and those, Monseigneur, are the qualities which our invincible monarch has bestowed upon you by the mere circumstance of your birth, and the example which he gives you day by day. When you see him forming such grand designs; when you see him calmly regarding the agitation of Europe and the efforts which it makes to divert him from his enterprises;[5] when you see him penetrating by a single effort the heart of one province[6] bristling against him with insurmountable obstacles, and subjugating another[7] within eight days, during that season which is the most hostile of all others to the operations of war, and when the courts of other princes are redolent only of peace and pleasure; when you see him not content with merely subduing men, but resolved also to vanquish the elements; and when, I say, on his return from this expedition, in which he has conquered like another Alexander, you see him ruling his people like another Augustus,—admit, Monseigneur, that, in spite of the tenderness of your years, you sigh for glory as ardently as your father, and that you await with impatience the moment when you will be able to declare yourself his rival in your worship of this divine mistress. But, no; you do not await it, Monseigneur; you anticipate it; and in proof of this I need no other witnesses than that noble restlessness, that vivacity, that ardour, those many evidences of spirit, of courage, of greatness of soul, which you so continually display. It must, doubtless, be the greatest gratification to our monarch, as it is a most agreeable spectacle to the universe, to see you thus growing up, a young plant which will one day protect with its shadow peoples and nations.

I might enlarge upon this subject.But as the plan I have proposed to myself of amusing you is more suited to my powers than that of praising you, I shall hasten to have recourse to my fables, and will add to the truths I have told you but this—and that is, Monseigneur, that I am, with respectful zeal, your very humble, very obedient, and very faithful servant,

DE LA FONTAINE.

[1] Louis, Dauphin of France, son of Louis XIV. , and of Marie Theresa of Austria, was born at Fontainebleau on the 1st of November, 1661, and died at Meudon on the 14th of April, 1671.

[2] Socrates.

[3] The Dauphin was six years and five months old when La Fontaine published the collection of fables to which this Dedication is prefixed. It was completed on the 3rd of March, 1668.

[4] Monseigneur the Dauphin had two tutors: the first being M. the President de Perigni, and the second M. Bossuet, the Bishop of Meaux. La Fontaine, in the above passage, alludes to M. de Perigni.

[5] This refers to the Triple Alliance formed between England, Spain, and Holland, for the purpose of checking the conquests of the French monarch.

[6] Flanders, in which the French king made a campaign in 1667, when he took Douai, Tournoi, Oudenarde, Ath, Alost, and Lille.

[7] Franche-Comté, which he subdued in 1668.

PREFACE.

The indulgence with which some of my fables have been received[1] has induced me to hope that this present collection may meet with the same favour. At the same time I must admit that one of the masters of our eloquence[2] has disapproved of the plan of rendering these fables in verse, since he believes that their chief ornament consists in having none; and that, moreover, the restraints of poetry, added to the severity of our language, would frequently embarrass me, and deprive most of these narratives of that brevity which may be styled the very soul of the art of story-telling, since without it a tale necessarily becomes tame and languid. This opinion could only have been expressed by a man of exquisite taste, and I will merely ask of him that he will in some degree relax it, and will admit that the Lacedemonian graces are not so entirely opposed to the French language, that it is impossible to make them accord.

After all, I have but followed the example, I will not say of the ancients, which would not affect me in this case, but that of the moderns.In every age, amongst every poetical people, Parnassus has deemed this species of composition its own. Æsop's fables had scarcely seen the light, when Socrates[3] thought proper to dress them in the livery of the Muses; and what Plato says on this subject is so pleasant, that I cannot refrain from making it one of the ornaments of this Preface. He says, then, that Socrates having been condemned to death, his punishment was respited on account of the occurrence of certain fêtes. Cébès went to see him on the day of his death, and Socrates then told him that the gods had several times warned him by dreams that he should devote himself to music before he died. He did not at first understand the signification of these dreams; for, as music does not improve a man's moral nature, of what use could it be to him?[4] It was evident, however, that there was some mystery involved, for the gods never ceased to give him the same warning, and it had come to him again on the occasion of one of the fêtes to which I have above alluded. At length, after having deeply reflected on what it might be that Heaven intended him to do, he concluded that as music and poetry are so closely allied, it probably meant him to turn his attention to the latter. There can be no good poetry without harmony; but to good poetry fiction is also equally necessary, and Socrates only knew how to tell the truth. At length, however, he discovered a compromise; selecting such fables as those of Æsop, which always contain something of truth in them, he employed the last moments of his life in rendering them into verse.

Socrates is not the only one who has regarded fables and poetry as sisters.Phædrus has also declared that he held this opinion, and by the excellence of his work we are able to judge of that of the philosopher.After Phædrus, Avienus treated the same subject in the same way; finally, the moderns have also followed their example, and we find instances of this not only amongst foreign nations, but in our own. It is true, that when our own countrymen devoted their attention to this species of composition, the French language was so different from what it now is, that we may regard them in this case as foreigners. This has not deterred me from my enterprise. On the contrary, I have flattered myself with the hope that, if I did not pursue this career with success, I should at least earn the credit of having opened the road.

It may possibly happen that my labours will induce others to continue the work; and, indeed, there is no reason why this species of composition should be exhausted until there shall remain no fresh fables to put in verse.I have selected the best; that is to say, those which seem to me to be so; but, in addition to the fact that I may have erred in my selection, it will be by no means a difficult thing for others to give a different rendering even to those which I have selected; and if their renderings should be briefer than mine, they will doubtless be more approved.In any case, some praise will always be due to me, either because my rashness has had a happy result, and that I have not departed too far from the right path, or, at least, because I shall have instigated others to do better.

I think that I have sufficiently justified my design.As regards the execution, I shall leave the public to be the judge.There will not be found in my renderings the elegance and extreme brevity which are the charms of Phædrus, for these qualities are beyond my powers; and that being the case, I have thought it right to give more ornament to my work than he has done.I do not blame him for having restricted himself in length, for the Latin language enabled him to be brief; and, indeed, if we take the trouble to examine closely, we shall find in this author all the genuine characteristics and genius of Terence.The simplicity of these great men is magnificent; but, not possessing the powers of language of these authors, I cannot attain their heights.I have striven, therefore, to compensate in some degree for my failings in this respect, and I have done this with all the more boldness because Quintilian has said that one can never deviate too much in narrative.It is not necessary in this place to prove whether this be true or not; it is sufficient that Quintilian has made the statement.[5]

I have also considered that, as these fables are already known to all the world, I should have done nothing if I had not rendered them in some degree new, by clothing them with certain fresh characteristics.I have endeavoured to meet the wants of the day, which are novelty and gaiety; and by gaiety I do not mean merely that which excites laughter, but a certain charm, an agreeable air, which may be given to every species of subject, even the most serious.

It is not, however, by the outward form which I have given it that the value of my work should be alone judged, but by the quality of the matter of which it is composed, and by its utility.For what is there that is worthy of praise in the productions of the mind which is not to be found in the apologue?There is something so grand in this species of composition, that many of the ancients have attributed the greater part of these fables to Socrates; selecting as their author that individual amongst mortals who was most directly in communication with the gods.I am rather surprised that they have not maintained that these fables descended direct from heaven,[6] or that they have not attributed their guardianship to some one special deity, as they have done in the case of poetry and eloquence. And what I say is not altogether without foundation, since, if I may venture to speak of that which is most sacred in our eyes in the same breath with the errors of the ancients, we find that Truth has spoken to men in parables; and is the parable anything else than a fable? that is to say, a feigned example of some truth, which has by so much the more force and effect as it is the more common and familiar?

It is for these reasons that Plato, having banished Homer from his Republic, has given a very honourable place in it to Æsop.He maintains that infants suck in fables with their mothers' milk, and recommends nurses to teach them to them, since it is impossible that children should be accustomed at too early an age to the accents of wisdom and virtue.If we would not have to endure the pain of correcting our habits, we should take care to render them good whilst as yet they are neither good nor bad.And what better aids can we have in this work than fables?Tell a child that Crassus, when he waged war against the Parthians, entered their country without considering how he should be able to get out of it again, and that this was the cause of the destruction of himself and his whole army, and how great an effort will the infant have to make to remember the fact! But tell the same child that the fox and the he-goat descended to the bottom of a well for the purpose of quenching their thirst, and that the fox got out of it by making use of the shoulders and horns of his companion as a ladder, but that the goat remained there in consequence of not having had so much foresight, and that, consequently, we should always consider what is likely to be the result of what we do,—tell a child these two stories, I say, and which will make the most impression on his mind? Is it not certain that he will cling to the latter version as more conformable and less disproportioned than the other to the tenderness of his brain? It is useless for you to reply that the ideas of childhood are in themselves sufficiently infantine, without filling them with a heap of fresh trifles. These trifles, as you may please to call them, are only trifles in appearance; in reality, they are full of solid sense. And as by the definition of the point, the line, the surface, and the other well-known elements of form, we obtain a knowledge which enables us to measure not only the earth but the universe, in the same manner, by the aid of the truths involved in fables, we finally become enabled to form correct opinions of what is right and what is wrong, and to take a foremost place in the ranks of life.

The fables which are included in this collection are not merely moral, but are, to a certain extent, an encyclopædia of the qualities and characteristics of animals, and, consequently, of our own; since we men are, in fact, but a summary of all that is good and bad in the lower ranks of creatures.When Prometheus determined upon creating man, he took the dominant characteristic of each beast, and of these various characteristics composed the human species.It follows, therefore, that in these fables, in which beasts play so great a part, we may each of us find some feature which we may recognise as our own.The old may find in them a confirmation of their experiences, and the young may learn from them that which they ought to know.As the latter are but strangers in the world, they are as yet unacquainted with its inhabitants; they are even unacquainted with themselves.They ought not to be left in this ignorance, but should be instructed as to the qualities of the lion, the fox, and so forth, and as to the why and the wherefore a man is sometimes compared to the said lion and fox. To effect this instruction is the object of these fables.

I have already overstepped the ordinary limits of a Preface, but I have still a few remarks to make on the principles on which the present work has been constructed.

The fable proper is composed of two parts, of which one may be termed the body, and the other the soul.The body is the subject-matter of the fable, and the soul is the moral.Aristotle will admit none but animals into the domain of fabledom, and rigorously excludes from it both men and plants.This rule, however, cannot be strictly necessary, since neither Æsop, Phædrus, nor any of the fabulists[7] have observed it; but, on the other hand, a moral is to a fable an indispensable adjunct, and if I have in any instances omitted it, it is only in those cases in which it could not be gracefully introduced, or in which it was so obvious that the reader could deduce it for himself. The great rule in France is to value only that which pleases, and I have thought it no crime, therefore, to cancel ancient customs when they would not harmonise with modern ones. In Æsop's time the fable was first related as a simple story, and then supplemented by a moral which was distinct in itself. Next Phædrus came, who was so far from complying with this rule, that he sometimes transposed the moral from the end to the commencement. For my own part, I have never failed to follow Æsop's rule, except when it was necessary to observe a no less important one laid down by Horace, to the effect that no writer should obstinately struggle against the natural bent of his mind or the capabilities of his subject. A man, he asserts, who wishes to succeed will never pursue such a course, but will at once abandon a subject when he finds that he cannot mould it into a creditable shape:

"Et quæ

Desperat tractata intescere posse, relinquit."[8]

It only remains to speak of the life of Æsop, whose biography by Planudes is almost universally regarded as fabulous. It is supposed that this writer formed the design of attributing a character and adventures to his hero which should bear some resemblance to his fables. This criticism, at first glance, appeared to me sufficiently specious, but I have since found that it has no solid basis. It is partly founded on what took place between Xantus and Æsop, and the quantities of nonsense there contrasted. To which I reply, Who is the sage to whom such things have not happened? The whole of the life even of Socrates was not serious; and what confirms me in my favourable opinion is, that the character which Planudes gives to Æsop is similar to that which Plutarch gives him in his Banquet of the Seven Wise Men—that is, the character of a keen and all-observant man. It may be objected, I know, that the Banquet of the Seven Wise Men is in itself a fiction; and I admit that it is possible to be doubtful about everything. For my own part, I cannot well see why Plutarch should have desired to deceive posterity on this subject, when he has professed to be truthful on every other, and to give to each of his personages his real character. But however this may be, I would ask, Shall I be less likely to be believed if I endorse another man's falsehoods than if I invented some of my own? I might certainly fabricate a tissue of conjectures, and entitle them the "Life of Æsop;" but whatever air of genuineness it might wear, no one could rely upon such a work, and, if he must put up with fiction, the reader would always prefer that of Planudes to mine.

[1] Before the year 1668, when the present collection of fables was first published. Fontaine had already published a few separately, and others had circulated in manuscript.

[2] Patru, a celebrated lawyer, a member of the French Academy, and one of La Fontaine's friends, who made a strange mistake in trying to divert him from a species of composition which has immortalised him.

[3] These fables had long been known when Socrates came into the world, and the Father of Philosophy only took the trouble to render them into verse during the imprisonment which preceded his death.

[4] The word Μουσιχὴ implied amongst the Greeks all the arts to which the Muses devote themselves. It comprises the employments of the mind in opposition to γυμναστιχὴ, which means the exercises of the body. La Fontaine does not give Plato's meaning quite correctly. The philosopher, at the commencement of the "Phædo," makes Socrates say that, having been several times warned in dreams by the gods to study music, he had only regarded it as an encouragement to persevere in the pursuit of truth; but that, since his imprisonment, he had given another interpretation to those warnings, and had decided that he should better obey the wishes of the gods by making verses.

[5] The following is the passage in Quintilian to which the poet alludes:—"Ego vero narrationem, at si ullam partem orationis, omni qua potest gratia et venere exorundam." —Quint., "Hist Orat." lib.ix., cap iv.

[6] La Fontaine has not ventured altogether to repair the oversight of the ancients, for he has left the origin of fables a doubtful point between heaven and earth, when he says, in a dedication to Madame de Montespan, "The fable is a gift which comes from the immortals; if it were the gift of man, he who gave it us would indeed deserve a temple."

[7] The word fabulist was invented by La Fontaine, and has no equivalent either in the Greek or Latin languages. La Motte only ventured to use it under cover of the authority of our poet; and the French Academy, having declined to admit it into the first edition of its Dictionary, which was published after La Fontaine's death, only did so when it had been sanctioned by usage and public admiration.

[8] Hor., "Ars Poet.," v.150.

TO

MONSEIGNEUR THE DAUPHIN.

I sing the heroes who call Æsop father,

Whose history, although deceitful rather,

Some truths and useful lessons, too, contains.

Everything finds a tongue in these my strains;

And what they say is wholesome: now and then

My animals I use as texts for men.

Illustrious branch of one the gods hold dear,

And by the whole world held in love and fear,

He who the proudest chiefs at once defies,

And counts the days by glorious victories,

Others will better tell, and higher soar,

To sing your mighty ancestors of yore;

But I would please thee in a humbler way,

And trace in verse the sketches I essay;

Yet if to please thee I do not succeed,

At least the fame of trying be my meed.

THE GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANT.

FABLE I.

THE GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANT.

The Grasshopper, so blithe and gay,

Sang the summer time away.

Pinched and poor the spendthrift grew,

When the sour north-easter blew.

In her larder not a scrap,

Bread to taste, nor drink to lap.

To the Ant, her neighbour, she

Went to moan her penury,

Praying for a loan of wheat,

Just to make a loaf to eat,

Till the sunshine came again.

"All I say is fair and plain,

I will pay you every grain,

Principal and interest too,

Before harvest, I tell you,

On my honour—every pound,

Ere a single sheaf is bound."

The Ant's a very prudent friend,

Never much disposed to lend;

Virtues great and failings small,

This her failing least of all.

Quoth she, "How spent you the summer?"

"Night and day, to each new comer

I sang gaily, by your leave;

Singing, singing, morn and eve."

"You sang? I see it at a glance.

Well, then, now's the time to dance."

FABLE II.

THE RAVEN AND THE FOX.

Master Raven, perched upon a tree,

Held in his beak a savoury piece of cheese;

Its pleasant odour, borne upon the breeze,

Allured Sir Reynard, with his flattery.

"Ha! Master Raven, 'morrow to you, sir;

How black and glossy! now, upon my word,

I never—beautiful! I do aver.

If but your voice becomes your coat, no bird

More fit to be the Phœnix of our wood—

I hope, sir, I am understood?"

The Raven, flattered by the praise,

Opened his spacious beak, to show his ways

Of singing: down the good cheese fell.

Quick the Fox snapped it. "My dear sir, 'tis well,"

He said. "Know that a flatterer lives

On him to whom his praise he gives;

And, my dear neighbour, an' you please,

This lesson's worth a slice of cheese." —

The Raven, vexed at his consenting,

Flew off, too late in his repenting.

FABLE III.

THE FROG THAT WISHED TO MAKE HERSELF AS BIG AS THE OX.

A Frog, no bigger than a pullet's egg,

A fat Ox feeding in a meadow spied.

The envious little creature blew and swelled;

In vain to reach the big bull's bulk she tried.

"Sister, now look! observe me close!" she cried.

"Is this enough?" —"No!" "Tell me! now then see!"

"No, no!" "Well, now I'm quite as big as he?"

"You're scarcely bigger than you were at first!"

One more tremendous puff—she grew so large—she burst.

The whole world swarms with people not more wise:

The tradesman's villa with the palace vies.

Ambassadors your poorest Princelings send,

And every Count has pages without end.

THE TWO MULES.

FABLE IV.

THE TWO MULES.

Two Mules were journeying—one charged with oats,

The other with a tax's golden fruit.

This last betrayed that manner which denotes

Excessive vanity in man or brute.

Proudly self-conscious of his precious load,

He paced, and loud his harness-bells resounded;

When suddenly upon their lonely road,

Both Mules and masters were by thieves surrounded.

The money-bearer soon was put to death:

"Is this the end that crowns my high career?

Yon drudge," he murmured with his latest breath,

"Escapes unhurt, while I must perish here!"

"My friend," his fellow-traveller made reply,

"Wealth cannot always at the poor man scoff.

If you had been content to do as I,

You'd not at present be so badly off."

FABLE V.

THE WOLF AND THE DOG.

A Wolf, who was but skin and bone,

So watchful had the sheep-dogs grown,

Once met a Mastiff fat and sleek,

Stern only to the poor and weak.

Sir Wolf would fain, no doubt, have munched

This pampered cur, and on him lunched;

But then the meal involved a fight,

And he was craven, save at night;

For such a dog could guard his throat

As well as any dog of note.

So the Wolf, humbly flattering him,

Praised the soft plumpness of each limb.

"You're wrong, you're wrong, my noble sir,

To roam in woods indeed you err,"

The dog replies, "you do indeed;

If you but wish, with me you'll feed.

Your comrades are a shabby pack,

Gaunt, bony, lean in side and back,

Pining for hunger, scurvy, hollow,

Fighting for every scrap they swallow.

Come, share my lot, and take your ease."

"What must I do to earn it, please?"

"Do? —why, do nothing! Beggar-men

Bark at and chase; fawn now and then

At friends; your master always flatter.

Do this, and by this little matter

Earn every sort of dainty dish—

Fowl-bones or pigeons'—what you wish—

Aye, better things; and with these messes,

Fondlings, and ceaseless kind caresses."

The Wolf, delighted, as he hears

Is deeply moved—almost to tears;

When all at once he sees a speck,

A gall upon the Mastiff's neck.

"What's that?" —"Oh, nothing!" "Nothing?" —"No!"

"A slight rub from the chain, you know."

"The chain!" replies the Wolf, aghast;

"You are not free? —they tie you fast?"

"Sometimes. But, law! what matters it?" —

"Matters so much, the rarest bit

Seems worthless, bought at such a price."

The Wolf, so saying, in a trice,

Ran off, and with the best goodwill,

And very likely's running still.

FABLE VI.

THE HEIFER, THE SHE-GOAT, AND THE LAMB, IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE LION.

The Heifer, Lamb, and Nanny-goat were neighbours,

With a huge Lion living close at hand,

They shared the gains and losses of their labours

(All this was long ago, you understand).

One day a stag was taken as their sport;

The Goat, who snared him, was of course enraptured,

And sent for all the partners of her toil,

In order to divide the treasure captured.

They came. The Lion, counting on his claws,

Quartered the prey, and thus addressed the trio—

"The parts are four. I take the first, because

I am your monarch, and my name is Leo:

Being the strongest, I annex the second;

As bravest, I can claim another share,

Should any touch the fourth, or say I reckoned

Unjustly, I shall kill him.So beware."

FABLE VII.

THE WALLET.

Said Jupiter one day, "Let all that breathe

Come and obeisance make before my throne.

If at his shape or being any grieve,

Let them cast fears aside. I'll hear their groan.

Come, Monkey, you be first to speak. You see

Of animals this goodly company;

Compare their beauties with your own.

Are you content?" "Why not? Good gracious me!"

The monkey said,

No whit afraid—

"Why not content? I have four feet like others,

My portrait no one sneers at—do they, brothers?

But cousin Bruins hurriedly sketched in,

And no one holds his likeness worth a pin."

Then came the Bear. One thought he would have found

Something to grumble at. Grumble! no, not he.

He praised his form and shape, but, looking round,

Turned critic on the want of symmetry

Of the huge shapeless Elephant, whose ears

Were much too long; his tail too short, he fears.

The Elephant was next.

Though wise, yet sadly vexed

To see good Madam Whale, to his surprise,

A cumbrous mountain of such hideous size.

Quick Mrs. Ant thinks the Gnat far too small,

Herself colossal. —Jove dismisses all,

Severe on others, with themselves content.

'Mong all the fools who that day homeward went,

Our race was far the worst: our wisest souls

Lynxes to others', to their own faults moles.

Pardon at home they give, to others grace deny,

And keep on neighbours' sins a sleepless eye.

Jove made us so,

As we all know,

We wear our Wallets in the self-same way—

This current year, as in the bye-gone day:

In pouch behind our own defects we store,

The faults of others in the one before.

FABLE VIII.

THE SWALLOW AND THE LITTLE BIRDS.

A Swallow, in his travels o'er the earth,

Into the law of storms had gained a peep;

Could prophesy them long before their birth,

And warn in time the ploughmen of the deep.

Just as the month for sowing hemp came round,

The Swallow called the smaller birds together.

"Yon' hand," said he, "which strews along the ground

That fatal grain, forbodes no friendly weather.

The day will come, and very soon, perhaps,

When yonder crop will help in your undoing—

THE SWALLOW AND THE LITTLE BIRDS.

When, in the shape of snares and cruel traps,

Will burst the tempest which to-day is brewing.

Be wise, and eat the hemp up now or never;

Take my advice."But no, the little birds,

Who thought themselves, no doubt, immensely clever,

Laughed loudly at the Swallow's warning words.

Soon after, when the hemp grew green and tall,

He begged the Birds to tear it into tatters.

"Prophet of ill," they answered one and all,

"Cease chattering about such paltry matters."

The hemp at length was ripe, and then the Swallow,

Remarking that "ill weeds were never slow,"

Continued—"Though it's now too late to follow

The good advice I gave you long ago,

You still may manage to preserve your lives

By giving credit to the voice of reason.

Remain at home, I beg you, with your wives,

And shun the perils of the coming season.

You cannot cross the desert or the seas,

To settle down in distant habitations;

Make nests, then, in the walls, and there, at ease,

Defy mankind and all its machinations."

They scorned his warnings, as in Troy of old

Men scorned the lessons that Cassandra taught.

And shortly, as the Swallow had foretold,

Great numbers of them in the traps were caught.

To instincts not our own we give no credit,

And till misfortune comes, we never dread it.

THE TOWN RAT AND THE COUNTRY RAT.

FABLE IX.

THE TOWN RAT AND THE COUNTRY RAT.

A Rat from town, a country Rat

Invited in the civilest way;

For dinner there was just to be

Ortolans and an entremet.

Upon a Turkey carpet soft

The noble feast at last was spread;

I leave you pretty well to guess

The merry, pleasant life they led.

Gay the repast, for plenty reigned,

Nothing was wanting to the fare;

But hardly had it well begun

Ere chance disturbed the friendly pair.

A sudden racket at the door

Alarmed them, and they made retreat;

The City Rat was not the last,

His comrade followed fast and fleet.

The noise soon over, they returned,

As rats on such occasions do;

"Come," said the liberal citizen,

"And let us finish our ragout."

"Not a crumb more," the rustic said;

"To-morrow you shall dine with me;

Don't think me jealous of your state,

Or all your royal luxury;

"But then I eat so quiet at home,

And nothing dangerous is near;

Good-bye, my friend, I have no love

For pleasure when it's mixed with fear."

FABLE X.

THE MAN AND HIS IMAGE.

FOR M.THE DUKE DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULD.

A man who had no rivals in the love

He bore himself, thought that he won the bell

From all the world, and hated every glass

That truths less palatable tried to tell.

Living contented in the error,

Of lying mirrors he'd a terror.

Officious Fate, determined on a cure,

Raised up, where'er he turned his eyes,

Those silent counsellors that ladies prize.

Mirrors old and mirrors newer;

Mirrors in inns and mirrors in shops;

Mirrors in pockets of all the fops;

Mirrors in every lady's zone.

What could our poor Narcissus do?

He goes and hides him all alone

In woods that one can scarce get through.

No more the lying mirrors come,

But past his new-found savage home

A pure and limpid brook runs fair. —

He looks. His ancient foe is there!

His angry eyes stare at the stream,

He tries to fancy it a dream.

Resolves to fly the odious place, and shun

The image; yet, so fair the brook, he cannot run.

My meaning is not hard to see;

No one is from this failing free.

The man who loved himself is just the Soul,

The mirrors are the follies of all others.

(Mirrors are faithful painters on the whole;)

And you know well as I do, brothers, that the brook

Is the wise "Maxim-book."[1]

[1] Rochefoucauld's Maxims are the most extraordinary dissections of human selfishness ever made.

FABLE XI.

THE DRAGON WITH MANY HEADS, AND THE DRAGON WITH MANY TAILS.

An Envoy of the Grand Signor

(I can't say more)

One day, before the Emperor's court,

Vaunted, as some historians report,

That his royal master had a force

Outnumbering all the foot and horse

The Kaiser could bring to the war.

Then spoke a choleric attendant:

"Our Prince has more than one dependant

That keeps an army at his own expense."

The Pasha (man of sense),

Replied: "By rumour I'm aware

What troops the great electors spare,

And that reminds me, I am glad,

Of an adventure I once had,

Strange, and yet true.

I'll tell it you.

Once through a hedge the hundred heads I saw

Of a huge Hydra show.

My blood, turned ice, refused to flow:

And yet I felt that neither fang nor claw

Could more than scare me—for no head came near.

There was no room. I cast off fear.

While musing on this sight,

Another Dragon came to light.

Only one head this time;

But tails too many to count up in rhyme.

The fit again came on,

Worse than the one just gone.

The head creeps first, then follows tail by tail;

Nothing can stop their road, nor yet assail;

One clears the way for all the minor powers:

The first's your Emperor's host, the second ours."

THE WOLF AND THE LAMB.

FABLE XII.

THE WOLF AND THE LAMB.

The reasoning of the strongest has such weight,

None can gainsay it, or dare prate,

No more than one would question Fate.

A Lamb her thirst was very calmly slaking,

At the pure current of a woodland rill;

A grisly Wolf, by hunger urged, came making

A tour in search of living things to kill.

"How dare you spoil my drink?" he fiercely cried;

There was grim fury in his very tone;

"I'll teach you to let beasts like me alone.

"Let not your Majesty feel wrath," replied

The Lamb, "nor be unjust to me, from passion;

I cannot, Sire, disturb in any fashion

The stream which now your Royal Highness faces,

I'm lower down by at least twenty paces."

"You spoil it!" roared the Wolf; "and more, I know,

You slandered me but half a year ago."

"How could I do so, when I scarce was born?"

The Lamb replied; "I was a suckling then."

"Then 'twas your brother held me up to scorn."

"I have no brother." "Well, 'tis all the same;

At least 'twas some poor fool that bears your name.

You and your dogs, both great and small,

Your sheep and shepherds, one and all,

Slander me, if men say but true,

And I'll revenge myself on you."

Thus saying, he bore off the Lamb

Deep in the wood, far from its dam.

And there, not waiting judge nor jury,

Fell to, and ate him in his fury.

FABLE XIII.

THE ROBBERS AND THE ASS.

Two Thieves were fighting for a prize,

A Donkey newly stolen; sell or not to sell—

That was the question—bloody fists, black eyes:

While they fought gallantly and well,

A third thief happening to pass,

Rode gaily off upon the ass.

The ass is some poor province it may be;

The thieves, that gracious potentate, or this,

Austria, Turkey, or say Hungary;

Instead of two, I vow I've set down three

(The world has almost had enough of this),

And often neither will the province win:

For third thief stepping in,

'Mid their debate and noisy fray,

With the disputed donkey rides away.

THE ROBBERS AND THE ASS.

FABLE XIV.

DEATH AND THE WOODCUTTER.

A poor Woodcutter, covered with his load,

Bent down with boughs and with a weary age,

Groaning and stooping, made his sorrowing stage

To reach his smoky cabin; on the road,

Worn out with toil and pain, he seeks relief

By resting for a while, to brood on grief. —

What pleasure has he had since he was born?

In this round world is there one more forlorn?

Sometimes no bread, and never, never rest.

Creditors, soldiers, taxes, children, wife,

The corvée.Such a life!

The picture of a miserable man—look east or west.

He calls on Death—for Death calls everywhere—

Well,—Death is there.

He comes without delay,

And asks the groaner if he needs his aid.

"Yes," said the Woodman, "help me in my trade.

Put up these faggots—then you need not stay."

Death is a cure for all, say I,

But do not budge from where you are;

Better to suffer than to die,

Is man's old motto, near and far.

DEATH AND THE WOODCUTTER.

FABLE XV.

SIMONIDES RESCUED BY THE GODS.

Three sorts of persons can't he praised too much:

The Gods, the King, and her on whom we doat.

So said Malherbe, and well he said, for such

Are maxims wise, and worthy of all note.

Praise is beguiling, and disliked by none:

A lady's favour it has often won.

Let's see whate'en the gods have ere this done

To those who praised them.Once, the eulogy

Of a rough athlete was in verse essayed.

Simonides, the ice well broken, made

A plunge into a swamp of flattery.

The athlete's parents were poor folk unknown;

The man mere lump of muscle and of bone—

No merit but his thews,

A barren subject for the muse.

The poet praised his hero all he could,

Then threw him by, as others would.

Castor and Pollux bringing on the stage,

He points out their example to such men,

And to all strugglers in whatever age;

Enumerates the places where they fought,

And why they vanished from our mortal ken.

In fact, two-thirds of all his song was fraught

With praise of them, page after page.

A Talent had the athlete guaranteed,

But when he read he grudged the meed,

And gave a third: frank was his jest,—

"Castor and Pollux pay the rest;

Celestial pair! they'll see you righted,—

Still I will feast you with the best;

Sup with me, you will be delighted;

The guests are all select, you'll see,

My parents, and friends loved by me;

Be thou, too, of the company."

Simonides consents, partly, perhaps, in fear

To lose, besides his due, the paltry praise.

He goes—they revel and discuss the cheer;

A merry night prepares for jovial days.

A servant enters, tells him at the door

Two men would see him, and without delay.

He leaves the table, not a bit the more

Do jaws and fingers cease their greedy play.

These two men were the Gemini he'd praised.

They thanked him for the homage he had paid;

Then, for reward, told him the while he stayed

The doom'd house would be rased,

And fall about the ears

Of the big boxer and his peers.

The prophecy came true—yes, every tittle;

Snap goes a pillar, thin and brittle.

The roof comes toppling down, and crashes

The feast—the cups, the flagons smashes.

Cupbearers are included in the fall;

Nor is that all:

To make the vengeance for the bard complete,

The athlete's legs are broken too.

A beam snapped underneath his feet,

While half the guests exclaim,

"Lord help us!we are lame."

Fame, with her trumpet, heralds the affair;

Men cry, "A miracle!" and everywhere

They give twice over, without scoff or sneer,

To poet by the gods held dear.

No one of gentle birth but paid him well,

Of their ancestors' deeds to nobly tell.

Let me return unto my text: it pays

The gods and kings to freely praise;

Melpomene, moreover, sometimes traffic makes

Of the ingenious trouble that she takes.

Our art deserves respect, and thus

The great do honour to themselves who honour us.

Olympus and Parnassus once, you see,

Were friends, and liked each other's company.

FABLE XVI.

DEATH AND THE UNHAPPY MAN.

A Miserable Man incessant prayed

To Death for aid.

"Oh, Death!" he cried. "I love thee as a friend!

Come quickly, and my life's long sorrows end!"

Death, wishing to oblige him, ran,

Knocked at the door, entered, and eyed the man.

"What do I see? begone, thou hideous thing!

The very sight

Strikes me with horror and affright!

Begone, old Death! —Away, thou grisly King!"

Mecænas (hearty fellow) somewhere said;

"Let me be gouty, crippled, impotent and lame,

'Tis all the same.

So I but keep on living. Death, thou slave!

Come not at all, and I shall be content."

And that was what the man I mention meant.

THE WOLF TURNED SHEPHERD.

FABLE XVII.

THE WOLF TURNED SHEPHERD.

A Wolf who found in cautious flocks

His tithes beginning to be few,

Thought that he'd play the part of Fox,

A character at least quite new.

A Shepherd's hat and coat he took,

And from a branch he made a hook;

Nor did the pastoral pipe forget.

To carry out his schemes he set,

He would have liked to write upon his hat,

"I'm Guillot, Shepherd of these sheep!"

And thus disguised, he came, pit-pat,

And softly stole where fast asleep

Guillot himself lay by a stack,

His dog close cuddling at his back;

His pipe too slept; and half the number

Of the plump sheep was wrapped in slumber.

He's got the dress—could he but mock

The Shepherd's voice, he'd lure the flock:

He thought he could.

That spoiled the whole affair—he'd spoken;

His howl re-echoed through the wood.

The game was up—the spell was broken!

They all awake, dog, Shepherd, sheep.

Poor Wolf, in this distress

And pretty mess,

In clumsy coat bedight,

Could neither run away nor fight.

At last the bubble breaks;

There's always some mistake a rascal makes.

The Wolf like Wolf must always act;

That is a very certain fact.

FABLE XVIII.

THE CHILD AND THE SCHOOLMASTER.

This fable serves to tell, or tries to show

A fools remonstrance often is in vain.

A child fell headlong in the river's flow,

While playing on the green banks of the Seine:

A willow, by kind Providence, grew there,

The branches saved him (rather, God's good care);

Caught in the friendly boughs, he clutched and clung.

The master of the school just then came by.

"Help! help! I'm drowning!" as he gulping hung,

He shouts.The master, with a pompous eye,

Turns and reproves him with much gravity.

"You little ape," he said, "now only see

What comes of all your precious foolery;

A pretty job such little rogues to guard.

Unlucky parents who must watch and thrash.

Such helpless, hopeless, good-for-nothing trash.

I pity them; their woes I understand."

Having said this, he brought the child to land.

In this I blame more people than you guess—

Babblers and censors, pedants, all the three;

Such creatures grow in numbers to excess,

Some blessing seems to swell their progeny.

In every crisis theories they shape,

And exercise their tongues with perfect skill;

Ha! my good friends, first save me from the scrape,

Then make your long speech after, if you will.

FABLE XIX.

THE PULLET AND THE PEARL.

A Fowl, while scratching in the straw,

Finding a pearl without a flaw,

Gave it a lapidary of the day.

"It's very fine, I must repeat;

And yet a single grain of wheat

Is very much more in my way."

A poor uneducated lad

A manuscript as heirloom had.

He took it to a bookseller one day:

"I know," said he, "it's very rare;

But still, a guinea as my share

Is very much more in my way."

FABLE XX.

THE DRONES AND THE BEES.

A Workman by his work you always know.

Some cells of honey had been left unclaimed.

The Drones were first to go

The Bees, to try and show

That they to take the mastership were not ashamed.

Before a Wasp the cause at last they bring;

It is not easy to decide the thing.

The witnesses deposed that round the hive

They long had seen wing'd, buzzing creatures fly,

Brown, and like bees. "Yes, true; but, man alive,

The Drones are also brown; so do not try

To prove it so."The Wasp, on justice bent,

Made new investigations

(Laws of all nations).

To throw more light upon the case,

Searched every place,

Heard a whole ants' nest argue face to face,

Still it grew only darker; that's a fact

(Lease or contract?)

"Oh, goodness gracious! where's the use, my son?"

Cried a wise Bee;

"Why, only see,

For six months now the cause is dragging on,

And we're no further than we were at first;

But what is worst,

The honey's spoiling, and the hive is burst.

'Tis time the judge made haste,

The matter's simmered long enough to waste,

Without rebutters or fi, fa,

Without rejoinders or ca, sa,

John Doe,

Or Richard Roe.

Let's go to work, the wasps and us,

We'll see who best can build and store

The sweetest juice."It's settled thus.

The Drones do badly, as they've done of yore;

The art's beyond their knowledge, quite beyond.

The Wasp adjudges that the honey goes

Unto the Bees: would those of law so fond

Could thus decide the cases justice tries.

Good common sense, instead of Coke and code,

(The Turks in this are really very wise,)

Would save how many a debtor's heavy load.

Law grinds our lives away

With sorrow and delay.

In vain we groan, and grudge

The money given to our long-gowned tutors.

Always at last the oyster's for the judge,

The shells for the poor suitors.

THE OAK AND THE REED.

FABLE XXI.

THE OAK AND THE REED.

The Oak said one day to a river Reed,

"You have a right with Nature to fall out.

Even a wren for you's a weight indeed;

The slightest breeze that wanders round about

Makes you first bow, then bend;

While my proud forehead, like an Alp, braves all,

Whether the sunshine or the tempest fall—

A gale to you to me a zephyr is.

Come near my shelter: you'll escape from this;

You'll suffer less, and everything will mend.

I'll keep you warm

From every storm;

And yet you foolish creatures needs must go,

And on the frontiers of old Boreas grow.

Nature to you has been, I think, unjust."

"Your sympathy," replied the Reed, "is kind,

And to my mind

Your heart is good; and yet dismiss your thought.

For us, no more than you, the winds are fraught

With danger, for I bend, but do not break.

As yet, a stout resistance you can make,

And never stoop your back, my friend;

But wait a bit, and let us see the end."

Black, furious, raging, swelling as he spoke,

The fiercest wind that ever yet had broke

From the North's caverns bellowed through the sky.

The Oak held firm, the Reed bent quietly down.

The wind blew faster, and more furiously,

Then rooted up the tree that with its head

Had touched the high clouds in its majesty,

And stretched far downwards to the realms of dead.

FABLE XXII.

AGAINST THOSE WHO ARE HARD TO PLEASE.

Had I when born, from fair Calliope

Received a gift such as she can bestow

Upon her lovers, it should pass from me

To Æsop, and that very soon, I know;

I'd consecrate it to his pleasant lies.

Falsehood and verse have ever been allies;

Far from Parnassus, held in small esteem,

I can do little to adorn his theme,

Or lend a fresher lustre to his song.

I try, that's all—and plan what one more strong

May some day do—

And carry through.

Still, I have written, by-the-bye,

The wolf's speech and the lamb's reply.

What's more, there's many a plant and tree

Were taught to talk, and all by me.

Was that not my enchantment, eh?

"Tut! Tut!" our peevish critics say,

"Your mighty work all told, no more is

Than half-a-dozen baby stories.

Write something more authentic then,

And in a higher tone." —Well, list, my men! —

After ten years of war around their towers,

The Trojans held at bay the Grecian powers;

A thousand battles on Scamander's plain,

Minings, assaults, how many a hero slain!

Yet the proud city stoutly held her own.

Till, by Minerva's aid, a horse of wood,

Before the gates of the brave city stood.

Its flanks immense the sage Ulysses hold,

Brave Diomed, and Ajax, churlish, bold;

These, with their squadrons, will the vast machine

Bear into fated Troy, unheard, unseen—

The very gods will be their helpless prey.

Unheard-of stratagem; alas! the day,

That will the workmen their long toil repay. —

"Enough, enough!" our critics quickly cry,

"Pause and take breath; you'll want it presently.

Your wooden horse is hard to swallow,

With foot and cavalry to follow.

Why this is stranger stuff, now, an' you please,

Than Reynard cheating ravens of their cheese;

What's more, this grand style does not suit you well,

That way you'll never bear away the bell."

Well, then, we'll lower the key, if such your will is. —

Pensive, alone, the jealous Amaryllis

Sighed for Alcippus—in her care,

She thinks her sheep and dog alone will share.

Tircis, perceiving her, slips all unseen

Behind the willows' waving screen,

And hears the shepherdess the zephyrs pray,

To bear her words to lover far away. —

"I stop you at that rhyme,"

Cries out my watchful critic,

Of phrases analytic;

"It's not legitimate; it cannot pass this time.

And then I need not show, of course,

The line wants energy and force;

It must be melted o'er again, I say."

You paltry meddler, prate no more,

I write my stories at my ease.

Easier to sit and plan a score,

Than such a one as you to please.

Fastidious men and overwise,

There's nothing ever satisfies.

THE COUNCIL HELD BY THE RATS.

FABLE XXIII.

THE COUNCIL HELD BY THE RATS.

A Tyrant Cat, by surname Nibblelard,

Through a Rat kingdom spread such gloom

By waging war and eating hard,

Only a few escaped the tomb;

The rest, remaining in their hiding-places,

Like frightened misers crouching on their pelf,

Over their scanty rations made wry faces,

And swore the Cat was old King Nick himself.

One day, the terror of their life

Went on the roof to meet his wife:

During the squabbling interview

(I tell the simple truth to you),

The Rats a chapter called. The Dean,

A cautious, wise, old Rat,

Proposed a bell to fasten on the Cat.

"This should be tried, and very soon, I mean;

So that when war was once begun,

Safe underground their folk could run,—

This was the only thing that could be done."

With the wise Dean no one could disagree;

Nothing more prudent there could be:

The difficulty was to fix the bell!

One said, "I'm not a fool; you don't catch me:"

"I hardly seem to see it!" so said others.

The meeting separated—need I tell,

The end was words—but words. Well, well, my brothers,

There have been many chapters much the same;

Talking, but never doing—there's the blame.

Chapters of monks, not rats—just so!

Canons who fain would bell the cats, you know.

To talk, and argue, and refute,

The court has lawyers in long muster-roll;

But when you want a man who'll execute,

You cannot find a single soul.

FABLE XXIV.

THE WOLF PLEADING AGAINST THE FOX BEFORE THE APE.

A Wolf who'd suffered from a thief,

His ill-conditioned neighbour Mr. Fox

Brought up (and falsely, that is my belief)

Before the Ape, to fill the prisoner's box.

The plaintiff and defendant in this case

Distract the place

With questions, answers, cries, and boisterous speeches,

So angry each is.

In an Ape's memory no one saw

An action so entangled as to law.

Hot and perspiring was the judge's face,

He saw their malice, and, with gravity,

Decided thus:—"I know you well of old, my friends,

Both must pay damages, I see;

You, Wolf, because you've brought a groundless charge:

You, Fox, because you stole from him; on that I'll not enlarge."

The judge was right; it's no bad plan,

To punish rascals how you can.

FABLE XXV.

THE MIDDLE-AGED MAN AND THE TWO WIDOWS.

A Man of middle age,

Fast getting grey,

Thought it would be but sage

To fix the marriage day.

He had in stocks,

And under locks,

Money enough to clear his way.

Such folks can pick and choose; all tried to please

The moneyed man; but he, quite at his ease,

Showed no great hurry,

Fuss, nor scurry.

"Courting," he said, "was no child's play."

Two widows in his heart had shares—

One young; the other, rather past her prime,

By careful art repairs

What has been carried off by Time.

The merry widows did their best

To flirt and coax, and laugh and jest;

Arranged, with much of bantering glee,

His hair, and curled it playfully.

The eldest, with a wily theft,

Plucked one by one the dark hairs left.

The younger, also plundering in her sport,

Snipped out the grey hair, every bit.

Both worked so hard at either sort,

They left him bald—that was the end of it.

"A thousand thanks, fair ladies," said the man;

"You've plucked me smooth enough;

Yet more of gain than loss, so quantum suff.,

For marriage now is not at all my plan.

She whom I would have taken t'other day

To enroll in Hymen's ranks,

Had but the wish to make me go her way,

And not my own;

A head that's bald must live alone:

For this good lesson, ladies, many thanks."

FABLE XXVI.

THE FOX AND THE STORK.

The Fox invited neighbour Stork to dinner,

But Reynard was a miser, I'm afraid;

He offered only soup, and that was thinner

Than any soup that ever yet was made.

The guest—whose lanky beak was an obstruction,

The mixture being served upon a plate—

Made countless vain experiments in suction,

While Reynard feasted at a rapid rate.

The victim, bent upon retaliation,

Got up a little dinner in return.

Reynard accepted; for an invitation

To eat and drink was not a thing to spurn.

He reached the Stork's at the appointed hour,

Flattered the host, as well as he was able,

And got his grinders ready to devour

Whatever dishes might be brought to table.

But, lo! the Stork, to punish the offender,

Had got the meat cut very fine, and placed

Within a jug; the neck was long and slender,

Suited exactly to its owner's taste.

The Stork, whose appetite was most extensive,

Emptied the jug entirely to the dregs;

While hungry Reynard, quite abashed and pensive,

Walked homewards with his tail between his legs.

Deceivers reap the fruits of their deceit,

And being cheated may reform a cheat.

THE LION AND THE GNAT.

FABLE XXVII.

THE LION AND THE GNAT.

"Go, paltry insect, refuse of the earth!"

Thus said the Lion to the Gnat one day.

The Gnat held the Beast King as little worth;

Immediate war declared—no joke, I say.

"Think you I care for Royal name?

I care no button for your fame;

An ox is stronger far than you,

Yet oxen often I pursue."

This said; in anger, fretful, fast,

He blew his loudest trumpet blast,

And charged upon the Royal Nero,

Himself a trumpet and a hero.

The time for vengeance came;

The Gnat was not to blame.

Upon the Lion's neck he settled, glad

To make the Lion raving mad;

The monarch foams: his flashing eye

Rolls wild. Before his roaring fly

All lesser creatures; close they hide

To shun his cruelty and pride:

And all this terror at

The bite of one small Gnat,

Who changes every moment his attack,

First on the mouth, next on the back;

Then in the very caverns of the nose,

Gives no repose.

The foe invisible laughed out,

To see a Lion put to rout;

Yet clearly saw

That tooth nor claw

Could blood from such a pigmy draw.

The helpless Lion tore his hide,

And lashed with furious tail his side;

Lastly, quite worn, and almost spent,

Gave up his furious intent.

With glory crowned, the Gnat the battle-ground

Leaves, his victorious trump to sound,

As he had blown the battle charge before,

Still one blast for the conquest more.

He flies now here, now there,

To tell it everywhere.

Alas! it so fell out he met

A spider's ambuscaded net,

And perished, eaten in mid-air.

What may we learn by this? why, two things, then:

First, that, of enemies, the smaller men

Should most be dreaded; also, secondly,

That passing through great dangers there may be

Still pitfalls waiting for us, though too small to see.

FABLE XXVIII.

THE ASS LADEN WITH SPONGES, AND THE ASS LADEN WITH SALT.

A Peasant, like a Roman Emperor bearing

His sceptre on his shoulder, proudly

Drove his two steeds with long cars, swearing

At one of them, full often and full loudly.

The first, with sponges laden, fast and fleet

Moved well its feet:

The second (it was hardly its own fault)

Bore bags of salt.

O'er mountain, dale, and weary road.

The weary pilgrims bore their load,

Till to a ford they came one day;

They halted there

With wondering air;

The driver knowing very well the way,

Leaped on the Ass the sponges' load that bore,

And drove the other beast before.

That Ass in great dismay

Fell headlong in a hole;

Then plashed and scrambled till he felt

The lessening salt begin to melt;

His shoulders soon had liberty,

And from their heavy load were free.

His comrade takes example from his brother,

As sheep will follow one another;

Up to his neck the creature plunges

Himself, his rider, and the sponges;

All three drank deep, the man and Ass

Tipple together many a glass.

The load seemed turned to lead;

The Ass, now all but dead,

Quite failed to gain the bank: his breath

Was gone: the driver clung like death

Till some one came, no matter who, and aid.

Enough, if I have shown by what I've said,

That all can't act alike, you know;

And this is what I wished to show.

FABLE XXIX.

THE LION AND THE RAT.

It's well to please all people when you can;

There's none so small but one his aid may need.

Here are two fables, if you give good heed,

Will prove the truth to any honest man.

A Rat, in quite a foolish way,

Crept from his hole between a Lion's paws;

The king of animals showed on that day

His royalty, and never snapped his jaws.

The kindness was not unrepaid;

Yet, who'd have thought a Lion would need aid

THE LION AND THE RAT.

From a poor Rat?

Soon after that

The Lion in the forest brake,

In their strong toils the hunters take;

In vain his roars, his frenzy, and his rage.

But Mr. Rat runs up; a mesh or two

Nibbles, and lets the Lion through

Patience and length of time may sever,

What strength and empty wrath could never.

FABLE XXX.

THE DOVE AND THE ANT.

The next example we must get

From creatures even smaller yet.

A Dove came to a brook to drink,

When, leaning on the crumbling brink,

An Ant fell in, and failed to reach,

Through those vast ocean waves, the beach.

The Dove, so full of charity is she,

Threw down a blade of grass, a promontory,

Unto the Ant, who so once more,

Grateful and glad, escaped to shore.

Just then passed by

A scampish poacher, soft, bare-footed, came

Creeping and sly;

A crossbow in his hand he bore:

Seeing the Dove, he thought the game

Safe in the pot, and ready for the meal:

Quick runs the Ant, and stings his heel;

The angry rascal turns his head;

The Dove, who sees the scoundrel stoop,

Flies off, and with her flies his soup.

FABLE XXXI.

THE ASTROLOGER WHO LET HIMSELF FALL INTO THE WELL.

To an Astrologer, who by a blunder

Fell in a well, said one, "You addle-head,

Blind half an inch before your nose, I wonder

How you can read the planets overhead."

This small adventure, not to go beyond,

A useful lesson to most men may be;

How few there are at times who are not fond

Of giving reins to their credulity,

Holding that men can read,

In times of need,

The solemn Book of Destiny,

That book, of which old Homer sung,

What was the ancient chance, in common sense,

but modern Providence?

Chance that has always bid defiance

To laws and schemes of human science.

If it were otherwise, a single glance

Would tell us there could be no fortune and no chance.

All things uncertain;

Who can lift the curtain?

Who knows the will of the Supreme?

He who made all, and all with a design;

Who but himself can know them?who can dream

He reads the thoughts of the Divine,

Did God imprint upon the star or cloud

The secrets that the night of Time enshroud,

In darkness hid? —only to rack the brains

Of those who write on what each sphere contains.

To help us shun inevitable woes,

And sadden pleasure long before its close;

Teaching us prematurely to destroy,

And turn to evil every coming joy,

This is an error, nay, it is a crime.

The firmament rolls on, the stars have destined time.

The sun gives light by day,

And drives the shadows of the night away.

Yet what can we deduce but that the will Divine

Bids them rise and bids them shine,

To lure the seasons on, to ripen every seed,

To shed soft influence on men;

What has an ordered universe to do indeed,

With chance, that is beyond our ken.

Horoscope-makers, cheats, and quacks.

On Europe's princes turn your backs,

And carry with you every bellows-working alchymist:

You are as bad as they, I wist. —

But I am wandering greatly, as I think,

Let's turn to him whom Fate forced deep to drink.

Besides the vanity of his deceitful art,

He is the type of those who at chimeras gape,

Forgetting danger's simpler shape,

And troubles that before us and behind us start.

THE HARE AND THE FROGS.

FABLE XXXII.

THE HARE AND THE FROGS.

One day sat dreaming in his form a Hare,

(And what but dream could one do there?)

With melancholy much perplexed

(With grief this creature's often vexed).

"People with nerves are to be pitied,

And often with their dumps are twitted;

Can't even eat, or take their pleasure;

Ennui," he said, "torments their leisure.

See how I live: afraid to sleep,

My eyes all night I open keep.

'Alter your habits,' some one says;

But Fear can never change its ways:

In honest faith shrewd folks can spy,

That men have fear as well as I."

Thus the Hare reasoned; so he kept

Watch day and night, and hardly slept;

Doubtful he was, uneasy ever;

A breath, a shadow, brought a fever.

It was a melancholy creature,

The veriest coward in all nature;

A rustling leaf alarmed his soul,

He fled towards his secret hole.

Passing a pond, the Frogs leaped in,

Scuttling away through thick and thin,

To reach their dark asylums in the mud.

"Oh! oh!" said he, "then I can make them scud

As men make me; my presence scares

Some people too! Why, they're afraid of Hares!

I have alarmed the camp, you see.

Whence comes this courage? Tremble when I come;

I am a thunderbolt of war, may be;

My footfall dreadful as a battle drum!"

There's no poltroon, be sure, in any place,

But he can find a poltroon still more base.

FABLE XXXIII.

THE TWO BULLS AND THE FROG.

Two Bulls were butting in rough battle,

For the fair belle of all the cattle;

A Frog, who saw them, shuddering sighed.

"What ails you?" said a croaker by his side.

"What? why, good gracious! don't you see

The end of all this fight will be

That one will soon be chased, and yield

The empire of this flowery field;

And driven from rich grass to feed,

Searching the marsh for rush and reed,

He'll trample many a back and head,

And every time he moves we're dead.

'Tis very hard a heifer should occasion

To us so cruel an invasion."

There was good sense in the old croaker's fear,

For soon the vanquished Bull came near:

Treading with heedless, brutal power,

He crushed some twenty every hour.

The poor in every age are forced by Fate

To expiate the follies of the great.

THE PEACOCK COMPLAINING TO JUNO.

THE PEACOCK COMPLAINING TO JUNO (2).

FABLE XXXIV.

THE PEACOCK COMPLAINING TO JUNO.

The Peacock to great Juno came:

"Goddess," he said, "they justly blame

The song you've given to your bird:

All nature thinks it most absurd,

The while the Nightingale, a paltry thing,

Is the chief glory of the spring:

Her note so sweet, and deep, and strong."

"I do thee, jealous bird, no wrong,"

Juno, in anger, cried:

"Restrain thy foolish pride.

Is it for you to envy other's song? —

You who around your neck art wearing

Of rainbow silks a hundred different dyes? —

You, who can still display to mortal's eyes

A plume that far outfaces

A lapidary's jewel-cases?

Is there a bird beneath the skies

More fit to please and strike?

No animal has every gift alike:

We've given you each one his special dower;

This one has beauty, and that other power.

Falcons are swift; the Eagle's proud and bold;

By Ravens sorrow is foretold;

The Crow announces miseries to come;

All are content if singing or if dumb.

Cease, then, to murmur, lest, as punishment,

The plumage from thy foolish back be rent."

FABLE XXXV.

THE BAT AND THE TWO WEASELS.

A Bat one day into a Weasel's hole

Went boldly; well, it was a special blunder.

The Weasel, hating mice with heart and soul,

Ran up to eat the stranger—where's the wonder?

"How do you dare," he said, "to meet me here,

When you and I are foes, and always were?

Aint you a mouse? —lie not, and cast off fear;

You are; or I'm no Weasel: have a care."

"Now, pardon me," replied the Bat,

"I'm really anything but that.

What! I a mouse? the wicked tattlers lie.

Thanks to the Maker of all human things,

I am a bird—here are my wings:

Long live the cleavers of the sky!"

These arguments seemed good, and so

The Weasel let the poor wretch go.

But two days later, though it seems absurd,

The simpleton into another hole intruded.

This second Weasel hated every bird,

And darted on the rash intruder.

"There you mistake," the Bat exclaimed;

"Look at me, ain[']t I rashly blamed?

What makes a bird? its feathers? —yes.

I am a mouse—long live the rats,

And Jupiter take all the cats."

So twice, by his supreme address,

This Bat was saved—thanks to finesse.

Many there are who, changing uniform,

Have laughed at every danger and intrigue;

The wise man cries, to 'scape the shifting storm,

"Long live the King!"or, "Glory to the League!"

FABLE XXXVI.

THE BIRD WOUNDED BY AN ARROW.

A bird by well-aimed arrow shot,

Dying, deplored its cruel lot;

And cried, "It doubles every pain

When from oneself the cause of ruin's ta'en.

Oh, cruel men, from our own wings you drew

The plume that winged the shaft that slew;

But mock us not, you heartless race,

You too will some time take our place;

For half at least of Japhet's brothers

Forge swords and knives to slay the others."

FABLE XXXVII.

THE MILLER, HIS SON, AND THE ASS.

The Arts are birthrights; true, and being so,

The fable to the ancient Greeks we owe;

But still the field can ne'er be reaped so clean

As not to let the later comers glean.

The world of fiction's full of deserts bare,

Yet still our authors make discoveries there.

Let me repeat a story, good, though old,

That Malherbe to Racan, 'tis rumoured, told;

Rivals of Horace, heirs in every way,

Apollo's sons, our masters, I should say:

They met one time in friendly solitude,

Unbosoming those cares that will obtrude.

Racan commences thus,—"Tell me, my friend,

You, who the clue of life, from end to end,

Know well, and step by step, and stage by stage,

Have lost no one experience of age;

How shall I settle? I must choose my station.

You know my fortune, birth, and education.

Shall I the provinces make my resort,

Carry the colours, or push on at court?

The world has bitterness, and it has charms,

War has its sweets, and marriage its alarms:

Easy to follow one's own natural bent,

But I've both court and people to content."

"Please everybody!"Malherbe says, with crafty eye,

"Now hear my story ere you make reply.

I've somewhere read, a Miller and his Son,

One just through life, the other scarce begun

(Boy of fifteen, if I remember well),

Went one fair day a favourite Ass to sell;

To take him fresh—according to wise rules—

They tied his feet and swung him—the two fools—

They carried him just like a chandelier.

Poor simple rustics (idiots, I fear),

The first who met them gave a loud guffaw,

And asked what clumsy farce it was he saw.

'The greatest ass is not the one who walks,'

So sneeringly the passing horseman talks.

The Miller frees the beast, by this convinced.

The discontented creature brayed and winced

In its own patois; for the change was bad:

Then the good Miller mounted the poor lad.

As he limped after, there came by that way

Three honest merchants, who reviling say,

'Dismount! why, that won't do, you lazy lad;

Give up the saddle to your grey-haired dad;

You go behind, and let your father ride.'

'Yes, masters,' said the Miller, 'you decide

Quite right; both ways I am content.'

He took his seat, and then away they went.

Three girls next passed: 'Oh, what a shame!' says one,

'A father treating like a slave his son!

The churl rides like a bishop's calf. 'Not I,'

The Miller made the girls a sharp reply:

'Too old for veal, you hussies, and ill-famed.'

Still with such jesting he became ashamed,

Thought he'd done wrong; and changing his weak mind,

THE MILLER, HIS SON, AND THE ASS.

Took up his son upon the croup behind.

But three yards more, a third, sour, carping set,

Began to cavil,—'Biggest fools we've met!

The beast is done—he'll die beneath their blows.

What! load a poor old servant!' so it grows:

'They'll go to market, and they'll sell his skin.'

'Parbleu!' the Miller said, 'not worth a pin

The fellow's brains who tries with toil and strife

To please the world, his neighbour, and his wife.

But still we'll have a try as we've begun:'

So off the Ass they jumped, himself and son.

The Ass in state goes first, and then came they.

A quidnunc met them—What! is that the way?

The Ass at ease, the Miller quite foot-sore!

That seems an Ass that's greatly held in store.

Set him in gold—frame him—now, by the mass,

Wear out one's shoes, to save a paltry Ass!

Not so went Nicolas his Jeanne to woo;

The song says that he rode to save his shoe.

There go three asses.' 'Right,' the Miller cries;

'I am an Ass, it's true, and you are wise;

But henceforth I don't care, so let them blame

Or praise, no matter, it shall be the same;

Let them be quiet, pshaw! or let them tell,

I'll go my own way now;'" and he did well.

Then follow Mars, or Cupid, or the Court,

Walk, sit, or run, in town or country sport,

Marry or take the cowl, empty or fill the bag,

Still never doubt the babbling tongues will wag.

FABLE XXXVIII.

THE COCK AND THE FOX.

Upon a branch a crafty sentinel,

A very artful old bird, sat.