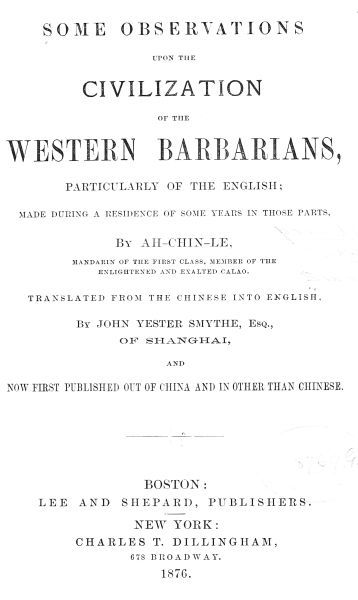

Some Observations Upon the Civilization of the Western Barbarians, Particularly of the English / made during the residence of some years in those parts.

Play Sample

This is a writer who takes the Sea as the scene of his poem. The style is affected; but much liked.

I add below an example of Blank Verse, a form greatly in use:—

"The Morn, exultant, on the mountain tops,

Leads in the Day—and over all the World

Delightful Joy spreads forth his glorious wings!"

This appears to be a parody of Shakespeare, who says beautifully:—

"Oh, see where jocund Day stands tip-toe,

On the distant, misty mountain tops!"

Very much of the poetry is obscured, and spoilt by the influence of the Superstition; and very much by artificiality and affectations. And everywhere there are poor or indifferent imitators of the ancient Greeks and Romans; upon whom the Literati mould their poetic conceits.

Of the Comic and common it is well to read little.Coarseness and indecency seem inseparable from all vulgar humour.

The Descriptive, tinged with the melancholy of the Superstition and Barbaric gloom, is often fine and smooth—sometimes tender and elegant.

I give an extract from an author of no repute, but agreeable; and the more so to me, because inoffensive.It is not defiled by the Idolatry of the Barbarians:—

"Spring-time of life, with open-eyed delight,

Wondering at beautiful earth and sky!

Budding in sweet expectancy, and bright

With smiles and charming grace, and blushingly

Unconscious of a Love, just to be born—

A trembling Joy, which smiles and tears adorn!"

From the same, written in the open country; which, though obscure sometimes, flows on finely, eloquently:—

"Stretched to the brilliant sky, on all sides clear,

Are hills, and dales, and groves, and golden corn—

Whilst in the peerless air, all things are near;

And far or near they each and all adorn!

Here, let us rest, on this fair, breezy hill,

Beneath the shade of this high, spreading beech—

And feel and see that we are Nature's still:

Her Peace and Beauty ever in our reach.

Her calm, majestic glory, harvest-crowned,

Fills heaven and earth, and blends them into one

How vast and solemn bends the blue profound;

How sweet and strong th' immortal gods move on!

Move on, resistless, yet, with tender grace—

Inflexible, yet soft as summer rain—

Intangible—as where yon shadows race,

With nimble Zephyrs, o'er the waving grain!

Ineffable, though murmurs everywhere,

Swell into Anthems of delightful tone;

And smiling hill-tops, and the radiant air,

Rest in expressive Silence, all their own!

And there, by Avon's stream, are Warwick's towers;

And, here, is labour toiling in the fields:

For Lord [Tchou] or serf alike, the patient hours

Give back to Nature all which Nature yields.

Still human hope aspires and will not die;

Will rear aloft its monumental walls;

Informed by Instinct builds as builds the bee—

Mounting secure where stumbling Reason falls!

So Temples rise Immortelles of the race;

Where mouldering with the stones tradition clings—

Touching the landscape with ennobling grace,

And giving dignity to common things.

The day declines, and so my holiday;

Care slumbering by my side awakes again;

Grasps on my hand and leads my steps away—

So rudely rules the Martha of my brain!"

The Martha is a scolding, busy house-wife [bro-msti], taken from an incident narrated in the Sacred Writings. The writer refers to Temples in a pleasing way, and to the "mouldering stones," where, about the dead, innumerable legends survive. Burials are near to the Temples, and the graves are on Holy ground. His reference is comprehensive—meaning the universal Hope of Immortality, symbolized by the lofty Fanes.

I give below a few of the absurdities from the Comic, taken from a greatly esteemed author in this Line.

"Three wise men of Gotham

Went to sea in a bowl [tou-se];

If the bowl had been stronger,

My tale had been longer!"

The meaning of which is, I suppose, that when wise men do foolish things they no more escape the consequences of folly than others.

"I bet you a crown to a penny,

And lay the money down,

That I have the funniest horse of any

In this or in any town.

His tail is where his head should be—

'You bet!Well, come and see.'

And sure enough, within his stall,

The horse was turned—and that was all!"

Another, very ridiculous:—

"There was a man of our town

Who thought himself so wise,

He jumped into a bramble bush,

And scratched out both his eyes.

But when he saw his eyes were out,

With all his might and main

He jumped into another bush,

And scratched them in again!"

This would seem to suggest that a conceited man, having committed an egregious blunder, rashly undertakes to remedy it by one equally unwise. The folly of conceited impulsiveness!

Another, and I have done.

"Little Jack Horner

Sat in a corner,

Eating his Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb,

And pulled out a plum,

Oh, what a good boy am I!"

This is to encourage children with an idea that, if they be good, they shall have plumsIt is very significant of the low culture.As if one were to imagine that the possession of a big plum (riches, or the like) demonstrated the moral excellency of the possessor!

Commentaries and parodies of these Comic trivialities have been written, and, forsooth, their beauties and meanings need exposition!

CHAPTER VI.

OF TRADE, AND REVENUE DERIVED FROM IT.

We have ourselves, in our maritime parts, some experience of the English, as traders [Kie-tee]. Something of their moral character is known, not as traders only, but as representatives of the general civilization of their tribe. It will be a long period before the events of the opium war are forgotten—when these selfish and cruel Barbarians came with their big fire-ships and great cannons, and massacred so many of our province, Quantung! Nor will the slaughters of the people of our Central Kingdom, and the burnings and plunderings at the Illustrious seat of our Exalted, pass out of mind for many generations. Trade! yes, Trade is the Moloch [Kan-ni-bli] of the English; there is nothing (of character) which they will not sacrifice to this Idol. The god by which they mostly swear, and whose name they apply to themselves, knew nothing of trade, and his words, as recorded in the Sacred Writings, condemn every practice customary in it.This inconsistency is always found in the devotees of irrational worship; where formal observances stand for practical virtues.Perhaps dishonesty in trade is no more conspicuous, than immorality everywhere; only traffic touching on all sides, and affecting nearly every interest, carries with it an almost universal debasement. Blind and conceited, it is the custom to speak of our Central Kingdom contemptuously, and to brand our people as Heathen thieves [ta-ki]. We have thieves, and punish them. But how strangely to those of our people who know these Barbarians, this charge sounds! It is notorious that the vile stuff packed up as Tea by our knaves is for the gain of English traders; and that the horribly obscene pictures of degraded artists find a market with the Barbarians! We punish these plunderers when we detect them; but these Christians who would convert us encourage this immorality!

The Law-making Houses are continually occupied (and occupied in vain) to find remedies for the almost universal crime of Adulteration [Kon-ti-fyt] of Food. Scarcely an article of food, or of drink, medicine, what not, escapes this dangerous cheat. To make a larger gain some cheap admixture, often poisonous and rarely harmless, is added to nearly every article. It is not easy to understand how general the moral debasement must be, when a thing of this sort, striking at once at health, and even life, is so common as to be scarcely contemned! To be cheated is a kind of comedy—one expects to be cheated—cheated in his clothes, his wine, his horses, his dogs, his meat, his drink, his beer, his sugar, his tea, his everything! To have been honestly dealt with is a surprise—a thing to be remarked upon. To have been cheated—a shrug of the shoulder—an exclamation—"Of course!" In fact, almost always the cause of a hearty laugh, especially if a sharp trick—or at another's expense! The very laws of trade are based on dishonesty; and a people will not generally be better than their laws.

The High-Caste affecting to despise trade, do, occasionally, in the Law-making Houses (as I have said), feebly interfere with the general rascality. Yet, they are so dependent, indirectly or directly, upon trade or its gains, that they will not do anything to hamper it; and any law which touches the utmost freedom of action in buying and selling, in their opinion, has this effect. On the whole, they say, better a few rogues flourish, and a few people be poisoned to death, than that commerce (an euphuism for rascally traffic) be injured.

That man has a fine nature which traffic, in its best ways, cannot tarnish; and laws should take their colour from the best—not the sordid.The old Romans cultivated the land, and looked with contempt upon traffic.When riches and its corruptions lowered manliness, and Commerce spread through the provinces—still, the Roman jurisprudence based itself upon equity—it did not place trade upon a pedestal above Justice!They made no such Barbarous mistake as to suppose that any business of a people could be more important to its prosperity, than the maintainance of right principle!

The English Barbarians say the interests of the public require a disregard of right; and their famous legal maxim (in the Roman) is Caveat emptor—the buyer must take care—must sharply watch the seller.This is to say, "The seller is to be expected to cheat; and, if the buyer be cheated, let him thank his own stupidity!"The old Heathen Romans made no such immoral rule; they required the most exact good faith upon both sides. The seller could not sell a horse blind of one eye, or incurably, though not always visibly, lame, and to the complaint of the buyer answer, "Oh! I gave no assurance of soundness."

The High-Caste, despising trade of any useful sort, none the less delight in traffic of a high-caste colour. They deal in pictures, equipages, horses, jewels, sculptures, books, dogs, nick-nacks of all sorts; know how to bargain, and understand the tricks, especially in horses, dogs, paintings, and the like, as well as those whom they affect to despise.

The English are, doubtless, successful traders and plunderers. They are rough, and brave, and reckless; and in traffic are as unscrupulous as in predatory ventures. Their conquests abroad have been incidental generally, commerce being the immediate object. But they have never scrupled to use force when it has seemed fittest. The plunder of a people has been found easier, and the returns quicker and larger, than the slower gains of traffic.

For this shameful and cruel conduct, the English and other Western Barbarians find ample justification in their Superstition. For they believe that the peoples beyond the seas are Heathen, and under the ban of Jah. Their Sacred Writings so declare; and that "the Heathen are given to the Saints as a spoil, and their Lands as an Inheritance." Now, these Barbarians affirm that they are the Saints; that the people who do not worship their gods are Heathen; and that consequently they (these Barbarians) have a right to the possessions and lands of these distant and unoffending tribes! And not only this, that these tribes, under the wrath of Jah, and subjects of the Devil and hell, ought to be grateful for the inestimable boon of the Gospel (the Sacred Writings), by which they may learn the way to be saved; may, in fine, become Christians!

Thus it comes about that the intercourse of the Western Barbarians with peoples beyond the seas has been aggressive and piratical. From the earlier part of the dynasty Ming, when these Barbarous tribes first visited the great seas and distant regions in the far West and mighty East, the Pope (then worshipped by all the tribes) gave to two of them, very devoted to his worship and powerful in ships, the whole world of Heathen. This meant all the wide world but that small region in Europe wherein the Pope-worshippers lived. To the one tribe, called Portugals, he gave the whole immense East, and to the other, styled Spaniards, the vast regions in the West. Thus the two were possessed, by the gift of their god, of the whole Heathen world—India and our Flowery Kingdom being portions!

In their many ships, these two tribes, sailing East and West, landed upon the distant shores, and seized upon everything which they could. They thought it pleasing to Jah to put to death those who had offended him, and were already under his wrath and condemnation: the Heathen were justly extirpated, unless they believed and worshipped Jah!

Not very long after this gift to the two tribes, the English and Dutch, having quarrelled with the Romish Priests, refused to worship the Pope and denied his authority.The Dutch first, and then the English, growing more powerful in ships, made distant forays for plunder and trade; and, following the tracks of the Portugals and Spaniards, disregarded their pretended exclusive title to the Heathen. They determined to have a portion of this general transfer of the world to Christians; they were in their own judgment the better, the Reformed Christians, and far better entitled!

Since this enormous Blasphemy [Swa-tze] of the Pope, History, as known to the Barbarians, has been, to a large extent, an account of its consequences. Wars between the contending Christians for the distant possessions, and savage and cruel depopulation, plunder, and subjugation of the unoffending inhabitants. Whole races of men have melted away in the presence of these Christ-god worshippers; and the horrors of the dreadful Superstition, which in the regions of Europe had made man more like the Devil of his Idolatry than anything human, spread, with fire and sword, over the wide world! In the far West, beneath the setting sun, a beautiful and peaceful people, rich and numerous, suffered cruelties too shocking to tell; and in the civilised and populous East, the very name of Christian became a synonym of all that is detestable.

None the less, the English Barbarians, to this day, acting upon these Christ-god pretensions, will insist that this Trade and Plunder is the handmaid of Enlightenment, the chief agent in the preparing of the World for a knowledge of the true gods, and the ultimate salvation of the Heathen!

Trade is, therefore, a civilising agency and a powerful helper in the redemption of mankind from the awful Hell. A few poor Missionaries are sometimes added to the general cargo of means of conversion. The same ship which transports these Bonzes to convert the benighted pagans will, perhaps, have a few volumes of the Sacred Writings, some bad rum, worse muskets (more dangerous to him who shoots than to him to whom the shot is directed), gunpowder, flimsy articles too poor for home trade; to these, add the licentious and degraded sailors; and one sees how well the English Barbarians work to introduce their true worship and save the Heathen!But this is feeble: only a trade-ship.The great fire-ships, with big cannons, full of armed and fierce barbarians, which devastate the populous coasts, and burn and plunder the maritime parts—these are illustrious workers in the spread of the Christ-god Salvation and a lofty Civilization! Thus the very worship of the Barbarians has helped, by its cruel pretensions, to ingrain a wrong notion—one making them immoral and cruel. Taking the Jah of the old, huckstering Jews, as an object of idolatry, the whole people has, in trade, become Jewish, as in much else.

I have referred to petty cheating, and to that wholesale criminality of adulteration. But fraud is very common, and often on an enormous scale. Nor is there any remedy. In truth, it is so common, that, as all hope to have a turn at its advantage, none care to punish heavily him, who, by chance, has been too bold. The fraud must take the form of open robbery, or be of such grossness as to be hardly disguised, before the wrong-doer will be arrested. A man may enjoy unmolested, and even with respect, a great fortune acquired by notorious trickery

So universal is this toleration of roguery, that the Plays and Pastimes are often enlivened by comical illustrations of the various arts, tricks, and deceptions practised. The charlatans, rogues, cheats, and the like, are shown in the Lawyer, the Doctor, the Bonze (low-caste), and other professions and occupations. Endless are the villanies of the Lawyer—the quack pretensions and impositions of the Medical man—the cant, hypocrisy and meanness of the Bonze.

Among the professions and trades, the teacher is a brutal ignoramus, who beats and starves the wretched children under his care; the nurse quietly drinks herself drunk and goes to sleep, leaving the sick man to gasp and die for the drink close at hand, but which he cannot reach; the milkman stops at the pump, and fills up his milk-cans with water; the teaman shows and sells you one sort, but delivers a very different; the grocer says his prayers, hurries to his goods, asks his servant if "the sugar be sanded," "the rum watered," "the tobacco wet down," "the teas mixed," "the small bottles filled," and the like; the tailor sells you more cloth than he knows will be required for your garments, and cabbages the excess; the cabman who knows you are a stranger demands quadruple fare; the innkeeper gives you the meanest room, and charges you the price for the best; and so on through every business of life.

The learned professions take the lead in this exhibition of roguery and immorality.The spectators never tire of these displays of the general rascality.The roguish landlord, the villanous horse-dealer, the artful, knavish servant, the Priest of Low Caste, and the Doctor, afford the most common diversion. The Lawyer is generally diabolic, the Bonze a hypocrite and knave, the medical man an impostor and dealer in medicines of infallible healing power.

Much of this may be referred to the love of coarse humour—but its real base is to be found in the degradation of morals. These representations are types, and would only produce disgust, were not the rascalities represented familiar. The excesses and exaggerations are of the Play—but the types are normal and common.

One great trading place is called the Stock Exchange—another, perhaps more important, styled the Merchants' Exchange. These places are established in every large town, and the business done in them absorbs the attention of traders and people who have any property, throughout the Kingdom.

The dealings [Keet-sees] of the former relate to Certificates and Bonds. These are Pieces of Printed and Coloured Paper, which represent in the words and figures a sum of money invested in a trading concern, or a sum of money which somebody owes and promises to pay. The sum may be quite a fiction, and is usually either never to be really paid, or paid at some very remote day. However, a small sum is promised to be paid every six moons, or in twelve moons—this is for not paying the big sum.

The business of the latter relates to the buying and selling of every sort of merchandise, whether on land, or on vessels at sea.

Other great trading places deal in money, or rather in bits of Printed Paper, which promise to pay money to him who has one of these bits. These places get people to sell them these bits at a price, and then resell at a greater price—or they borrow and lend these bits, paying less for the use than they obtain. Very little money is seen—business is in Paper—another of the ingenious tricks of these trading and gambling Barbarians, perhaps the source of more dishonesty and cheating than almost any other. As the like has no existence in our Flowery Land, it will not easily be comprehended.

The chief of these places for dealing in this money-paper is called the Bank. The Government shares in the advantages of this invention. Its object is to bank up, or hoard, all the real money (gold and silver) which it can get in exchange for the bits of paper. These promise that the Bank will always return the sum of gold which the bit acknowledges to have been received. The man hands the Bank his gold-money to be kept safely till he wishes for it, and the Bank gives him the bit of Paper (which is numbered and recorded in a book). He can carry this in his pocket, but the gold-money would be too burdensome and more easily lost. The Government pledges also that the gold shall always be safely kept, to be returned whenever the bits of paper are returned. This Bank-house is immensely strong and large, built of hewn stone, and is guarded by men armed with swords and fire-arms for fear of the savage and ignorant Low-Castes.

Ordinarily, only now and again, a few persons go to the Bank and wish the gold; because if one wishes it, some one of whom he buys, or to whom he owes, will take the money-paper and hand him the difference—consequently, the paper goes from hand to hand for a long time. Everybody takes it because it is convenient, and because he thinks the gold attached to it is safe in the Government Bank-house. The confidence in Paper is called CreditTo which I shall more fully refer.

Sometimes, when a great many demand the gold, it is suddenly found that the Bank-house has it not! The promise of banking up the gold till wanted in exchange for the Paper has been broken. Down goes Credit—every kind of value shrinks at once; for the Bank has not the real money, and values have been measured by the paper!

The traders and everybody connected with them have incurred debts—that is, made paper promises to pay, like those of the Bank, for property valued on the Bank-paper. It is found that this Bank-paper is too much by one-half—the property has been over-valued in proportion. Still the debtors are required to pay the amount of their paper promises!

It is impossible—ruin and Bankruptcy ensue—the whole trading world is convulsed, and tens of thousands are beggared!

The explanation is that the Bank is allowed by the Government (in consideration of certain advantages to itself) to lend out the gold for usury—that is, it lends a thousand pounds of gold to be returned in three moons, for which use the borrower pays twelve or twenty pounds! It makes its gains by thus using the gold which it has promised safely to keep. It is permitted to do this, because the risk of having much gold demanded at once is small, and from experience the Bank has discovered that if one-third part of its paper-promises of gold is in hand, it will be in little risk of having more demanded! Backed by the Government, it deliberately, for the sake of gain, runs the risk of being a cheat and robber!

Then follows a curious contrivance of these dishonest Barbarians. To save its own moneys and advantages in the Bank, and to save loss or ruin to the owners of the establishment, who are very powerful and numerous, composed of members of the High Castes as well as others—in fact, to save the general wreck of the sham paper-money (Credit) upon which values are falsely based, the Government issues a Law, forcing everybody to receive from the Bank its paper precisely as if it were gold!

Thus, having assisted in one fraud, it resorts to another, to remedy in some measure the evils of the first—extending and perpetuating the evil, which a wise man would remove!

Another remarkable thing is the organised BettingThe Houses where this is done are splendid, and the many people supported in them and by the gains, live luxuriously, and are greatly respected.The gains are, in small measure, also shared by those who put in money from which bets may be paid, when the House loses the bet.

The betting may be about anything.But the chief Houses are those where the bets have reference to length of life or injuries, to loss by fire, to loss by sea, and losses by fraud. If a man wish to bet that he will live say seventy moons, he pays down at once a small sum, and the House accepts the bet—that is, gives him a writing, promising to pay his heirs a very much larger sum if he die before the seventy moons expire. If a man have goods in a shop, he bets, say, one pound to 100 pounds, that they will not be burned during twelve moons—he pays down the pound and receives a writing (as before) that if the goods be burned during the time, he shall be paid the 100 pounds. So on, as to bets upon goods and upon vessels on the seas, upon buildings of all kinds, upon duration of life, and upon the life of another, upon accidents to body, upon honesty of servants—upon almost anything where the thing bet by the Houses is remote in time. This is the great point; for these never pay anything down by way of stakes, but always receive in money the stake (bet) of the other party.

One may readily see how corrupting all this is in its nature, and how falsely conceived. The rascally trader burns the goods, the possessor of a building burns that, the owner of a ship has her wrecked, to get the sums promised upon these events; and trade is promoted upon unsound practices. Even life has been taken by a wretched gambler, who has staked money upon the life of another. The tendency is to these crimes. Nor can there be anything but loss to the public at large; for these expensive Houses and their numerous and richly-living inhabitants are supported by the winnings made, without rendering any useful service. This must be true, even when all bets made by these Houses are paid. But another great mischief follows: they do not pay, and are often only Swindles [Kea-ties] on a great scale! There are those which pay—that is, have so far paid—but as there are bets for enormous amounts far in the future, no one can say that final payments are certain. The great object of all the Houses is to secure as large sums in cash as possible upon events a long way off. The more remote the event upon which the bet is laid, the larger the sum demanded from the individual who bets. He pays—the House merely promises to pay, and cannot be called upon to pay for a very long time! In this way, great sums of money having been got (some bets having been promptly paid to obtain confidence), the House shuts its doors! The rogues share the plunder and decampDecamp is to run away to distant parts to escape arrest and punishment.This is, however, rarely necessary; for such are the cunning contrivances of the Lawyers, who organise these Betting Houses, that very little risk is run—forms of law, slack enough at best, have been so well adhered to, that the rascals escape, though everybody knows that they have used those forms as a cover to more effectually defraud, and then as a shield to more effectually protect! These things are unknown in our Central Kingdom, and are only possible to a demoralised people.

The dealing at the Stock Exchange is mainly only another form of betting. It is hard of comprehension, unless by the InitiatedIt is a distinct trade.Those who deal constitute a secret and exclusive betting Ring, or community.If by chance, when the doors are open, a stranger inadvertently enters, he is greeted with caterwaulings, howlings, "Turn-him-outs," and the like."Smash his hat!" some one cries; and suddenly the stiff head-covering is violently driven down, completely over the face and ears, tearing the skin off the nose, and reducing the thoughtless and astonished stranger to a state of ridiculous helplessness!

Betting is a passion with the English Barbarians.The women, the children, the servants—everybody bets about any and every thing.Horse races, boat races, swimming races, all sorts of games and sports, attended by both sexes, afford endless occasions for the indulgence of it.Yet, after all, extensive, ruinous, and debasing as are the evils of it in these sports and games, the mischief is vastly greater in the Marts of traffic—in the Stock and Merchants' Exchanges.

In these, the dealings are, as I have said, either as to pieces of paper representing values, or as to merchandise in hand or at sea; and, I may add, as to pieces of paper, representing this merchandise, called Warrants and Bills of Lading.

The betting in the Stock Exchange concerns itself with the Paper of the former class, and the betting of the Merchants' Exchange with the Paper of the second kind. All this grows directly out of the Bank paper and the Credit system, before mentioned.

All values are founded upon these nominal promises to pay.But the promises themselves are ever undergoing changes, according to the varying circumstances. The promise to-day looks well—it is estimated at so much; to-morrow it does not look so well—and it is estimated at less worth. Besides, all the gold and silver in the world could not pay a twentieth part of these promises. Thus the fluctuations are incessant. The betting at the Stock Exchange has reference to these fluctuations. One of the betters is interested to have a rise, another to have a fall, of value. One agrees to deliver at a future day, at a certain price; all are interested to bring about a change either one way or another. The man who desires a rise may not be scrupulous as to any means which may produce the rise; and he who wishes a fall of price will eagerly second anything which will have that effect. Consider the consequences upon the honesty and good faith of those who engage in this betting!

The Merchants' Exchange is not so devoted to absolute betting; yet its largest business partakes of that vice. One buys a cargo at sea; another agrees to deliver a cargo three months hence. One sells what he has not, for a future delivery. Another buys what he never intends to receive, deliverable to him in the future. No money is paid, nor received. The buyers and sellers are merely gambling—betting (as in the Stock Exchange) upon the rise or fall of prices! And are interested—the one to advance the price, and the other to lower the price, of the thing dealt in!

Consider the temptation to unfair practices, the inevitable tricks, false rumours, lies, and deviations from honourable conduct involved in such transactions!Reflect upon the consequences to the honest trader, who is, in his very honesty, all the more easily tricked by the unscrupulous!

The stronghold of these various gambling Establishments, and the grand feature, in fact, of the English business life, is Credit—to which I will devote some space.We have nothing like it, nor had the ancient barbarians of the West.It is, perhaps, the most distinguishing thing in the Barbarian life.

As already hinted, Credit means that a Promise shall stand for performance.

It had its rise among the Barbarian tribes, not very long since, and grew out of their incessant wars. Particularly the English, finding they could not pay the armed bands, contrived to get the gold out of the hands of the people in exchange for the Bank-paper, and then, forcing the people to still accept the paper for gold, issued paper to such an amount as Government needed! From that period the people, especially the trading classes, making directly or indirectly nearly the whole, found an advantage in resorting to the same fiction—and the Government could do no other than give to the trader, who could not pay his promise, the same relief which it took for itself—for the Bank. It allowed him to pay what he could, and go on as before! No matter that he paid only one-third part—unless he had been guilty of some extreme roguery, he received a discharge from all his promises, and could begin to make new ones and go on in trade as before!

In this way, the Barbarian community is one wherein a false principle corrupts all.Boldness, recklessness, cunning, to say nothing of positive criminality, are encouraged; honour, delicacy, simple integrity, are driven into obscurity.Let him who would preserve his conscience smooth and clear, a mirror whence divinity be reflected, shun all the marts and ways of trade!

The Revenues of the Government are derived largely from the dealers in the great Marts, and it is immediately interested in the upholding of the Credit of the innumerable paper-promises of all kinds made by these and by the Betting Houses. It is, in fact, the chief supporter of the whole sham—it cannot be otherwise, for the English State rests upon it. The promises of the Government to pay gold can never be kept, and it forces an acceptance of a mere fraction, from time to time, as a sufficient redemption of its promises made generations ago!

Other sums are derived from taxes upon the tea, sugar, and other things largely consumed by the lower castes; whilst rich silks, laces, and costly things used by the High-Castes are not taxed.But then the taxes are levied by the High-Castes!

A great revenue is collected from the excise, a tax upon the beer, drunk in enormous quantities by the lowest Caste. To stimulate the consumption of this article and increase the revenue, Beer-shops are to be seen on every hand, and the drinkers everywhere. Drunkenness, wretchedness, riot, disorder—these flourish as the Beer-shops increase; these are the associates of those places! Yet in vain do good Englishmen try to remove these evil densWhat are the efforts of these few in the midst of a general debasement—a debasement which takes, without shame, a share in a traffic so vile!

I have spoken freely of the dishonesty of the Barbarian trade and business—a dishonesty to be expected when one broadly views the whole ground of their Society. Still, natural equity and its instinct, especially when the mind is more or less cultured, will always prevent absolute dissolution—thieving and roguery will be restrained in tolerable bounds. A man of genuine integrity finds traffic no good moralist in the best of circumstances. He needs the support of the State, or he will fight an unequal battle, and be forced by dishonesty to retire. The Barbarians are not yet sufficiently enlightened to raise the measure of honesty. The Government and the people are one in this. They do not perceive that the evils under which their industry, their peaceful pursuits, and all their interests suffer, are those inseparable from a bad superstition and false principles—these extend everywhere and into everything. Misleading in Statesmanship [Lan-ta-soa], in dealings with distant peoples, in due ordering and educating the people at home—stimulating wild speculation and extended confidence (credit) at one time, only to be followed by disastrous collapse, excessive distrust, and wretchedness, soon after! Giving, in fine, to Barbarian society that aspect of restlessness, that apparent but often vicious activity, that indescribable hurry and confusion, that unhealthy excitement, unknown to an orderly and industrious people, whose order and industry are grounded upon the simple and direct rules of reason and truth.

CHAPTER VII.

SOME REMARKS UPON MARRIAGES, BIRTHS, AND BURIALS.[HI-DY].

In our Flowery Kingdom when a man marries he pays to the parents or relatives; but with the Barbarians the woman pays to the man. Women are such costly burdens that men demand some compensation for undertaking to keep them; and the relatives of women are glad to get them off their hands at any price.

There are in England four great Castes, which contain the whole population.The habits of the Castes differ, though you will observe certain characteristic features common to all.In order to understand more clearly the remarks which follow, it will be convenient to speak of the division of Castes.

The first—High-Caste.Those who do nothing useful and pass their time in mere self-indulgence.

The second—High-second Caste. Those who do but very little, and come as nearly as possible to the selfish existence of the first

The third—High-low.Those who are obliged to work more or less, but are ever longing to attain to the idle selfishness of those above them.

The fourth—Lowest Caste (Villeins).Labourers, not long since serfs, and still so in effect.

The fourth Caste is so low down as to be usually disregarded altogether, in any account of the people, though included in the count taken of the population by Government. They may amount to nearly a half of the whole. They are rarely styled people at all. They are designated by many contemptuous names, of which the more common are my man, navvy, clown, clod-hopper, parish-poor; boor, rough, brute, and beast are frequent, especially when any of the despised Caste slouch too near, or happen to touch a Higher Caste.

When a man of the higher orders thinks to take a wife, he sees to it that she will bring him money enough to compensate the cost.He dislikes to part with his easy freedom and yoke to himself a being as selfish, frivolous, and useless as himself.

He may be broken in fortune and notorious for immoralities, yet, connected to the Aristocracy, he knows that he may demand a large sum if he will take for wife a woman a little lower in family than himself. She must be of High-Caste, but not of the highest.

The woman's relatives say, "Well, he is fast; but marriage will settle him.His father, you know, is second son to the Earl of Nolands, and his mother was a sixth cousin to the Duke of Albania, who has royal blood in his veins.I think we may make a large allowance for such a desirable match."It does not occur to the speaker, at the moment, that the royal blood coursed through very impure channels in the case cited.

It is an object eagerly sought by low rich to buy for their daughters a High-Caste husband; and men of this kind, ruined by gambling, loaded with debt, often degraded by vice, deliberately calculate upon this ambition to repair their fortunes, and get comfortable establishments.

The marriage ceremonies do not differ very much from ours, in some things; but it is very different before the ceremony. With us, the woman is unknown to the man; but with the English, the man has every opportunity of seeing her, and knowing her very well indeed. Our notions could not admit of this, but it has a convenience; it would prevent the disappointment occasionally arising, when, on opening the door of the chair, our new husband finds a very ugly duck instead of a fine bird, and hastily slams the door in the poor thing's face, and hurries her back to her relatives as a bad bargain! However, this advantage to the English husband is not so great as it seems; for the woman is too cunning to discover much till she has secured her game. Unless, therefore, the man be a very cool and practised lover [mu-nse], he is likely to be rather astonished when he sees his bride—and he cannot slam the door against her!

The Bonzes, generally, perform the ceremony before the Idol in the Temple. It is deemed to be important to have the marriage invocations pronounced. These are barbarous in the extreme; most indelicately alluding to those things which decorum hides, and calling the gods to aid the conjugal embrace—no wonder that the bride wears a veil!

The great bells ring in the lofty towers, the loud music strikes up, and the marriage procession enters the Temple; and any one may follow who pleases, so he be well dressed. In the great towns, the beggarly rabble—chiefly children and half-grown youths of both sexes, with old women and men—crowd about the Temple gates, but dare not enter. When the cortège leaves, this rabble clusters round the wheels of the carriages, turning over and over upon hands and feet, standing on head and hands, rolling and crying out, in the dust or mud of the street, begging for pennies (a small English coin). When these are thrown amongst them, they ridiculously scramble and tumble over each other, seeking amid the dirt for the coins, like so many carrion-birds upon garbage.

Arrived at the home of the Bride, a great feast is eaten, with wine and strong drinks. All make merry; whether because it is so desirable to be rid of a female, or because of the liking which the Barbarians have for eating and drink, I know not. The feasting over, all take leave of the new pair, the bride being addressed by the title of her husband. The Bride is kissed, the husband shaken [qui-ke] by the right hand, and good wishes given. On leaving the portal for the carriage, old shoes [ko-blse] and handfuls of rice are thrown after them; the rabble roosting about the areas and railings rush pell-mell after the old shoes, begin their tumblings about the street, and howl for more pennies. The rice-throwing is no doubt Eastern in origin, and has an obvious meaning; the old shoes refer to something in the Superstition—probably to appease the evil imps, who delight in mischief and are amused by the absurd squabbles of the beggars.

The Honey-moon begins at the moment when the pair enter the carriage and the old shoes are thrown after them. The horses start, and the newly-married are whirled away into the deeps of an Unknown! You may, perhaps, catch a glimpse of the bride, wistfully stretching her neck and turning her eyes, dimned with tears, to the door-steps where stand those with whom she has lived—and whom she now, it may be, suddenly finds are very dear to her! But the husband has grasped the waist of his new possession, and is absorbed in thatHe has before been the owner of horses, dogs, and the like, which have worn his collar—this is another and very different bit of flesh and blood; none the less, however, branded as his own exclusive possession, and ever after to bear his name! He understands so well the mere fiction of this ownership, that he is by no means sure that after all he have not made a bad bargain—it may prove too costly, and be by no means either useful or obedient! However, with his arm about his wife, just now he hardly realises these doubts, but feels, or tries to feel, ecstatic—as he ought.

The Honey-moon thus begun, ends exactly with one moon. It is a received opinion that the Incantations at the rite exorcise the Evil One for the period absolutely, though he may (as the Barbarians express it) "play the very Devil" with them afterwards!

I was told that the Honey-moon was so called because, during the Moon, the new couple fed wholly on honey and drank weak tea! There is some mystery attached to it, for my questions were always answered with a doubtful look. I had no opportunity of absolutely solving it—though my observation led me to judge that the honey diet did not agree with people—in truth, I wonder at its use. I have seen a bride after her return, thin, pale, peevish, who had left round and rosy; a bridegroom before the moon jolly [Qui-ky] and devoted to his bride, return taciturn, careless, forgetful to pick up a fan, or to place a chair for his wife, and even (on the sly) kick the very poodle which he before-time caressed! and when the wife pouting has said, "Out again, George," he has replied, lighting a cigar, "Yas, I must meet the fellahs, you know!"

The best hint on this subject which I ever got was from a married Englishmen, who to my query said, "Ah-Chin, my dear fellah, call Honey-moon Matrimonial Discovery, and think about it, ha!"

As the honey-eating and tea-drinking are to go on, whilst the new couple are quite retired by themselves, away from their friends and all usual pastimes and occupations, necessarily they have only each other to look at with attention. The honey-eating is trying enough, and needs, one would think, all the relief of gaiety and occupation possible! But no, it is only to eat and to closely watch each other!

I wonder no more at the changes which I observed.Nor do I wonder at the improved appearance of the couple when, after a few weeks of rational life in usual pursuits, something like the health and cheerfulness of old returned!

Yet I was informed that very many couples never recover from the Honey-moon (as my informant had it, Matrimonial Discovery), but from bad grew worse, soured and sickened entirely, could not, at length, endure each other, separated by consent, or sought the Divorce Court!

The thing, therefore, seems characteristic of the coarse humour of the Barbarians, who appear to find a comedy in an absurd, irrational trial of respect and affection, dangerously near the tragic at best, and often absolutely so! Absurd and irrational after marriage—one can conjecture its use before!However, it is quite of a piece with the general disorder, and want of knowledge and practice of sound principles.

When a child is born, the event is duly announced in the public Gazette, and relatives send compliments. When the infant is about eight days old, it is taken to a Temple to be baptised and christened. It is a singular rite, and one of the most astonishing in the Superstition. The Bonze who officiates before the Idol, takes the little thing upon his arm and sprinkles some water upon its face. At the moment he does this, he makes a curious Invocation to all the three-gods-in-one of the Worship, and pronounces aloud the Christian name of the babe, by which it shall ever after be known. This is called Christening, that is, making a Christian of the infant. The ceremony, it is believed, exorcises the Evil One, and makes it very difficult for him to get hold of the baptised (no matter how diabolically he may act) in after life—the water, duly made holy by the Priest, is a barrier over which Satan, with all his wiles, shall find it well-nigh impossible ever to get—some Bonzes say it is absolutely impossible!

Women, as soon as strong enough to attend the Temples, are churched (we have no term of the kind), a rite much like an ordinary thanks offering, for the happy deliverance and new birth. The Bonze makes Invocations, and refers to the various superstitions and barbarous pretensions of the Worship, devotion to which is inculcated under fearful penalties.However, on all occasions in the Temples, these dreadful intimations of Hell and the Devil are most frequent!

When a death occurs, it is also announced in the public Gazette, with honours and titles; and, if a High-Caste, with a long notice of the chief events of his life, and loud praises of his valour, as where he led, in his youth, a hand of fierce Barbarians like himself to the plunder and burning of some distant tribe! His virtues are also proclaimed—to the astonishment of all who knew him!

The tombs of the High-Castes are something like those of our Literati—though, instead of being in the country amid the pleasing scenes of Nature, they are generally in the holy grounds of the Temples, and even within the Temples themselves—for the superstitious Barbarians think that, even after death, the body is safer from the Devil there than elsewhere! But the common people lie hideously huddled together, without distinguishing marks (or with so slight as to be quickly obliterated), and are soon totally neglected and forgotten—happy, indeed, if their despised dust may mingle with holy earth within the precincts of Temples.

The Bonzes pray and sing the usual invocations and prayers over the body of the dead, before it is placed in the tomb—but there is no real respect for the dead—it is not to be looked for in the rough, barbaric nature. In our Flowery Kingdom regard for the dead, respect for their memory, tombs carefully preserved amid the quiet groves of the country, tablets and busts set up in the Halls of Ancestors—these are ordinary things.With the English, in general, the dead is a hideous object turned over to the undertaker and his minions to be buried out of sight, as soon as decency allows!With us, the poorest will have the coffin ready, prepared, and carefully honoured and cared for.With the English, the thought of one is repulsive, and he looks upon it with loathing!No doubt the horrid superstition has much to do with this feeling.

The undertakers (a hateful crew) drape everything in black. They take possession of everything, and turn the whole house into a charnel. They place the defunct (as the Barbarians, with a kind of contempt, call the dead) in a black vehicle, drawn by black horses, and draped with black cloth—black feathers and scarfs, hideously flaunted, with men clothed in black, attend—the dismal Hearse, with its wretched accompaniments, disappears—but only to disgorge the body. Soon after these Vultures maybe seen returning, seated upon the Hearse, clustering there, like carrion birds, who have gorged themselves! When they have feasted and drunk at the House of Woe (woe, indeed, whilst deified by them), and generally spent as much money as is possible—they, at last, disappear—and the family breathe again!

An English Barbarian once told me that these creatures, in tricks of plunder and cheating, surpass the Lawyers; in truth, the fashion is to show respect to the dead by a lavish expenditure in black draperies, and is almost wholly confined to that. It is an object to speak of the cost as a measure of that respect! The whole thing being a sham, though a most disagreeable one, the Undertaker sees well enough that he might as well pocket a large sum as a small one. A certain sum is to be spent, for respect, not for any tangible thing. The Undertaker takes care to furnish more respect than anything more tangible—and to charge for it! In fact, the mode of plunder is reduced to a system; and it just as well satisfies the real purpose—which is, to do all that is customary, and to submit to all the customary cheating.

After the family have really got rid of the Undertaker, then comes the Lawyer, with the Bonze, to read the Will of the deceased. This is a new departure (as the English call it) in the family voyage of life. The Barbarian law is so erratic and confused, that no one knows what the dead man may have ordered to be done with his money. His Land goes probably to the eldest son, or nearest male relative; and, if it be all the property, younger children may be left quite beggared. The Will begins with some absurd superstitious formula; and, prepared by a Lawyer, is only intelligible to him. He, therefore, is present to read and to explain. For no one is supposed to comprehend its jargon but the initiated. The Will is read, therefore, to those who only imperfectly catch its meaning; and when a name is reached, the party listens with an eager attention. He may be one who, by nearness of blood, or by the nature of his relations with the deceased, expects to receive a handsome gift. When he, at length, from the mass of verbiage, dimly gathers only a gold ring or a gold-headed walking-stick, and sees some one, scarcely heard of, carry off the goods long waited for, he scarcely appreciates the loving token of regard ostentatiously bestowed upon him! Nor is his smothered rage extinguished by the satisfactory expression of other relatives, who whisper, "Well, he cringed and fawned to little purpose after all!"

From this Reading of the Will begins a new era in the family. Quarrels there may have been, but a common centre of influence and interest kept the contestants in order. But now, nobody satisfied (or only those who expected nothing, and got it), all are in a mood to attack any one, to charge somebody with meanness, with treachery. So bitter animosities spring up. Lawsuits, hatreds; families are severed; old friendships sundered; the lawyers stimulate the broils; and, at last, very likely the Will and all the property covered by it get into Chancery! When I have said this, I have said quite clearly, even to the Barbarian mind, that here all are equally wretched and equally impoverished, excepting the Lawyers!

The power of the dead man, by a Will, to cut off a wife or a son with a shilling (as the Barbarians express it), is monstrous. Then the unjust law, by which the next of kin takes all the Lands of a deceased, works endless misery. Think of younger brothers and younger sisters being forced to depend upon the cold charity of the oldest, who, by mere accident of birth, takes every thing! And not only this, but some distant male relative may cut off the very means of subsistence from females very near, and throw them helpless, and too poor to buy husbands, upon the world! A disgrace and shame too shocking for belief.

Then, too, the wife's relatives may have paid to her husband the very money which, by the Will, is coolly handed to a stranger!

Such anomalies are unknown to the customs of any well-ordered and civilised people.

The new Widow usually remains shut up in her house, inaccessible to all but her children, her servants, her Bonze, and her Lawyer, for twelve moons exactly. During this time she devotes herself to the prayers and invocations of the rites; and will not so much as look at a man, unless the exceptions named. She is wholly draped in black; her children, her servants, even her horses and dogs, are in black. She entirely quits all the vanities of life; she only allows her maid to smooth her hair. She suffers her hands and face to be washed, but never paints her cheeks, nor tints her eyelashes. If she go abroad, it is to the Temple to pray, or to the tomb (in some cases) of the "dear departed," covered from head to feet in thick black, followed by a tall footman, all black, bearing the Sacred Rites. If a man come too near, he is waved, with a solemn gesture of the hand, to remove away: this is the special duty of the flunkeyIf, by any chance, the widow in her march happen to lift her thick veil, and catch the eye of a man,—ah!how dolorous must her prayers be!

Precisely at the stroke of time, when twelve moons have gone, the widow drops all the habiliments of woe, and is herself again!—that is, a woman in search of a husband!—if she have not, from clear, sheer desperation, and want of anything better to do, already pledged herself to her Priest or to her Lawyer. Now, free and at liberty to choose, she may wish to look further; but it is probable that "the inestimable services" of the Lawyer, in her time of misery, hold her to recompense; or that the Priest, attentive to the precept of the Sacred Writings (which commands that Widows shall be comforted), has so well obeyed, that the Widow, completely solaced by the dear, good man, gladly rests with him!

The great book of Rites and Customs regulating the conduct of widows, of widowers—in fact, the observances of Society generally—I have never been able to see. It is in the care and under the constant supervision of a High-Caste of exalted state, from whose authority there is no appeal, styled Missus GrundyI think a stranger can in no case be allowed to see this Illustrious, nor the Book.Indeed, I was told that no one, not even Royalty itself, could inspect the Book, nor challenge this authority.It is hereditary in the mighty Grundy family; and the head of the House is believed to be infallible in social observances.Another remarkable thing is, there is never a failure in the succession—a Grundy is always on hand!

Now, Missus Grundy speaks with more tolerance as to Widowers: they are not absolutely liable to decapitation if they marry again in less than twelve moons. Widowers, for reasons I do not know, are favourites with the Barbarian females; and young women with money will give all they possess to get a Widower, even when he have many children. It may be because of the love for the "pretty dears," as the young ones are called; but, whatever the cause, the fact is certain. To gratify these gushing females, Missus Grundy allows a Widower to marry in a less time than twelve moons: it is so desirable that the pretty dears should have the tender care of a new (step) mother!

As the Barbarians have no Halls of Ancestors, where the family preserve with dutiful care the records of the virtuous dead—inscribed on tablets of brass or polished stone—and where, arranged in due order, stand the marble busts of those more distinguished—they soon forget the dead.

The High-Castes sometimes set up monuments in public places; in Temples and the Temple-burial grounds; and inscribe thereon lofty panegyrics, as false in fact as they are bad in style—and no more thought is given to them. In truth, these monuments are always considered to be to the honour of the living—who take the occasion to display their own wealth, characters, titles, or taste.

The Lower-Castes do but little more than hurry to the grave the dead body, and dismiss the "unpleasant topic" as quickly as possible—imitating as well as they are able the High-Caste, by setting up a Stone-slab, carved with a ruder but not truer description. Couplets in verse are often added; and, as giving an idea of the humorous and coarse conceit of the Barbarian mind, I will insert some of these Inscriptions

Often the slabs are flat upon the ground, and the tombs ruinous and neglected; in fact, very generally the burial-places, though holy, are in a wretched condition—tombs fallen, stones and tablets prostrated, graves quite worn away by the careless feet of passers; the whole place wearing a sad air of utter neglect and forgetfulness. One discovers a better culture making some progress, by curiously regarding these stones, inscribed with memorials of the dead. They have slowly become less uncouth, less barbarous, and less devoted to the wildest vagaries of the SuperstitionHowever, this observation is to be taken in a very general sense.

Often, in the country, I have stumbled upon a singularly-built old stone Temple—standing quite alone, with the tombs and the tablets of the dead, clustering beneath the shadow of the lofty, square tower of hewn stone.Upon the hill-side, with a lovely view of hills, and soft vales, and rich fields of ripening corn, and scattered groves—with green meadows divided by flowering shrubs, where the flocks and the cattle fed.Near by, orchards, white and pink in blossoms; and all the air fragrant with a delicate perfume.At my feet, a few houses nestling among lofty elms—far away to the West, the sun shining above with slanting rays across a wide expanse of beauty—sitting upon a stone bench, beneath the ivy-covered Temple-porch, I have looked upwards to the serene sky, and outwards upon the tranquil and lovely scene; and I have known no Barbarian rudeness, felt no Barbarian Idolatry.The solemn Temple, eloquent in silence, the unbroken rest of the dead, the calm and delightful presence of Nature, these were here, these are there; man unites his grateful worship across the wide world—the Sovereign Lord is worshipped, though darkly, by these Barbarians! And in this worship (in time to be purified) we are one!

But I must give some specimens of Barbarian Inscriptions—by them called Epitaphs, when written to the dead—taken from tablets in places of burial.

"Here lies an old maid, Hannah Myers;

She was rather cross, and not over pious;

Who died at the age of threescore and ten,

And gave to the grave what she denied to the men!"

Another:—

"Poor Mary Baines has gone away,

'Er would if 'er could but a couldn't stay!

'Er 'ad two sore legs, and a baddish cough,

But 'er legs it were as carried her off!"

Here is one which refers to certain mineral [zi-kli] waters, prized by the Barbarians for curative properties:—

"Here I lies with my four darters,

All from drinking 'em Cheltenham Waters;

If we 'ad kept to them Epsom Salts,

We wouldn't a laid in these 'ere waults."

Here seems to be one, not uncommon, which covertly shows its disdain for the gods of the Superstition:—

"Here lie I, Martin Elginbrod—

Have mercy on my soul, Lord God!

As I would on thine, were I Lord God,

And you were Martin Elginbrod!"

The following is most absurd:—

"Here lie I, as snug

As a bug in a rug!"

And some equally funny relative placed near, but not probably pleased with him, adds:—

"And here lie I, more snug

Than that t'other bug!"

A slang term for a low, brutal fellow.

The following turns upon the word lie [pha-li], and the word lie [pu-si]:—

"Lie long on him, good Earth—

For he lied long, God knows, on Thee!"

This is ridiculous in manner of quoting from the Sacred Writings; and adding, without proper pause, the death of another person:—

"He swallowed up death in victory

And also Jerusha Jones

Aged sixty!"

Here follow references to the Superstitious horrors:—

"Whilst sinners [kri-mi] burn in hell,

In paradise, with Thee, I dwell!"

Another:—

"When the last trump doth sound,

No more shall I be bound

Within the earth;

My soul shall soar above,

To shout redeeming love,

Which gave me heavenly birth!"

This I fear will be scarcely intelligible. The last trump refers to a statement in the Sacred Writings, where it is said that a great Trumpet shall awake the dead, and so on. Probably, the remainder may be guessed by attentive readers of these Observations

The next intimates that the couple had been quarrel-some, but had, at last, silenced their bickerings in a common grave:

"Here lies Tom Bobbin,

And his wife Mary—

Cheek by jowl,

And never weary—

No wonder they so well agree:

Tim wants no punch,

And Moll no tea!"

These refer to occupations.By a cook:—

To Memory of Mary Lettuce:—

"If you want to please your pallet,

Cut down a lettuce to make a salad."

By a sailor [ma-te-lo]:—

"Here lies Tom Bowline,

His timbers stove in—

Will never put to sea ag'in!"

"Below lies Jonathan Saul,

Spitalfields weaver—

That's all!"

Spitalfields is a famous place for silk-weaving [tni-se-ti].

I need not make any criticism upon these things.They would be impossible to our better culture and refinement. Our Book of Rites would not suffer such low conceits to see the light if, by any chance, any one should indulge in them privately.

It may be said in fairness that these are specimens of the low, and with these there is less indecency than formerly. There are, however, abundant samples even among the Higher Castes, of things in really as bad taste, though in neater language—quite as offensive, but to the feelings of right reason rather than to those of literary delicacy. They refer to the canons of the Idolatry, and seem, to a stranger to that Presumption, quite incredible.

However, one must reflect upon the effect of superstition, long ingrained, and "born and bred" till its enormities are as familiar as the most harmless images; and its blessings appropriated, and its curses distributed, with an equal equanimity!

I have not referred to the great Pageants when High-Castes are buried who have been famous as Braves, either in distant forays with armed bands upon the Heathen, or among Christian tribes of the Main Land. Or, perhaps, some high chief who has ordered the great Fire-ships in burning and plundering beyond the Seas. I have not referred to these, because they are merely shows, and do not in any sense apply any especial characteristic. One thing I have remarked—there seems to be no respect for the dead, they are immediately forgotten, and the very monuments ordered to be set up probably never appear; or after so long a period, that a new generation wonders who can be meant by the figure which rises in some public place! And when these are once placed on their pedestals, neglect falls upon them in a mantle of indescribable filth. Even royalty cannot have the royal robes of marble so much as washed by the common street hydrant [phi-pi].

It is impossible not to feel that the cold and coarse feelings of the Barbarians are, in respect of the dead, rendered more repulsive by the horrid features of the Idolatry. In this there is so much to brutalise and render callous, that it is only as it is disregarded, that the natural human feelings come into play, and tenderness and delicacy find expression.

CHAPTER VIII.

OF ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND SOME WORDS ABOUT SCIENCE.[KRI-OTE].

Until recently the Barbarians had no proper style of Architecture, unless in Temples, Castles, and Ships. The dwellings, even in cities, were as ugly and inconvenient as it is possible to conceive.

When the great Roman civilisation disappeared, the barbarous tribes for many ages so slowly improved, that the aspect of common life remained savage.The Priests of the Superstition, however, saved some tincture of Roman learning, and brought from Rome some of the older knowledge.These, however, directed their minds to the erection of Temples, and edifices designed for the objects of Priestcraft.

Then arose those structures, truly wonderful, in stone, which exhibit so clearly the character of the gloomy Superstition: at first like those of Rome, but in time added to and changed, till at length the vast Temples, truly gigantic, called Gothic, arose.

These are like huge phantasms of carved stone, rising into the sky. Huge walls, buttresses, turrets, immense clusters of columns, vaulted and lofty arches, long aisles, lighted by strangely-tinted windows, carved masses of stone in prodigious strength, leaping, flying upwards, upwards, in grand confusion, and yet upon a strange, wild plan! —giving expression to an imagination only known to these dark and strong Barbarians. Externally, on all sides these Temples are monstrous idols in stone, stuck most curiously upon corners, high up in niches, on turrets and battlemented [trit-ti-sy] walls, over the sculptured, grand portals, everywhere—chiefly diabolic, exceeding all the dreams of a mad and dreadful frenzy, yet borrowed from the Superstition and illustrating it! Others surmounting these dreadful things, angelic and serene—as if, after all, the human instinct spurned all the low and horrible intimations of things too foul for expression, and yet so frightfully attempted, in ghastly and grinning stone!

The Roman-Greek types knew nothing of such—how clear and beautiful these stood out, cheerful and clean, in the pure sky!

As art found this sort of expression in the structures devoted to the Superstition, so in the buildings for the chiefs of tribes the same spirit directed, though modified by the object. In these art found pleasure, and the barbaric mind delight, to pile up lofty Castles of huge stone—dark, menacing—where all was for strength and to symbolise Force, and nothing for refinement, nor even comfort. These great structures are now, for the most part, crumbling away; not from change of barbaric spirit in the love of Force, but from the uselessness of the Gothic forms in the presence of big cannons.The Roman Architecture, somewhat altered, is generally revived in buildings of importance.Yet the Priests build much as before—dropping off, however, the more hideous of the grinning idols. In this unconsciously giving a sign of the decay of the Idolatry itself. For when all its horrors shall have disappeared, the morality and the simple worship of the Lord of Heaven may remain. The improving condition has improved dwellings, particularly of the Higher Castes. The poor still grovel in huts and hovels, often too offensive for the healthy growth of anything but pigs. Among the Low-Castes, in great towns, the filth and stench are quite insupportable.

In ships the English Barbarians pride themselves to be foremost. Upon this subject we may fairly give an opinion. There are others quite equal, and those of the Starry Flag often superior.

At present the style is changing, and from wood are becoming iron, with such massive sides of thick steel, that no shot fired from any cannon shall be able to break through!So these English think to sail with these huge iron machines into the waters of any people and force submission.For the mighty cannon, shooting out vast fiery balls of steel, are expected to knock to pieces any Castles and utterly burn and destroy any city.And sheltered in these impregnable, swift, floating fortresses of steel, these Barbarians expect absolutely to dominate over all the Seas, and to sink everything which dares to oppose.This supremacy is already vaunted; and all the taxes which can be got from the people, from the tea and beer which they drink, from the tobacco which they smoke, from the letters and papers which they write and use in affairs, and from a share of their daily toil, are devoted (after handing a certain portion to the Queen and the High-Castes for their pleasures) to these big, floating machines of war, to the huge cannons, and to arm and pay the sailors and soldiers, that this domination be absolutely assured! Still, so far, none of these terrible vessels have proved of any use, as they can neither float nor fight; or, if they float, turn bottom upwards at a small breath of wind, and, if moved to act in concert, are so unmanageable as to be only terrible to each other! The sailors, therefore, dread them as unfit for the sea, and as Iron Coffins to poor Jack, who is forced to go into them!

The introduction of Steam has only rendered the Western Barbarians more conceited and more miserable. On nothing do they pride themselves so much as upon the tremendous Force, which they have acquired in the various Arts, by the use of steam. They, in this, as in other similar inventions, mistake the nature of the thing used and its effect. They think themselves wiser because they move faster—as if the hare be necessarily wittier than the ox; and more civilised, because more powerful—as if the rhinoceros were to be preferred to the horse.

At this moment, the Barbarian tribes of the West are devoting all their energies to this single notion of Supremacy. Force is absolutely the most coveted thing—to be strong, the only desirable thing. And the acme of that civilisation of which they boast, glitters only with polished steel, towering high, bristling with terrible weapons of destruction!

There are canals not much used, and not commonly of good depth and width. The High-roads are nearly as good, in some parts, as those in our Flowery Land; but more frequently quite inferior, being either very dusty or muddy. They have none of the conveniences for the shelter or rest of travellers, provided everywhere by our Illustrious; nor are the signal towers and fine shade trees, which give such beauty to our roads, to be seen, excepting occasionally, and quite by chance, the latter.

The Bridges are insignificant, as a rule, owing to the littleness of the rivers; but they are handsome and strong, built of stone, in the Roman style. They span the rivers, the canals, and form viaducts [pa-se-gyt] for roads of Iron. Upon these roads, passing sometimes over the dwellings and streets of towns, move rapidly the long chain of carriages, drawn by steam-engines, conveying many people and much merchandise. These iron roads are numerous, and the works and buildings connected with them very great and costly. The Barbarians greatly vaunt the usefulness of these roads; but the rightfulness of their opinion is by no means apparent. They break up the quiet and the accustomed industries of the people; excite agitations, produce restlessness and expense, accumulate too many here, and depopulate and render meagre thereThey crowd the cities with the poor, and leave the rural districts empty; the towns are overburdened and the fields untilled.They foster the extravagances of the rich and add nothing to the comfort of the common people.It is said that in the saving of time is a saving of money.But it is to be considered that this ease and rapidity of movement is not always usefully directed. It may be, and it is, largely used only to waste and dissipate money and time. It is said to save material measured in relation to effect. This is not clear; for, although a ton be moved far quicker to a given point, who shall say that the ton moved by usual means would not, all things estimated, be as economically moved, and with as good result to the common weal?

The real question is not considered, which is—Have Iron-roads added to the useful means of the people?Consider the cost, and say whether such vast expense in other mode or modes of outlay would not have produced means more beneficial.

How much more numerous and better roads, vehicles, buildings for the poor, improved culture, tools, larger areas of recovered lands, new fertilisers, new and numerous schools—innumerable details of improvement—had the intellect, time and money directed to these roads been directed to the many needs of a people! The good, then, is rather the good which activity of brain and outlay of money naturally effect—possibly that activity and expense have not been most usefully employed in Iron-roads—indeed, very probably not to the good effect of a more naturally ordered expenditure. But the English, seeing the effect of a prodigious activity and employment of money spread over many years, place it to the credit of a thing—Steam; never considering at all whether the thing has been necessarily the cause, or only the accident.To what effect, during the same time, might that same energy and money have been applied!The new power stimulated energy, and possibly misled it. It may be said that steam did its service by giving this stimulus. Probably not so. The question is, Has Steam after all misled—fallen short, in fact, of those effects which the usual and less novel forces would have produced?This is an unanswered question.

In the industrial arts the English are not remarkable. They are good in fire-arms and curious in weapons, as may be expected. They are expert in making barrels and vessels to hold liquors from wood; need, which they call the mother of invention, made this art a necessity; such is the prodigious quantity of beer which they consume. In dress-fabrics, in tools, in furniture, in metals, they show no more skill than our artisans, and in many articles not so much. We have arts, useful and beautiful, unknown to the Barbarians; they have things of mere show and luxury for which we have no use. In what is called Fine Art—that is Painting and Sculpture, particularly—we have but little to compare. By Fine Art is meant what is impossible to us; it is for the most part intolerable to us.

Think of the Illustrious of our Flowery Kingdom crowding into Halls, glittering with gilt and showy colours, to see there, arranged upon the walls and standing upon marble tables, great pictures of women and of men, often naked or nearly naked—wholly nude figures, mostly of women, in all attitudes, carved from marble, or made of a fine baked clay!Not only so; but the illustrious mothers, wives, daughters, and female friends, accompanying the men to the spectacle!The young man and the young woman together gazing upon the nude and flesh-tinted voluptuous female, glowing in the picture! No; we give no such encouragement to fine Art! Yet our painters compare favourably with those of the Barbarians, in such proper use of the Art as is allowed by us.

For the same reason, as Sculpture with us is only permitted where useful or innocent, it does not reach after such effects as with the Barbarians; where a naked figure of a young woman, done in marble to the luxurious taste of a wealthy High-Caste, will command a great sum. None the less, our Artists can execute with fidelity, as our Ancestral Halls will show.

Copying from the ancient Romans, in their most wanton and luxurious period, the kind of painting and sculpture referred to is most highly esteemed by the Christ-god worshippers! Many of the Roman works have been discovered, and serve as models; thus the ancients are imitated in their vicious taste, though condemned as very children of the devil!

With the decay of the darker terrors of the Superstition, the mind, rebounding from asceticism, swung to the other extreme.A rational morality and worship would have preserved a due medium.But with ancient letters revived a love for ancient art; and the indecencies from that source were condoned to the excellency of the work—or pretended to be.The Priests took no care to repress this outburst of voluptuousness; in truth, moulded its nude forms to the embellishment of Temples; and, holding the warm fancies of its devotees, strengthened their influence by a new device.This zeal for the voluptuous in Art and reproduction of Roman types, began by the Roman Pope, spread everywhere. Thus the Superstition itself sanctions this taste, which to us appears so unseemly and immoral.

In Parks and Gardens the English Barbarians are not surpassed. We have no equals in horticulture; but in gardens the English are fine artists, and in parks have caught the true instinct of Nature. When in these, I have felt conscious of a fine civilisation. The lovely parterres of blooming shrubs; the grand vases, rich in brilliant colours of delightful flowers; roses, festooned, trailed in arches over smooth walks; green spaces, where the sunlight lay warm and cheerful; noble avenues of lofty trees; sweet arbours, embowered in blossoms and verdant vines; shady walks, meandering among the trees; groves of evergreens, musical with cascades, gleaming in marble basins; and fountains, ornamented and sculptured in shining stone. Little lakes, where the breezes awoke the sleepy waves and chased them to the shore, and where the aquatic birds of many forms delighted to sport! The whole place eloquent and still in beauty! Here, no force, nor barbaric rudeness, nor worship of brutal strength, nor of hideous forms, nor of lighted altars! Here, the English Barbarian was a civilised man, and here I could love him!

Ah, when shall he, so strong, see his true strength, and know how to use it! Arm no more—teach the other Barbarians the proper use of Force! Dreaming no harm to others, fearing no harm to himself, and using the revenues of his great tribe to render it invincible in virtue—how then invincible in all!

One day one of the High-Caste took me under his Illustrious protection, and conveyed me to his grand House, built of hewn stone in the ancient Roman method. It stood among fine trees, a long and glistening façade [phr-not] of white and ornamental marble. He presented me to his illustrious wife, who graciously saved me from the too great embarrassment of her presence; for, as I shall hereafter explain, the custom of the Barbarians in this respect shocks all our notions. Hanging upon the gilded walls were the costly works of painters—among them naked women, coloured and tinted, in most voluptuous forms, smiling down upon us—upon sculptured pedestals, stood white statues, in rich marbles, of exquisite maidens, nude, and attractive in every graceful attitude and personal charm! All this was surprising, if not pleasing—but when this Lord [Tchou] took me into the gardens and Park, there, indeed, all was calm—the agitation of my spirit subsided!