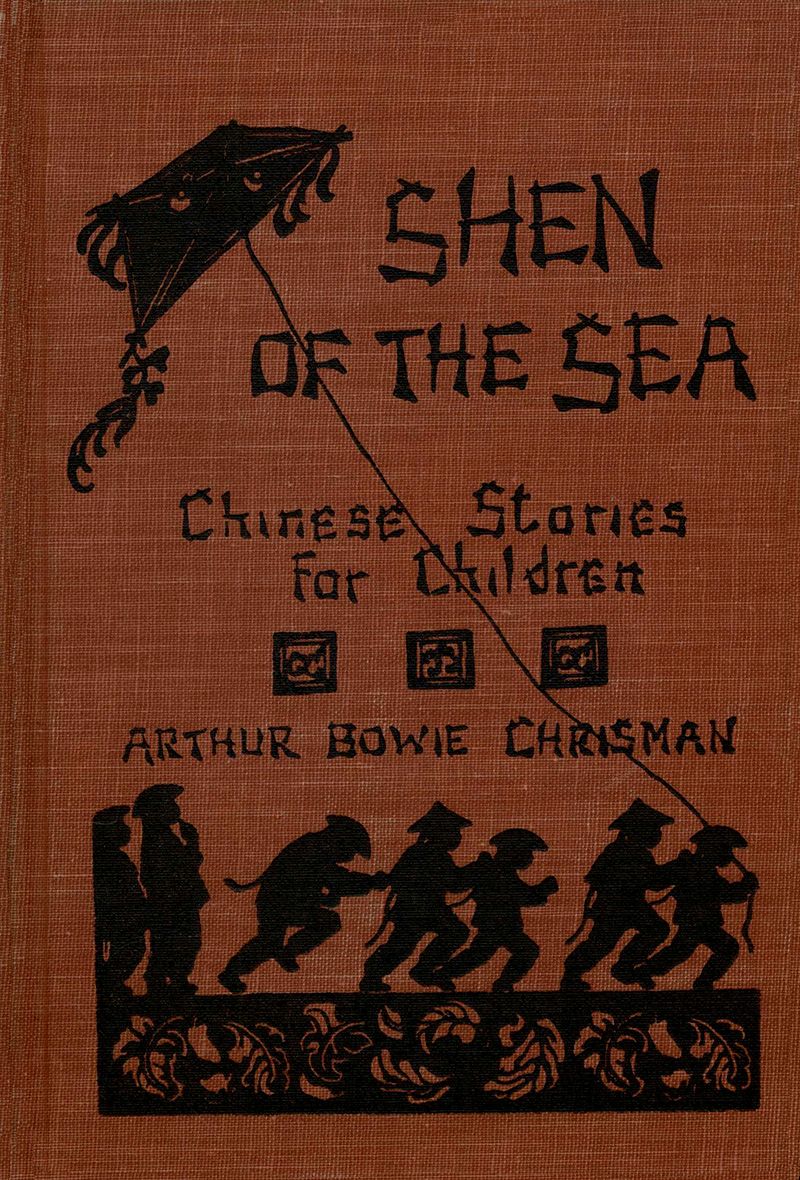

Shen of the Sea: A Book for Children

Play Sample

THAT LAZY AH FUN

Doctor Chu Ping was a good man. He was clever and industrious, and wore his pigtail long. No one knows why he was cursed with such an indolent offspring as that lazy Ah Fun. Perhaps the vice was inherited, with a skip, from Grandfather Chu Ping Fu. They do say in Lao Ya Shen that Grandfather Chu Ping Fu was too lazy even to burn yellow paper on New Year’s Eve, or to beat a copper pan in order to scare away the demons. But no matter about Chu Ping Fu. Let nothing more be said of him. Not Chu Ping Fu, but his graceless grandson is herein to be held up for scorn.

That lazy Ah Fun—for such everyone called him—was nothing if not a sluggard, and so he had been from the cradle.What a shameless creature he was—a snail—a lame snail at that.Dr. Chu Ping sent him with a bamboo tube of brick dust to the house of Chang Chi, where Mrs. Chang lay sick with a fever, and greatly in need of the medicine.And did Ah Fun hasten on his errand?No.A thousand times, no.He dawdled.He took his own, his very own time, that lazy Ah Fun.Poor Mrs. Chang, may she go to a good reward, was three days dead and in her paper coffin before Ah Fun finally arrived with the medicine that was meant to save her.

Now that is but a single instance, and a sad one, of the way in which Ah Fun was wont to dilly and to dally.Here is another illustration.Dr. Chu Ping despatched his son to the pasture land, there to find the cow and fetch her home for milking.Dr. Chu Ping knew the boy’s habit, so he sent him when the sun was highest, at noon, in order that he might get the cow home before darkness came.But Ah Fun went nowhere near the pasture.He sat in the shade, playing the noisy game of “guess fingers” with a comrade in idleness.And when night came, he went to the yard of Low Moo, his next-door neighbor, and drove the Low cow into his own yard.It was so much easier than walking way down to the pasture land for his own cow.

Dr. Chu Ping had milked the cow and the cow had kicked the bucket over before Low Moo came in tears, declaring that he had been greatly wronged and that Ah Fun should be whipped with a bamboo.The other neighbors gathered round, and without exception they said: “That lazy Ah Fun; he is no good.He should be beaten.”But the doctor said that Ah Fun meant no harm—he was merely too tired to go to the pasture, and that some day—(here he thumped vigorously on the bucket, rum tum tum—one always makes a noise to scare the demons, when saying complimentary things)—some day Ah Fun would be a very famous man, and have a monument half a li in height, covered with much carving to tell his praise.

Then the neighbors said “Humph,” and the way they said it was with the corners of their mouths turned down, sneeringly.Clearly, they disbelieved.And one said, “There was never a hyena that didn’t think his own son fairer than the King’s child.”The good doctor laughed heartily at that.He turned to Ah Fun and said (pounding on the bucket): “Ah Fun, treasure of my miserable heart, take you the bucket, and going to the well, fetch us home some water, for there is no milk, the terrible cow having kicked it over.Hence we can have only water with our Evening Rice.And be sure, my chiefest comfort, (rum dum, went the bucket), to rinse the bucket thoroughly, twice at least.”

So Ah Fun took the shui tung (the bucket), and pretended he was going to the well. But the well was a li, a third of a mile distant. The ditch was only a few steps distant. That lazy Ah Fun stopped at the ditch and filled his shui tungHe came home with a bucket half full of green ditch water.And in the water was an old shoe, a discarded shoe, a shoe that someone had thrown away as wornout and utterly useless.Nor had the bucket been rinsed.

But Dr. Chu Ping, instead of scolding Ah Fun, scolded the excellent people of Lao Ya Shen, saying: “This town is getting very very bad.One cannot walk decently and in peace from the well to one’s house, but that some scamp must toss an old shoe in the water bucket.”What a deluded man was that Dr. Chu Ping.

When the spring rains were at their heaviest, Dr. Chu Ping was called from this house to that house to visit the ailing. The rains caused much sickness, and the doctor was out at all hours, no matter how foul the weather. In consequence, he was more often wet than dry, and the wetness worked against his health. One night he came home dripping water from every thread of his garments, and his teeth were chattering, upper against lower. He crawled upon the kang, which is both stove and bed, saying, as well as he could: “Ah Fun, my blessing most cherished, build a fire under the kang. Your so miserable old father has a chill that no doubt will end his wholly useless existence. Build a tremendous fire, Ah Fun, my precious jewel. Ai ya, I am cold and ill.”

Ah Fun tore a few leaves of paper from a medicine book, and inserting them under the kang, struck fire to them. Then he resumed his play. After a while Dr. Chu Ping raised the quilt from his head and hoarsely whispered, “I—I—I am still shivering, Ah—Ah Fun. M—m—more w—w—wood.” Ah Fun looked about, but he saw no firewood. And he was too lazy to go in search. However, the doctor’s gold-crested cane stood in a corner. Well, why not? It was bamboo. It would burn. Into the kang went the cane, and right pleasantly did it crackle. But after a time Dr. Chu Ping again uncovered his head and begged weakly, “M—m—more w—w—wood, Ah—Ah Fun!” Once more Ah Fun looked round the room. There was positively no firewood in sight. However . . . upon a shelf lay half a hundred bamboo cylinders, tubes that contained medicines. In one bamboo was cuttlefish-bone. In another was ko fen (powdered oyster shell). The doctor had used that on old Mrs. Fuh Lung’s rheumatism, with good effect, too. In a third were salt and chieh tzu. A fourth held chen pi and shih hui (orange-peel and lime). The fifth contained chang nao (camphor, and ashes) . . . all good medicines and valuable indeed.

But . . . what did Ah Fun do? He chucked the first bamboo tube into the kang, and the tube crackled as the flames bit through. Presently, he cast in the second tube. Followed the third and fourth. Tube after tube, medicines and all, went into the kang, atop which lay Dr. Chu Ping.

Now it so happened that the fiftieth tube contained huo yao—(the medicine)—and huo yao is made of sulphur, saltpetre, and charcoal—those three, the very three that combine to make Gun Powder—as we call it—nothing less.

Dr. Chu Ping lay upon the kang, all a-twitch with the chill that had worsted him. His son, Ah Fun, threw into the kang a large tube of huo yaoThe fire crackled smartly, eating the tube.Then.“BROOOOMP.”

Oh, that terrible Ah Fun.He has blown up the bed-stove.To say nothing of his honorable father.

It was raining heavily, but just the same Mrs. Low Moo came out and upbraided the doctor unmercifully for coming down in, and utterly havocking, her patch of huang ya tsai (her tender, pretty cabbages). She told him her every thought upon that subject, with such words as “Hun chang tung hsi (Stupid, blundering old thing you).” But Dr. Chu Ping merely gazed sheepishly at the destroyed cabbages, and at the hole in the room through which he had been blasted, and murmured, “Kai tan (Ah me, what a pity).”

And again came the other neighbors, the very kind people who loved Dr. Chu Ping and wished to help him in his troubles. These well-wishing neighbors came and said: “Beyond a doubt, that boy is to blame. Honorable doctor, why do you not break many stout bamboos upon the back of that boy—that lazy, good-for-nothing Ah Fun? He will be the disgrace of, and the death of you yet.” But Dr. Chu Ping rubbed his shoulder and said: “What? Beat Ah Fun? Why he is a good boy and a comfort. He just built me an excellent fire in the kang.”

Then the doctor limped into his house and awoke Ah Fun, asked him what had happened. Ah Fun, though he was bad—goodness knows, terribly bad—yet was truthful. Reluctantly, we must give him credit for that. He told of all that had happened: how he placed tube after tube in the kang—being unable to discover any firewood—and how the last tube had exploded, hurling his father through the roof.

Dr. Chu Ping wrinkled his brow till it was all hills and hollows. He pulled his long and neatly braided hair in a highly meditative manner. He felt first his right shoulder, then his left shoulder. He rolled his eyes upward to the limit of their travel. He gazed at the hole in the roof, where still fluttered a fragment of clothing on a jagged edge. He rolled his eyes downward and scrutinized the ruined kangHe felt of his two ears that still reverberated with the enormous explosion.Then he spoke.“My son,” said he, “it strikes me that we are on the verge of a great discovery.One of those medicines—though gracious knows which one—seems to be more than a medicine.It is good for something else—though dear knows what.Perhaps to grow wings, so that men may fly.It certainly enabled me to fly.We must make more medicines, and experiment.”

The next day Dr. Chu Ping opened his book of instructions for the compounding of medicines—a book which he himself had written.Beginning at the very beginning—which, of course, was on the last page, good Dr. Chu studied the first formula.“Red pepper, and alum, and toad claws,” so he read.The three ingredients were found and mixed in the specified proportions.The mixture was poured into a bamboo tube and the tube was placed in a fire.For an hour Dr. Chu Ping stirred the fire and fanned it into furious blazing.Nothing but much heat and much smoke resulted.There was no noise and no flying.Clearly, the combination of pepper, alum, and toad claws was quite worthless—except in the treatment of scarlet fever, for which it is intended.The doctor made a careful writing of the experiment and turned another page.

Next came oyster shell and ginseng. Worthless that, also. Shark fins and turmeric. Dr. Chu Ping marked that likewise worthless. So the experimenting continued, day after day. It took a great deal of time. The doctor was a most thorough man, as well as brilliant. One couldn’t find a more thorough or brilliant in all Kiang Su, or Kiang Si, or even in Kuang Si. Methodically he tried his medicines in the fire—by one and one he tried them—and thus he came to the mixture huo yao, which, to repeat, is sulphur, and saltpetre, and charcoal, and which the Fan Kwei, or Foreign Devils, with their white faces call Gun Powder. Dr. Chu Ping placed a long tube of huo yao in the fire. He leaned over it, fanning vigorously. For a moment the tube lay on the coals, sizzling and swelling, seeming to gather its breath for a supreme effort. . . . Zzzzzzz. . . . Zeeeee. . . . BROOOOMP.

And up went Dr. Chu Ping.

Now it so chanced that a moment before the explosion, old man Low Moo was milking his cow. A moment after the explosion, he was not milking his cow. He was running for dear life in a northerly direction. His cow was running for dear life in a southerly direction. And Dr. Chu Ping sprawled upon the flattened bucket and the smashed stool, where he had fallen.

The doctor came to in five minutes.Old Mr. Low Moo came back in half an hour.The cow has never since been seen.It is doubtful if she will ever return.

No sooner did Dr. Chu Ping revive than he hobbled into the house, where Ah Fun sat calmly playing with a pan pu tao, a little toy man who has round feet, and always regains an upright position, no matter how often he is knocked over. “What happened, my father?” asked Ah Fun. Dr. Chu Ping beamed upon him. “Ah Fun, my pearl, my jade, my orange tree, it is discovered. Huo yao is the great medicine. And it is good for scaring demons. Old man Low Moo, as everyone knows, is possessed of a demon—and he was frightened horribly. And his unkind cow, which is guided by at least four and twenty demons, has been frightened completely out of the country. There can be no doubt—huo yao is a frightener of demons. And, you and I are the discoverers. Oh, my precious one, we shall be famous. A thousand thousand years from now men will still use huo yao to scare the demons.”

And that was a very good prediction. Huo yao is still placed in tubes, little paper tubes, and the fuses are lighted, and “Sput,” “Sput.” The firecrackers explode and a thousand demons tremble and flee, reviling the names of Ah Fun and Dr. Chu Ping, who invented Gun Powder.

THE MOON MAIDEN

King Chan Ko was more than a monarch. He was one of the best soothsayers in all the discovered world, having studied under no less a master than the famous Chai Lang. Even the most sceptical, then, will admit that Chan Ko as a geomancer must have stood far above the average. Chai Lang was particular in the selection of his pupils.

Once each week, at its beginning, His Majesty was accustomed to cast the signs, so that he might know what to expect.Thus, if rain was due on a Wednesday he was forewarned, and fore-umbrellaed.And if war was predicted for Friday, he was forearmed and ready to give two blows for one.He knew of the third flood a whole week before it happened, and, you may be sure, had a palatial boat provisioned and ready—laden with rice and musical instruments—a good three days before the waters came.

Rather unexpectedly, it became imperative for King Chan Ko to take horse on an urgent journey.Despite the call for great haste, he refused to make one step before casting the signs—though to do so made necessary an hour’s labor.On his plane Chan Ko scribed the three circles with their bisecting lines.He drew the sun, moon, and stars in their relative places, gazed for a moment .and groaned.“Ai yu,” and “Hai ya.”

Well might he groan. There was no error in the work. No other reading was possible. Upon the following night a dragon would swoop down from the moon and carry off the Princess Yun Chi. That was the reading, and there could be no doubting its truth. It may be imagined that gray hairs made quick appearance in the monarch’s beard. His journey was highly necessary. No postponement could be arranged. Yet, the Princess Yun Chi, his daughter, was well beloved and not to be given up so long as sword had temper and javelin was sound of shaft. But—who was to wield sword, who to thrust javelin? Who indeed? Who if not the four score and ten valiant young princes of the realm, who even then deplored a dearth of daring deeds to be performed. No sooner the thought, than King Chan Ko summoned the princes into audience. Briefly he described the peril that threatened—told of the dragon’s cunning, of his strength that increased with every blow, given or received. Not a pleasant picture King Chan Ko drew—at first. But when in conclusion he stated the reward, every prince in the chamber drew sword, and wished that the dragon might come forthwith. For, said Chan Ko, “If all of you together slay the loong, then if she so pleases, the princess may make her choice of you. But if any prince, unaided, slays the loong, then I say to you that such victorious prince and none other shall wed the Princess Yun Chi.”

There was such a clanking of armor that the magpies clustering the palace roof made off on wing.There was such a testing of newly strung bows that the sky rained arrows for a whole day.

Prince Ting Tsun, as comely warrior youth as ever twirled sharp steel, took to himself a notion that his sword alone must blood the dragon. He can hardly be censured. Anyone is likely to be greedy when a royal princess is in danger, and her hand awaits an heroic defender. But Ting Tsun, with his bravery mixed sagacity. To himself he reasoned thus: “Suppose I do succeed in killing the moon dragon? Will his infuriated brothers not come seeking vengeance? Without doubt they will. My only hope is to slay them all—now—and their ruler with them. Then the danger will be removed forever, and I can eat rice in comfort, without the need of a sword on the table. I must kill all of the moon loongs.”

With such an ambitious plan in mind, Prince Ting Tsun visited a sewing woman and had her make him a cloak precisely like that worn by the Princess Yun Chi.He shaved his promising beard and put whiting upon his cheeks, painted his eyebrows, and practiced a willowy walk.All in all he made a fairish pretty maiden, and quite deceiving to the eye.

When the sun had snuggled down behind the mountains, Prince Ting Tsun walked in the palace gardens, taking those paths most favored by the princess.He fondled the delicate wistaria.He touched his face to the wide expanded roses.Beneath the purple flowered paulownia he paused in rapture.By look and action he was a maiden, taking her pleasure in the flowers.

Out of the calm evening air came a mighty and horrendous whistling roar. No need to tell the prince its cause. In his early days he had heard silly nurses attempt such a whistling, trying to frighten him into being “a good boy. If you don’t, the loong will get you.” He had laughed at the affronted nurses. But now . . . his face was crinkled with grim lines, serious lines that spelled determination. Not a trace of laughter there. The whistling changed to a hissing. The air became noxious with hot breath. Four tremendous, padded talons enfolded Prince Ting Tsun. A scream of terror. A whanging of wings that lifted. . . . Gone. . . . Vanished.

A scream of terror?No, that is not true.It was a scream of mock terror.Can you think the prince was frightened?Prince Ting Tsun?He screamed merely to make his deception doubly sure.The prince to casual gaze was a maiden, and maidens are supposed to scream when snapped up by a dragon.Small blame to them for that.

Up.Higher.Swifter.Up through the uncharted, the star-littered spaces, swept Prince Ting Tsun, borne by the dragon.The wind shrieked past him.Higher, still higher.The little stars twinkled above.Higher.The little stars twinkled below.The air grew thin and cold.Prince Ting grew faint, for his breathing was of no consequence.There was no air to breathe.There was nothing but space and star-dust.

The loong’s mouth went wide in a whinnying whistle. From close by came an answer. The prince opened his eyes. He saw a tapering streak of flame. On earth he would have named it “comet.” But stretching his eyes wider, he perceived that it was merely another dragon, its fiery breath trailing, far spread.

Other loongs appeared; Ting Tsun imagined that he must be approaching their lair. He prayed that his arm might be strong.

With another scream the dragon folded his wings and dropped lightly upon a silvery plain.The journey was done—the moon under foot.

The dragon King ruled in a subterranean palace.The entrance was merely a shining smooth hole, but the interior was luxury itself, with brocaded tapestries and jade floorings and translucent moonstone ceilings.In the throne room knelt Ting Tsun before the King—for he still played the part of a maiden.He knelt as if seeking mercy.

“Her beauty is not what I expected,” growled the King.“Take her away.Perhaps another day she will seem fairer.Let her food be sesame and coriander seeds.Ugh.What a clumsy walk.”

Prince Ting Tsun sat on a couch, turning in his mind a plan by which to vanquish his captors.The stillness was dissolved by a music of moving silks.A smiling damsel bowed before His Highness.

“Oh, I am glad to see that you do not weep like the others. Are you a princess from the earth, or from chin hsing (venus)?”

“From the earth,” replied Ting Tsun, but he forgot to gentle his voice.The Moon Maiden shrank back.

“You are not a princess,” she accused.

“No, I am not a princess. These garments are a deceit. I was Prince Ting Tsun, when upon the earth. Now, I am Chang Pan—your slave.”

The Moon Maiden was quickly reassured and entered into talk with Ting Tsun, or humble Chang Pan, as he then called himself. She told the prince that she had lived with her parents on the far side of the moon—until the dragons came. Now she had no parents. And when the feast season of Brightest Light arrived the dragon King (Chao Ya, his name) would make her his bride. She knew the number of dragons—twenty-eight, one for each night in the month, and there was never more than one home at a given time. They could be slain only with the dragon King’s sword—a weapon that could slay the King himself. But—and the hopes of Prince Ting fell as she spoke—the King always kept the sword fastened at his waist. Yes, the loong King sometimes slept, but never more than once a day, and never for more than a few minutes. When? Just as the moon went down.

So Ting Tsun in his spotless maiden garb came upon the King asleep, and snatching up the monarch’s sword, awoke him and slew him.The blade had not yet done its sweep when it cleft the skull of a dragon who should have been guarding his King from harm.

The prince rejoiced at his success, howbeit rather modestly.His task had but started.There was many a chance for disaster.Death might lurk in a faltering blow, a lagging step, a momentary closing of the eyes.

By day the prince slept. By night he kept his post at the palace entrance. As each loong came crawling into his lair Prince Ting Tsun reached its heart with the dragon King’s sword. One thrust for each loongOne thrust each night, until a month had passed.In such manner His Valiant Highness destroyed the whole vile brood.His plans had carried through to triumph.Now he was free to return home and claim for his own the Princess Yun Chi.And a happy day it would be.He was happy now .oh, extremely happy.Why shouldn’t he be happy? .the prince argued stoutly with himself.Yet his argument was not convincing.He would be compelled to leave the Moon Maiden.So his reasoning was hollow.He was not happy.He was sorrowful.He had grown fond of the Other World Princess.

But he must return to his own country.King Chan Ko had promised his daughter to whosoever should slay the dragon.In taking up battle, Prince Ting had given agreement to the terms. He was betrothed to the Princess Yun Chi.

The Moon Maiden was asleep when Prince Ting went to say good-bye.He would not wake her.He would go at once—after a last sad look.The sleeping princess stirred in her sleep and murmured.For another instant the royal youth paused.He heard his name murmured.He heard more—enough to amaze him, to weaken his will almost to the changing point.A moment more of listening, and Prince Ting Tsun must inevitably have remained upon the moon.But he would hear no more.He rushed from the palace, ashamed of his weakness, yet thrilled with pride.

The moon hung low above the eastern ocean when Ting Tsun made his fearsome leap.He descended in the cushioning waters, and so took no hurt.Fortune was with him in that leap.A vessel, manned by venturesome explorers, chanced upon him.Otherwise, the spot where he fell must have been his grave, for ships are years apart in that faraway region.The sailors drew him aboard their junk and treated him with every respect.It was quite clear in their minds that he must be a god—certainly, he could be nothing less than a great magician.

When the ship touched at Ma Kao, Prince Ting Tsun was the first to step ashore.He found the city celebrating, burning much colored paper to the ruler of Married Happiness, feasting and making music.Accosting a stranger, he asked the cause of such jubilation, explaining that he had only that moment arrived from a far country.

The stranger answered: “We celebrate a marriage, your grace; Prince Yen has taken the fairest bride in all the world.From what country do you come?”

“Whom did Prince Yen marry?”asked Ting Tsun.

“Why, the Princess Yun Chi, of course.What country did you say?”

“Indeed?”exclaimed the prince.“And I came from the moon.”Leaving the fellow with eyes popped and mouth agape, he hastened on.He was compelled to hasten.His feet would keep step with his tumultuous heart.So the Princess Yun Chi was married.King Chan Ko had broken his word.Far better if Prince Ting had remained upon the moon.Upon the moon was one who.

Pausing only for momentary snatches of sleep, Prince Ting journeyed the straightest road to Kwen Lun Mountain.On this mountain lived, and lives, the friendly mother demon, Si Wang, a magician of great power.To her Prince Ting gave his necessary oath, and in exchange received his desire—wings feathered from the pinions of a Phoenix.

The way is long.The way is steep.But hearts must be served.With wings unfaltering, Prince Ting Tsun cleaves the sky.Between the earth and the lighted moon his shadow may be seen—nearing the silvered plain, and the palace, and the princess.Prince Ting Tsun returning to his Maiden of the Moon.

AH TCHA THE SLEEPER

Years ago, in southern China, lived a boy, Ah Tcha by name. Ah Tcha was an orphan, but not according to rule. A most peculiar orphan was he. It is usual for orphans to be very, very poor. That is the world-wide custom. Ah Tcha, on the contrary, was quite wealthy. He owned seven farms, with seven times seven horses to draw the plow. He owned seven mills, with plenty of breezes to spin them. Furthermore, he owned seven thousand pieces of gold, and a fine white cat.

The farms of Ah Tcha were fertile, were wide.His horses were brisk in the furrow.His mills never lacked for grain, nor wanted for wind.And his gold was good sharp gold, with not so much as a trace of copper.Surely, few orphans have been better provided for than the youth named Ah Tcha.And what a busy person was this Ah Tcha.His bed was always cold when the sun arose.Early in the morning he went from field to field, from mill to mill, urging on the people who worked for him.The setting sun always found him on his feet, hastening from here to there, persuading his laborers to more gainful efforts.And the moon of midnight often discovered him pushing up and down the little teak-wood balls of a counting board, or else threading cash, placing coins upon a string.Eight farms, nine farms he owned, and more stout horses.Ten mills, eleven, another white cat.It was Ah Tcha’s ambition to become the richest person in the world.

They who worked for the wealthy orphan were inclined now and then to grumble.Their pay was not beggarly, but how they did toil to earn that pay which was not beggarly.It was go, and go, and go.Said the ancient woman Nu Wu, who worked with a rake in the field: “Our master drives us as if he were a fox and we were hares in the open.Round the field and round and round, hurry, always hurry.”Said Hu Shu, her husband, who bound the grain into sheaves: “Not hares, but horses.We are driven like the horses of Lung Kuan, who ..”It’s a long story.

But Ah Tcha, approaching the murmurers, said, “Pray be so good as to hurry, most excellent Nu Wu, for the clouds gather blackly, with thunder.”And to the scowling husband he said, “Speed your work, I beg you, honorable Hu Shu, for the grain must be under shelter before the smoke of Evening Rice ascends.”

When Ah Tcha had eaten his Evening Rice, he took lantern and entered the largest of his mills.A scampering rat drew his attention to the floor.There he beheld no less than a score of rats, some gazing at him as if undecided whether to flee or continue the feast, others gnawing—and who are you, nibbling and caring not?And only a few short whisker-lengths away sat an enormous cat, sleeping the sleep of a mossy stone.The cat was black in color, black as a crow’s wing dipped in pitch, upon a night of inky darkness.That describes her coat.Her face was somewhat more black.Ah Tcha had never before seen her.She was not his cat.But his or not, he thought it a trifle unreasonable of her to sleep, while the rats held high carnival.The rats romped between her paws.Still she slept.It angered Ah Tcha.The lantern rays fell on her eyes.Still she slept.Ah Tcha grew more and more provoked.He decided then and there to teach the cat that his mill was no place for sleepy heads.

Accordingly, he seized an empty grain sack and hurled it with such exact aim that the cat was sent heels over head.“There, old Crouch-by-the-hole,” said Ah Tcha in a tone of wrath.“Remember your paining ear, and be more vigilant.”But the cat had no sooner regained her feet than she changed into .Nu Wu .changed into Nu Wu, the old woman who worked in the fields .a witch.What business she had in the mill is a puzzle.However, it is undoubtedly true that mills hold grain, and grain is worth money.And that may be an explanation.Her sleepiness is no puzzle at all.No wonder she was sleepy, after working so hard in the field, the day’s length through.

The anger of Nu Wu was fierce and instant.She wagged a crooked finger at Ah Tcha, screeching: “Oh, you cruel money-grubber.Because you fear the rats will eat a pennyworth of grain you must beat me with bludgeons.You make me work like a slave all day—and wish me to work all night.You beat me and disturb my slumber.Very well, since you will not let me sleep, I shall cause you to slumber eleven hours out of every dozen.Close your eyes.”She swept her wrinkled hand across Ah Tcha’s face.Again taking the form of a cat, she bounded downstairs.

She had scarce reached the third step descending when Ah Tcha felt a compelling desire for sleep.It was as if he had taken gum of the white poppy flower, as if he had tasted honey of the gray moon blossom.Eyes half closed, he stumbled into a grain bin.His knees doubled beneath him.Down he went, curled like a dormouse.Like a dormouse he slumbered.

From that hour began a change in Ah Tcha’s fortune. The spell gripped him fast. Nine-tenths of his time was spent in sleep. Unable to watch over his laborers, they worked when they pleased, which was seldom. They idled when so inclined—and that was often, and long. Furthermore, they stole in a manner most shameful. Ah Tcha’s mills became empty of grain. His fields lost their fertility. His horses disappeared—strayed, so it was said. Worse yet, the unfortunate fellow was summoned to a magistrate’s yamen, there to defend himself in a lawsuit.A neighbor declared that Ah Tcha’s huge black cat had devoured many chickens.There were witnesses who swore to the deed.They were sure, one and all, that Ah Tcha’s black cat was the cat at fault.Ah Tcha was sleeping too soundly to deny that the cat was his.So the magistrate could do nothing less than make the cat’s owner pay damages, with all costs of the lawsuit.

Thereafter, trials at court were a daily occurrence.A second neighbor said that Ah Tcha’s black cat had stolen a flock of sheep.Another complained that the cat had thieved from him a herd of fattened bullocks.Worse and worse grew the charges.And no matter how absurd, Ah Tcha, sleeping in the prisoner’s cage, always lost and had to pay damages.His money soon passed into other hands.His mills were taken from him.His farms went to pay for the lawsuits.Of all his wide lands, there remained only one little acre—and it was grown up in worthless bushes.Of all his goodly buildings, there was left one little hut, where the boy spent most of his time, in witch-imposed slumber.

Now, near by in the mountain of Huge Rocks Piled, lived a greatly ferocious loong, or, as foreigners would say, a dragon. This immense beast, from tip of forked tongue to the end of his shadow, was far longer than a barn. With the exception of length, he was much the same as any other loong. His head was shaped like that of a camel. His horns were deer horns. He had bulging rabbit eyes, a snake neck. Upon his many ponderous feet were tiger claws, and the feet were shaped very like sofa cushions. He had walrus whiskers, and a breath of red-and-blue flame. His voice was like the sound of a hundred brass kettles pounded. Black fish scales covered his body, black feathers grew upon his limbs. Because of his color he was sometimes called Oo Loong. From that it would seem that Oo means neither white nor pink.

The black loong was not regarded with any great esteem. His habit of eating a man—two men if they were little—every day made him rather unpopular. Fortunately, he prowled only at night. Those folk who went to bed decently at nine o’clock had nothing to fear. Those who rambled well along toward midnight, often disappeared with a sudden and complete thoroughness.

As every one knows, cats are much given to night skulking. The witch cat, Nu Wu, was no exception. Midnight often found her miles afield. On such a midnight, when she was roving in the form of a hag, what should approach but the black dragon. Instantly the loong scented prey, and instantly he made for the old witch.

There followed such a chase as never was before on land or sea. Up hill and down dale, by stream and wood and fallow, the cat woman flew and the dragon coursed after. The witch soon failed of breath. She panted. She wheezed. She stumbled on a bramble and a claw slashed through her garments. Too close for comfort. The harried witch changed shape to a cat, and bounded off afresh, half a li at every leap. The loong increased his pace and soon was close behind, gaining. For a most peculiar fact about the loong is that the more he runs the easier his breath comes, and the swifter grows his speed. Hence, it is not surprising that his fiery breath was presently singeing the witch cat’s back.

In a twinkling the cat altered form once more, and as an old hag scuttled across a turnip field. She was merely an ordinarily powerful witch. She possessed only the two forms—cat and hag. Nor did she have a gift of magic to baffle or cripple the hungry black loongNevertheless, the witch was not despairing.At the edge of the turnip field lay Ah Tcha’s miserable patch of thick bushes.So thick were the bushes as to be almost a wall against the hag’s passage.As a hag, she could have no hope of entering such a thicket.But as a cat, she could race through without hindrance.And the dragon would be sadly bothered in following.Scheming thus, the witch dashed under the bushes—a cat once more.

Ah Tcha was roused from slumber by the most outrageous noise that had ever assailed his ears.There was such a snapping of bushes, such an awful bellowed screeching that even the dead of a century must have heard.The usually sound-sleeping Ah Tcha was awakened at the outset.He soon realized how matters stood—or ran.Luckily, he had learned of the only reliable method for frightening off the dragon.He opened his door and hurled a red, a green, and a yellow firecracker in the monster’s path.

In through his barely opened door the witch cat dragged her exhausted self.“I don’t see why you couldn’t open the door sooner,” she scolded, changing into a hag.“I circled the hut three times before you had the gumption to let me in.”

“I am very sorry, good mother.I was asleep.”From Ah Tcha.

“Well, don’t be so sleepy again,” scowled the witch, “or I’ll make you suffer.Get me food and drink.”

“Again, honored lady, I am sorry.So poor am I that I have only water for drink.My food is the leaves and roots of bushes.”

“No matter.Get what you have—and quickly.”

Ah Tcha reached outside the door and stripped a handful of leaves from a bush.He plunged the leaves into a kettle of hot water and signified that the meal was prepared.Then he lay down to doze, for he had been awake fully half a dozen minutes and the desire to sleep was returning stronger every moment.

The witch soon supped and departed, without leaving so much as half a “Thank you.”When Ah Tcha awoke again, his visitor was gone.The poor boy flung another handful of leaves into his kettle and drank quickly.He had good reason for haste.Several times he had fallen asleep with the cup at his lips—a most unpleasant situation, and scalding.Having taken several sips, Ah Tcha stretched him out for a resumption of his slumber.Five minutes passed .ten minutes .fifteen.Still his eyes failed to close.He took a few more sips from the cup and felt more awake than ever.

“I do believe,” said Ah Tcha, “that she has thanked me by bewitching my bushes.She has charmed the leaves to drive away my sleepiness.”

And so she had.Whenever Ah Tcha felt tired and sleepy—and at first that was often—he had only to drink of the bewitched leaves.At once his drowsiness departed.His neighbors soon learned of the bushes that banished sleep.They came to drink of the magic brew.There grew such a demand that Ah Tcha decided to set a price on the leaves.Still the demand continued.More bushes were planted.Money came.

Throughout the province people called for “the drink of Ah Tcha.”In time they shortened it by asking for “Ah Tcha’s drink,” then for “Tcha’s drink,” and finally for “Tcha.”

And that is its name at present, “Tcha,” or “Tay,” or “Tea,” as some call it.And one kind of Tea is still called “Oo Loong”—“Black Dragon.”

I WISH IT WOULD RAIN

It rains and rains in Kiang Sing. And then it rains some more. No sooner is one cloud past then another comes treading on its heels. By day and by night the raindrops patter, and ko tzu from his lily pad croaks “More rain. More rain.” Old men going to bed wear their wei li (rain hats), instead of tasseled nightcaps. Many young people have only a hazy idea as to what the word “sun” means. Pour and beat and drizzle, drizzle and drive with the gale. And that is Kiang Sing.

Three reasons are given by the people of Kiang Sing for their extremely weepy climate. Some say that the shen Yu Shih, who lords it over the clouds, lives near by on the Daylight Mountain. Others are firm in their declaration that Moo Yee, the mighty archer, and a naughty fellow withal, shot the sky above Kiang Sing full of arrow holes. Naturally, a sky full of arrow holes is bound to leak. There are still others, and very learned folk among them, who declare that Mei Li weeping for her lost hero, Wei Sheng, is responsible for the torrents. Dear only knows which is the correct theory. It may be that all three are to blame. The only certainty is that Kiang Sing has a very heavy rainfall, and that Tiao Fu lived there and learned to love wet weather. . . . To love it? She hated it.

Tiao Fu was a very pretty maiden—no gainsaying that. She had the most wonderful black long hair in all Kiang Sing. But beauty was her one and only possession. She had no skill with the needle, whether to sew or embroider. Her cooking was more than a disgrace. When her fingers touched the pi pa, that usually sweet-toned instrument gave out a demon’s wail. She could not even smooth a quilt on the kangThe beds were all hills and hollows.How could she make beds when her hair needed burnishing?She scarce knew which end of a broom was meant for the floor.How could she sweep when her hair required glossing?New matting would cover the floor’s disarray.Tiao Fu smoothed her hair and dreamed of the time when she would marry a rich mandarin and be carried in glory away from Kiang Sing and its terrible rains.The hateful rains of Kiang Sing.

No wonder her father, Ching Chi, became so poverty-stricken. Gradually his fortune slipped away until his only property was the large and poorly furnished, extremely ill-kept house in which he lived. Even so, this house when viewed from the street appeared superior to its fellows. It was the handsomest and most considerable yamen in Pin Jen Village.

The size and appearance of the yamen accounts for what happened. One fiendish night, in a mighty drumming of rain, there came a more noisy drumming of maces upon Ching Chi’s door. “Open, in the King’s name,” commanded voices outside. Forthwith Ching Chi flung open the door. He beheld runners dressed in the royal livery, and in their hands the gold-banded staves of their authority. “Prepare to receive and entertain the illustrious person of Ho Chu the King. His Most Gracious Majesty will arrive sha shih chien (within a slight shower’s time). Therefore prepare. It is a command.”

Far from entertaining royalty, old Ching Chi had never so much as glimpsed a King. Heart and knees failed him utterly. He could only grovel upon the floor and mutter weakly of his unworthiness. Tiao Fu, however, was not so deeply affected. A King? Let him enter. Say what you please, kings are mortal men. No food in the house? Ya ya pei (Pish pooh). And the tradesmen refused all credit? What of it? No tradesman in his senses would refuse a bargain. And what would the bargain be?

Tiao Fu snatched up her little-used embroidery scissors. Snip. Snip. Snip. Down fell a cataract of her long black hair. Snip. Snip. Again and again. The hair that was her vanity lay upon the floor. Her lustrous hair—sacrificed—to make a feast for the King. Hastily donning her father’s wei li, she dashed from the house.There was no trouble in making a bargain.The tradesman’s first offer was almost within reason and Tiao Fu had no time to wrangle.She bartered her hair for cooked fowls and rice and all that goes to make a dinner.

King Ho Chu arrived betimes.The weather despite, he was in good spirit.He was such a considerate and jolly monarch that he soon had old Ching Chi at perfect ease.The dinner was a delight to eye and tongue.It was the best meal that had been served in Ching Chi’s home for many a moon.And Tiao Fu’s hair bought it.

After the cups were turned down, King Ho Chu inquired about his horse. To reiterate, he was a most considerate sovereign. He wished to feel sure that his steed was housed from the rain, and shoulder deep in a well-filled manger. Ching Chi beamingly affirmed that the horse had been provided for, lavishly. What else could he say? However, he would make sure, doubly sure, by going to the stable again.

Of course, the poor horse had not a mouthful.There was not so much as a wisp of hay in the stable, not so much as a bean, or a stalk.Ching Chi was sunken in weepy despair when the girl Tiao Fu appeared with a matting from her bedroom floor.It was a newly made matting, of bright clean straw.Tiao Fu tore it into shreds and filled the manger heaping.Thus was the King’s horse supplied with food—food none too nourishing, but food nevertheless.

There are many channels through which kings may receive news and rumors and tittle-tattle.What with the secret police and the mandarins who wish to gain favor and the—the sparrows—the royal palace keeps well informed.(Besides, one historian takes several pages to prove that Tiao Fu possessed a tongue and could use it to her advantage.)However that may be, the news spread.Within a day King Ho Chu learned how the maid Tiao Fu had provided a feast at the expense of her hair.He learned all about the shredded matting, and his laughter shook the throne.He bestowed more than a passing thought upon Tiao Fu of the quaintly bobbed locks—the maiden a thousand years ahead of her time.And having thought—he acted.He said to the Minister of Domestic Affairs, “Prepare a room with hangings of orange-colored silk.”To the Minister of the Treasury he said, “Bestow a dozen or so bars of gold upon the mandarin Ching Chi.”The Minister of Matrimony received his command, “Arrange me a wedding with the maid Tiao Fu, of Kiang Sing.”So all things were arranged and came to pass.

King Ho Chu was well pleased.Old Ching Chi was the happiest man living.The maid Tiao Fu was quite content—for a space.She had gowns of gorgeousness undreamed.She had slaves to kneel and knock their heads whenever she beckoned.She had priceless jewels and food of the rarest.Incidentally, she had in the King a doting husband.She had everything—everything—except rain.

Is it not hard to believe that Tiao Fu grew homesick for the rains of Kiang Sing?It is a strain upon belief, yet it is true, indubitably.Tiao Fu longed for the rains of her drenched and soggy much be-drizzled Kiang Sing.Did the King present her with a new necklace—she threw it petulantly away, exclaiming that she wanted rain—“Oh, I wish it would rain,” said Tiao Fu.“Why don’t you make it rain?”“Then I will,” said the King.He installed a myriad high-spouting fountains, at no slight drain to the treasury.“Are you pleased, my beauteous Tiao Fu?”“No,” fretfully.“It is not like the rains of Kiang Sing.Why are the trees not green?The trees are bare and brown.Oh, I wish it would rain—a green-bringing rain.”

The trees might very well be bare and brown. Winter’s greedy fingers had stripped them thoroughly. King Ho Chu gazed at the barren limbs for a lengthy period before his mind hit upon a scheme for bringing back the green. At length he summoned the royal tailor and to him said: “Take many bales of green-colored silk and cut leaf-shaped pieces. Dip the pieces in wax; then sew them upon those bare branches. And use such artistry that no eye can discover they are not true leaves. Tsu po (be quick).” The cheng i (make clothes) hastily employed all the city’s master workmen, some cutting and many sewing. Overnight the trees took on a color. Indeed, the tailor went beyond his orders, for on the peach trees he sewed lovely pink blossoms. And some blossoms he tacked to the ground—as if in their ripeness they had fallen.

For a few days Tiao Fu was in somewhat better humor.Once she actually smiled.But all too soon those few days were over and her crossness returned.“What now, my pearl of southern seas?”said the King.“Have the leaves lost their freshness?Do they no longer please?”“Oh [pout], it isn’t the leaves.They are quite homelike.It’s the wind that I miss.I long to hear the shrieking wind of Kiang Sing, hurling its rain against my lattice.Oh, I wish it would rain.”

Poor King Ho Chu was hard put.Wind?Wind? .By the uprooted pine tree of Mount Tai, how was he to produce the wind.A good half hour—sixty minutes in that land—passed before he had an inspiration.Again he called for the royal tailor.“Procure,” he told the tailor, “many bales of the stoutest silk.Then place some of your brawniest men outside yonder lattice, and have them rip the silk, tear it into strips—with all the noise possible.”With which King Ho Chu entered the treasury to see how his gold was dwindling.

Huge-armed stalwarts stood outside Tiao Fu’s window.Their hands clutched the woven silk.A pull.“Sh-r-r-r-r-iek.Pull.Sh-r-r-r-iek.”For two days the brow of Tiao Fu was smooth and untroubled.She actually spoke kindly to the King.He, poor soul, didn’t hear it.He was too busy wondering what the next task would be, and how expensive.

Scarcely a hundred bales of silk had been torn when Tiao Fu hurled her crown across the room and began to weep. “My dear, what’s the trouble? What is the trouble?” questioned Ho Chu. “Is the wind too violent?” “Oh, no. The wind is natural enough, and it pleases me. I miss—oh, how I do miss the rumbling thunder of Kiang Sing, and the fall of lightning-shattered trees. I miss them and oh, I wish it would rain—real rain.” The tears fell faster with each word.

Now King Ho Chu had a tremendous army encamped on the palace grounds.He summoned General Chang and explained matters—with an order.No sooner ordered than accomplished.The soldiers in their heaviest shoes marched ponderously beneath the latticed window.“Boom.Boom.Bru-u-u-um.Bru-u-u-um.Bru-u-u-u-ump.”And how do you like our thunder?Little drums and great, they rattled and roared.“Rap-p-p.Boom.Boom..”In endless line the soldiers marched.One day.Two days.Three days.Four.Some of them slept while the others marched.Boom.Boom.Boom.The sun on their spears blazed and flickered—the lightning.By night there were flashing fires.

It is gratifying to relate that Tiao Fu was moderately pleased.Her appetite returned and the tears were withheld.She spoke to the King with kindness—several times.All might have gone well had not some malcontents down Kan Su way started a rebellion.Off went the army—General Chang waving his sword, and the smallest drummer boy thumping with glee.That was at midnight.

The dawn was at its breaking when beacons along the line of march flared up.“Halt” was the signal.The army halted.Again the beacons flared.They spelled the word “Return.”

Tiao Fu was not so well.She longed for the roll of the drums to remind her of Kiang Sing’s thunder.What could the poor King do but recall his army?The rebellion in Kan Su continued merrily.And General Chang, who was an old-time soldier, expressed his opinion—rather explosively—to a sympathetic staff officer.But never mind that.Let the drums sound.

When the rebellion spread to Kan Si, the King felt that things had gone quite far enough.It was time to teach those rebels a lesson.Away went the army again.

A whole day passed and no return order was signaled.Night came and the army tramped onward.A pillar of flame shot up from a hilltop.It was a beacon.“Return,” said the beacon.“Not I,” said General Chang; “I’ve had enough of the Queen’s whims. Besides, it’s raining right now.Forward.March.”

The army entered Kan Su and there encountered the rebels.It is better that the fight go undescribed.Here suffice it to say that if so much as one rebel escaped, he took pains to keep the fact secret.There is no mention of him in the books.

General Chang was jubilant.Surely the King would be highly pleased.The King—good gracious—King Ho Chu, himself, on a breathless steed, stumbled across the battlefield.“Why didn’t you return?”panted the King.“I—I—I——” stammered General Chang.But the King said more.“The Tartars swooped down just a few hours ago, carrying off my Queen, raiding my treasury (though it was empty), and forcing me to flee for my life.They carried off the Queen.”

“How terrible,” exclaimed General Chang, looking into his sleeve. “And my army is so tired that it can’t march a step—besides the roads will soon be pu neng chu (can’t go) with the rain.”

HIGH AS HAN HSIN

Han Hsin was not at all high as to stature. He was short, short as a day in the Month of Long Nights. But as a leader of bow-drawing men, his place is high. As inventor of the world’s first kite, he rose very high indeed, and that accounts for the saying, “High as Han Hsin.”

The night that saw Han Hsin’s birth was no ordinary night.It was a night of fear and grandeur.The Shen who places the stars in the sky had a shaking hand that eve.His fingers were palsied and could not hold.Star after star dropped down toward earth, and the people prayed and wept, the while they exploded firecrackers.It’s a sinister sign when the stars tumble out of the sky.This the people knew.Therefore, they trembled.

But, amid the falling stars, was one that rose, as if the Shen had tossed it, as if the Shen had thrown it high.One large star mounted higher and higher the while its companions fell.Wise men, astrologers, they who scan the heavens, said: “The stars that fall—are mighty men who die.The star that rises—that is the star of a future great man—born this night.”

The wise men of the village kept careful watch over Han Hsin.He had been born on the night of the Rising Star.They thought perhaps he might be the ward of the Star.They watched closely for signs to strengthen their belief.But for some years Han Hsin disappointed them.He rattled his calabash in an extremely ordinary manner.There was no hint of greatness in the way he bounced a ball.Yet the astrologers held to their faith and watched—and finally were rewarded.

There came a rain, not a hard rain, nevertheless a wetting rain, sufficient to drive the villagers under shelter.But Han Hsin remained in the open where quick drops pelted.A foolish villager noticed him and said, laughing: “Look you at our future great man.He knows not enough to seek cover from the storm.Ho.Ho.Ho.How wise.”

An old astrologer said: “Hush, Chieh Kuo (Dunce), do you not see that the youth makes a bridge? Come with me.” They went closer to have a more complete view. The flowing water had formed a little island in the street. Upon the island were many ants. As the water rose, the island grew smaller—and the number of ants grew smaller, many being swept away to their death. Han Hsin raised a bridge from island to mainland. The ants quickly discovered his bridge and crossed to safety. “It is a sign,” said the old astrologer, “Chi li (a good omen). He has befriended the ants. The ants will remember. Some day they will do him an equal service—helping him to become great.”

Han Hsin discovered in the King’s paved road a hatchet of better than fair metal.None of the villagers could prove ownership.Little Han was permitted to keep his treasure.Quite soon a spirited chopping was heard—steel ringing upon stone.A foolish villager said: “Look.Han Hsin uses his fine hatchet to chop the old millstone—thus demonstrating his great genius.Ho.Ho.Ho.He uses valuable edged steel to chip stone.”

The old astrologer said, “Hush, Sha Tzu (Imbecile), come with me, and behold.” A wornout millstone lay at the edge of the road. Through the hole in its center grew a bamboo tree. The hole was small. Already it hindered the tree’s growth. Retarded as it was, the bamboo could never reach a full growth. Han Hsin belabored the stone till it split in two pieces. Then there was plenty of room for the tree. There was nothing to “pull its elbow.”

“That is good,” asserted the astrologer.“He saves the bamboo from death.Some day the bamboo will reward him—help him to become great.”

Shortly afterward, the astrologer gave Han Hsin a note of recommendation to the King. Han went to the King, seeking employ. He wished a command in the army. But His Majesty was in a sulky mood and would not see the boy. Therefore, Han continued his journey into Chin Chou, a neighboring country. He went to the ruler, Prince Chin, and exhibited his note. The prince read—and laughed. “You are too small to serve in my army. My soldiers are giants, all—very strong. You—are Ko Tsao (Little hopping insect). No.” Han solemnly declared that his strength was that of a river in flood, and begged for a trial. “Well, if you are determined,” said the prince, “take my spear and raise it above your head.” The prince’s spear was solid iron from point to heel, and longer than the mast of a sea-venturing junk. Furthermore, it had been greased with tiger fat to prevent rust. Han grasped the spear to raise it. His fingers slipped. Down crashed the heavy weapon. “Take whips and lash him out of the city—clumsy knave that he is,” Prince Chin roared in a great voice—angrily. The spear had missed His Royal Person by the merest mite.

An old councillor spoke.“Your Highness, surely it cannot be that you intend to let the rogue live?He will some day return with an army to take revenge.”“Nonsense,” said the prince.“He is no more than an ant—and idiotic besides.How could such a fellow secure an army?”“Nevertheless, I fear the ant will work your downfall.He must be killed.”The councillor insisted.He argued so strongly for Han’s death that, rather than hear more, the prince consented.“It is useless.But do as you wish.Send a squad of horse to overtake him and fetch back his head.”

When Han Hsin beheld the soldiers approaching at top speed, there was no doubt in his mind as to what harsh errand brought them.He knew they intended to have his head.But Han, having lived so long with his head, had become fond of it, and preferred to keep it on his shoulders.But how?How could it be saved?There was no escape by running.There was no place to hide.The boy must use his wits.

Hastily tying a cord to his bamboo staff, he threw the staff into a tiny, shallow puddle of water that lay beside the road. The soldiers galloped up to find him seated on the bank—fishing—and weeping. “And what ails you, simpleton?” a soldier asked. “Have you lost your nurse?” Between sobs Han answered, “I am hungry and I can’t catch any fish.” “What a booby,” said another soldier. “He fishes in a puddle no larger than a copper cash.” “Look,” said yet another, “he throws in the pole, and holds the hook in his hand. What a chieh kuo; as foolish as Nu Wa, who melted stones to mend a hole in the sky.”“Do you suppose this is the creature we were told to kill?”He was answered: “Nonsense.Prince Chin doesn’t send his cavalry to kill an ant.Spur your horses.”

When the troops returned and reported their lack of success, there was much talk.The councillor raged, offering to resign.He was positive that so long as Han Hsin lived the government would be in danger.He was bitter because the troops had mistaken Han’s cunning for imbecility.Merely to humor the councillor, Prince Chin mounted a horse and galloped away with his troops.

Han Hsin put his best foot foremost, hurrying toward the border.He longed to trudge the turf of his own country once more.It was not that homesickness urged his steps.Han felt reasonably sure that his friends, the soldiers, would shortly take the road again.The next time they might not be so easily deluded.Therefore, he hastened.But it was useless.His own country was still miles distant when he beheld the dust of men who whipped their horses.

It is not pleasant to have one’s head lopped off. At times it is almost annoying. Han thought quickly. Near by was a melon patch. The melons were large in their ripeness. Upon a huge striped hsi kua the boy sat him down and wept. The tears coursed down his cheeks, and his body shook with sobbing. Undoubtedly, his sorrow was great.

Prince Chin stopped his steed with a jerk.“Ai chi—such grief.Are you trying to drown yourself with tears?”“I—I—I am hungry,” stammered Han Hsin.“Hungry?Then why don’t you eat a melon?”“I would, sire, but I’ve lost my knife.So I must s-s-starve.”The prince was well assured that he had met with the most foolish person in the world.“What?Starve because you have no knife? .Strike the melon with a stone.Such a dunce.It would never do for me to behead this fellow.The Shen who watches over imbeciles would be made angry.”A trooper slashed a dozen melons with his sword.Surely, a dozen would save the idiot from starvation.Oh, what an idiot.

Han Hsin sat on the ground, obscuring his features in the red heart of a melon as the prince and his men departed.His lips moved—but not in eating.His lips moved in silent laughter.

Han Hsin bothered no more Kings with notes setting forth the argument that he had been born under a lucky star, and so deserved well.Quite casually, he fell in with King Kao Lin’s army.He received no pay.His name was not on the muster.He hobnobbed with all the soldiers and soon became a favorite.The boy had a remarkable memory.He learned the name of every soldier in the army.Further, he learned the good and bad traits of each soldier, knew who could be depended upon and who was unreliable.He knew from what village each man came, and he could describe the village with exactness.All from hearing the soldiers talk.

A fire destroyed the army muster-roll.Han Hsin quickly wrote a new list, giving the name of each man, his age, his qualities, his parents, and his village.King Kao Lin marveled.Shortly afterward, he added Han’s name to the list—a general.

Prince Chin made war upon King Kao Lin.He marched three armies through the kingdom, and where the armies had passed there was desolation, and no two stalks of grain remained in any field.Han Hsin moved against the smallest of the three armies.The enemy waited, well hidden above a mountain pass through which Han must march.It was an excellent ambush—there was no other passage.The mountain was so steep no man could climb it.

Han caused his soldiers to remove their jackets and fill them with sand, afterward tying bottom and top securely.The sand bags were placed against a cliff, to form a stair way.Up went Han and his men, to come upon the enemy from behind and capture the whole army—cook and general.

The second hostile army retreated to the river Lan Shui.It crossed the river, then burned all boats and bridges.So safe from pursuit felt the hostile general, he neglected to post sentries.Instead, he ordered all the men to feast and make pleasure.Han Hsin ordered his men to remove the iron points from their spears.The hollow bamboo shafts of the spears were lashed together, forming rafts.Armed only with light bows the men quickly crossed Lan Shui River and pounced upon their unready enemy.The feast was eaten by soldiers other than those for whom it had been intended.

Prince Chin led the third and largest army.He had far more braves than Han commanded.There could be no whipping him in open battle.In strategy lay the only hope.Han Hsin clothed many thousand scarecrows and placed them in the battle-line—a scarecrow, a soldier—another scarecrow, another soldier.In that manner, to all appearance, he doubled his army.Forthwith, he wrote a letter demanding surrender—pointing out that since his army was so much larger than Chin Pa’s, to fight would be a useless sacrifice.

Prince Chin took long to decide upon his course.So long it took him that Han grew impatient and sat down to write again.While he wrote, a strong wind broke upon the camp.The papers on Han’s table were lifted high in air.Higher and higher they swirled, higher than an eagle—for the Shen of Storms to read.Han’s golden knife, resting on a paper, was lifted by the wind, transported far over the foeman’s camp.

Immediately an idea seethed in the leader’s mind. If a small piece of paper could carry a knife, might not a large piece carry the knife’s owner? Especially, when that owner happened to be not much more weighty than a three-day bean cake? It seemed reasonable. Again the little general took spears from his soldiers. The iron points were removed and the long bamboo shafts were bound together in a frame. Over the frame was fastened tough bamboo paper in many sheets. Away from prying enemy eyes, the queer contrivance was sent into air. It proved sky-worthy, lifting its maker to a fearsome height. Thus was the feng cheng invented. Thus was the kite, little brother of the aeroplane, invented by Han Hsin.

The night showed no moon.Not a star had been lighted.The wind blew strong, with an eerie whistling.It was such a night as demons walk about their mischief, and honest men keep under their quilts.Out of the sky above the enemy camp came a great flapping sound.Could it be a dragon?All eyes peered upward through the darkness.Two red eyes appeared.Nothing more could be seen.Only the two evil eyes.A voice came from the sky.“Return to your homes,” boomed the voice.“The battle is lost.Return to your homes, ere they too are lost.”The men of Chin shook with their fear.The Shen of the sky had spoken.They had heard his voice.They had heard the flapping of his wings.They had seen his red and terrible eyes.How could the men of Chin know that the words they heard were uttered by Han Hsin?How could they know that the flapping was caused by a man-made thing, later to be named “feng cheng” (kite)?And how could they know that the eyes were mere bottles filled with insects called “Bright at night (Fireflies)”?The men of Chin could not know.They loosened the ropes of their tents—and the tents came down.

Prince Chin tried in vain to hold his followers.No longer followers were they.They were fugitives, fleeing to their homes.Only a few hundred remained true to their prince.Doubly armed with the weapons that had been thrown away, they ascended a steep and rocky hill, there to make their last great fight.

But Han Hsin had anticipated just such action, and had prepared for it.Unseen, he had slipped through the enemy lines and climbed the hill.With a brush dipped in honey he wrote words upon a stone.As he wrote, came hungry ants.The ants came—to aid—and to feast.Soon the stone was black with a crawling multitude.

Prince Chin scaled the hill to its summit.Ten thousand swords could not dislodge him from those rocks.He would make the enemy pay a red price for success.His gaze fell upon the rock.He saw a host of ants forming characters that read “The Battle is Lost.”His men also beheld, and they said, “The ant is wisest of all animals.Let us crawl in the dust, for we are conquered.”

So, Han Hsin victored over the three hostile armies.His country was invaded no more.In time it became really his country, for he ruled it—as a King—ruled it well.But now his wise rule is forgotten.He is remembered as the man who first made kites.

CONTRARY CHUEH CHUN

The most contrary man that ever drew a full dozen breaths was Chueh Chun, living in Tien Ting Village, thirty minutes by donkey, by up and down very bad road, north of the Great Wall, the far-famed Chinese Wall.

Queer Chueh Chun had been named Ma Tzu by his honorable parents.He had been named Ma Tzu, which means Face Rather Ugly.He, himself, changed his name to Chueh Chun, which means Absolutely Beautiful.

The good people of Tien Ting Village lived tidily in made houses, above ground.Chueh Chun lived in a cave, a deep and winding fox den, below ground.Such of the neighbors as were permitted by law to wear hats, wore little round hats, on their heads.Chueh Chun wore hats on his feet.Moreover, he wore straw hats in winter, fur in summer.On his head perched an ancient sandal.He pretended that the arrangement was excellent.The sandal shaded his eyes, yet permitted his head to remain cool.

The neighbors when going upon long journeys commonly rode their shaggy mountain ponies.Chueh Chun when setting forth on an arduous trip—say fifty miles—was most likely to walk.But to go from his fox lair home to the nest of his speckled hen, he invariably rode a little donkey.

Yu Yuch Ying, aunt to Chueh Chun, willed her obstinate nephew thirty thousand cash, just when his purse was at its flattest.The neighbors gathered round Chueh Chun to congratulate and envy him.Said they: “What a fortunate person are you, dear Chueh Chun.The thirty thousand cash that your late lamented Aunt Yu Yuch Ying left will set you up in noble style.A most opportune windfall was that.Plenty of luck you have.”

But Chueh Chun nodded his head.He always nodded his head to show that he differed.“Quite the contrary,” said Chueh Chun, “I fear me, honorable neighbors, that my aunt’s bequest is an ill thing altogether.It is luck the worst.Thirty thousand cash are so heavy that I shall be compelled to make at least two trips to fetch them.Besides, the beggars will be annoying me without let-up from break of day till I break their heads.And think of thieves.The money will bring me ill, I am sure.”And Chueh Chun laughed heartily, for that was his way of expressing sorrow.

However, Chueh Chun’s excellent wife knew how to manage him.She said: “Quite right.If I were you, I wouldn’t dream of going for the fortune.And I wouldn’t once think of riding the donkey, not once.”And she spoke as if she meant her words.

Therefore—upon his donkey—the contrary husband started for Tsun Pu, where his beloved aunt had lived and left riches.Immediately outside Tien Ting Village the traveler was forced to cross a river.The current was swift and it washed the hat-shoes from Chueh Chun’s feet.Down the stream swirled the hats, with their owner in splashy pursuit.The neighbors, who had gathered to bid old Contrary a fine journey, were loud in lamentation over his loss.They exclaimed, beating their breasts: “Oh, Chueh Chun, we are so sorry that you have lost your hat-shoes, so utterly sorry.With our eyes we weep for you and cry ‘alas.’What terrible luck.It is demon-sent luck in truth.”

But Chueh Chun paused in his splashing and answered them: “Why, no.I dare say it is not bad luck at all.Quite the opposite, my esteemed neighbors, it may be very fortunate indeed.”He wept to show that he was well pleased.

Meanwhile, the onward swept hat-shoes disappeared from view.Chueh Chun raced along the bank, calling, and anxiously scanning the water for a trace of his lost property.The neighbors, too, hurried after, one leading the donkey.Rounding a willow-draped elbow of the river, Chueh Chun stumbled over a boat that had drifted ashore.He fell headlong and heavily, his chin plowing a prodigious furrow in the sand.Up panted the neighbors, shouting: “Alas, likewise alack.What woe.Such woe.Poor Chueh Chun, how we ache for you.Our own bones pain out of sympathy.What a horrible calamity.”

Chueh Chun stretched out a hand to pick up his two hat-shoes, drifted against a willow bough.Said he, rather indistinctly because of the sand in his mouth: “Nothing of the kind, greatly respected neighbors.My fall was most beneficial, for it placed me nearly atop my lost shoes.Otherwise I might never have found them.”He sobbed to prove his joy.

It is doubtful if the others heard.They, inquisitive fellows that they were, had hands and eyes and tongues busy as they investigated the boat that had caused Chueh Chun’s downfall.Lifting a drab and unpromising rain-cloth, they discovered underneath a cargo of precious tribute silks—only the best—stuffs such as are sent in tribute to His Majesty, The Emperor.There were bales of silk and sewn garments of silk.There were reds and greens and purples, brown and black and gold.Orange, blue, and pink, they surpassed the rainbow in vivid hue.“How marvelous,” gasped the neighbors.“Your fortune is made, Chueh Chun.What stupendous good luck.We who have always been your truest friends, aiding you with turnips and money in time of need, now rejoice with you.”

Chueh Chun nodded.“I must beg leave to disagree on that,” was his contradiction.“It is no very good luck.I would sooner have stepped on a fretful tiger.Really, it is terrible—finding this boat.”

The neighbors squinted eyes at each other and spoke.“A pity that you won’t take of the find.Howbeit—good for us.We can make profitable use of these things.”They were silly to say that.

Chueh Chun promptly loaded his donkey with silks, a burden worth, even in a beggars’ market, double or more the thirty thousand cash left by his aunt.He donned a most sightly lilac-colored coat and departed.

Thus with his donkey laden and his own back resplendent, Chueh Chun fared onward toward Tsun Pu.Scarce had he gone two li when a band of brigands espied him.“There goes old Chueh Chun,” said a brigand.“He is too poor to rob.That donkey of his is older than my own dear great-grandfather, and possesses a most deplorable temper.”But the robber chief spoke.“Nonsense, you shallow pate.Look at his lilac robe.Look at the silks upon his beast.We could scarcely have better fortune though we opened sacks within our noble Emperor’s treasury.”So the robbers fell upon Chueh Chun and stripped him of his stuffs.His donkey, his robe, his purse, all they took.

It was a well-plucked traveler who returned to Tien Ting Village and related his misadventure.The villagers, to a man, sympathized greatly.“Our hearts go out to you, most excellent Chueh Chun,” they condoled.“Undoubtedly, you have suffered.How you must grieve.And we also grieve.It is all pleasure swept away.”

Stubborn Chueh Chun could not agree.Said he: “Who knows but that it was good luck?Had I continued through the mountains I might have been killed by falling rocks.Think of that.Beyond doubt the robbers saved my life.Yet you, my supposed friends, say it was bad luck.”

Early next morning, Chueh Chun’s ancient donkey returned to the village.She had broken loose from the brigands and ambled home with all her load of silks intact.How the neighbors rejoiced.A person might easily have thought that the little donkey belonged to them, so jubilant were they.“Oh, Chueh Chun, awake,” they screamed.“Here is your donkey, all hearty and hale—with not so much as a yard of silk missing.What wonderful, wonderful luck.”

Chueh Chun said: “I’m afraid, good gracious yes, it’s very bad luck.No good can come of this.It’s unfortunate as can be.Alas.Alas.”Nor was he far wrong.That very morning, while ministering to a wound upon the donkey, that sinful little beast kicked with such violence as to break her master’s leg.The somewhat inquisitive neighbors gathered, as bees gather to the blossoming beans.“Oh.Oh.Oh,” they screamed.“What is the matter?Did the shameless donkey kick our handsome neighbor?”

“Truly, she did,” laughed Chueh Chun.“So hard that I think my leg has come apart.”And as he thought, so it was.He could not walk.

The neighbors redoubled their wails, asking each other, “Is not that the extreme height of ill fortune?”

“Not at all,” denied old Chueh Chun, perhaps a trifle grumpily.“In my opinion it may be a blessing.It, no doubt, will save me from something worse.Besides, it convinces me that my donkey is very strong, despite her age.”

By darkest midnight the Khan of the warlike Tartars, with fifty thousand men, swooped down to raid such villages as had, rather foolishly, been built outside the Great Wall.Tien Ting suffered.Every able-bodied man was taken prisoner.Only the very young, the extremely ancient, the lame, the blind, and the bedridden were left in their homes.Chueh Chun was one of those thus spared.Lameness and age were in his favor.By torchlight a toothless, grinning old neighbor dropped into Chueh Chun’s cave to say that the danger was no more.“The Tartars are gone, my admirable friend, Chueh Chun—and so are all of our young men, and our goods, even to house chimneys.I think you and I are about the only ones spared.How fortunate we are.”

“It may be all very fortunate for you,” put in Chueh Chun, “but as for me, I have a feeling that things could be much better, and still be not so good.I wish the Tartars had carried me into captivity astride my own poor lost donkey.”For, of course, his donkey was gone again.

With the dawning, His Majesty, The Emperor Ching Tang, entered the village to learn of its losses.He was told that all of the men, save half a dozen, Chueh Chun among them, had been carried off.“Why wasn’t such a one taken?”asked the Emperor.He was told: “A cripple for ninety years and a day.”“Why wasn’t Chueh Chun taken?”asked the Emperor.“Because, Noble Majesty,” answered a villager, kneeling three times and knocking his head on the ground thrice with each kneeling, “because, most gracious light of the sun and beauty of the moon, lord of the earth and sea and sky, Chueh Chun was kicked by his own donkey, and I well remember his saying at the time that it was extremely fortunate his leg was broken—a blessing—those were his words.And they were true.”

“What say you?”thundered the Emperor “A blessing—to be crippled?Why then this Chueh Chun must have known beforehand that the Tartars were coming to carry away my people.He must have known it, and knowing, gave us no warning.Bid this traitorous fellow appear.Soldiers—go.Headsman—draw your sword.”

Fortunately, Chueh Chun’s wife heard the Emperor’s command.Swiftly she ran home.As she entered the cave Chueh Chun sneezed.“Kou Chu.”The sneeze led to an excellent idea.Said the wife: “Aha.Aha,” with much emphasis.“You were out in your boat on the river last week, and now you have a cold.”Adding with proper severity, “Don’t you dare go near the river again.Do you hear?”She knew very well what would happen.“My husband—come back.”

Lame as he was, Chueh Chun promptly left the cave and got into his boat.The good wife smiled and screamed, “Don’t row with such vigor.”

Soldiers ran to the bank of the stream and called, “Come back.”And louder they shouted, “Come back.”That was extremely foolish of them.They should have said, “Go on.”

Contrary to the last, Chueh Chun sat the wrong way in his boat and rowed for dear life.

PIES OF THE PRINCESS

Three plump mandarins hid behind a single tiny rose bush. The chancellor crawled under a chair. All courtiers fell upon their chins, and shivering, prayed that soft words might prevail.

For no slight reason did they shiver and hide and pray.King Yang Lang was angry.And he was an old-fashioned monarch, living in the long ago.Nowadays, any greasy kitchen lout may tweak a King’s beard, and go forth to boast of his bravery.But then-a-days, Kings were Kings, and their swords were ever sharp.

King Yang Lang was such a ruler—and more angry than is good to see.His face was purple, and his voice boomed like a battle drum.“Keeper of the Treasury, has all my gold been used to make weights for fishing lines?”

Time after time the treasurer knocked his head against the paving.“Most Glorious and Peaceful Monarch, your gold is so plentiful that seven years must pass before I can finish counting the larger bars—ten years more for the smaller.”

That was rather pleasant news.The King’s voice lost some of its harshness.“What of ivory?Has all my ivory been burned for firewood, a pot to boil?”

The treasurer continued to knock his Head.“Supreme Ruler of The World and The Stars, your ivory completely fills a hundred large and closely guarded vaults.”

The King hadn’t dreamed that his wealth was so vast.His voice was not more moderately furious as he asked: “For what reason have you disposed of my jade?Do you mean to say that my jade has been used to build a stable for donkeys?”

Tap, tap, tap, went the treasurer’s head on marble paving: “Oh, Powerful Potentate, the store of green jade grows larger each day.Your precious white jade is worth more than green, and gold, and ivory combined.It is all quite safe, under lock and key and watchful spears.”

The King was astonished and put in somewhat better humor.His voice was no louder than thunder as he again questioned the treasurer.“Then why, tell me why is my daughter, the Princess Chin Uor, not given suitable toys.If the treasury holds gold and ivory and jade, why is my daughter compelled to use toys of common clay?”

The treasurer could not explain: “Monarch whose word compels the sun to rise, we have pleaded with the wee Princess Chin Uor.We have given her a thousand dolls of solid gold, with silver cradles for each, cradles set with rubies—and the dolls have eyes of lustrous black pearl.For the princess we have made ivory cats, and ivory mice for the cats to catch—two thousand of each.For the princess we have fashioned from jade, lovely tossing balls, wonderful dishes, and puppy dogs that bark and come when called.Yet, the princess ignores these things .and makes mud pies—Mud PiesMightiest Majesty, I do not know why, unless it may be that the princess is a girl, as well as a princess.”

A trifle relieved, King Yang Lang passed into the garden.Beside the river bank he found his daughter, the Princess Chin Uor, or Princess Many Dimples—for that is the meaning of Chin Uor.Nurses standing near kept watch upon wheelbarrows spilling over with golden dolls.But Chin Uor had no thought for such toys.Her royal hands shaped the tastiest of mud pies.Very pretty pies they were—made of white clay.

The King said: “Littlest and most beautiful daughter, the golden dolls are longing for your touch.Why do you not please them?It is not seemly for a princess to dabble in clay.Then why do you make pies?”

The princess had a very good answer ready.“Because, Daddy, I want to make pies.This nice large one is for your dinner.”

The King was so shocked that he could say nothing more.Mud pies for a King’s dinner?Such nonsense.His Majesty was scandalized at the thought.He departed in haste.

But the Princess Chin Uor smiled and kneaded more and more pies.And when she had made enough she placed them in a wheelbarrow and trundled them to the palace.