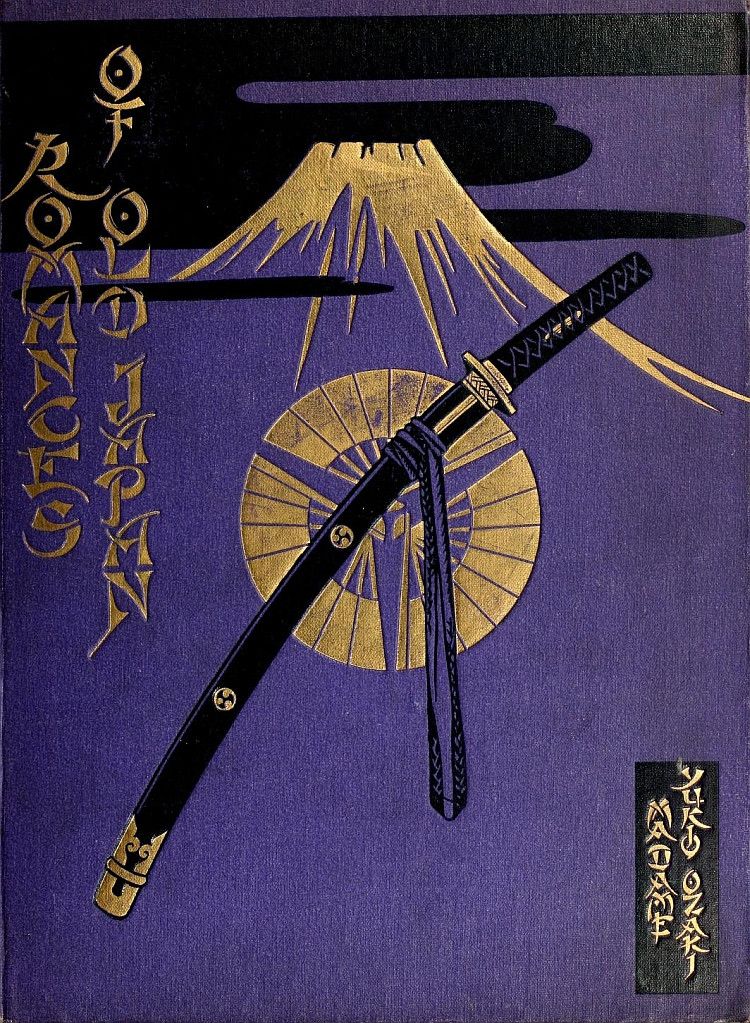

Romances of Old Japan / Rendered into English from Japanese Sources

Play Sample

[1] 1513, date of Ota Dokan's death.

[2] Kago = palanquins.

[3] Horai Dai, the Eastern fairyland, where death and sickness never come, and where the fabulous old couple of Takasayo, paragons of conjugal felicity and constancy, live for ever in the shade of the evergreen pines, while storks and green-tailed tortoises, emblems of prosperity and ten thousand years of life, keep them company.

[4] Shoji, the sliding screens which takes the place of doors and windows in a Japanese house—the framework is of a fine lattice-work of wood, covered with white paper sufficiently transparent to let in the light.

[5] The old Japanese pillow was a wooden stand, on the top of which was a groove; in this was placed a small roll of cotton-wool covered with silk or crêpe, etc.

THE REINCARNATION OF TAMA

"Felt within themselves the sacred

passion of the second life.

Hope the best, but hold the Present

fatal daughter of the Past.

Love will conquer at the last."

TENNYSON

N.B.—It is a common Japanese belief that the soul may be re-born more than once into this world.A Buddhist proverb says:

Oya-ko, is-sé

Fufu wa, ni-sé,

Shu ju wa, sansé

Parent and child for one life;

Husband and wife for two lives;

Master and servant for three lives.

Under the strong provocation of the passions of love, loyalty and patriotism, the soul may be reincarnated as many as seven times.The hero Hirose, before Port Arthur in 1904, wrote a poem during the last moments of his life saying that he would return seven times to work for his country.

THE REINCARNATION OF TAMA

Many years ago in Yedo,[1] in the district of Fukagawa, there lived a rich timber merchant. He and his wife dwelt together in perfect accord, but though their business prospered and their wealth increased as the years went by, they were a disappointed couple, for by the time they had reached middle age they were still unblessed with children. This was a great grief to them, for the one desire of their lives was to have a child.

The merchant at last determined to make a pilgrimage to several temples in company with his wife, and to supplicate the gods for the long yearned-for joy of offspring.When the arduous tour was over they both went to a resort in the hills noted for its mineral springs, the woman hoping earnestly that the medicinal waters would improve her health and bring about the desired result.

A year passed and the merchant's wife at last gave birth to a daughter.Both parents rejoiced that the Gods had answered their prayers.They reared the child with great care, likening her to a precious gem held tenderly in both hands, and they named her Tama, the Jewel.

As an infant Tama gave promise of great beauty, and when she grew into girlhood she more than fulfilled that promise.Their friends all declared that they had never seen such loveliness, and people compared her to a morning-glory, besprinkled with dew and glowing with the freshness of a summer dawn.

She had a tiny mole on the side of her snowy neck.This was her sole and distinguishing blemish.

Tama, the Jewel, proved a gifted child. She acquired reading and the writing of hieroglyphics with remarkable facility, and in all her studies was in advance of girls of her own age. She danced with grace, and sang and played the koto enchantingly, and she was also accomplished in the arts of flower-arrangement and the tea-ceremony.

When she reached the age of sixteen her parents thought it was time to seek a suitable bridegroom for her.Very early marriages were the custom of the day, and besides that her parents wished to see her happily established in life before they grew older.As she was the only child, her husband would become the adopted son, and thus the succession to the family would be secured.However, it proved exceedingly difficult to find anyone who would meet all their requirements.

Now it happened that near-by in a small house there lived a man by the name of Hayashi. He was a provincial samurai, but for some reason or other had left his Daimio's domain and settled in Yedo. His wife was long since dead, but he had an only son whom he educated in the refinements of the military class. The family was a poor one, for all samurai were trained to hold poverty in high esteem; and to despise trade and money-making.

Both father and son led simple lives and eked out their small patrimony by giving lessons in the reading of the classics and in calligraphy, and by telling fortunes according to the Confucian system of divination.Both were respected by all who knew them for their learning and upright lives.

At the time this story opens the elder Hayashi had just died and the son, though only nineteen years of age, carried on his father's work.

The young man was strikingly handsome. Of the aristocratic type, with long dark eyes, aquiline features and a pale, cream-like complexion, he attracted notice wheresoever he went, and though shabbily dressed he always bore himself with great dignity. He was a musician and played the flute with unusual skill, and the game of go[2] was his favourite pastime, a taste which made him very popular with older men.

He often passed the rich merchant's house and Tama, the Jewel, noticed the young man coming and going with his flute.Questioning her nurse, she learned all there was to know about his history, his poverty, his scholarly attainments, his skill as a musician and the recent sorrow he had sustained in the death of his father.

Besides being attracted by his good looks, the beautiful Tama's heart went out in sympathy to the young man in his misfortune and loneliness, and she asked her mother to invite him to the house as her music-master, so that they might play duets together—he performing on the flute to her accompaniment on the koto

The mother consented, thinking the plan an excellent one, and the young samurai became a frequent visitor in the merchant's house. Tama's father was delighted when Hayashi proved to be an expert at go, and often asked him to come and spend the evening.As soon as dinner was over the merchant would order the chequer-board to be brought and Hayashi was then invited to try his hand at a game.

In this way the intimacy deepened till by degrees the young man was treated like a trusted member of the family.

The young master and pupil thus meeting day by day, presently fell in love, for heart calls to heart when both are young and handsome and the bond of similar tastes cements the friendship. Choosing themes and songs expressive of love they communicated their sentiments to one another through the romantic medium of music, and the two instruments blended in perfect harmony, the koto's accompaniment giving an ardent response to the plaintive melody of the young man's flute, which wailed forth the hopeless passion consuming his soul for the lovely maiden.

Tama's father was delighted when Hayashi proved to be an expert at go, and often asked him to come and spend the evening

Tama's parents were totally unaware of all that was happening, but her nurse soon guessed the secret of the young couple.The woman, who loved her charge faithfully and devotedly, could not bear to see her unhappy, and foolishly helped the lovers to meet each other in secret.With these unexpected opportunities they pledged themselves to each other for all their lives to come, and tried to think of some way by which they could obtain the old people's consent to their marriage.But Hayashi guessed that the merchant was ambitious for his daughter, and knew that it was improbable that he would accept a son-in-law as poor and obscure as himself.So he postponed asking for her hand until it was too late.

At this time a rich man whom Tama's parents deemed a suitable match for their daughter presented his proposals, and Tama was suddenly told that they approved of the marriage and that she must prepare for the bridal.

Tama was overwhelmed with despair.That day Hayashi had promised to come and play his favourite game with her father.The nurse contrived that the lovers should meet first, and then Tama told Hayashi of the alliance which had been arranged.Weeping, she insisted that an elopement was the only solution to their difficulties.He consented to escape to some distant place with her that very night.Gathering her in his arms he tried to still her sobbing, and Tama clung to him, declaring that she would die rather than be separated from him.

They were thus surprised by her mother, and their secret could no longer be concealed.Tama was taken from him gently but firmly and shut up like a prisoner in one room.The vigilance of the parents being in this manner rudely awakened, the mother never allowed the girl out of her sight, and Hayashi was peremptorily forbidden the house.

The young man, fearing the wrath of her parents, went to live in another part of the city, telling no one of his whereabouts.

Tama was inconsolable.She pined for her lover and soon fell ill.Her elaborate trousseau and the outfit for the bridal household was complete but the wedding ceremony had to be postponed.

Both parents became very anxious for, as the days went by, instead of getting better their daughter visibly wasted away and sometimes could not leave her bed, so weak did she become.To distract her mind they took her to places of amusement like the theatre, or to gardens noted for the blossoming of trees and flowers.Then finally they carried her to places like Hakone and Atami, hoping that the mineral baths and the change of air and scene would cure her.But it was all to no purpose, Tama grew worse in spite of the devotion lavished upon her.Seriously alarmed, the parents called in a doctor.He declared Tama's malady to be love-sickness, and said that unless she were united to the man she pined for that she might die.

Her mother now begged the father to allow the marriage with Hayashi to take place.Though he was not the man of their choice in worldly position, yet if their daughter loved him, it were better that she should marry him than that she should die.

But now arose a difficulty of which they had not dreamed.Hayashi had moved away no one knew whither, and all their frantic efforts to trace him were fruitless.

A year passed slowly by.When Tama was told that her parents had consented to her marrying her beloved, she brightened up with the hope of seeing him again, and appeared to regain her health for a short time.But as month followed month and he never came, the waiting and the sickening disappointment proved too much for the already weakened frame of the young girl.She drooped and died just as she had attained her seventeenth birthday.

It was springtime when the sad event occurred.Hayashi had never forgotten the beautiful girl nor the vows they had mutually plighted, and he swore never to accept another woman as his wife.He longed for news of Tama, but he realized how imprudent and blameable his conduct had been in entering into a secret love-affair with a young girl, and he feared that her father might kill him were he to return even for a single day to the vicinity.Weakly he told himself that she had in all probability forgotten him by this time and was surely married to the man of her parents' choice.

One fine morning he went fishing on the Sumida river.When evening began to fall he turned homewards.As he sauntered along the river embankment, the water lapping softly and dreamily at his feet, he was suddenly startled to see a girlish form coming towards him in the wavering shadows of declining day.Light as a summer zephyr she glided from under the arches of the blossom laden cherry-trees with the sunset flaming behind her.He remembered long afterward that she had seemed rather to float over the ground than to walk.

To his utter astonishment he at once recognized Tama, and his heart leapt with joy at sight of her.After the first salutations he looked at her closely and congratulated her on her good health and ever-increasing beauty.He then asked her to tell him all that had happened since they were cruelly parted.

In the saddest of tremulous voices Jewel answered: "After you left the house my old and devoted nurse was dismissed for having helped us to meet in secret.From that day to this I have never seen her, but she sent me word that she had returned to her old home."

"Then you are not married yet?"asked Hayashi, his heart beating wildly with hope as he interrupted her.

"Oh, no," replied Tama, looking at him strangely, "do you think that I could ever forget you?You are my betrothed forever, even after death.Do you not know that the dread of that marriage being forced upon me and my pining for you made me ill for a long time.Sympathizing with my unhappiness, my parents broke off my engagement and then tried to find you.But you had entirely disappeared leaving no trace behind.To-day I started out, resolved to find you with the help of my old nurse.I am on my way to her now.How happy I am to find you thus.Will you not take me to your house and show me where you live?"

He was suddenly startled to see a girlish form coming towards him in the wavering shadows

She then turned and walked with him as he led the way to their humble dwelling.Now that her parents had consented to her marrying him they need not wait long, he told himself.How fortunate he was that he should have gained such faithful and unchanging love as that of his beautiful Tama.

As they went along exchanging blissful confidences as to their undying love for one another, he told her of his oath never to wed another woman for her dear sake.

They entered the house together, the nearness of her sweet presence thrilling him to his finger-tips.Impatiently he knelt to light the lamp, placed ready on his low writing table, then with joy inexpressible at the anticipation of all that the future held for them, he turned to speak to her.

But to his utter bewilderment Tama was gone.He searched the house and garden, and with a lantern went and peered down the road, but she was nowhere to be seen.She had vanished as suddenly and mysteriously as she had appeared.

Hayashi thought the incident more than strange; it was eerie in the extreme.Returning alone to his empty room, he shivered as a chill of foreboding seemed to penetrate his whole being, withering as with an icy breath the newly awakened impulses of hope and longing.A thousand recollections of his love crowded upon him, and kept him tossing uneasily upon his pillow all through the night.With the first break of dawn he was no longer able to control his feverish anxiety for news of her, and rising hurriedly, he at once set out for Fukagawa.

Eagerly he hastened to the house of an old friend to make inquiries regarding the merchant's family and especially about Tama.To his dismay he learned that she had passed away but a few days before, and listened with an aching heart to the account of her long illness.And he knew that she had died for love of him.

He returned to his home stupefied with grief and tormented with self-reproach.

"Oh, Tama!Tama!My love!"he cried aloud in his anguish, as he threw himself down in his room and gave way to his despair."Had I but known of your illness I would have come to you.It was your spirit that appeared to me yesterday.Oh!come to me again!Tama!Tama!"

For weeks he was ill, but when he recovered and was able to think collectedly, he could not endure to live longer in such a world of misery. He felt that he was responsible for the untimely death of the young girl. To escape from the insupportable sorrows of life he decided to enter a Buddhist monastery, and joined the order of itinerant monks called Komuso[3]

Like the monks in the middle ages in Europe the Komuso enjoyed sanctuary. They were chiefly samurai who wished to hide their identity. Sometimes a breach of the law, such as the killing of a friend, obliged the samurai to cut the ties which bound him to his Daimio; sometimes a family blood-feud forced him to spend his years in tracking down his enemy; sometimes it was disgust of the world, sorrow or disappointment, as in the case of Hayashi: these various reasons often caused men to bury themselves out of remembrance in the remote life of these wandering monks.

The Komuso were always treated with great respect, they enjoyed the hospitality of inns and ships, and a free pass unquestioned across all government barriers.

They wore the stole but not the cassock, and they did not shave their heads like the priesthood.They were distinguished by their strange headgear, which was a wicker basket worn upside down, reaching as far as the chin and completely hiding the face.The rules of their order forbade them to marry, to eat meat, or to drink more than three cups of wine, and when on duty they might not take off their hats or bow to anyone, even to their parents.Outside these restrictions, though nominally priests, their lives were practically those of laymen, and when not on service they spent their time much as they liked in practising the military arts or in study.

As a mental discipline the Komuso were under obligation to go out daily to beg for alms, holding a bowl to receive whatever was bestowed upon them. They affected flute playing. This instrument was cut from the stem nearest the root, the strongest part of the bamboo, and was thus able to serve a double purpose. It gave the monk, who carried nothing with him, the means of earning his daily food, and when necessary was used as a weapon in self-defence.

Hayashi, being skilful with his flute, chose the life of the Komuso as being the best suited to him.

Before leaving Tokyo he visited the temple where his lost love was buried and knelt before her tomb. He dedicated his whole life to praying for the repose of her soul and for a happier rebirth. Her kaimyo (death-name) he inscribed on heavy paper, and wheresoever he went he carried this in a fold of his robe where it crossed his breast. It was, and still is, the custom of the Komuso to perform upon the flute as a devotional exercise at religious services.

As each year came round he always made his way to some tranquil spot and rested from his penitential wanderings on the anniversary of the death of Tama.

Staying in an isolated room he then set up her kaimyo in the alcove, and placing an incense burner before it, kindled the fragrant sticks and kept them alight from sunrise to sunset. Kneeling before this temporary altar he took out his flute, and pouring the passionate breath of his soul into the plaintive, quivering notes, he reverently offered the music to her sweet and tender spirit, remembering the delight she had always taken in those melodies before the blossom of their love had been defrauded of its fruit of consummation by the blighting blast of interference.

Hayashi visits the temple where his lost love was buried, and dedicates his whole life to praying for the repose of her soul.

And gradually, as time went by, the burden of sorrow and the tumult of remorse slipped from his soul, and peace and serenity, the aftermath of suffering, came to him at last.

He roamed all over the country for many years, and finally his journeyings brought him to the mountainous province of Koshu.It was nightfall when he reached the district and he lost his way in the darkness.Worn out with fatigue, he began to wonder where he should pass the night, for no houses were to be seen far or near, and everywhere about him there was nothing but a heaping of hills and a wild loneliness.

For hours he strayed about, when at last, peering into the gloom far up on the mountain side, a solitary light gleamed through the heavy mists.Greatly relieved he hastened towards it.

As soon as he knocked at the outer door of the cottage a ferocious looking man appeared.When the stranger asked for a night's shelter he morosely and silently showed him into the single room which, flanked by a small kitchen, comprised the whole dwelling.Hayashi, furtively gazing round him, noticed that there were no industrial implements to be seen, but that in one corner were standing a sword and a gun.

The host clapped his hands.In answer to the call a young girl of about fifteen years of age appeared.He ordered her to bring the brazier and some food for the guest.Then arming himself with his weapons, he left the house.

The damsel waited on Hayashi attentively, and as she went to and fro from the kitchen she often glanced appealingly at him.Her attitude was that of one frightened in submission, and Hayashi wondered how she came to be there, for, though begrimed with work, he could see that she was fair and comely, and her deportment was superior to her surroundings.

When they were left alone the girl came and knelt before him, and bursting into tears sobbed out "Whoever you may be I warn you to escape while there is yet time.That man whose hospitality you have accepted is a brigand and he will probably kill you in the hope of plunder."

Hayashi, with his heart full of compassion for the young girl, asked her how it was that she came to be living in so wild and desolate a place, and the tale she told him was a pitiful one of wrong.

"My home is in the next province," she said, as she wiped away the tears with her sleeve."Just after my father's death this robber entered our house and demanded money of my mother.As she had none to give him he carried me away, intending to sell me into slavery.Soon after he brought me to this house, he was wounded on a marauding expedition, and has since been confined to the house for a month.Thus it is that you find me here still.But he is now recovered and able to go out once more.I implore you to take me with you, otherwise I shall never see my mother again and my fate will be unendurable."

Being of a chivalrous nature Hayashi's heart burned within him at the sad plight of the little maid, and catching her up he fled out of the robber's den into the night.

After some time, when well away from the place, he set her down and they walked steadily all night.By dawn they had crossed the boundary of Koshu and entered the neighbouring province.Once on the high road the district was familiar to the girl and she gladly led the way to her own home.

The delight of the sorrowing mother on finding her kidnapped child restored to her was great and unrestrained.She fell at his feet in a passion of gratitude and thanked him again and again.

In the meantime the rescued girl came to thank her deliverer.Hayashi gazed at her in astonishment.Her appearance had undergone an extraordinary transformation.No longer the forlorn, neglected drudge of the day before, a beautiful girl stood before him.And wonder of wonders!She was the living image of what his lost Tama had been years ago.The tide of the past swept over him with its bitter-sweet memories, leaving him speechless and racked with the storm of his feelings.Not only was the likeness forcibly striking, but he also beheld a little mark, the exact replica of the one he so well remembered on Tama's snowy neck.

He had thought that in the long years of hardship and renunciation of the joys of life the tragic love of his youth lay buried, but the shock of the unmistakable resemblance left him trembling.

In a few minutes he was able to control his emotion and the power of speech returned to him.

"Tell me," he said, turning to the mother, "have you not some relatives in Tokyo?Your daughter is like one whom I knew many years ago, but who is now dead."

The woman regarded him searchingly and after a few moments of this close scrutiny, she inquired:

"Are you not Hayashi who lived in Fukagawa fifteen years ago?"

He was startled by the suddenness of the question, which showed that his identity was revealed and that she knew of his past.He did not answer but searched his brain, wondering who the woman could possibly be.

Seeing his embarrassment she continued, now and again wiping the tears from her eyes: "When you came to the house I thought that your voice was in some way quite familiar to me, but you are so disguised in your present garb that at first I could not recall who you were.

"Fifteen years ago I served in the house of the rich timber merchant in Fukagawa and often helped O Tama San[4] to meet you in secret, for I felt great sympathy with you both, and if a day passed without her being able to see you, Oh! she was very unhappy. Her parents were furious at the unwise part I had played and I was summarily dismissed. I returned home and was almost immediately married. Within a year I gave birth to a little daughter. The child bore a striking resemblance to my late mistress and I gave her the name of Jewel in remembrance of the beloved charge I had nursed and tended for so many years. As she grew older not only her face and figure, but her voice and her movements all vividly recalled O Tama San. Is not this an affinity of a previous existence that my child should be saved by you who loved the first Tama?"

Then Hayashi, who had listened with rapt attention to the woman's strange story, asked her the date of the infant's birth.

Marvellous to relate it was the very day and hour, for ever indelibly engraven on his memory, that Tama, his first love, had appeared to him on the bank of the Sumida river in the springtide fifteen years ago.

When he told her of this uncanny meeting the woman said that she believed her daughter, the second Tama, to be the re-incarnation of the first Tama.The apparition he had seen was the spirit of his love who had thus announced her rebirth into the world to him.There could be no doubt of this, for had not Tama told him herself that she was on her way to her old nurse.So strong was the affinity that bound them to each other that it had drawn Tama from the spirit-land back to this earth.

"Remember the old proverb, the karma-relation is deep," she added in conclusion.

Later on she besought Hayashi to marry the second Tama, for she believed that only in this way would the soul of the first Tama find rest.

But Hayashi, thinking that the great difference in their present ages was an obstacle to a happy union, refused on the score that he was too old and sad a man to make such a young bride happy.He decided, however, to stay on in the little household for a while, and to give any possible comfort and help to the old nurse whose loyal devotion to her mistress had figured so prominently and fatefully in his past.

Thus several months elapsed, bringing with them great and radical changes in the land. The Restoration came to pass, and the new regime was established with the Emperor instead of the Shogun at the helm of State. Schools were founded all over the country, and amongst many other old institutions the order of the Komuso monks, to which Hayashi belonged, was abolished by an edict of State.

Hayashi, during his stay in the village, had won his way into the hearts of the people and they now begged him to remain as teacher in the new school, a position for which he was peculiarly fitted by the classical education he had received from his father.He consented to the proposition which solved the problem of his future, for under the new laws it was forbidden him to return to his old life.

The mayor of the place was also much attracted by Hayashi's superior character and dignity, and learning of the sad and romantic history of his past, and believing, as all Japanese do, in predestined affinities, persuaded him that it was his fate, nay more, a debt he owed to the past, to marry Tama, the second, the re-incarnation of his first love.

The marriage proved a blessed one.The house of Hayashi prospered from that day forth and as children were born to them the joy of their lives was complete.

[1] The old name for Tokyo.

[2] Go, a game played with black and white counters—more complicated than chess.

[3] The sect was introduced from China in the Kamakura epoch (1200-1400), but it never became popular in the land of its adoption. Under the Tokugawa Government (1700-1850) the Komuso were used as national detectives, but the privileges they enjoyed led to the abuse of the order by bad men, and it was abolished at the time of the Restoration. Later on the edict was rescinded, and these men in their strange headgear may be seen to this day fluting their way about the old city of Kyoto.

[4] In speaking women use the polite forms of speech, whereas men drop them. The "O" is the honorific prefix to a woman's name and "San" or "Sama" is the equivalent of Mr. Mrs. or Miss according to the gender of the name. Nowadays high-class women drop the "O" before their individual names, but add "Ko" after them. For instance, the name O Tama San would now be Tama-Ko San.

THE LADY OF THE PICTURE

Many years ago, long before the present prosaic era, there lived in Yedo a young man named Toshika. His family belonged to the aristocratic rank of the hatamoto samurai, those knights who possessed the right to march to battle directly under the Shogun's flag (hata), and his father was a high official in the Tokugawa Shogunate.

Toshika, whose disposition was of a dreamy and indolent nature with scholarly tastes, had no occupation.He took life easily, and when his studies were finished, he went to live at the family villa situated in the suburb of Aoyama.

Toshika was not interested in society, and except for an occasional visit to his home or to his favourite friend, he never went anywhere.Far from the world he spent his days quietly and pleasantly, reading books, tending and watering his flowers, practising the tea-ceremony, and composing poetry and playing on the flute.He was a young man of many accomplishments and studied art.He collected curios and specimens of well-known calligraphy, which all Japanese prize greatly, and he particularly delighted in pictures.

One day a certain friend whom Toshika had not seen for several months, came to call upon him.He had just returned from a visit to the seaport of Nagasaki and knowing the young man's tastes had brought with him, as a present, a Chinese drawing of a beautiful woman, which he begged Toshika to accept.

Toshika was very pleased with this acquisition to his treasures. He examined the painting carefully, and though he could find no signature of the artist, his knowledge of the subject told him that it was probably drawn by the well-known Chinese painter of the Shin era.

It was the portrait of a young woman in the prime of youth, and Toshika felt intuitively that it was a real likeness.The face was one of radiant loveliness, and the longer he gazed at it, the more the charm and fascination of it grew upon him.He carried it to his own room and hung it up in the alcove.Whenever he felt lonely he retired to the solitude of his chamber, and sat for hours before the drawing, looking at it and even addressing it.As the days went by, gradually the picture seemed to glow with life and Toshika began to think of it as a person.He wondered who the original of the portrait could have been, and said that he envied the artist who had been granted the happiness of looking upon her beauty.

Daily the figure seemed more alive and the face more exquisite, and Toshika, as he gazed in rapture upon it, longed to know its history.The haunting pathos of the expression and the speaking wistfulness of the dark soft eyes called to his heart like music and gave him no peace.

Toshika, in fact, became enamoured of the lovely image suspended in the alcove, and as the infatuation grew upon him he placed fresh flowers before it, changing them daily.At night he had his quilts[1] so arranged that the last thing he looked upon before closing his eyes in sleep was the lady of the picture.

Toshika had read many strange stories of the supernatural power of great artists.He knew that they were able to paint the minds of the originals into their portraits, whether of human beings or of creatures, so that through the spiritual force of the merit of their skill the pictures became endowed with life.

As the passion grew upon him the young lover believed that the spirit of the woman whom the portrait represented actually lived in the picture.As this thought formed itself in his mind he fancied that he could see the gentle rise and fall of her breast in breathing, and that her pretty lips, bright as the scarlet pomegranate bud, appeared to move as if about to speak to him.

One evening he was so filled with the sense of the reality of her presence that he sat down and composed a Chinese poem in praise of her beauty.

And the meaning of the high-flown diction ran something like this:

Thy beauty, sweet, is like the sun-flower:[2]

The crescent moon of three nights old thy arched brows:

Thy lips the cherry's dewy petals at flush of dawn:

Twin flakes of fresh-fallen snow thy dainty hands.

Blue-black, as raven's wing, thy clustering hair:

And as the sun half peers through rifts of cloud,

Gleams through thy robes the wonder of thy form.

Thy cheeks' dear freshness do bewilder me,

So pure, so delicate, rose-misted ivory:

And, like a sharp sword, pierce my breast

The glamour of thy dark eyes' messages

Ah, as I gaze upon thy pictured form

I feel therein thy spirit is enshrined,

Surely thou liv'st and know'st my love for thee!

The one who unawares so dear a gift bestowed

Was verily the gods' own messenger

And sent by Heaven to link our souls in one

'Tis sad that thou wert borne from thine own distant land

Far from thy race, and all who cherished thee;

Thy heart must lonely pine so far away,

In sooth thou need'st a mate to love and cherish thee.

But sorrow not, my picture love,

For Time's care-laden wings will never dim thy brow

From poisoned darts of Fate so placidly immune;

Anguish and grief will ne'er corrode thy heart,

And never will thy beauty suffer change:

While earthly beings wither and decay

Sickness and care will ever pass thee by,

For Art can grant where Love is impotent,

And dowers thee with immortality

Ah me!could the high gods but grant the prayer

Of my wild heart, and passionate desire!

Step down from out thy cloistered niche,

Step down from out thy picture on the wall!

My soul is thirsting for thy presence fair

To crown my days with rapture—be my wife!

How swift the winged hours would then pass by

In bliss complete, and lovers' ecstasy:

My life, dear queen, I dedicate to thee,

Ah!make it thus a thousand lives to me![3]

Toshika smiled to himself at the wild impossibility of his own chimera.Such a hope as he had breathed to her and to himself belonged to the realm of reverie, and not to the hard world of everyday life.Supposing that beautiful creature to have ever lived and the portrait to be a true likeness of her, she must have died ages ago, long before ever he was born.

However, having written the poem carefully, he placed it above the scroll and read it aloud, apostrophizing the lady of the picture.

It was the delicious season of spring, and Toshika sat with the sliding screens open to the garden.The fragrance of peach blossoms was wafted into the room by the breath of a gentle wind, and as the light of day faded into a soft twilight, over the quiet and secluded scene a crescent moon shed her tender jewel-bright radiance.

Toshika felt unaccountably happy, he could not tell why and sat alone, reading and thinking deep into the night.

Suddenly, in the stillness of the midnight, a rustle behind him in the alcove caused him to turn round quickly.

What was his breathless amazement to see that the picture had actually taken life.The beautiful woman he so much admired detached herself from the paper on which she was depicted, stepped down on to the mats, and came gliding lightly towards him.He scarcely dared to breathe.Nearer and nearer she approached till she knelt opposite to where he sat by his desk.Saluting him she bowed profoundly.

The ravishment of her beauty and her charm held him speechless.He could not but look at her, for she was lovelier than anyone he had ever seen.

At last she spoke, and her voice sounded to him like the low, clear notes of the nightingale warbling in the plum-blossom groves at twilight.

"I have come to thank you for your love and devotion.Such a useless, ugly[4] creature as myself ought not to be so audacious as to appear before you, but the virtue of your poem was irresistible and drew me forth. I was so moved by your sympathy that I felt I must tell you in person of my gratitude for all your care and thought of me. If you really think of me as you have written, let me stay with you always."

Toshika rejoiced greatly when he heard these words.He put out his hand and taking hers said, "Ever since you came here I have loved you dearly.Consent to be my wife and we shall be happy evermore.Tell me your name and who you are and where you come from."

She answered with a smile inexpressibly sweet, while the tears glistened in her eyes.

"My name is Shorei (Little Beauty).My father's name is Sai.He was descended from the famous Kinkei.We lived in China at a place called Kinyo.One day, when I was eighteen years of age, bandits came and made a raid on our village and, with other fair women, carried me away.Thus I was separated from my parents and never saw them more.For many months I was carried from place to place and led a wandering life.Then, alas!who could have foretold it, I was seized by bad men and sold into slavery.The sorrow, the anguish and the horror I suffered in my helpless misery and homesickness you can never know.I longed every hour of the day for some tidings of my parents, for even now, I do not know what became of them.One day an artist came to the house of my captivity and looking at all the women there, he praised my face and described me as the Moon among the Stars.And he painted my picture and showed it to all his friends.In that way I became famous, for everyone talked of my beauty and came to see me.But I could not bear my life, and being delicate, my unhappy lot and the uncertainty of my father's and mother's fate preyed upon my mind, so that I sickened and died in six months.This is the whole of my sad history.And now I have come to your country and to you.This must be because of a predestined affinity between us."

The young man's heart was filled with compassion as he listened to the sorrowful tale of the unfortunate woman, who had told him all her woes.

He felt that he loved her more than ever and that he must make up with his devotion for all the wretchedness she had suffered in the past.

They then began to compose poems together, and Toshika found that Shorei had had a literary education, that she was an adept in calligraphy and every kind of poetical composition.And his heart was filled with a great gladness that he had found a companion after his own heart.

They both became intensely interested in their poetical contest and as they composed they read their compositions aloud in turn, comparing and criticizing each other.At last, while Toshika was in the act of reciting a poem to Shorei, he suddenly awoke and found that he had been dreaming.

Unable to believe that his delightful experiences were but the memories of sleep he turned to the alcove.His cherished picture was hanging there and the lovely figure was limned as usual in living lines upon the paper.Was it all a delusion?As he watched the exquisite face before him, recalling with questioning wonder the events of the evening before, behold!the sweet mouth smiled at him, just as Shorei had smiled in his vision.Impatiently he waited for the darkness, hoping that sleep would again bring Shorei to his side.Night after night she came to him in his dreams, but of his happy adventure he spoke to none.He believed that in some miraculous way the power of poetry had evoked the spirit of the portrait.Centuries ago this ill-fated woman had lived and died an untimely death, and his love led her back to earth through the medium of an artist's skill and his own verse.Six months passed and Toshika desired nothing more in life than to possess Shorei as his bride for all the years to come.

When I was eighteen years of age, bandits ...made a raid on one village and ...carried me away.

He never dreamed of change, but at last, one night, Shorei came looking very sad.She sat by his desk as was her wont, but instead of conversing or composing she began to weep.

Toshika was very troubled, for he had never seen her in such a mood.

"Tell me," he said anxiously, "What is the matter?Are you not happy with me?"

"Ah, it is not that," answered Shorei, hiding her face in her sleeve and sobbing; "never have I dreamed of such happiness as you have given me.It is because we are so happy that I cannot bear the pain of separation for a single night.But I must now leave you, alas!Our affinity in this world has come to an end."

Toshika could hardly believe her words.He looked at her in great distress as he asked:

"Why must we part?You are my wife and I will never marry any other woman.Tell me why you speak of parting?"

"To-morrow you will understand," she answered mysteriously."We may meet no more now, but if you do not forget me I may see you again ere long."

Toshika had put out a hand and made as if to detain her, but she had risen and was gliding towards the alcove, and while he imploringly gazed at her she gradually faded from his sight and was gone.

Words cannot describe Toshika's despair.He felt that all the joy of life went with Shorei, and he could not endure the idea of living without her.

Slowly he opened his eyes and looked round the room.He heard the sparrows twittering on the roof, and in the light of dawn, as he thought, the night-lantern's flame dwindled to a fire-fly's spark.

He rose and rolled back the wooden storm-doors which shut the house in completely at night, and found that he had slept late, that the sun was already high in the heavens.

Listlessly he performed his toilet, listlessly he took his meal, and his old servants anxiously went about their work, fearing that their master was ill.

In the afternoon a friend came to call on Toshika.After exchanging the usual formalities on meeting, the visitor suddenly said:

"You are now of an age to marry.Will you not take a bride?I know of a lovely girl who would just suit you, and I have come to consult with you on the matter."

Toshika politely but firmly excused himself."Do not trouble yourself on my account, I pray you!I have not the slightest intention of marrying any woman at present, thank you," and he shook his head with determination.

The would-be go-between saw from the expression of Toshika's face that there was little hope in pressing his suit that day, so after a few commonplace remarks he took his leave and went home.

No sooner had the friend departed than Toshika's mother arrived.She, as usual, brought many gifts of things that she knew he liked, boxes of his favourite cakes and silk clothes for the spring season.Grateful for all her love and care, he thanked her affectionately and tried to appear bright and cheerful during her visit.But his heart was aching, and he could think of nothing but of the loss of Shorei, wondering if her farewell was final, or whether, as she vaguely hinted, she would come to him again.He said to himself that to hold her in his arms but once again he would gladly give the rest of his life.

His mother noticed his preoccupation and looked at him anxiously many times.At last she dropped her voice and said:

"Toshika, listen to me!Your father and I both think that you have arrived at an age when you ought to marry.You are our eldest son, and before we die we wish to see your son, and to feel sure that the family name will be carried on as it should be.We know of a beautiful girl who will make a perfect wife for you.She is the daughter of an old friend, and her parents are willing to give her to you.We only want your consent to the arrangement of the marriage."

Toshika, as his mother unfolded the object of her visit, understood the meaning of Shorei's warning, and said to himself:

"Ah, this is what Shorei meant—she foresaw my marriage, for she said that to-day I should understand; but she pledged herself at the same time to see me again—it is all very strange!"

Feeling that his fate was come upon him he consented to his mother's proposal.

She returned home delighted.She had had little doubt of her son's conformance to his parents' wishes, for he had always been of a tractable disposition.In anticipation, therefore, of his consent to the marriage, she had already bought the necessary betrothal presents, and the very next day these were exchanged between the two families.

Toshika, in the meantime, watched the picture day by day.This was his only consolation, for Shorei, his beloved, visited him no more in his dreams. His life was desolate without her and his heart yearned for her sweet presence.Had it not been for her promise to come to him again he knew that he would not care to live.He felt, however, that she still loved him and in some way or other would keep her promise to him, and for this waited.Of his approaching marriage he did not dare to think.He was a filial son, and knew that he must fulfil his duty to his parents and to the family.

When the bride was led into the room and seated opposite Toshika, what was his bewildering delight to see that she was ...the lady-love of his picture

As the days went by Toshika noticed that the picture lost by degrees its wonderful vitality.Slowly from the face the winning expression and from the figure the tints of life faded out, till at last the drawing became just like an ordinary picture.But he was left no time to pine over the mystery of the change, for a summons from his mother called him home to prepare for the marriage.He found the whole household teeming with the importance of the approaching event.At last the momentous day dawned.

His mother, proud of the product of her looms, set out in array his wedding robes, handwoven by herself.He donned them as in a dream, and then received the congratulations of his relatives and retainers and servants.

In those old days the bride and bridegroom never saw each other till the wedding ceremony.When the bride was led into the room and seated opposite Toshika, what was his bewildering delight to see that she was no stranger but the lady-love of his picture, the very same woman he had already taken to wife in his dream life.

And yet she was not quite the same, for when Toshika, a few days later, joyfully led her to his own home and compared her with the portrait, she was even ten times more beautiful.

[1] The floor of the Japanese room is padded with special grass mats over two inches thick. On these the bed quilts are laid out at night and packed away in cupboards in the daytime.

[2] Prumus Umé, or Plum blossom, the Japanese symbol of womanly virtue and beauty.

[3] Rendered into English verse by my friend, Countess Iso-ko-Mutsu.

[4] It is a Japanese custom for a woman to speak thus depreciatingly of herself.

Urasato's escape from the Yamana-Ya

URSATO, OR THE CROWN OF DAWN

THE POSITION AT THE OPENING OF THE STORY

Urasato and Tokijiro are lovers. The child, Midori, is born of this liaison. Tokijiro is a samurai in the service of a Daimyo, and has charge of his lord's treasure department. He is a careless young man of a wild-oat-sowing disposition, and while entirely absorbed in this love affair with Urasato, a valuable kakemono, one of the Daimyo's heirlooms, is stolen.The loss is discovered and Tokijiro, who is held responsible, dismissed.

To give Tokijiro the means of livelihood so that he may pursue the quest of the lost treasure, Urasato sells herself to a house of ill-fame, the Yamana-Ya by name, taking with her the child Midori, who is ignorant of her parentage. Kambei, the knave of a proprietor, is evidently a curio collector, and it is to be gathered from the context that the unfortunate young couple have some suspicion—afterwards justified—that by some means or other he has obtained possession of the kakemono—hence Urasato's choice of that particular house.

Tokijiro's one idea is to rescue Urasato, to whom he is devoted, but for lack of money he cannot visit her openly, and Kambei, seeing in him an unprofitable customer, and uneasy about the picture, for which he knows Tokijiro to be searching, forbade him the house, and persecutes Urasato and Midori to find out his whereabouts, in order, probably, that he may have him quietly put out of the way.

As in all these old love stories the hero is depicted as a weak character, for love of women was supposed to have an effeminizing and debasing effect on men and was greatly discouraged among the samurai by the feudal Daimyo of the martial provinces. On the other hand, the woman, though lost, having cast herself on the altar of what she considers her duty—the Moloch of Japan—often rises to sublime heights of heroism and self-abnegation, a paradox only found, it is said, in these social conditions of Japan. Urasato reminds one of the beautiful simile of the lotus that raises its head of dazzling bloom out of the slime of the pond—so tender are her sentiments, so strong and so faithful in character is she, in the midst of misery and horror.

This recitation, freely rendered into English from the chanted drama, tells the story of Urasato's incarceration, of the lover's stolen interviews, of the inadvertent finding of the picture, and of Urasato's and Midori's final escape from the dread Yamana-Ya.

URSATO, OR THE CROW OF DAWN[1]

The darkness was falling with the tender luminosity of an eastern twilight over the house; the sky was softly clouding, and a gentle wind sprang up and sighed through the pine-trees like a lullaby—the hush that comes at the end of the day with its promise of rest was over all the world, but in spite of the peaceful aspect of nature and of her surroundings, Urasato, as she came from her bath robed in crêpe and silken daintiness, felt very unhappy. To her world the night brought no peace or rest, only accumulated wretchedness and woe.

Midori, her little handmaid, followed her fair mistress upstairs, and as Urasato languidly pushed open the sliding screens of her room and sank upon the mats, Midori fetched the tobacco tray with its tiny lacquer chest and miniature brazier all aglow, and placed it by her side.

Urasato took up her little pipe, and with the weed of forgetfulness lulled for a while the pain of longing and loneliness which filled her heart.As she put the tobacco in the tiny pipe-bowl and smoked it in one or two whiffs and then refilled it again, the tap, tap of the pipe on the tray as she emptied the ashes were the only sounds, interluded with sighs that broke the stillness."Kachi," "Kachi," "Kachi" sounded the little pipe.

Tokijiro, waiting hopelessly outside the fence in the cold, could not so forget his misery.He kept in the shadow so as not to be seen by the other inmates of the house, for if he were discovered he would lose all chance of seeing Urasato that evening and, perhaps, for ever.What might happen if these secret visits were discovered he dared not think.To catch one glimpse of her he loved he had come far through the snow, and after losing his way and wandering about for hours, he now found himself outside the house, and waited, tired and cold and miserable, by the bamboo fence.

"Life," said Tokijiro, speaking to himself, "is full of change like a running stream. Some time ago I lost one of my lord's treasures, an old and valuable kakemono of a drawing of a garyobai (a plum-tree trained in the shape of a dragon). I ought to have taken more care of the property entrusted to me. I was accused of carelessness and dismissed. Secretly I am searching for it, but till now I have found no clue of the picture. I have even brought my troubles to Urasato, and made her unhappy about the lost treasure. Alas! I cannot bear to live longer. If I cannot see Urasato I will at least look upon little Midori's face once more and then take leave of this life for ever. The more I think, the more our mutual vows seem hopeless. My love for this imprisoned flower has become deeper and deeper, and now, alas! I cannot see her more. Such is this world of pain!"

While Tokijiro thus soliloquized outside in the snow, Urasato in the room was speaking to her child-attendant, Midori.

"Midori, tell me, are you sure no one saw my letter to Toki Sama yesterday?"

"You need have no anxiety about that, I gave it myself to Toki Sama,"[2] answered Midori.

"Hush," said Urasato, "you must not talk so loudly—some one might overhear you!"

"All right," whispered the little girl, obediently.Leaving Urasato's side she walked over to the balcony and looking down into the garden she caught sight of Tokijiro standing outside the fence.

"There, there!"exclaimed Midori, "there is Toki Sama outside the fence."

When Urasato heard these words joy filled her breast, a smile spread over her sad face, her languor vanished, and rising quickly from her seat on the mats, she glided to the balcony and placing her hands on the rail leaned far out so that she could see Tokijiro.

"Oh!Tokijiro San," she exclaimed, "you have come again at last, how glad I am to see you!"

Tokijiro, on hearing her voice calling him, looked up through the pine branches and the tears sprang to his eyes at sight of her, for into the depths of love their hearts sank always deeper and the two were fettered each to each with that bond of illusion which is stronger than the threat of hell or the promise of heaven.

"Oh!" said Urasato, sadly, "what can I have done in a former life that this should be insupportable without the sight of you? The desire to see you only increases in the darkness of love. At first, a tenderness, it spread through my whole being, and now I love—I love. The things I would tell you are as great in number as the teeth of my comb, but I cannot say them to you at this distance. When you are absent I must sleep alone, instead of your arm my hand the only pillow, while my pillow is wet with tears longing for you,—if only it were the pillow of Kantan[3] I could at least dream that you were by my side. Poor comfort 'tis for love to live on dreams!"

As she spoke, Urasato leaned far out over the balcony, the picture of youth, grace and beauty, her figure supple and fragile as a willow branch wafted to and fro by a summer breeze, and about her an air of the wistful sadness of the rains of early spring.

As she spoke, Urasato leaned far out over the balcony, the picture of youth, grace and beauty.

"Oh!Urasato!"said Tokijiro, sadly, "the longer I stay here the worse it will be for you.If we are discovered not only you, but Midori also will be punished, and as she does not know all how unhappy she will be, and what will you do then.Oh!misery!"

Urasato, overcome with the bitterness of their troubles and the hopelessness of their situation, and as if to shield Midori, impulsively drew the child to her and, embracing her with tenderness, burst into tears.

The sound of footsteps suddenly startled them both.Urasato straightened herself quickly, pushed the child from her, and wiped away her tears.Midori, always clever and quick-witted, rolled a piece of paper into a ball and threw it quickly over the fence.It was a pre-arranged signal of danger.Tokijiro understood and hid himself out of sight.The screen of the room was pushed aside and not the dreaded proprietor nor his shrew of a wife, but the kindly and indispensable hair-dresser, O[4] Tatsu, appeared.

"Oh, courtezan," said the woman, "I fear that I have kept you waiting.I wanted to come earlier, but I had so many customers that I could not get away before.As soon as I could do so I left and came to you ...but, Urasato Sama, what is the matter?You have a very troubled face and your eyes are wet with tears ...are you ill?Look here, Midori, you must take better care of her and give her some medicine."

"I wanted her to take some medicine," said Midori, "but she said she would not."

"I have always disliked medicine and, as Midori tells you, I refused to take any.I don't feel well to-day, O Tatsu.I don't know why, but I don't even wish to have the comb put through my hair—so I won't have my hair dressed now, O Tatsu, thank you."

"Oh," answered O Tatsu, "that is a pity—your hair needs putting straight—it is very untidy at the sides; let me comb it back and you will then feel better yourself, too—"

"O Tatsu," said Urasato, hopelessly; "you say so, but—even if the gloom that weighs down my spirit were lifted and my hair done up and put straight both would fall again, and knowing this, I am unhappy."

"Oh," replied O Tatsu, "the loosened hair-knot which troubles you is my work—come to the dressing-table ...come!"

Urasato could not well refuse the kindly woman and reluctantly allowed herself to be persuaded.She sat down in front of the mirror, but her heart was outside the fence with Tokijiro, and to wait till the woman had done her work was a torture to her.

"Listen to me," said O Tatsu, as she took her stand behind Urasato and with deft fingers put the disordered coiffure to rights, "people cannot understand the feelings of others unless they have themselves suffered the same conditions.Even I, in past times, was not quite as I am now.It seems foolish to speak of it, but I always feel for you.If you deign to listen to me I will tell you my story.Even such an ugly woman as I am—there is a proverb you know, that says 'Even a devil at eighteen is fascinating' (oni mo juhachi)—has had her day, and so there was someone who loved even me, and he is now my husband," and O Tatsu laughed softly, "ho-ho-ho." "Well, we plighted our vows and loved more and more deeply. At last he was in need of money and came to borrow of me, saying 'Lend me two bu!'[5] or 'Lend me three bu!' using me in those days only as his money-box. It must have been because our fate was determined in our previous life that I did not give him up. I let things go because I loved him. Youth does not come twice in a life-time. He was in great distress and I sold all my clothes to help him till my tansu[6] were empty, and then I filled them with his love letters. Things came to such a pass that we thought of committing suicide together. But a friend who knew what we were about to do stopped us, and so we are alive to this day. But things have changed since then, and now, when there is some small trouble, my husband tells me he will divorce me, and there are times when I feel I hate him and don't want to work for him any more. There is a proverb that 'the love of a thousand years can grow cold,' and it is true. Experience has taught me this."

O Tatsu ...took her stand behind Urasato and with deft fingers put the disordered coiffure to rights

"O Tatsu Sama," answered Urasato, "in spite of all you say, I have no one to love me in this wide world, such an unfortunate creature as I am, so devotedly as you loved him."

"You may think thus now," said O Tatsu, "for you have reached the age of love's prime. I know that people in love's despair often cut short their own lives, but while you have Midori to think of you cannot, you must not, commit suicide. Duty and love exist only while there is life. Oh dear, I have talked so much and so earnestly that I have forgotten to put in the tsuto-naoshi," and with the last finishing touches O Tatsu put in the pincer-like clasp which holds together the stray hair at the nape of the neck.

Urasato's eyes were dry, though her heart was full of sympathy and sorrow as she listened to O Tatsu's kind words of sympathy, and as a bedimmed mirror so was her soul clouded with grief.Midori, touched by the sad conversation, dropped tears as she flitted about over the mats, putting away the comb box here and a cushion straight there.

"Well," said O Tatsu, as she bowed to the ground and took her leave, "I am going yonder to the house of Adzumaya, good-bye!"and with these words she glided down the stairs and went out by the side door.Looking back as she did so, she called to Midori:

"Look here, Midori, I am going out by the side gate instead of by the kitchen—will you please fasten it after me."With these words she seized the astonished Tokijiro, who was hiding in the shadow, pushed him inside and shut the gate (pattari) with a snap.With an unmoved face as if nothing unusual had occurred, O Tatsu put up her umbrella, for snow had begun to fall, lighted her little lantern and pattered away across the grounds without once looking back.

Thus, through the compassionate help of another, Tokijiro was at last enabled to enter the house.He ran upstairs quickly, and entering the room, caught hold of Urasato's hand.

"Urasato!I cannot bear our lot any longer.I cannot bear to live away from you—at last I am able to tell you how I long to die with you since we cannot belong to each other any longer.But if we die together thus, what will become of poor little Midori.What misery—oh, what misery!No—no—I have it; you shall not die—I alone will die; but oh!Urasato, pray for the repose of my soul!"

"That would be too pitiless," said Urasato, while the tears fell like rain from her eyes, "if you die to-night what will become of our faithful little Midori and myself left behind?Let parents and child take hands to-night and cross the river of death together.We will not separate now, oh, no—no!Oh!Tokijiro San!you are too cruel to leave us behind."

Some one was now heard calling from below.

"Urasato Sama!Urasato Sama!"said a loud harsh voice, "come downstairs—you are wanted quickly, quickly—come!"

Then the sound of a woman's feet as she began to ascend the stairs reached the three inmates of the room.

Urasato's heart beat wildly and then seemed to stop with fright. Quick as a flash of lightning she hid Tokijiro in the kotatsu[7] and Midori, with her usual quick-wittedness, fetched the quilt and covered him over. Then she glided to the other side of the room. All this was the work of a moment.

"O Kaya San," said Urasato, "what is the matter?What are you making such a fuss about?What do you want with me now?"

"Oh!Urasato," answered the woman as she entered the room, "you pretend not to know why I call you.The master has sent for you—Midori is to come with you—such is his order!"

Urasato made no answer, but followed O Kaya, who had come to fetch her. Anxiety for Tokijiro hidden in the kotatsu, and fear concerning what the sudden summons might mean made her heart beat so that she knew not what to do.Both she and Midori felt that the woman was like a torturing devil driving them along so much against their will—they seemed to feel her fierce eyes piercing them through from behind.

O Kaya led them across the garden to another part of the house.The soft twilight had been succeeded by a dreary night.It was February and the night wind blew sharp and chill—the last snow of winter weighed down the bamboos; while, like an emblem of courage and strength in the midst of adversity, the odour of early plum blossoms hung upon the air.Overcome with anxiety, Urasato felt only the chill, and fear of the night spread through her whole being.She started and shivered when behind her Midori's clogs began to echo shrilly, like the voices of malicious wood-sprites in the trees laughing in derision at her plight.Her heart grew thin with pain and foreboding."Karakong," "karakong," sounded the clogs, as they scraped along."Ho, ho, ho!"mocked the echoing sprites from the bamboo wood.

They reached the veranda of the house on the other side of the quadrangle. O Kaya pushed open the shoji disclosing the grizzled-headed master, Kambei, seated beside the charcoal brazier looking fierce and angry. When Urasato and Midori saw him, their heart and soul went out with fear as a light in a sudden blast.

Urasato, however, calmed herself, and sitting down outside the room on the veranda, put her hands to the floor and bowed over them.The master turned and glared at her.

"Look here, Urasato," said he, "I have nothing but this to ask you.Has that young rascal Tokijiro asked you for anything out of this house—tell me at once—is such the case?I have heard so—tell me the truth!"

Urasato, frightened as she was, controlled herself and answered quietly:

"Such are the master's honourable words, but I have no remembrance of anyone asking me for anything whatsoever."

"Um," said the master, "I shan't get it out of you so easily I see," then turning to O Kaya, he said, "Here, O Kaya, do as I told you—tie her up to the tree in the garden and beat her till she confesses."

O Kaya rose from the mats and catching hold of the weeping Urasato dragged her up and untied and pulled off her girdle.The woman then carried the slender girl into the garden and bound her up with rope to a rough-barked, snow-covered pine-tree, which happened to be just opposite Urasato's room.O Kaya, lifting a bamboo broom threateningly, said, "Sa!Urasato, you won't be able to endure this—therefore make a true confession and save yourself.How can you be faithful to such a ghost of a rascal as Tokijiro?I have warned you many times, but in spite of all advice you still continue to meet him in secret.Your punishment has come at last—but it is not my fault, so please do not bear me any resentment.I have constantly asked the master to pardon you.To-night, out of pity, I begged him to let you off, but he would not listen.There is no help for it, I must obey my orders.Come, confess before you are beaten!"

So O Kaya scolded and entreated Urasato; but Urasato made no reply—she only wept and sobbed in silence.

"You are an obstinate girl!"said O Kaya, and she lifted the broom to strike.

Midori now rushed forward in an agony of distress and tried to ward off the blow about to fall on her beloved mistress.O Kaya flung the child away with her left arm, and bringing the broom down, began to beat Urasato mercilessly till her dress was disarranged and her hair fell down in disorder about her shoulders.

Midori could bear the sight no longer.She became frantic, and running to the wretched Kambei, lifted praying hands to him: then back again she darted to catch hold of O Kaya's dress, crying out to both: "Please, forgive her; oh, please, forgive her!Don't beat her so, I implore you!"

O Kaya, now fully exasperated, seized the sobbing child.

"I will punish you too," and tied Midori's hands behind her back.

Tokijiro, looking down from the balcony of Urasato's room, had been a distraught and helpless spectator of the whole scene of cruelty in the garden.He could now no longer restrain himself and was about to jump over the balcony to the rescue.But Urasato happened at that moment to look up and saw what he intended doing.She shook her head and managed to say, unheard by the others:

"Ah!this, for you to come out, no, no, no!"

Then, as O Kaya came back from tying up Midori, she quickly added to her, "No, I mean you who have tied up Midori, you must be pitying her, you must be, O Kaya San—but in the presence of the master for that reason it won't do!It won't do!"and here she spoke, purposely, incoherently to O Kaya, while she signed to Tokijiro with her eyes that he must not come out—that her words were meant for him under cover of being addressed to O Kaya.

Tokijiro knew that he could do nothing—he was utterly powerless to help Urasato, and if he obeyed his first impulse and jumped down into the garden he would only make matters a thousand times worse than they were, so he went back to the kotatsu, and bit the quilt and wept with impotent rage.

"She is suffering all this for my sake—oh!Urasato!oh!oh!oh!"

Kambei had now reached Urasato's side, and catching hold of her by the hair, said in a big voice, "Does not your heart tell you why you are so chastized? It is ridiculous that Tokijiro should come in search of the kakemono that was entrusted to me. Ha! you look surprised. You see I know all. Look! Isn't the picture hanging there in my room? I allow no one so much as to point a finger at it—Sa! Urasato, I am sure Tokijiro asked you to get him that—come—speak the truth now?"

"I have never been asked to steal any such thing," answered Urasato, sobbing.

"Oh, you obstinate woman—will nothing make you confess?Here, Midori—where is Tokijiro?Tell me that first?"

"I don't know," answered Midori.

"There is no reason why Midori should know what you ask," said Urasato, trying to shield the child.

"Midori is always with you," said Kambei—"and she must know," and turning to Midori he struck her, saying: "Now confess—where is Tokijiro hiding now?"

"Oh, oh, you hurt me," cried the child.

"Well, confess then," said the cruel man, "then I won't hurt you any more!"

"Oh ...Urasato," cried Midori, turning to her—"entreat the master to pardon me—if he kills me, before I die I can never meet my father whom I have never seen."

Tokijiro, upstairs in the balcony, heard all that was going on and murmured:

"That is, indeed, natural, poor child."

But Kambei, unaware that he was heard and seen, beat the child again and again.

"I can't make out what you say, little creature," he screamed with rage. "You shall feel the weight of this tekki[8] then we shall see if you will still not answer what is asked you."

Under this hell-like torture Midori could scarcely breathe.The poor child tried to crawl away, but as she was bound with rope, she was unable to do so.

The cruel man once more caught hold of her roughly by the shoulder and began to beat her again.At last the child gave a great cry of pain, lost consciousness, and fell back as though dead.

Kambei was now alarmed at what he had done, for he had no intention of killing the child—only of making her tell him where Tokijiro was living or hiding.He stopped beating her and stood on one side, angry enough at being thwarted by Urasato and Midori.

Urasato raised her head and moaned to herself as she looked at the prostrate child.

"I am really responsible for the child's suffering," she said to herself—"my sin is the cause of it all; forgive me, my child—you know it not, but I am your mother; and although you are only a child you have understood and helped me.You saw that I was in love and always anxious about my lover.This is from a fault in your former life that you have such a mother—ah!this is all, alas, fruit of our sins in another existence," and Urasato's tears flowed so fast that, like spring rain, they melted the snow upon which they fell.

O Kaya now came up to her, saying,

"What an obstinate creature you are! If you don't confess you shall wander in company with your child to the Meido,"[9] and with these words she raised her broom to strike.

Hikoroku, the clerk of the house, now came running upon the scene.He had fallen in love with Urasato and had often pressed his suit in vain.When he saw how matters stood he pushed O Kaya away.

"You are not to help Urasato!"screamed O Kaya, angrily.

"Go away, go away," said Hikoroku, "this punishment is the clerk's work—though I am only a humble servant, however humble I am I don't need your interference."

Then Hikoroku turned to Kambei and said apologetically.

"Excuse me, master, I have something to say to you; the matter is this—that dear Urasato—no, I mean Midori and Urasato—I never forget them, oh, no, no!I know their characters—they are good-hearted.This punishment is the clerk's work.If you will only leave Urasato to me I shall be able to make her confess.I am sure I can manage her.If you will make me responsible for making Urasato confess, I shall be grateful."

Kambei nodded his head, he was already tired, and said:

"Um—I would not allow anyone else to do this, but as I trust you Hikoroku, I will let you do it for a while; without fail you must make her confess, I will rest,"—and with these words he went into the house, intending to put the blame on Hikoroku if his regulation suffered because of his treatment of Urasato.

Hikoroku accompanied his master to the house and bowed low as he entered.He then came back to Urasato.

"Did you hear what the master said? Did he not say that he would not entrust this to anyone else but me—only to me—Hikoroku—don't you see what a fine fellow I am?If only you had listened to me before you need never have suffered so—I would have helped you, Urasato San!Perhaps you suspect me as being to blame for all this; but no—indeed, I am not—you and I are living in another world.Will you not listen to me—Urasato San?—but oh!—you have a different heart—oh!what am I to do?"and he placed his hands palm to palm and lifted them despairingly upwards to Urasato, shaking them up and down in supplication.

O Kaya had been listening to Hikoroku, for she was in love with him herself and was always jealous of the attention he paid to Urasato.She now came up and said, as she shrugged her shoulders from side to side: "Now Hikoroku Sama—what are you doing?What are you saying?Notwithstanding your promise to the master to make Urasato confess, you are now talking to her in this way.Whenever you see Urasato you always act like this without thinking of me or my feelings for you.I am offended—I can't help it!You will probably not get her to confess after all.Well—I will take your place, so go away!"

As O Kaya came up to Hikoroku he pushed her away, saying:

"No, never!You shall not hurt her—this is not your business—the master has entrusted it to me.As for you, it is ridiculous that you should love me.How ugly you are!Ugh!—your face is like a lion's.Are you not ashamed.Before the master I have no countenance left when I think of what you say to me.Now then—go away O Kaya—I am going to untie poor Urasato!"

O Kaya tried to push Hikoroku away.Hikoroku took up the broom and beat her without caring how much he hurt her.Mercilessly did he continue to beat her till she was overcome and, falling down on the snow, lay stunned for some time to come.

Having thus got rid of O Kaya, Hikoroku quickly released Urasato and Midori.As he lifted the child up she opened her eyes.

"Ya, ya!Are you still there, mother?"

Did Midori know that Urasato was her mother, or on returning to consciousness was it instinct or affection that made her use the tender name?

When she heard Midori's voice, Urasato felt that she must be in a dream, for she had feared that the child had been killed by Kambei's beating.

"Are you still alive?"she exclaimed, and caught the child in her arms while tears of joy fell down her pale cheeks.

Hikoroku looked on with a triumphant face, for he was pleased at what he had done.

"Urasato Sama, you must run away, and now that I have saved you both I can't stay here.I, too, shall be tied up and punished for this.I shall run away, too!Well, it is certainly better to escape with you than to remain here.Let us flee together now.Come with me.I must get my purse, however, before I go.Please wait here till I come back with my small savings—then I can help you; don't let anyone find you," and without waiting for Urasato's answer Hikoroku ran into the house.

Urasato and Midori stood clasping each other under the pine tree.They were shaking with cold and fatigue and pain.Suddenly a sound made them look up.Tokijiro suddenly stood before them.He had climbed out on to the roof, and walking round the quadrangle, had reached the spot where they stood and then let himself down by the pine-tree.When the two saw him they started for joy.

"Oh," said Urasato, scarcely able to make herself heard, "how did you get here, Tokijiro?"

"Hush," said Tokijiro, "don't speak so loudly. I have heard and seen all—oh! my poor Urasato, it has caused me much pain to think that you have suffered so much because of me; but in the midst of all this misery there is one thing over which we can rejoice. As soon as I heard what Kambei said about the kakemono I crept downstairs and into the room he pointed out, and there I found my lord's long-lost picture. Look, here it is! I have it safe at last. The very one drawn by Kanaoka. Someone must have stolen it. I am saved at last—I am thankful. I shall be received back into my lord's service—I owe this to you, and I shall never forget it as long as I live."

Footsteps were heard approaching, Tokijiro hid himself behind a post of the gate.He was only just in time.

Hikoroku came stumbling along across the garden from the other side of the house.

"Here, here, Urasato San, we can now fly together—I have got my money—we can get out by the gate.Wait another moment, I will steal in and get the picture for you."

As soon as Hikoroku had gone again Tokijiro rushed forward, and seizing Urasato and Midori by the hand, hurried them out of the garden.Once outside they felt that they had escaped from the horror and death of the tiger's mouth.

Hikoroku, not being able to find the picture, hastened back to the spot where he had left Urasato, when he ran into O Kaya, who had recovered consciousness, and now picked herself up from the ground somewhat bewildered and wondering what had happened.

"Are you Hikoroku?Are you Hikoroku?"she exclaimed, and caught him in her arms.

Catching sight of her face, Hikoroku cried out with disgust and horror.

"Ya!Avaunt evil!Avaunt devil!"

The three fugitives outside the gate heard Hikoroku's exclamation.Tokijiro caught up Midori and put her on his back.Then he and Urasato taking each other by the hand ran away as fast as they could.The dawn began to break and the birds to sing as they left the dread place behind them.From far and near the crows began to wing their way across the morning sky.

Hitherto the crow of dawn had parted them—it now united them. Thinking of this, Tokijiro and Urasato looked at each other with eyes brimming over with tears, yet shining with the light of new-born hope.

[1] The Crow of Dawn, or Akegarasu, another name for the story of Urasato. Akegarasu, literally rendered means "Dawn-Crow."It is an expression which typifies the wrench of parting at daybreak which lovers like Tokijiro and Urasato experience, when dawn comes heralded by the croak of a crow (karasu) flying across the half-lit sky—a sign that the time for the two to separate has come.