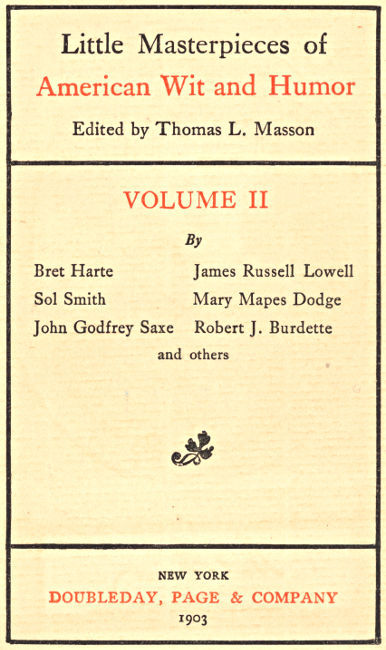

Little Masterpieces of American Wit and Humor, Volume II

Play Sample

By permission of Charles Scribner’s Sons

“What was it the aeronaut said when he fell out of his balloon and struck the earth with his usual dull thud?”

“He remarked that it was a hard world.”

JOHN TOWNSEND TROWBRIDGE

FRED TROVER’S LITTLE IRON-CLAD

Did I never tell you the story?Is it possible?Draw up your chair.Stick of wood, Harry.Smoke?

You’ve heard of my Uncle Popworth, though.Why, yes!You’ve seen him—the eminently respectable elderly gentleman who came one day last summer just as you were going; book under his arm, you remember; weed on his hat; dry smile on bland countenance; tall, lank individual in very seedy black.With him my tale begins; for if I had never indulged in an Uncle Popworth I should never have sported an Iron-clad.

Quite right, sir; his arrival was a surprise to me. To know how great a surprise, you must understand why I left city, friends, business, and settled down in this quiet village. It was chiefly, sir, to escape the fascinations of that worthy old gentleman that I bought this place, and took refuge here with my wife and little ones. Here we had respite, nepenthe from our memories of Uncle Popworth; here we used to sit down in the evening and talk of the past with grateful and tranquil emotions, as people speak of awful things endured in days that are no more. To us the height of human happiness was raising green corn and strawberries in a retired neighborhood where uncles were unknown. But, sir, when that Phantom, that Vampire, that Fate, loomed before my vision that day, if you had said, “Trover, I’ll give ye sixpence for this neat little box of yours,” I should have said, “Done!” with the trifling proviso that you should take my uncle in the bargain.

The matter with him?What, indeed, could invest human flesh with such terrors—what but this?he was—he is—let me shriek it in your ear—a bore—a BORE!of the most malignant type; an intolerable, terrible, unmitigated BORE!

That book under his arm was a volume of his own sermons—nine hundred and ninety-nine octavo pages, O Heaven!It wasn’t enough for him to preach and repreach those appalling discourses, but then the ruthless man must go and print ’em!When I consider what book-sellers—worthy men, no doubt, many of them, deserving well of their kind—he must have talked nearly into a state of syncope before ever he found one to give way, in a moment of weakness, of utter exhaustion and despair, and consent to publish him; and when I reflect what numbers of inoffensive persons, in the quiet walks of life, have been made to suffer the infliction of that Bore’s Own Book, I pause, I stand aghast at the inscrutability of Divine Providence.

Don’t think me profane, and don’t for a moment imagine I underrate the function of the preacher.There’s nothing better than a good sermon—one that puts new life into you.But what of a sermon that takes life out of you, instead of a spiritual fountain, a spiritual sponge that absorbs your powers of body and soul, so that the longer you listen the more you are impoverished?A merely poor sermon isn’t so bad; you will find, if you are the right kind of a hearer, that it will suggest something better than itself; a good hen will lay to a bit of earthen.But the discourse of your ministerial vampire, fastening by some mystical process upon the hearer who has life of his own—though not every one has that—sucks and sucks and sucks; and he is exhausted while the preacher is refreshed.So it happens that your born bore is never weary of his own boring; he thrives upon it; while he seems to be giving, he is mysteriously taking in—he is drinking your blood.

But you say nobody is obliged to read a sermon. O my unsophisticated friend! if a man will put his thoughts—or his words, if thoughts are lacking—between covers—spread his banquet, and respectfully invite Public Taste to partake of it, Public Taste being free to decline, then your observation is sound. If an author quietly buries himself in his book—very good! hic jacet: peace to his ashes!

as Macbeth observes, with some confusion of syntax, excusable in a person of his circumstances.Now, suppose they—or he—the man whose brains are out—goes about with his coffin under his arm, like my worthy uncle?and suppose he blandly, politely, relentlessly insists upon reading to you, out of that octavo sarcophagus, passages which in his opinion prove that he is not only not dead, but immortal?If such a man be a stranger, snub him; if a casual acquaintance, met in an evil hour, there is still hope—doors have locks, and there are two sides to a street, and nearsightedness is a blessing, and (as a last resort) buttons may be sacrificed (you remember Lamb’s story of Coleridge) and left in the clutch of the fatal fingers.But one of your own kindred, and very respectable, adding the claim of misfortune to his other claims upon you—pachydermatous to slights, smilingly persuasive, gently persistent—as imperturbable as a ship’s wooden figurehead through all the ups and downs of the voyage of life, and as insensible to cold water—in short, an uncle like my uncle, whom there was no getting rid of—what the deuce would you do?

Exactly; run away as I did.There was nothing else to be done, unless, indeed, I had throttled the old gentleman; in which case I am confident that one of our modern model juries would have brought in the popular verdict of justifiable insanity.But, being a peaceable man, I was averse to extreme measures.So I did the next best thing—consulted my wife, and retired to this village.

Then consider the shock to my feelings when I looked up that day and saw the enemy of our peace stalking into our little Paradise with his book under his arm and his carpet-bag in his hand!—coming with his sermons and his shirts, prepared to stay a week—that is to say a year—that is to say forever, if we would suffer him—and how was he to be hindered by any desperate measures short of burning the house down?

“My dear nephew!”says he, striding toward me with eager steps, as you perhaps remember, smiling his eternally dry, leathery smile—“Nephew Frederick!”—and he held out both hands to me, book in one and bag in t’other—“I am rejoiced!One would almost think you had tried to hide away from your old uncle, for I’ve been three days hunting you up.And how is Dolly?She ought to be glad to see me, after all the trouble I’ve had in finding you!And, Nephew Frederick—h’m!—can you lend me three dollars for the hackman?For I don’t happen to have——Thank you!I should have been saved this if you had only known I was stopping last night at a public house in the next village, for I know how delighted you would have been to drive over and fetch me!”

If you were not already out of hearing, you may have noticed that I made no reply to this affecting speech. The old gentleman has grown quite deaf of late years—an infirmity which was once a source of untold misery to his friends, to whom he was constantly appealing for their opinions, which they were obliged to shout in his ear. But now, happily, the world has about ceased responding to him, and he has almost ceased to expect responses from the world. He just catches your eye, and when he says, “Don’t you think so, sir?” or “What is your opinion, sir?” an approving nod does your business.

The hackman paid, my dear uncle accompanied me to the house, unfolding the catalogue of his woes by the way.For he is one of those worthy, unoffending persons whom an ungrateful world jostles and tramples upon—whom unmerciful disaster follows fast and follows faster.In his younger days he was settled over I don’t know how many different parishes; but secret enmity pursued him everywhere, poisoning the parochial mind against him, and driving him relentlessly from place to place.Then he relapsed into agencies, and went through a long list of them, each terminating in flat failure, to his ever-recurring surprise—the simple old soul never suspecting, to this day, who his one great tireless, terrible enemy is!

I got him into the library, and went to talk over this unexpected visit—or visitation—with Dolly.She bore up under it more cheerfully than could have been expected—suppressed a sigh—and said she would go down and meet him. She received him with a hospitable smile (I verily believe that more of the world’s hypocrisy proceeds from too much good-nature than from too little) and listened patiently to his explanations.

“You will observe that I have brought my bag,” says he, “for I knew you wouldn’t let me off for a day or two—though I must positively leave in a week—in two weeks, at the latest.I have brought my volume, too, for I am contemplating a new edition” (he is always contemplating a new edition, making that a pretext for lugging the book about with him), “and I wish to enjoy the advantages of your and Frederick’s criticism.I anticipate some good, comfortable, old-time talks over the old book, Frederick!”

We had invited some village friends to come in and eat strawberries and cream with us that afternoon; and the question arose, what should be done with the old gentleman? Harry, who is a lad of a rather lively fancy, coming in while we were taking advantage of his great-uncle’s deafness to discuss the subject in his presence, proposed a pleasant expedient. “Trot him out into the cornfield, introduce him to the scarecrow, and let him talk to that,” says he, grinning up into the visitor’s face, who grinned down at him, no doubt thinking what a wonderfully charming boy he was! If he were as blind as he is deaf, he might have been disposed of very comfortably in some such ingenious way—the scarecrow, or any other lay figure, might have served to engage him in one of his immortal monologues.As it was, the suggestion bore fruit later, as you will see.

While we were consulting—keeping up our scattering fire of small-arms under the old talker’s heavy guns—our parish minister called,—old Doctor Wortleby, for whom we have a great liking and respect.Of course we had to introduce him to Uncle Popworth—for they met face to face; and of course Uncle Popworth fastened at once upon the brother clergyman.Being my guest, Wortleby could do no less than listen to Popworth, who is my uncle.He listened with interest and sympathy for the first half hour; and then continued listening for another half hour, after his interest and sympathy were exhausted.Then, attempting to go, he got his hat, and sat with it in his hand half an hour longer.Then he stood half an hour on his poor old gouty feet, desperately edging toward the door.

“Ah, certainly,” says he, with a weary smile, repeatedly endeavoring to break the spell that bound him.“I shall be most happy to hear the conclusion of your remarks at some future time” (even ministers can lie out of politeness); “but just now—”

“One word more, and I am done,” cries my Uncle Popworth, for the fiftieth time; and Wortleby, in despair, sat down again.

Then our friends arrived.

Dolly and I, who had all the while been benevolently wishing Wortleby would go, and trying to help him off, now selfishly hoped he would remain and share our entertainment—and our Uncle Popworth.

“I ought to have gone two hours ago,” he said, with a plaintive smile, in reply to our invitation; “but, really, I am feeling the need of a cup of tea” (and no wonder!)“and I think I will stay.”

We cruelly wished that he might continue to engage my uncle in conversation; but that would have been too much to hope from the sublime endurance of a martyr—if ever there was one more patient than he.Seeing the Lintons and the Greggs arrive, he craftily awaited his opportunity, and slipped off, to give them a turn on the gridiron.First Linton was secured; and you should have seen him roll his mute, appealing orbs, as he settled helplessly down under the infliction.Suddenly he made a dash.“I am ignorant of these matters,” said he; “but Gregg understands them—Gregg will talk with you.”But Gregg took refuge behind the ladies.The ladies, receiving a hint from poor distressed Dolly, scattered.But no artifice availed against the dreadful man.Piazza, parlor, garden—he ranged everywhere, and was sure to seize a victim.

At last tea was ready, and we all went inThe Lintons and Greggs were people of the world, who would hardly have cared to wait for a blessing on such lovely heaps of strawberries, in mugs of cream they saw before them; but, there being two clergymen at the table, the ceremony was evidently expected.We were placidly seated; there was a hush, agreeably filled with the fragrance of the delicious fruit; even my Uncle Popworth, from long habit, turned off his talk at that suggestive moment; when I did what I thought a shrewd thing.I knew too well my relative’s long-windedness at his devotions, as at everything else.(I wonder if Heaven itself isn’t bored by such fellows!)I had suffered, I had seen my guests suffer, too much from him already—to think of deliberately yielding him a fearful advantage over us; so I coolly passed him by, and gave an expressive nod to the old Doctor.

Wortleby began; and I was congratulating myself on my adroit management of a delicate matter, when—conceive my consternation!—Popworth—not to speak it profanely—followed suit!The reverend egotist couldn’t take in the possibility of anybody but himself being invited to say grace at our table, he being present—he hadn’t noticed my nod to the Doctor, and the Doctor’s low, earnest voice didn’t reach him—and there, with one blessing going on one side of the table, he, as I said, pitched in on the other!His eyes shut, his hands spread over his plate, his elbows on the board, his head bowed, he took care that grace should abound with us for once!His mill started, I knew there was no stopping it, and I hoped Wortleby would desist.But he didn’t know his man.He seemed to feel that he had the stroke-car, and he pulled away manfully.As Popworth lifted up his loud, nasal voice, the old Doctor raised his voice, in the vain hope, I suppose, of making himself heard by his lusty competitor.If you have never had two blessings running opposition at your table, in the presence of invited guests, you can never imagine how astounding, how killingly ludicrous it was!I felt that both Linton and Gregg were ready to tumble over, each in an apoplexy of suppressed emotions; while I had recourse to my handkerchief to hide my tears.At length, poor Wortleby yielded to fate—withdrew from the unequal contest—hauled off—for repairs, and the old seventy-two gun-ship thundered away in triumph.

At last (as there must be an end to everything under the sun) my uncle came to a close; and a moment of awful silence ensued, during which no man durst look at another.But in my weak and jelly-like condition I ventured a glance at him, and noticed that he looked up and around with an air of satisfaction at having performed a solemn duty in a becoming manner, blissfully unconscious of having run a poor brother off the track.Seeing us all with moist eyes and much affected—two or three handkerchiefs still going—he no doubt flattered himself that the pathetic touches in his prayer had told.

This will give you some idea of the kind of man we had on our hands; and I won’t risk making myself as great a bore as he is, by attempting a history of his stay with us; for I remember I set out to tell you about my little Iron-clad.I’m coming to that.

Suffice it to say, he stayed—he stayed—he stayed!—five mortal weeks; refusing to take hints when they almost became kicks; driving our friends from us, and ourselves almost to distraction; his misfortunes alone protecting him from a prompt and vigorous elimination; when a happy chance helped me to a solution of this awful problem of destiny.

More than once I had recalled Harry’s vivacious suggestion of the scarecrow—if one could only have been invented that would sit composedly in a chair and nod when spoken to!I was wishing for some such automaton, to bear the brunt of the boring with which we were afflicted, when one day there came a little man into the garden, where I had taken refuge.

He was a short, swarthy, foreign looking, diminutive, stiff, rather comical fellow—little figure mostly head, little head mostly face, little face mostly nose, which was by no means little—a sort of human vegetable (to my horticultural eye) running marvelously to seed in that organ.The first thing I saw, on looking up at the sound of footsteps, was the said nose coming toward me, among the sweet-corn tassels.Nose of a decidedly Hebraic cast—the bearer respectably dressed, though his linen had an unwholesome sallowness, and his cloth a shiny, much-brushed, second-hand appearance.

Without a word he walks up to me, bows solemnly, and pulls from his pocket (I thought he was laying his hand on his heart) the familiar, much-worn weapon of his class—the folded, torn yellow paper, ready to fall to pieces as you open it—in short, the respectable beggar’s certificate of character.With another bow (which gave his nose the aspect of the beak of a bird of prey making a pick at me) he handed me the document.I found that it was dated in Milwaukee, and signed by the mayor of that city, two physicians, three clergymen, and an editor, who bore united testimony to the fact that Jacob Menzel—I think that was his name—the bearer, anyway—was a deaf mute, and, considering that fact, a prodigy of learning, being master of no less than five different languages (a pathetic circumstance, considering that he was unable to speak one); moreover, that he was a converted Jew; and, furthermore, a native of Germany, who had come to this country in company with two brothers, both of whom had died of cholera in St.Louis in one day; in consequence of which affliction, and his recent conversion, he was now anxious to return to the Fatherland, where he proposed to devote his life to the conversion of his brethren—the upshot of all which was that good Christians and charitable souls everywhere were earnestly recommended to aid the said Jacob Menzel in his pious undertaking.

I was fumbling in my pocket for a little change wherewith to dismiss him—for that is usually the easiest way of getting off your premises and your conscience the applicant for “aid,” who is probably an impostor, yet possibly not—when my eye caught the words (for I still held the document), “would be glad of any employment which may help to pay his way.”The idea of finding employment for a man of such a large nose and little body, such extensive knowledge and diminutive legs—who had mastered five languages yet could not speak or understand a word of any one of them, struck me as rather pleasant, to say the least; yet, after a moment’s reflection—wasn’t he the very thing I wanted, the manikin, the target for my uncle?

Meanwhile he was scribbling rapidly on a small slate he had taken from his pocket.With another bow (as if he had written something wrong and was going to wipe it out with his nose), he handed me the slate, on which I found written in a neat hand half a dozen lines in as many different languages—English, Latin, Hebrew, German, French, Greek—each, as far as I could make out, conveying the cheerful information that he could communicate with me in that particular tongue. I tried him in English, French and Latin, and I must acknowledge that he stood the test; he then tried me in Greek and Hebrew, and I as freely confess that I didn’t stand the test. He smiled intelligently, nodded, and condescendingly returned to the English tongue, writing quickly, “I am a poor exile from Fatherland, and I much need friends.”

I wrote: “You wish employment?”

He replied: “I shall be much obliged for any service I shall be capable to do,” and passed me the slate with a hopeful smile.

“What can you do?”I asked.

He answered: “I copy the manuscripts, I translate from the one language to others with some perfect exactitude, I arrange the libraries, I make the catalogues, I am capable to be any secretary.”And he looked up as if he saw in my eyes a vast vista of catalogues, manuscripts, libraries, and Fatherland at the end of it.

“How would you like to be companion to a literary man?”I inquired.

He nodded expressively, and wrote: “I should that like over all.But I speak and hear not.”

“No matter,” I replied.“You will only have to sit and appear to listen, and nod occasionally.”

“You shall be the gentleman?”he asked, with a bright, pleased look.

I explained to him that the gentleman was an unfortunate connection of my family, whom we could not regard as being quite in his right mind.

Jacob Menzel smiled, and touched his forehead interrogatively.

I nodded, adding on the slate, “He is perfectly harmless, but he can only be kept quiet by having some person to talk and read to.He will talk and read to you.He must not know you are deaf.He is very deaf himself, and will not expect you to reply.”And, for a person wishing a light and easy employment, I recommended the situation.

He wrote at once, “How much you pay?”

“One dollar a day, and board you,” I replied.

He of the nose nodded eagerly at that, and wrote, “Also you make to be washed my shirt?”

I agreed; and the bargain was closed.I got him into the house, and gave him a bath, a clean shirt, and complete instructions how to act.

The gravity with which he entered upon the situation was astonishing.He didn’t seem to taste the slightest flavor of a joke in it at all.It was a simple matter of business; he saw in it only money and Fatherland.

Meanwhile I explained my intentions to Dolly, saying in great glee: “His deafness is his defense: the old three-decker may bang away at him; he is iron-clad!”And that suggested the name we have called him by ever since.

When he was ready for action, I took him in tow, and ran him in to draw the Popworth’s fire—in other words, introduced him to my uncle in the library.The meeting of my tall, lank relative and the big-nosed little Jew was a spectacle to cure a hypochondriac!“Mr. Jacob Menzel—gentleman from Germany—traveling in this country,” I yelled in the old fellow’s ear.He of the diminutive legs and stupendous nose bowed with perfect decorum, and seated himself, stiff and erect, in the big chair I placed for him.The avuncular countenance lighted up; here were fresh woods and pastures new to that ancient shepherd.As for myself, I was well nigh strangled by a cough which just then seized me, and obliged to retreat—for I never was much of an actor, and the comedy of that first interview was overpowering.

As I passed the dining-room door, Dolly, who was behind it, gave my arm a fearful pinch that answered, I suppose, in the place of a scream, as a safety-valve for her hysterical emotions.“Oh, you cruel man—you miserable humbug!”says she; and went off into convulsions of laughter.The door was open, and we could see and hear everything.

“You are traveling, h’m?”says my uncle.The nose nodded duly.“H’m!I have traveled, myself,” the old gentleman proceeded; “my life has been one of vicissitudes, h’m!I have journeyed, I have preached, I have published—perhaps you have heard of my literary venture”—and over went the big volume to the little man, who took it, turned the leaves, and nodded and smiled, according to instructions.

“You are very kind to say so; thank you!” says my uncle, rubbing his husky hands with satisfaction. “Rejoiced to meet with you! It is always a gratification to have an intelligent and sympathizing brother to open one’s mind to; it is especially refreshing to me, for, as I may say without egotism, my life and labors have not been appreciated.”

From that the old interminable story took its start and flowed on, the faithful nose nodding assent at every turn in that winding stream.

The children came in for their share of the fun; and for the first time in our lives we took pleasure in the old gentleman’s narration of his varied experiences.

“Oh, hear him!See him go it!”said Robbie.“What a nose!”

“Long may it wave!”said Harry.

With other remarks of a like genial nature; while there they sat, the two—my uncle on one side, long, lathy, self-satisfied, gesticulating, earnestly laying his case before a grave jury of one, whom he was bound to convince, if time would allow; my little Jew facing him, upright in his chair, stiff, imperturbable, devoted to business, honorably earning his money, the nose in the air, immovable, except when it played duly up and down at fitting intervals; in which edifying employment I left them and went about my business, a cheerier man.

Ah, what a relief it was to feel myself free for a season from the attacks of the enemy—to know that my plucky little Iron-clad was engaging him!In an hour I passed through the hall again, heard the loud, blatant voice still discoursing (it had got as far as the difficulties with the second parish), and saw the unflinching nasal organ perform its graceful seesaw of assent.An hour later it was the same—except that the speaker had arrived at the persecutions which drove him from parish number three.When I went to call them to dinner, the scene had changed a little, for now the old gentleman, pounding the table for a pulpit, was reading aloud passages from a powerful farewell sermon preached to his ungrateful parishioners.I was sorry I couldn’t give my man a hint to use his handkerchief at the affecting periods, for the nose can hardly be called a sympathetic feature (unless, indeed, you blow it), and these nods were becoming rather too mechanical, except when the old gentleman switched off on the argumentative track, as he frequently did.“What think you of that?”he would pause in his reading to inquire.“Isn’t that logic?Isn’t that unanswerable?”In responding to which appeals nobody could have done better than my serious, my devoted, my lovely little Jew.

“Dinner!”I shouted over my uncle’s dickey.It was almost the only word that had the magic in it to rouse him from the feast of reason which his own conversation was to him. It was always easy to head him toward the dining-room—to steer him into port for necessary supplies. The little Iron-clad followed in his wake. At table the old gentleman resumed the account of his dealings with parish number three, and got on as far as negotiations with number four; occasionally stopping to eat his soup or roast beef very fast; at which time Jacob Menzel, who was very much absorbed in his dinner, but never permitted himself to neglect business for pleasure, paused at the proper intervals, with his spoon or fork half-way to his mouth, and nodded—just as if my uncle had been speaking—yielding assent to his last remarks after mature consideration, no doubt the old gentleman thought.

The fun of the thing wore off after awhile, and then we experienced the solid advantages of having an Iron-clad in the house.Afternoon—evening—the next day—my little man of business performed his function promptly and assiduously.But in the afternoon of the second day he began to change perceptibly.He wore an aspect of languor and melancholy that alarmed me.The next morning he was pale, and went to his work with an air of sorrowful resignation.

“He is thinking of Fatherland,” said the sympathizing Dolly; while Harry’s less-refined but more sprightly comment was, that the nose had about played out.

Indeed, it had almost ceased to wave; and I feared that I was about to lose a most valuable servant, whose place it would be impossible to fill.Accordingly, I wrote on a slip of paper, which I sent in to him:

“You have done well, and I raise your salary to a dollar and a quarter a day.Your influence over our unfortunate relative is soothing and beneficial.Go on as you have begun and merit the lasting gratitude of an afflicted family.”

That seemed to cheer him a little—to wind him up, as Harry said, and set the pendulum swinging again.But it was not long before the listlessness and low spirits returned; Menzel showed a sad tendency to shirk his duty; and before noon there came a crash.

I was in the garden, when I heard a shriek of rage and despair, and saw the little Jew coming toward me with frantic gestures.

“I yielt!I abandone!I take my moneys and my shirt, and I go!”says he.

I stood in perfect astonishment at hearing the dumb speak; while he threw his arms wildly above his head, exclaiming:

“I am not teaf!I am not teaf!I am not teaf!He is one terreeble mon!He vill haf my life!So I go—I fly—I take my moneys and my shirt—I leafe him, I leafe your house!I vould earn honest living, but—Gott im himmel!Dieu des dieux! All de devils!” he shrieked, mixing up several of his languages at once, in his violent mental agitation.

“Jacob Menzel!”said I solemnly, “I little thought I was having to do with an impostor!”

“If I haf you deceive, I haf myself more dan punish!”was his reply.“Now I resign de position.I ask for de moneys and de shirt, and I part!”

Just then my uncle came up, amazed at his new friend’s sudden revolt and flight, and anxious to finish up with his seventh parish.

“I vill hear no more of your six, of your seven—I know not how many parish!”screamed the furious little Jew, turning on him.

“What means all this?”said my bewildered uncle.

“I tell you vat means it all!”the vindictive little impostor, tiptoeing up to him, yelled at his cheek.“I make not vell my affairs in your country; I vould return to Faderlant; for conwenience I carry dis pappeer.I come here; I am suppose teaf; I accept de position to be your companion, for if a man hear, you kill him tead soon vid your book and your ten, twenty parish!I hear!You kill me!and I go!”

And, having obtained his “moneys” and his shirt, he went. That is the last I ever saw of my little Iron-clad. I remember him with gratitude, for he did me good service, and he had but one fault, namely, that he was not iron-clad!

As for my uncle, for the first time in his life, I think, he said never a word, but stalked into the house.Dolly soon came running out to ask what was the matter; Popworth was actually packing his carpet-bag!I called Andrew, and ordered him to be in readiness with the buggy to take the old gentleman over to the railroad.

“What!going?”I cried, as my uncle presently appeared, bearing his book and his baggage.

“Nephew Frederick,” said he, “after this treatment, can you ask me if I am going?”

“Really,” I shouted, “it is not my fault that the fellow proved an impostor.I employed him with the best of intentions, for your—and our—good!”

“Nephew Frederick,” said he, “this is insufferable; you will regret it!I shall never—never“ (as if he had been pronouncing my doom) “accept of your hospitalities again!”

He did, however, accept some money which I offered him, and likewise a seat in the buggy.I watched his departure with joy and terror—for at any moment he might relent and stay; nor was I at ease in my mind until I saw Andrew come riding back alone.

We have never seen the old gentleman since.But last winter I received a letter from him; he wrote in a forgiving tone, to inform me that he had been appointed chaplain in a prison, and to ask for a loan of money to buy a suit of clothes.I sent him fifty dollars and my congratulations.I consider him eminently qualified to fill the new situation.As a hardship, he can’t be beat; and what are the rogues sent to prison for but to suffer punishment?

Yes, it would be a joke if my little Iron-clad should end his career of imposture in that public institution, and sit once more under my excellent uncle!But I can’t wish him any such misfortune.His mission to us was one of mercy.The place has been Paradise again, ever since his visit.—Scribner’s Magazine, August, 1873.

A BOSTON LULLABY

ROBERT JONES BURDETTE

THE ARTLESS PRATTLE OF CHILDHOOD

We always did pity a man who does not love childhood.There is something morally wrong with such a man.If his tenderest sympathies are not awakened by their innocent prattle, if his heart does not echo their merry laughter, if his whole nature does not reach out in ardent longing after their pure thoughts and unselfish impulses, he is a sour, crusty, crabbed old stick, and the world full of children has no use for him.In every age and clime the best and noblest men loved children.Even wicked men have a tender spot left in their hardened hearts for little children.The great men of the earth love them.Dogs love them.Kamehame Kemokimodahroah, the King of the Cannibal Islands, loves them.Rare and no gravy.Ah, yes, we all love children.

And what a pleasure it is to talk with them!Who can chatter with a bright-eyed, rosy-cheeked, quick-witted little darling, anywhere from three to five years, and not appreciate the pride which swells a mother’s breast when she sees her little ones admired?Ah, yes, to be sure.

One day—ah, can we ever cease to remember that dreamy, idle, summer afternoon—a lady friend, who was down in the city on a shopping excursion, came into the sanctum with her little son, a dear little tid-toddler of five bright summers, and begged us to amuse him while she pursued the duties which called her down-town.Such a bright boy; so delightful it was to talk to him.We can never forget the blissful half-hour we spent booking that prodigy up in his centennial history.

“Now, listen, Clary,” we said—his name was Clarence Fitzherbert Alencon de Marchemont Caruthers—“and learn about George Washington.”

“Who’s he?”inquired Clarence, etc.

“Listen,” we said; “he was the father of his country.”

“Whose country?”

“Ours—yours and mine; the confederated union of the American people, cemented with the life-blood of the men of ’76 poured out upon the altars of our country as the dearest libation to liberty that her votaries can offer.”

“Who did?”asked Clarence.

There is a peculiar tact in talking to children that very few people possess.Now, most people would have grown impatient and lost their temper, when little Clarence asked so many irrelevant questions, but we did not.We knew that, however careless he might appear at first, we could soon interest him in the story, and he would be all eyes and ears.So we smiled sweetly—that same sweet smile which you may have noticed on our photographs.Just the faintest ripple of a smile breaking across the face like a ray of sunlight, and checked by lines of tender sadness just before the two ends of it pass each other at the back of the neck.

And so, smiling, we went on.

“Well, one day George’s father——”

“George who?”asked Clarence.

“George Washington.He was a little boy then, just like you.One day his father——”

“Whose father?”demanded Clarence, with an encouraging expression of interest.

“George Washington’s—this great man we were telling you of.One day George Washington’s father gave him a little hatchet for a——”

“Gave who a little hatchet?”the dear child interrupted with a gleam of bewitching intelligence.Most men would have betrayed signs of impatience, but we didn’t.We know how to talk to children, so we went on.

“George Washington.His——”

“Who gave him the little hatchet?”

“His father.And his father——”

“Whose father?”

“George Washington’s.”

“Oh!”

“Yes, George Washington.And his father told him——”

“Told who?”

“Told George.”

“Oh, yes, George.”

And we went on, just as patient and as pleasant as you could imagine.We took up the story right where the boy interrupted; for we could see that he was just crazy to hear the end of it.We said:

“And he told him that——”

“Who told him what?”Clarence broke in.

“Why, George’s father told George.”

“What did he tell him?”

“Why, that’s just what I’m going to tell you.He told him——”

“Who told him?”

“George’s father.He——”

“What for?”

“Why, so he wouldn’t do what he told him not to do.He told him——”

“George told him?”queried Clarence.

“No, his father told George——”

“Oh!”

“Yes; told him that he must be careful with the hatchet——”

“Who must be careful?”

“George must.”

“Oh!”

“Yes; must be careful with the hatchet——”

“What hatchet?”

“Why, George’s.”

“Oh!”

“Yes; with the hatchet, and not cut himself with it, or drop it in the cistern, or leave it out in the grass all night.So George went round cutting everything he could reach with his hatchet.At last he came to a splendid apple tree, his father’s favorite, and cut it down and——”

“Who cut it down?”

“George did.”

“Oh!”

“—but his father came home and saw it the first thing, and——”

“Saw the hatchet?”

“No; saw the apple tree.And he said, ‘Who has cut down my favorite apple tree?’”

“What apple tree?”

“George’s father’s.And everybody said they didn’t know anything about it, and——”

“Anything about what?”

“The apple tree.”

“Oh!”

“—and George came up and heard them talking about it——”

“Heard who talking about it?”

“Heard his father and the men.”

“What was they talking about?”

“About this apple tree.”

“What apple tree?”

“The favorite apple tree that George cut down.”

“George who?”

“George Washington.”

“Oh!”

“So George came up and heard them talking about it, and he——”

“What did he cut it down for?”

“Just to try his little hatchet.”

“Whose little hatchet?”

“Why, his own; the one his father gave him.”

“Gave who?”

“Why, George Washington.”

“Who gave it to him?”

“His father did.”

“Oh!”

“So George came up and he said, ‘Father, I cannot tell a lie.I——’”

“Who couldn’t tell a lie?”

“Why, George Washington.He said, ‘Father, I cannot tell a lie.It was——’”

“His father couldn’t?”

“Why, no; George couldn’t.”

“Oh, George?Oh, yes.”

“‘—it was I cut down your apple tree.I did——’”

“His father did?”

“No, no.It was George said this.”

“Said he cut his father?”

“No, no, no; said he cut down his apple tree.”

“George’s apple tree?”

“No, no; his father’s.”

“Oh!”

“He said——”

“His father said?”

“No, no, no; George said, ‘Father, I cannot tell a lie.I did it with my little hatchet.’And his father said, ‘Noble boy, I would rather lose a thousand trees than have you tell a lie.’”

“George did?”

“No; his father said that.”

“Said he’d rather have a thousand apple trees?”

“No, no, no; said he’d rather lose a thousand apple trees than——”

“Said he’d rather George would?”

“No; said he’d rather he would than have him lie.”

“Oh, George would rather have his father lie?”

We are patient, and we love children, but if Mrs. Caruthers, of Arch Street, hadn’t come and got her prodigy at this critical juncture, we don’t believe all Burlington could have pulled us out of that snarl.And as Clarence Fitzherbert Alencon de Marchemont Caruthers patted down the stairs, we heard him telling his ma about a boy who had a father named George, and he told him to cut down an apple tree, and he said he’d rather tell a thousand lies than cut down one apple tree.

In the House of Representatives one day Mr. Springer was finishing an argument and ended by saying, “I am right, I know I am; and I would rather be right than be President.”He stood near the late S.S.Cox, who looked mischievously across at him and said as he ended, “Don’t worry about that, Springer; you’ll never be either.”

THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT

The late Mr. William R.Travers liked Bermuda enormously, but it would seem that he found its comforts not altogether unalloyed.A friend who once visited him there was congratulating him on his improved appearance.

“This is a grand place for change and rest,” said his friend.“Just what you needed.”

“Yes,” replied Mr. Travers, sadly.“Th-th-this is a magn-ni-ni-nif-ficent place f-f-f-for b-b-both.The ni-ni-niggers look out f-f-f-for the ch-ch-ch-change, and the hotel ke-ke-keepers take th-th-the rest.”

[ANONYMOUS]

ST.PETER AT THE GATE

HENRY GUY CARLETON

THE THOMPSON STREET POKER CLUB

SOME CURIOUS POINTS IN THE NOBLE GAME UNFOLDED

When Mr. Tooter Williams entered the gilded halls of the Thompson Street Poker Club Saturday evening it was evident that fortune had smeared him with prosperity.He wore a straw hat with a blue ribbon, an expression of serene content, and a glass amethyst on his third finger whose effulgence irradiated the whole room and made the envious eyes of Mr. Cyanide Whiffles stand out like a crab’s.Besides these extraordinary furbishments, Mr. Williams had his mustache waxed to fine points and his back hair was precious with the luster and richness which accompany the use of the attar of Third Avenue roses combined with the bear’s grease dispensed by basement barbers on that fashionable thoroughfare.

In sharp contrast to this scintillating entrance was the coming of the Reverend Mr. Thankful Smith, who had been disheveled by the heat, discolored by a dusty evangelical trip to Coney Island, and oppressed by an attack of malaria which made his eyes bloodshot and enriched his respiration with occasional hiccoughs and that steady aroma which is said to dwell in Weehawken breweries.

The game began at eight o’clock, and by nine and a series of two-pair hands and bull luck Mr. Gus Johnson was seven dollars and a nickel ahead of the game, and the Reverend Mr. Thankful Smith, who was banking, was nine stacks of chips and a dollar bill on the wrong side of the ledger.Mr. Cyanide Whiffles was cheerful as a cricket over four winnings amounting to sixty-nine cents; Professor Brick was calm, and Mr. Tooter Williams was gorgeous and hopeful, and laying low for the first jackpot, which now came.It was Mr. Whiffles’s deal, and feeling that the eyes of the world were upon him, he passed around the cards with a precision and rapidity which were more to his credit than the I.O.U.from Mr. Williams which was left over from the previous meeting.

Professor Brick had nine high and declared his inability to make an opening.

Mr. Williams noticed a dangerous light come into the Reverend Mr. Smith’s eye and hesitated a moment, but having two black jacks and a pair of trays, opened with the limit.

“I liffs yo’ jess tree dollahs, Toot,” said the Reverend Mr. Smith, getting out the wallet and shaking out a wad.

Mr. Gus Johnson, who had a four flush and very little prudence, came in.Mr. Whiffles sighed and fled.

Mr. Williams polished the amethyst, thoroughly examining a scratch on one of its facets, adjusted his collar, skinned his cards, stealthily glanced again at the expression of the Reverend Mr. Smith’s eye, and said he would “Jess—jess call.”

Mr. Whiffles supplied the wants of the gentlemen from the pack with the mechanical air of a man who had lost all hope in a hereafter.Mr. Williams wanted one card, the Reverend Mr. Smith said he’d take about three, and Mr. Gus Johnson expressed a desire for a club, if it was not too much trouble.

Mr. Williams caught another tray, and, being secretly pleased, led out by betting a chip.The Reverend Mr. Smith uproariously slammed down a stack of blue chips and raised him seven dollars.

Mr. Gus Johnson had captured the nine of hearts and so retired.

Mr. Williams had four chips and a dollar left.

“I sees dat seven,” he said impressively, “an’ I humps it ten mo’.”

“Whar’s de c’lateral?”queried the Reverend Mr. Smith calmly, but with aggressiveness in his eye.

Mr. Williams sniffed contemptuously, drew off the ring, and deposited it in the pot with such an air as to impress Mr. Whiffles with the idea that the jewel must have been worth at least four million dollars.Then Mr. Williams leaned back in his chair and smiled.

“Whad yer goin’ ter do?”asked the Reverend Mr. Smith, deliberately ignoring Mr. Williams’s action.

Mr. Williams pointed to the ring and smiled.

“Liff yo’ ten dollahs.”

“On whad?”

“Dat ring.”

“Dat ring?”

“Yezzah.”Mr. Williams was still cool.

“Huh!”The Reverend Mr. Smith picked the ring up, examined it scientifically with one eye closed, dropped it several times as if to test its soundness, and then walked across and rasped it several times heavily on the window pane.

“Whad yo’ doin’ dat for?”excitedly asked Mr. Williams.

A double rasp with the ring was the Reverend Mr. Smith’s only reply.

“Gimme dat jule back!”demanded Mr. Williams.

The Reverend Mr. Smith was now vigorously rubbing the setting of the stone on the floor.

“Leggo dat sparkler,” said Mr. Williams again.

The Reverend Mr. Smith carefully polished off the scratches by rubbing the ring awhile on the sole of his foot.Then he resumed his seat and put the precious thing back into the pot.Then he looked calmly at Mr. Williams, and leaned back in his chair as if waiting for something.

“Is yo’ satisfied?”said Mr. Williams, in the tone used by men who have sustained a deep injury.

“Dis is pokah,” said the Reverend Mr. Thankful Smith.

“I rised yo’ ten dollahs,” said Mr. Williams, pointing to the ring.

“Did yer ever saw three balls hangin’ over my do’?”asked the Reverend Mr. Smith.“Doesn’t yo’ know my name hain’t Oppenheimer?”

“Whad yo’ mean?”asked Mr. Williams excitedly.

“Pokah am pokah, and dar’s no ’casion fer triflin’ wif blue glass ’n junk in dis yar club,” said the Reverend Mr. Smith.

“I liffs yo’ ten dollahs,” said Mr. Williams, ignoring the insult.

“Pud up de c’lateral,” said the Reverend Mr. Smith.“Fo’ chips is fohty, ’n a dollah’s a dollah fohty, ’n dat’s a dollah fohty-fo’ cents.”

“Whar’s de fo’ cents?”smiled Mr. Williams, desperately.

The Reverend Mr. Smith pointed to the ring.Mr. Williams rose indignantly, shucked off his coat, hat, vest, suspenders and scarfpin, heaped them on the table, and then sat down and glared at the Reverend Mr. Smith.

Mr. Smith rolled up the coat, put on the hat, threw his own out of the window, gave the ring to Mr. Whiffles, jammed the suspenders into his pocket, and took in the vest, chips and money.

“Dis yar’s buglry!”yelled Mr. Williams.

The Reverend Mr. Smith spread out four eights and rose impressively.

“Toot,” he said, “doan trifle wif Prov’dence.Because a man wars ten cent grease ’n’ gits his july on de Bowery, hit’s no sign dat he kin buck agin cash in a jacker ’n’ git a boodle from fo’ eights.Yo’s now in yo’ shirt sleeves ’n’ low sperrets, bud de speeyunce am wallyble.I’se willin’ ter stan’ a beer an’ sassenger, ’n’ shake ’n’ call it squar’.De club ’ll now ’journ.”

Mr. Blaine used to tell this story:

Once in Dublin, toward the end of the opera, Satan was conducting Faust through a trap-door which represented the gates of Hades.His Majesty got through all right—he was used to going below—but Faust, who was quite stout, got only about half-way in, and no squeezing would get him any farther.Suddenly an Irishman in the gallery exclaimed, devoutly, “Thank God, hell is full.”

While Mark Twain was ill in London a report that he had died was circulated. It spread to America and reached Charles Dudley Warner in Hartford, Connecticut. Mr. Warner immediately cabled to London to find out if it was really so. The cablegram in some way came directly into the humorist’s hands, and he forthwith cabled the following reply: “Reports of my death greatly exaggerated.”

GEORGE T.LANIGAN

THE FOX AND THE CROW

A crow, having secured a Piece of Cheese, flew with its Prize to a lofty Tree, and was preparing to devour the Luscious Morsel, when a crafty Fox, halting at the foot of the Tree, began to cast about how he might obtain it.

“How tasteful is your Dress,” he cried, in well-feigned Ecstacy; “it cannot surely be that your Musical Education has been neglected?Will you not oblige——?”

“I have a horrid Cold,” replied the Crow, “and never sing without my Music; but since you press me—at the same time, I should add that I have read Æsop, and been there before.”

So saying, she deposited the Cheese in a safe Place on the Limb of the Tree, and favored him with a Song.

“Thank you,” exclaimed the Fox, and trotted away, with the Remark that Welsh Rabbits never agreed with him, and were far inferior in Quality to the animate Variety.

Moral—The foregoing fable is supported by a whole Gatling Battery of Morals.We are taught (1) that it Pays to take the Papers; (2) that Invitation is not Always the Sincerest Flattery; (3) that a Stalled Rabbit with Contentment is better than No Bread; and (4) that the Aim of Art is to Conceal Disappointment.

Geo.T.Lanigan.

By permission of Life Publishing Company

HENRY CUYLER BUNNER

BEHOLD THE DEEDS!

(Chant Royal)

Envoy

By permission of Charles Scribner’s Sons

Secretary Chase was not originally a profane man.He learned how to swear after he went into Lincoln’s Cabinet.One day, after he had delivered himself vigorously, Lincoln said to him:

“Mr. Chase, are you an Episcopalian?”

“Why do you ask?”was the somewhat surprised counter-question.

“Oh, just out of curiosity,” replied Lincoln.“Seward is an Episcopalian, and I had noticed that you and he swore in much the same manner.”

Family Physician: “Well, I congratulate you.”

Patient (excitedly): “I will recover?”

Family Physician: “Not exactly, but—well, after consultation, we find that your disease is entirely novel, and if the autopsy should demonstrate that fact we have decided to name it after you.”

AN INSURANCE AGENT’S STORY

“Oh, I guess we have our experiences,” laughed the fire insurance agent.“We are just like others who have to deal with all kinds of people.

“Take the smart Alecs, for instance.They give us a whirl once in awhile, but we generally manage to get as good as a draw with them.It was only last fall that one of them came in and wanted me to insure his coal pile.Of course I caught on at once, but I made out his policy and took his money.In the spring he came around with a broad grin on his face and told me that the coal had been burned—in the furnace, of course.I solemnly informed him that we must decline to settle the loss.He said he would sue.I told him to blaze away, and I would have him arrested as an incendiary.That straightened his face out, and it cost him a tidy little supper for a dozen of us just to insure our silence.

“One shrewd old chap had grown rich out of our company, and when he had built an elegant new store and stocked it with goods he came to us again for insurance.I refused him, but he was persistent, and I finally assented on condition that he hang a gross of hand-grenades in the place.After I had seen them properly distributed, I sent an old chum of his up to get the real lay of the land, for I was still suspicious. This is what the cronies said to each other:

“‘What is them things, Ike?’

“‘Hand-grenades.’

“‘What’s hand-grenades?’

“‘I don’t know what was in ’em at first, but they’re full of kerosene oil now.’

“We canceled the policy.”

A girl from town is staying with some country cousins who live at a farm.On the night of her arrival she finds, to her mortification, that she is ignorant of all sorts of things connected with farm life which to her country cousins are matters of every-day knowledge.She fancies they seem amused at her ignorance.

At breakfast the following morning she sees on the table a dish of fine honey, whereupon she thinks she has found an opportunity of retrieving her humiliating experience of the night before, and of showing her country cousins that she knows something of country life after all.So, looking at the dish of honey, she says carelessly:

“Ah, I see you keep a bee.”

Minister (at baptismal font): “Name, please?”

Mother (baby born abroad): “Philip Ferdinand Chesterfield Randolph y Livingstone.”

Minister (aside to assistant): “Mr. Kneeler, a little more water, please.”

FRANK DEMPSTER SHERMAN

A RHYME FOR PRISCILLA

As the car reached Westville, an old man with a long white beard rose feebly from a corner seat and tottered toward the door.He was, however, stopped by the conductor, who said:

“Your fare, please.”

“I paid my fare.”

“When?I don’t remember it.”

“Why, I paid you when I got on the car.”

“Where did you get on?”

“At Fair Haven.”

“That won’t do!When I left Fair Haven there was only a little boy on the car.”

“Yes,” answered the old man, “I know it.I was that little boy.”

AN EPITAPH

THOMAS BAILEY ALDRICH

A RIVERMOUTH ROMANCE

At five o’clock of the morning of the tenth of July, 1860, the front door of a certain house on Anchor Street, in the ancient seaport town of Rivermouth, might have been observed to open with great caution.This door, as the least imaginative reader may easily conjecture, did not open itself.It was opened by Miss Margaret Callaghan, who immediately closed it softly behind her, paused for a few seconds with an embarrassed air on the stone step, and then, throwing a furtive glance up at the second-story windows, passed hastily down the street toward the river, keeping close to the fences and garden walls on her left.

There was a ghostlike stealthiness to Miss Margaret’s movements, though there was nothing whatever of the ghost about Miss Margaret herself.She was a plump, short person, no longer young, with coal-black hair growing low on the forehead, and a round face that would have been nearly meaningless if the features had not been emphasized—italicized, so to speak—by the smallpox.Moreover, the brilliancy of her toilet would have rendered any ghostly hypothesis untenable.Mrs. Solomon (we refer to the dressiest Mrs. Solomon, whichever one that was) in all her glory was not arrayed like Miss Margaret on that eventful summer morning.She wore a light-green, shot-silk frock, a blazing red shawl, and a yellow crape bonnet profusely decorated with azure, orange and magenta artificial flowers.In her hand she carried a white parasol.The newly risen sun, ricochetting from the bosom of the river and striking point-blank on the top-knot of Miss Margaret’s gorgeousness, made her an imposing spectacle in the quiet street of that Puritan village.But, in spite of the bravery of her apparel, she stole guiltily along by garden walls and fences until she reached a small, dingy frame house near the wharves, in the darkened doorway of which she quenched her burning splendor, if so bold a figure is permissible.

Three-quarters of an hour passed.The sunshine moved slowly up Anchor Street, fingered noiselessly the well-kept brass knockers on either side, and drained the heeltaps of dew which had been left from the revels of the fairies overnight in the cups of the morning-glories.Not a soul was stirring yet in this part of the town, though the Rivermouthians are such early birds that not a worm may be said to escape them.By and by one of the brown Holland shades at one of the upper windows of the Bilkins Mansion—the house from which Miss Margaret had emerged—was drawn up, and old Mr. Bilkins in spiral nightcap looked out on the sunny street. Not a living creature was to be seen save the dissipated family cat—a very Lovelace of a cat that was not allowed a night-key—who was sitting on the curbstone opposite, waiting for the hall door to open. Three-quarters of an hour, we repeat, had passed, when Mrs. Margaret O’Rourke, née Callaghan, issued from the small, dingy house by the river and regained the doorstep of the Bilkins Mansion in the same stealthy fashion in which she had left it.

Not to prolong a mystery that must already oppress the reader, Mr. Bilkins’s cook had, after the manner of her kind, stolen out of the premises before the family were up and got herself married—surreptitiously and artfully married—as if matrimony were an indictable offense.

And something of an offense it was in this instance.In the first place, Margaret Callaghan had lived nearly twenty years with the Bilkins family, and the old people—there were no children now—had rewarded this long service by taking Margaret into their affections.It was a piece of subtle ingratitude for her to marry without admitting the worthy couple to her confidence.

In the next place, Margaret had married a man some eighteen years younger than herself.That was the young man’s lookout, you say.We hold it was Margaret that was to blame.What does a young blade of twenty-two know?Not half so much as he thinks he does.His exhaustless ignorance at that age is a discovery which is left for him to make in his prime.

In one sense Margaret’s husband had come to forty year—she was forty to a day.

Mrs. Margaret O’Rourke, with the baddish cat following closely at her heels, entered the Bilkins mansion, reached her chamber in the attic without being intercepted, and there laid aside her finery.Two or three times, while arranging her more humble attire, she paused to take a look at the marriage certificate, which she had deposited between the leaves of her prayer-book, and on each occasion held that potent document upside down; for Margaret’s literary culture was of the severest order, and excluded the art of reading.

The breakfast was late that morning. As Mrs. O’Rourke set the coffee-urn in front of Mrs. Bilkins and flanked Mr. Bilkins with the broiled mackerel and buttered toast, Mrs. O’Rourke’s conscience smote her. She afterward declared that when she saw the two sitting there so innocent-like, not dreaming of the comether she had put upon them, she secretly and unbeknownst let a few tears fall into the cream pitcher. Whether or not it was this material expression of Margaret’s penitence that spoiled the coffee does not admit of inquiry; but the coffee was bad. In fact, the whole breakfast was a comedy of errors.

It was a blessed relief to Margaret when the meal was ended.She retired in a cold perspiration to the penetralia of the kitchen, and it was remarked by both Mr. and Mrs. Bilkins that those short flights of vocalism—apropos of the personal charms of one Kate Kearney, who lived on the banks of Killarney—which ordinarily issued from the direction of the scullery, were unheard that forenoon.

The town clock was striking eleven, and the antiquated timepiece on the staircase (which never spoke but it dropped pearls and crystals, like the fairy in the story) was lisping the hour, when there came three tremendous knocks at the street door.Mrs. Bilkins, who was dusting the brass-mounted chronometer in the hall, stood transfixed, with arm uplifted.The admirable old lady had for years been carrying on a guerrilla warfare with itinerant venders of furniture polish, and pain-killer, and crockery cement, and the like.The effrontery of the triple knock convinced her the enemy was at her gates—possibly that dissolute creature with twenty-four sheets of note-paper and twenty-four envelopes for fifteen cents.

Mrs. Bilkins swept across the hall and opened the door with a jerk.The suddenness of the movement was apparently not anticipated by the person outside, who, with one arm stretched feebly toward the receding knocker, tilted gently forward and rested both hands on the threshold in an attitude which was probably common enough with our ancestors of the Simian period, but could never have been considered graceful.By an effort that testified to the excellent condition of his muscles, the person instantly righted himself, and stood swaying unsteadily on his toes and heels, and smiling rather vaguely on Mrs. Bilkins.

It was a slightly built but well-knitted young fellow, in the not unpicturesque garb of our marine service. His woolen cap, pitched forward at an acute angle with his nose, showed the back part of a head thatched with short yellow hair, which had broken into innumerable curls of painful tightness. On his ruddy cheeks a sparse, sandy beard was making a timid début. Add to this a weak, good-natured mouth, a pair of devil-may-care blue eyes, and the fact that the man was very drunk, and you have a pre-Raphaelite portrait—we may as well say at once—of Mr. Larry O’Rourke of Mullingar, County Westmeath, and late of the United States sloop-of-war Santee

The man was a total stranger to Mrs. Bilkins; but the instant she caught sight of the double white anchors embroidered on the lapels of his jacket, she unhesitatingly threw back the door, which with great presence of mind she had partly closed.

A drunken sailor standing on the step of the Bilkins mansion was no novelty.The street, as we have stated, led down to the wharves, and sailors were constantly passing.The house abutted directly on the street; the granite doorstep was almost flush with the sidewalk, and the huge old-fashioned brass knocker—seemingly a brazen hand that had been cut off at the wrist, and nailed against the oak as a warning to malefactors—extended itself in a kind of grim appeal to everybody.It seemed to possess strange fascinations for all seafaring folk; and when there was a man-of-war in port the rat-tat-tat of that knocker would frequently startle the quiet neighborhood long after midnight.There appeared to be an occult understanding between it and the blue-jackets.Years ago there was a young Bilkins, one Pendexter Bilkins—a sad losel, we fear—who ran away to try his fortunes before the mast, and fell overboard in a gale off Hatteras.“Lost at sea,” says the chubby marble slab in the Old South Burying Ground, “ætat. 18.” Perhaps that is why no blue-jacket, sober or drunk, was ever repulsed from the door of the Bilkins mansion.

Of course Mrs. Bilkins had her taste in the matter, and preferred them sober.But as this could not always be, she tempered her wind, so to speak, to the shorn lamb.The flushed, prematurely old face that now looked up at her moved the good lady’s pity.

“What do you want?”she asked kindly.

“Me wife.”

“There’s no wife for you here,” said Mrs. Bilkins, somewhat taken aback.“His wife!”she thought; “it’s a mother the poor boy needs.”

“Me wife,” repeated Mr. O’Rourke, “for betther or for worse.”

“You had better go away,” said Mrs. Bilkins, bridling up, “or it will be the worse for you.”

“To have and to howld,” continued Mr. O’Rourke, wandering retrospectively in the mazes of the marriage service, “to have and to howld till death—bad luck to him!—takes one or the ither of us.”

“You’re a blasphemous creature,” said Mrs. Bilkins severely.

“Thim’s the words his riverince spake this mornin’, standin’ foreninst us,” explained Mr. O’Rourke.“I stood here, see, and me jew’l stood there, and the howly chaplain beyont.”

And Mr. O’Rourke with a wavering forefinger drew a diagram of the interesting situation on the doorstep.

“Well,” returned Mrs. Bilkins, “if you’re a married man, all I have to say is, there’s a pair of fools instead of one.You had better be off; the person you want doesn’t live here.”

“Bedad, thin, but she does.”

“Lives here?”

“Sorra a place else.”

“The man’s crazy,” said Mrs. Bilkins to herself.

While she thought him simply drunk, she was not in the least afraid; but the idea that she was conversing with a madman sent a chill over her.She reached back her hand preparatory to shutting the door, when Mr. O’Rourke, with an agility that might have been expected from his previous gymnastics, set one foot on the threshold and frustrated the design.

“I want me wife,” he said sternly.

Unfortunately, Mr. Bilkins had gone uptown, and there was no one in the house except Margaret, whose pluck was not to be depended on.The case was urgent.With the energy of despair Mrs. Bilkins suddenly placed the toe of her boot against Mr. O’Rourke’s invading foot and pushed it away.The effect of this attack was to cause Mr. O’Rourke to describe a complete circle on one leg, and then sit down heavily on the threshold.The lady retreated to the hat-stand, and rested her hand mechanically on the handle of a blue cotton umbrella.Mr. O’Rourke partly turned his head and smiled upon her with conscious superiority.At this juncture a third actor appeared on the scene, evidently a friend of Mr. O’Rourke, for he addressed that gentleman as a “spalpeen,” and told him to go home.

“Divil an inch,” replied the spalpeen; but he got himself off the threshold and resumed his position on the step.

“It’s only Larry, mum,” said the man, touching his forelock politely; “as dacent a lad as ever lived, when he’s not in liquor; an’ I’ve known him to be sober for days togither,” he added, reflectively.“He don’t mane a ha’p’orth o’ harum, but jist now he’s not quite in his right moind.”

“I should think not,” said Mrs. Bilkins, turning from the speaker to Mr. O’Rourke, who had seated himself gravely on the scraper and was weeping.“Hasn’t the man any friends?”

“Too many of ’em, mum, an’ it’s along wid dhrinkin’ toasts wid ’em that Larry got throwed.The punch that spalpeen has dhrunk this day would amaze ye.He give us the slip awhiles ago, bad cess to him, an’ come up here.Didn’t I tell ye, Larry, not to be afther ringin’ at the owle gintleman’s knocker?Ain’t ye got no sinse at all?”

“Misther Donnehugh,” responded Mr. O’Rourke with great dignity, “ye’re dhrunk again.”

Mr. Donnehugh, who had not taken more than thirteen ladles of rum punch, disdained to reply directly.

“He’s a dacent lad enough”—this to Mrs. Bilkins—“but his head is wake.Whin he’s had two sups o’ whisky he belaves he’s dhrunk a bar’lful.A gill o’ wather out of a jimmy-john’d fuddle him, mum.”

“Isn’t there anybody to look after him?”

“No, mum; he’s an orphan.His father and mother live in the owld counthry, an’ a fine, hale owld couple they are.”

“Hasn’t he any family in the town?”

“Sure, mum, he has a family; wasn’t he married this blessed mornin’?”

“He said so.”

“Indade, thin, he was—the pore divil!”

“And the—the person?”inquired Mrs. Bilkins.

“Is it the wife, ye mane?”

“Yes, the wife; where is she?”

“Well, thin, mum,” said Mr. Donnehugh, “it’s yerself can answer that.”

“I?”exclaimed Mrs. Bilkins.“Good heavens!this man’s as crazy as the other!”

“Begorra, if anybody’s crazy, it’s Larry, for it’s Larry has married Margaret.”

“What Margaret?”cried Mrs. Bilkins.

“Margaret Callaghan, sure.”

“Our Margaret? Do you mean to say that OUR Margaret has married that—that good-for-nothing, inebriated wretch?”

“It’s a civil tongue the owld lady has, anyway,” remarked Mr. O’Rourke critically, from the scraper.

Mrs. Bilkin’s voice during the latter part of the colloquy had been pitched in a high key; it rung through the hall and penetrated to the kitchen, where Margaret was wiping the breakfast things.She paused with a half-dried saucer in her hand, and listened.In a moment more she stood, with bloodless face and limp figure, leaning against the banister behind Mrs. Bilkins.

“Is it there ye are, me jew’l!”cried Mr. O’Rourke, discovering her.

Mrs. Bilkins wheeled upon Margaret.

“Margaret Callaghan, is that thing your husband?”

“Ye—yes, mum,” faltered Mrs. O’Rourke, with a woful lack of spirit.

“Then take it away!”cried Mrs. Bilkins.

Margaret, with a slight flush on either cheek, glided past Mrs. Bilkins, and the heavy oak door closed with a bang, as the gates of Paradise must have closed of old upon Adam and Eve.

“Come!”said Margaret, taking Mr. O’Rourke by the hand; and the two wandered forth upon their wedding journey down Anchor Street, with all the world before them where to choose.They chose to halt at the small, shabby tenement-house by the river, through the doorway of which the bridal pair disappeared with a reeling, eccentric gait; for Mr. O’Rourke’s intoxication seemed to have run down his elbow, and communicated itself to Margaret.

O Hymen!who burnest precious gums and scented woods in thy torch at the melting of aristocratic hearts, with what a pitiful penny-dip thou hast lighted up our little back-street romance.—Majorie Daw, and Other Stories.

The story is told of a famous Boston lawyer, that one day, after having a slight discussion with the Judge, he deliberately turned his back upon that personage and started to walk off.

“Are you trying, sir, to show your contempt for the Court?”asked the judge, sternly.

“No, sir,” was the reply; “I am trying to conceal it.”

GELETT BURGESS

THE BOHEMIANS OF BOSTON

In “The Burgess Nonsense Book”

Of the countless good stories attributed to Artemus Ward, the best one, perhaps, is one which tells of the advice which he gave to a Southern railroad conductor soon after the war.The road was in a wretched condition, and the trains were consequently run at a phenomenally low rate of speed.When the conductor was punching his ticket, Artemus remarked:

“Does this railroad company allow passengers to give it advice, if they do so in a respectful manner?”

The conductor replied in gruff tones that he guessed so.

“Well,” Artemus went on, “it occurred to me that it would be well to detach the cowcatcher from the front of the engine and hitch it to the rear of the train, for you see we are not liable to overtake a cow, but what’s to prevent a cow from strolling into this car and biting a passenger?”

MARION COUTHOUY SMITH

THE COMPOSITE GHOST

SOME MESSAGES RECEIVED BY TEACHERS IN BROOKLYN PUBLIC SCHOOLS

The fact that the “Slab City” parents object to clay-modeling in the schools is illustrated in the following note sent to a teacher in one of the Tenth Ward schools:

Miss ——: John kem home yesterday wid his clothes covered wid mud.He said you put him to work mixing clay when he ought to be learning to read an’ write.Me man carries th’ hod, an’ God knows I hev enuf trouble wid his clothes in th’ wash widout scraping John’s coat.If he comes home like this agin I’ll send him back ter yez to wash his clothes.

Mrs. O’R——

Here is one from a Brownsville mother who objects to physical culture:

Miss Brown: You must stop teach my Lizzie fisical torture she needs yet readin’ an’ figors mit sums more as that, if I want her to do jumpin’ I kin make her jump.

Mrs. Canavowsky.

The number of parents who object to the temperance plank in the educational platform is greater than the number of objectors to any other class of study in Williamsburg.Here is a copy of a note sent to a teacher in the Stagg Street school:

Miss ——: My boy tells me that when I trink beer der overcoat vrom my stummack gets to thick.Please be so kind and don’t intervere in my family afairs.

Mr. Chris ——

Here is a sample on the same subject sent to a teacher in the Maujer Street school:

Dear Teacher: You should mine your own bizniss an’ not tell Jake he should not trink bier, so long he lif he trinks the bier an’ he trinks it yen wen bill rains is ded, if you interfer some more I go on the bored of edcation.

W.S.

In this school the teachers are often compelled to listen to long arguments on the excise question, and the parents who call around to argue become greatly excited when told that the children are taught not to taste alcoholic liquors.One little boy told his teacher that his mother had given him orders to get up and leave the classroom during the hour for discussing the alcohol question.The teacher told the boy to ask his mother to call around at the schoolhouse.She wrote this note instead:

Teacher: John says you want to see me.I have a bier saloon and nine children.Bizness is good in morning an’ aft’noon.How can I come?

The Pickleville parents as a rule never omit the “obliging” end of a note, as will be seen in the following, sent to a teacher of the Wall Street school:

Dear Teacher: Pleas excus Fritz for staying home he had der meesells to oblige his father.

J.B.

And here is another of the obliging kind:

Teacher: Please excuse Henny for not comeing in school as he died from the car run-over on Tuesday.By doing so you will greatly oblige his loving mother.

Here is one sent to the Brownsville school:

Dear Miss Baker: Please excuse Rachael for being away those two days her grandmother died to oblige her mother.

Mrs. Renski.

The child mentioned in the following note was neither German nor Irish.But he is back in school after a battle with the doctors:

Miss ——: Frank could not come these three weeks because he had the amonia and information of the vowels.

Mrs. Smith.

The notes sent are sometimes written on scented paper, and as a rule these are misspelled.Here is a scented-paper sample:

Teacher: You must excuse my girl for not coming to school, she was sick and lade in a common dose state for tree days.

Mrs. W.

In this same school a teacher received the following:

Miss ——: Please let Willie home at 2 o’clock.I take him out for a little pleasure to see his grandfather’s grave.

Mrs. R.

Still another mother wrote the following:

Miss ——: Please be so kind an’ knock hell out of Sol when he gives too much lip to oblige his mother.

THE TROUT’S APPEAL

BILL NYE

A FATAL THIRST

From the London Lancet we learn that “many years ago a case was recorded by Doctor Otto, of Copenhagen, in which 495 needles passed through the skin of a hysterical girl, who had probably swallowed them during a hysterical paroxysm, but these all emerged from the regions below the diaphragm, and were collected in groups, which gave rise to inflammatory swellings of some size. One of these contained 100 needles. Quite recently Doctor Bigger described before the Society of Surgery of Dublin a case in which more than 300 needles were removed from the body of a woman. It is very remarkable in how few cases the needles were the cause of death, and how slight an interference with function their presence and movement cause.”

It would seem, from the cases on record, that needles in the system rather assist in the digestion and promote longevity.

For instance, we will suppose that the hysterical girl above alluded to, with 495 needles in her stomach, should absorb the midsummer cucumber.Think how interesting those needles would make it for the great colic promoter!

We can imagine the cheerful smile of the cucumber as it enters the stomach, and, bowing cheerfully to the follicles standing around, hangs its hat upon the walls of the stomach, stands its umbrella in a corner, and proceeds to get in its work.

All at once the cucumber looks surprised and grieved about something.It stops in its heaven-born colic generation, and pulls a rusty needle out of its person.Maddened by the pain, it once more attacks the digestive apparatus, and once more accumulates a choice job lot of needles.

Again and again it enters into the unequal contest, each time losing ground and gaining ground, till the poor cucumber, with assorted hardware sticking out in all directions, like the hair on a cat’s tail, at last curls up like a caterpillar and yields up the victory.

Still, this needle business will be expensive to husbands, if wives once acquire the habit and allow it to obtain the mastery over them.

If a wife once permits this demon appetite for cambric needles to get control of the house, it will soon secure a majority in the senate, and then there will be trouble.

The woman who once begins to tamper with cambric needles is not safe.She may think that she has power to control her appetite, but it is only a step to the maddening thirst for the darning-needle, and perhaps to the button-hook and carpet-stretcher.

It is safer and better to crush the first desire for needles than to undertake when it is too late reformation from the abject slavery to this hellish thirst.

We once knew a sweet young creature, with dewy eye and breath like timothy hay.Her merry laugh rippled out upon the summer air like the joyful music of baldheaded bobolinks.

Everybody loved her, and she loved everybody too.But in a thoughtless moment she swallowed a cambric needle.This did not satisfy her.The cruel thraldom had begun.Whenever she felt depressed and gloomy, there was nothing that would kill her ennui and melancholy but the fatal needle-cushion.

From this she rapidly became more reckless, till there was hardly an hour that she was not under the influence of needles.

If she couldn’t get needles to assuage her mad thirst, she would take hairpins or door-keys.She gradually pined away to a mere skeleton.She could no longer sit on one foot and be happy.

Life for her was filled with opaque gloom and sadness.At last she took an overdose of sheep-shears and monkey-wrenches one day, and on the following morning her soul had lit out for the land of eternal summer.

We should learn from this to shun the maddening needle-cushion as we would a viper, and never tell a lie.

GEORGE W.PECK

PECK’S BAD BOY

“Say, are you a Mason, or a Nodfellow, or anything?”asked the bad boy of the grocery man, as he went to the cinnamon bag on the shelf and took out a long stick of cinnamon bark to chew.

“Why, yes, of course I am; but what set you to thinking of that?”asked the grocery man, as he went to the desk and charged the boy’s father with a half-pound of cinnamon.

“Well, do the goats bunt when you nishiate a fresh candidate?”

“No, of course not.The goats are cheap ones, that have no life, and we muzzle them, and put pillows over their heads so they can’t hurt anybody,” said the grocery man, as he winked at a brother Oddfellow who was seated on a sugar barrel, looking mysterious.“But why do you ask?”

“Oh, nothin’, only I wish me and my chum had muzzled our goat with a pillow.Pa would have enjoyed his becoming a member of our lodge better.You see, Pa had been telling us how much good the Masons and Oddfellers did, and said we ought to try and grow up good so we could jine the lodges when we got big; and I asked Pa if it would do any hurt for us to have a play lodge in my room, and purtend to nishiate, and Pa said it wouldn’t do any hurt.He said it would improve our minds and learn us to be men. So my chum and me borried a goat that lives in a livery stable. Say, did you know they keep a goat in a livery stable so the horses won’t get sick? They get used to the smell of the goat, and after that nothing can make them sick but a glue factory. You see, my chum and me had to carry the goat up to my room when Ma and Pa was out riding, and he blatted so we had to tie a handkerchief around his nose, and his feet made such a noise on the floor that we put some baby’s socks on his hoofs.