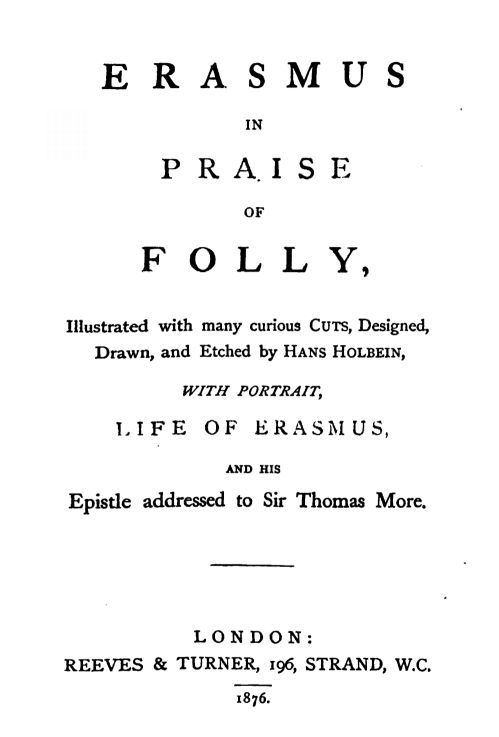

In Praise of Folly / Illustrated with Many Curious Cuts

Play Sample

In the same predicament of fools are to be ranked such, as while they are yet living, and in good health, take so great a care how they shall be buried when they die, that they solemnly appoint how many torches, how many escutcheons, how many gloves to be given, and how many mourners they will have at their funeral; as if they thought they themselves in their coffins could be sensible of what respect was paid to their corpse; or as if they doubted they should rest a whit the less quiet in the grave if they were with less state and pomp interred.

Now though I am in so great haste, as I would not willingly be stopped or detained, yet I cannot pass by without bestowing some remarks upon another sort of fools; who, though their first descent was perhaps no better than from a tapster or tinker, yet highly value themselves upon their birth and parentage. One fetches his pedigree from AEneas, another from Brute, a third from king Arthur: they hang up their ancestors' worm-eaten pictures as records of antiquity, and keep a long list of their predecessors, with an account of all their offices and tides, while they themselves are but transcripts of their forefathers' dumb statues, and degenerate even into those very beasts which they carry in their coat of arms as ensigns of their nobility: and yet by a strong presumption of their birth and quality, they live not only the most pleasant and unconcerned themselves, but there are not wanting others too who cry up these brutes almost equal to the gods. But why should I dwell upon one or two instances of Folly, when there are so many of like nature. Conceitedness and self-love making many by strength of Fancy believe themselves happy, when otherwise they are really wretched and despicable. Thus the most ape-faced, ugliest fellow in the whole town, shall think himself a mirror of beauty: another shall be so proud of his parts, that if he can but mark out a triangle with a pair of compasses, he thinks he has mastered all the difficulties of geometry, and could outdo Euclid himself. A third shall admire himself for a ravishing musician, though he have no more skill in the handling of any instrument than a pig playing on the organs: and another that rattles in the throat as hoarse as a cock crows, shall be proud of his voice, and think he sings like a nightingale.

There is another very pleasant sort of madness, whereby persons assume to themselves whatever of accomplishment they discern in others. Thus the happy rich churl in Seneca, who had so short a memory, as he could not tell the least story without a servant standing by to prompt him, and was at the same time so weak that he could scarce go upright, yet he thought he might adventure to accept a challenge to a duel, because he kept at home some lusty, sturdy fellows, whose strength he relied upon instead of his own.

It is almost needless to insist upon the several professors of arts and sciences, who are all so egregiously conceited, that they would sooner give up their title to an estate in lands, than part with the reversion of their wits: among these, more especially stage-players, musicians, orators, and poets, each of which, the more of duncery they have, and the more of pride, the greater is their ambition: and how notoriously soever dull they be, they meet with their admirers; nay, the more silly they are the higher they are extolled; Folly (as we have before intimated) never failing of respect and esteem. If therefore every one, the more ignorant he is, the greater satisfaction he is to himself, and the more commended by others, to what purpose is it to sweat and toil in the pursuit of true learning, which shall cost so many gripes and pangs of the brain to acquire, and when obtained, shall only make the laborious student more uneasy to himself, and less acceptable to others?

As nature in her dispensation of conceited-ness has dealt with private persons, so has she given a particular smatch of self-love to each country and nation. Upon this account it is that the English challenge the prerogative of having the most handsome women, of the being most accomplished in the skill of music, and of keeping the best tables: the Scotch brag of their gentility, and pretend the genius of their native soil inclines them to be good disputants: the French think themselves remarkable for complaisance and good breeding: the Sorbonists of Paris pretend before any others to have made the greatest proficiency in polemic divinity: the Italians value themselves for learning and eloquence; and, like the Grecians of old, account all the world barbarians in respect of themselves; to which piece of vanity the inhabitants of Rome are more especially addicted, pretending themselves to be owners of all those heroic virtues, which their city so many ages since was deservedly famous for. The Venetians stand upon their birth and pedigree. The Grecians pride themselves in having been the first inventors of most arts, and in their country being famed for the product of so many eminent philosophers. The Turks, and all the other refuse of Mahometism, pretend they profess the only true religion, and laugh at all Christians for superstitious, narrow-souled fools. The Jews to this day expect their Messias as devoudy as they believe in their first prophet Moses. The Spaniards challenge the repute of being accounted good soldiers. And the Germans are noted for their tall, proper stature, and for their skill in magick. But not to mention any more, I suppose you are already convinced how great an improvement and addition to the happiness of human life is occasioned by self-love: next step to which is flattery; for as self-love is nothing but the coaxing up of ourselves, so the same currying and humouring of others is termed flattery.

Flattery, it is true, is now looked upon as a scandalous name, but it is by such only as mind words more than things. They are prejudiced against it upon this account, because they suppose it justles out all truth and sincerity? whereas indeed its property is quite contrary, as appears from the examples of several brute creatures. What is more fawning than a spaniel?

And yet what is more faithful to his master? What is more fond and loving than a tame squirrel? And yet what is more sporting and inoffensive? This little frisking creature is kept up in a cage to play withal, while lions, tigers, leopards, and such other savage emblems of rapine and cruelty are shewn only for state and rarity, and otherwise yield no pleasure to their respective keepers.

There is indeed a pernicious destructive sort of flattery wherewith rookers and sharks work their several ends upon such as they can make a prey of, by decoying them into traps and snares beyond recovery: but that which is the effect of folly is of a much different nature; it proceeds from a softness of spirit, and a flexibleness of good humour, and comes far nearer to virtue than that other extreme of friendship, namely, a stiff, sour, dogged moroseness: it refreshes our minds when tired, enlivens them when melancholy, reinforces them when languishing, invigorates them when heavy, recovers them when sick, and pacifies them when rebellious: it puts us in a method how to procure friends, and how to keep them; it entices children to swallow the bitter rudiments of learning; it gives a new ferment to the almost stagnated souls of old men; it both reproves and instructs principles without offence under the mask of commendation: in short, it makes every man fond and indulgent of himself, which is indeed no small part of each man's happiness, and at the same time renders him obliging and complaisant in all company, where it is pleasant to see how the asses rub and scratch one another.

This again is a great accomplishment to an orator, a greater to a physician, and the only one to a poet: in fine, it is the best sweetener to all afflictions, and gives a true relish to the otherwise insipid enjoyments of our whole life. Ay, but (say you) to flatter is to deceive; and to deceive is very harsh and hurtful: no, rather just contrary; nothing is more welcome and bewitching than the being deceived. They are much to be blamed for an undistinguishing head, that make a judgment of things according to what they are in themselves, when their whole nature consists barely in the opinions that are had of them. For all sublunary matters are enveloped in such a cloud of obscurity, that the short-sightedness of human understanding, cannot pry through and arrive to any comprehensive knowledge of them: hence the sect of academic philosophers have modestly resolved, that all things being no more than probable, nothing can be known as certain; or if there could, yet would it but interrupt and abate from the pleasure of a more happy ignorance. Finally, our souls are so fashioned and moulded, that they are sooner captivated by appearances, than by real truths; of which, if any one would demand an example, he may find a very familiar one in churches, where, if what is delivered from the pulpit be a grave, solid, rational discourse, all the congregation grow weary, and fall asleep, till their patience be released; whereas if the preacher (pardon the impropriety of the word, the prater I would have said) be zealous, in his thumps of the cushion, antic gestures, and spend his glass in the telling of pleasant stories, his beloved shall then stand up, tuck their hair behind their ears, and be very devoutly attentive. So among the saints, those are most resorted to who are most romantic and fabulous: as for instance, a poetic St. George, a St. Christopher, or a St. Barbara, shall be oftener prayed to than St. Peter, St. Paul, nay, perhaps than Christ himself; but this, it is possible, may more properly be referred to another place.

In the mean while observe what a cheap purchase of happiness is made by the strength of fancy. For whereas many things even of inconsiderable value, would cost a great deal of pains and perhaps pelf, to procure; opinion spares charges, and yet gives us them in as ample a manner by conceit, as if we possessed them in reality. Thus he who feeds on such a stinking dish of fish, as another must hold his nose at a yard's distance from, yet if he feed heartily, and relish them palateably, they are to him as good as if they were fresh caught: whereas on the other hand, if any one be invited to never so dainty a joul of sturgeon, if it go against his stomach to eat any, he may sit a hungry, and bite his nails with greater appetite than his victuals. If a woman be never so ugly and nauseous, yet if her husband can but think her handsome, it is all one to him as if she really were so: if any man have never so ordinary and smutty a draught, yet if he admires the excellency of it, and can suppose it to have been drawn by some old Apelles, or modern Vandyke, he is as proud of it as if it had really been done by one of their hands. I knew a friend of mine that presented his bride with several false and counterfeit stones, making her believe that they were right jewels, and cost him so many hundred thousand crowns; under his mistake the poor woman was as choice of pebbles, and painted glass, as if they had been so many natural rubies and diamonds, while the subtle husband saved a great deal in his pocket, and yet made his wife as well pleased as if he had been at ten hundred times the cost What difference is there between them that in the darkest dungeon, can with a platonic brain survey the whole world in idea, and him that stands in the open air, and takes a less deluding prospect of the universe? If the beggar in Lucian, that dreamt he was a prince, had never waked, his imaginary kingdom had been as great as a real one. Between him therefore that truly is happy, and him that thinks himself so, there is no perceivable distinction; or if any, the fool has the better of it: first, because his happiness costs him less, standing him only in the price of a single thought; and then, secondly, because he has more fellow-companions and partakers of his good fortune: for no enjoyment is comfortable where the benefit is not imparted to others; nor is any one station of life desirable, where we can have no converse with persons of the same condition with ourselves: and yet this is the hard fate of wise men, who are grown so scarce, that like Phoenixes, they appear but one in an age. The Grecians, it is true, reckoned up seven within the narrow precincts of their own country; yet I believe, were they to cast up their accounts anew, they would not find a half, nay, not a third part, of one in far larger extent.

Farther, when among the several good properties of Bacchus this is looked upon as the chief, namely, that he drowns the cares and anxieties of the mind, though it be indeed but for a short while; for after a small nap, when our brains are a little settled, they all return to their former corrodings: how much greater is the more durable advantage which I bring? while by one uninterrupted fit of being drunk in conceit, I perpetually cajole the mind with riots, revels, and all the excess and energy of joy.

Add to this, that I am so communicative and bountiful, as to let no one particular person pass without some token of my favour; whereas other deities bestow their gifts sparingly to their elect only. Bacchus has not thought fit that every soil should bear the same juice-yielding grape: Venus has not given to all a like portion of beauty: Mercury endows but few with the knack of an accomplished eloquence: Hercules gives not to all the same measure of wealth and riches: Jupiter has ordained but a few to be born to a kingdom: Mars in battle gives a complete victory but to one party; nay, he often makes them both losers: Apollo does not answer the expectation of all that consult his oracles: Jove oft thunders: Phoebus sometimes shoots the plague, or some other infection, at the point of his darts: and Neptune swallows down more than he bears up: not to mention their Ve-Jupiters, their Plutos, their Ate goddess of loss, their evil geniuses, and such other monsters of divinity, as had more of the hangman than the god in them, and were worshipped only to deprecate that hurt which used to be inflicted by them: I say, not to mention these, I am that high and mighty goddess, whose liberality is of as large an extent as her omnipotence: I give to all that ask: I never appear sullen, nor out of humour, nor ever demand any atonement or satisfaction for the omission of any ceremonious punctilio in my worship: I do not storm or rage, if mortals, in their addresses to the other gods pass me by unregarded, without the acknowledgment of any respect or application: whereas all the other gods are so scrupulous and exact, that it often proves less dangerous manfully to despise them, than sneakingly to attempt the difficulty of pleasing them. Thus some men are of that captious, froward humour, that a man had better be wholly strangers to them, than never so intimate friends.

Well, but there are none (say you) build any altars, or dedicate any temple to Folly. I admire (as I have before intimated) that the world should be so wretchedly ungrateful. But I am so good natured as to pass by and pardon this seeming affront, though indeed the charge thereof, as unnecessary, may well be saved; for to what purpose should I demand the sacrifice of frankincense, cakes, goats, and swine, since all persons everywhere pay me that more acceptable service, which all divines agree to be more effectual and meritorious, namely, an imitation of my communicable attributes? I do not therefore any way envy Diana for having her altars bedewed with human blood: I think myself then most religiously adored, when my respective devotees (as is their usual custom) conform themselves to my practice, transcribe my pattern, and so live the copy of me their original. And truly this pious devotion is not so much in use among christians as is much to be wished it were: for how many zealous votaries are there that pay so profound respect to the Virgin Mary, as to place lighted tapers even at noon day upon her altars? And yet how few of them copy after her untouched chastity, her modesty, and her other commendable virtues, in the imitation whereof consists the truest esteem of divine worship? Farther, why should I desire a temple, since the whole world is but one ample continued choir, entirely dedicated to my use and service? Nor do I want worshippers at any place where the earth wants not inhabitants. And as to the manner of my worship, I am not yet so irrecoverably foolish, as to be prayed to by proxy, and to have my honour intermediately bestowed upon senseless images and pictures, which quite subvert the true end of religion; while the unwary supplicants seldom distinguish betwixt the things themselves and the objects they represent The same respect in the meanwhile is paid to me in a more legitimate manner; for to me there are as many statues erected as there are moving fabrics of mortality; every person, even against his own will, carrying the image of me, i.e. the signal of Folly instamped on his countenance. I have not therefore the least tempting inducement to envy the more seeming state and splendour of the other gods, who are worshipped at set times and places; as Phoebus at Rhodes, Venus in her Cyprian isle, Juno in the city Argos, Minerva at Athens, Jupiter on the hill Olympus, Neptune at Tarentum, and Priapus in the town of Lampsacum; while my worship extending as far as my influence, the whole world is my one altar, whereon the most valuable incense and sacrifice is perpetually offered up.

But lest I should seem to speak this with more of confidence than truth, let us take a nearer view of the mode of men's lives, whereby it will be rendered more apparently evident what largesses I everywhere bestow, and how much I am respected and esteemed of persons, from the highest to the basest quality. For the proof whereof, it being too tedious to insist upon each particular, I shall only mention such in general as are most worthy the remark, from which by analogy we may easily judge of the remainder. And indeed to what purpose would it be singly to recount the commonalty and rabble of mankind, who beyond all question are entirely on my side? and for a token of their vassalage do wear my livery in so many older shapes, and more newly invented modes of Folly, that the lungs of a thousand Democrituses would never hold out to such a laughter as this subject would excite; and to these thousand must be superadded one more, to laugh at them as much as they do at the other.

It is indeed almost incredible to relate what mirth, what sport, what diversion, the grovelling inhabitants here on earth give to the above-seated gods in heaven: for these exalted deities spend their fasting sober hours in listening to those petitions that are offered up, and in succouring such as they are appealed to by for redress; but when they are a little entered at a glass of nectar, they then throw off all serious concerns, and go and place themselves on the ascent of some promontory in heaven, and from thence survey the little mole-hill of earth. And trust me, there cannot be a more delightsome prospect, than to view such a theatre so stuffed and crammed with swarms of fools. One falls desperately in love, and the more he is slighted the more does his spaniel-like passion increase; another is wedded to wealth rather than to a wife; a third pimps for his own spouse, and is content to be a cuckold so he may wear his horns gilt; a fourth is haunted with a jealousy of his visiting neighbours; another sobs and roars, and plays the child, for the death of a friend or relation; and lest his own tears should not rise high enough to express the torrent of his grief, he hires other mourners to accompany the corpse to the grave, and sing its requiem in sighs and lamentations; another hypocritically weeps at the funeral of one whose death at heart he rejoices for; here a gluttonous cormorant, whatever he can scrape up, thrusts all into his guts to pacify the cryings of a hungry stomach; there a lazy wretch sits yawning and stretching, and thinks nothing so desirable as sleep and idleness; some are extremely industrious in other men's business, and sottishly neglectful of their own; some think themselves rich because their credit is great, though they can never pay, till they break, and compound for their debts; one is so covetous that he lives poor to die rich; one for a little uncertain gain will venture to cross the roughest seas, and expose his life for the purchase of a livelihood; another will depend on the plunders of war, rather than on the honest gains of peace; some will close with and humour such warm old blades as have a good estate, and no children of their own to bestow it upon; others practice the same art of wheedling upon good old women, that have hoarded and coffered up more bags than they know how to dispose of; both of these sly flatteries make fine sport for the gods, when they are beat at their own weapons, and (as oft happens) are gulled by those very persons they intended to make a prey of.

There is another sort of base scoundrels in gentility, such scraping merchants, who although, for the better vent of their commodities they lie, swear, cheat, and practice all the intrigues of dishonesty, yet think themselves no way inferior to persons of the highest quality, only because they have raked together a plentiful estate; and there are not wanting such insinuating hangers on, as shall caress and compliment them with the greatest respect, in hopes to go snacks in some of their dishonest gains; there are others so infected with the philosophical paradox of banishing property, and having all things in common, that they make no conscience of fastening on, and purloining whatever they can get, and converting it to their own use and possession; there are some who are rich only in wishes, and yet while they barely dream of vast mountains of wealth, they are as happy as if their imaginary fancies commenced real truths; some put on the best side outermost, and starve themselves at home to appear gay and splendid abroad; one with an open-handed freedom spends all he lays his fingers on; another with a logic-fisted gripingness catches at and grasps all he can come within the reach of; one apes it about in the streets to court popularity; another consults his ease, and sticks to the confinement of a chimney-corner; many others are tugging hard at law for a trifle, and drive on an endless suit, only to enrich a deferring judge, or a knavish advocate; one is for new-modelling a settled government; another is for some notable heroical attempt; and a third by all means must travel a pilgrim to Rome, Jerusalem, or some shrine of a saint elsewhere, though he have no other business than the paying of a formal impertinent visit, leaving his wife and children to fast, while he himself forsooth is gone to pray.

In short, if (as Lucian fancies Menippus to have done heretofore,) any man could now again look down from the orb of the moon, he would see thick swarms as it were of flies and gnats, that were quarrelling with each other, justling, fighting, fluttering, skipping, playing, just new produced, soon after decaying, and then immediately vanishing; and it can scarce be thought how many tumults and tragedies so inconsiderate a creature as man does give occasion to, and that in so short a space as the small span of life; subject to so many casualties, that the sword, pestilence, and other epidemic accidents, shall many times sweep away whole thousands at a brush.

But hold; I should but expose myself too far, and incur the guilt of being roundly laughed at, if I proceed to enumerate the several kinds of the folly of the vulgar. I shall confine therefore my following discourse only to such as challenge the repute of wisdom, and seemingly pass for men of the soundest intellectuals. Among whom the Grammarians present themselves in the front, a sort of men who would be the most miserable, the most slavish, and the most hateful of all persons, if I did not in some way alleviate the pressures and miseries of their profession by blessing them with a bewitching sort of madness: for they are not only liable to those five curses, which they so oft recite from the first five verses of Homer, but to five hundred more of a worse nature; as always damned to thirst and hunger, to be choked with dust in their unswept schools (schools, shall I term them, or rather elaboratories, nay, bridewells, and houses of correction?) , to wear out themselves in fret and drudgery; to be deafened with the noise of gaping boys; and in short, to be stifled with heat and stench; and yet they cheerfully dispense with all these inconveniences, and, by the help of a fond conceit, think themselves as happy as any men living: taking a great pride and delight in frowning and looking big upon the trembling urchins, in boxing, slashing, striking with the ferula, and in the exercise of all their other methods of tyranny; while thus lording it over a parcel of young, weak chits, they imitate the Cuman ass, and think themselves as stately as a lion, that domineers over all the inferior herd. Elevated with this conceit, they can hold filth and nastiness to be an ornament; can reconcile their nose to the most intolerable smells; and finally, think their wretched slavery the most arbitrary kingdom, which they would not exchange for the jurisdiction of the most sovereign potentate: and they are yet more happy by a strong persuasion of their own parts and abilities; for thus when their employment is only to rehearse silly stories, and poetical fictions, they will yet think themselves wiser than the best experienced philosopher; nay, they have an art of making ordinary people, such as their school boys' fond parents, to think them as considerable as their own pride has made them. Add hereunto this other sort of ravishing pleasure: when any of them has found out who was the mother of Anchises, or has lighted upon some old unusual word, such as bubsequa, bovinator, manticulator, or other like obsolete cramp terms; or can, after a great deal of poring, spell out the inscription of some battered monument; Lord! what joy, what triumph, what congratulating their success, as if they had conquered Africa, or taken Babylon the Great! When they recite some of their frothy, bombast verses, if any happen to admire them, they are presendy flushed with the least hint of commendation, and devoudy thank Pythagoras for his grateful hypothesis, whereby they are now become actuated with a descent of Virgil's poetic soul. Nor is any divertisement more pleasant, than when they meet to flatter and curry one another; yet they are so critical, that if any one hap to be guilty of the least slip, or seeming blunder, another shall presendy correct him for it, and then to it they go in a tongue-combat, with all the fervour, spleen, and eagerness imaginable. May Priscian himself be my enemy if what I am now going to say be not exactly true. I knew an old Sophister that was a Grecian, a latinist, a mathematician, a philosopher, a musician, and all to the utmost perfection, who, after threescore years' experience in the world, had spent the last twenty of them only in drudging to conquer the criticisms of grammar, and made it the chief part of his prayers, that his life might be so long spared till he had learned how righdy to distinguish betwixt the eight parts of speech, which no grammarian, whether Greek or Latin, had yet accurately done. If any chance to have placed that as a conjunction which ought to have been used as an adverb, it is a sufficient alarm to raise a war for doing justice to the injured word. And since there have been as many several grammars, as particular grammarians (nay, more, for Aldus alone wrote five distinct grammars for his own share), the schoolmaster must be obliged to consult them all, sparing for no time nor trouble, though never so great, lest he should be otherwise posed in an unobserved criticism, and so by an irreparable disgrace lose the reward of all his toil. It is indifferent to me whether you call this folly or madness, since you must needs confess that it is by my influence these school-tyrants, though in never so despicable a condition, are so happy in their own thoughts, that they would not change fortunes with the most illustrious Sophi of Persia.

The Poets, however somewhat less beholden to me, own a professed dependence on me, being a sort of lawless blades, that by prescription claim a license to a proverb, while the whole intent of their profession is only to smooth up and tickle the ears of fools, that by mere toys and fabulous shams, with which (however ridiculous) they are so bolstered up in an airy imagination, as to promise themselves an everlasting name, and promise, by their balderdash, at the same time to celebrate the never-dying memory of others. To these rapturous wits self-love and flattery are never-failing attendants; nor do any prove more zealous or constant devotees to folly.

The Rhetoricians likewise, though they are ambitious of being ranked among the Philosophers, yet are apparently of my faction, as appears among other arguments, by this more especially; in that among their several topics of completing the art of oratory, they all particularly insist upon the knack of jesting, which is one species of folly; as is evident from the books of oratory wrote to Herennius, put among Cicero's work, but done by some other unknown author; and in Quintilian, that great master of eloquence, there is one large chapter spent in prescribing the methods of raising laughter: in short, they may well attribute a great efficacy to folly, since on any argument they can many times by a slight laugh over what they could never seriously confute.

Of the same gang are those scribbling fops, who think to eternize their memory by setting up for authors: among which, though they are all some way indebted to me, yet are those more especially so, who spoil paper in blotting it with mere trifles and impertinences. For as to those graver drudgers to the press, that write learnedly, beyond the reach of an ordinary reader, who durst submit their labours to the review of the most severe critic, these are not so liable to be envied for their honour, as to be pitied for their sweat and slavery. They make additions, alterations, blot out, write anew, amend, interline, turn it upside down, and yet can never please their fickle judgment, but that they shall dislike the next hour what they penned the former; and all this to purchase the airy commendations of a few understanding readers, which at most is but a poor reward for all their fastings, watchings, confinements, and brain-breaking tortures of invention. Add to this the impairing of their health, the weakening of their constitution, their contracting sore eyes, or perhaps turning stark blind; their poverty, their envy, their debarment from all pleasures, their hastening on old age, their untimely death, and what other inconveniences of a like or worse nature can be thought upon: and yet the recompense for all this severe penance is at best no more than a mouthful or two of frothy praise. These, as they are more laborious, so are they less happy than those other hackney scribblers which I first mentioned, who never stand much to consider, but write what comes next at a venture, knowing that the more silly their composures are, the more they will be bought up by the greater number of readers, who are fools and blockheads: and if they hap to be condemned by some few judicious persons, it is an easy matter by clamour to drown their censure, and to silence them by urging the more numerous commendations of others. They are yet the wisest who transcribe whole discourses from others, and then reprint them as their own. By doing so they make a cheap and easy seizure to themselves of that reputation which cost the first author so much time and trouble to procure. If they are at any time pricked a little in conscience for fear of discovery, they feed themselves however with this hope, that if they be at last found plagiaries, yet at least for some time they have the credit of passing for the genuine authors. It is pleasant to see how all these several writers are puffed up with the least blast of applause, especially if they come to the honour of being pointed at as they walk along the streets, when their several pieces are laid open upon every bookseller's stall, when their names are embossed in a different character upon the tide-page, sometime only with the two first letters, and sometime with fictitious cramp terms, which few shall understand the meaning of; and of those that do, all shall not agree in their verdict of the performance; some censuring, others approving it, men's judgments being as different as their palates, that being toothsome to one which is unsavoury and nauseous to another: though it is a sneaking piece of cowardice for authors to put feigned names to their works, as if, like bastards of their brain, they were afraid to own them. Thus one styles himself Telemachus, another Stelenus, a third Polycrates, another Thrasyma-chus, and so on. By the same liberty we may ransack the whole alphabet, and jumble together any letters that come next to hand. It is farther very pleasant when these coxcombs employ their pens in writing congratulatory episdes, poems, and panegyricks, upon each other, wherein one shall be complimented with the title of Alcaeus, another shall be charactered for the incomparable Callimachus; this shall be commended for a completer orator than Tully himself; a fourth shall be told by his fellow-fool that the divine Plato comes short of him for a philosophic soul. Sometime again they take up the cudgels, and challenge out an antagonist, and so get a name by a combat at dispute and controversy, while the unwary readers draw sides according to their different judgments: the longer the quarrel holds the more irreconcilable it grows; and when both parties are weary, they each pretend themselves the conquerors, and both lay claim to the credit of coming off with victory. These fooleries make sport for wise men, as being highly absurd, ridiculous and extravagant True, but yet these paper-combatants, by my assistance, are so flushed with a conceit of their own greatness, that they prefer the solving of a syllogism before the sacking of Carthage; and upon the defeat of a poor objection carry themselves more triumphant than the most victorious Scipio.

Nay, even the learned and more judicious, that have wit enough to laugh at the other's folly, are very much beholden to my goodness; which (except ingratitude have drowned their ingenuity), they must be ready upon all occasions to confess. Among these I suppose the lawyers will shuffle in for precedence, and they of all men have the greatest conceit of their own abilities. They will argue as confidently as if they spoke gospel instead of law; they will cite you six hundred several precedents, though not one of them come near to the case in hand; they will muster up the authority of judgments, deeds, glosses, and reports, and tumble over so many musty records, that they make their employ, though in itself easy, the greatest slavery imaginable; always accounting that the best plea which they have took most pains for.

To these, as bearing great resemblance to them, may be added logicians and sophisters, fellows that talk as much by rote as a parrot; who shall run down a whole gossiping of old women, nay, silence the very noise of a belfry, with louder clappers than those of the steeple; and if their unappeasable clamorousness were their only fault it would admit of some excuse; but they are at the same time so fierce and quarrelsome, that they will wrangle bloodily for the least trifle, and be so over intent and eager, that they many times lose their game in the chase and fright away that truth they are hunting for. Yet self-conceit makes these nimble disputants such doughty champions, that armed with three or four close-linked syllogisms, they shall enter the lists with the greatest masters of reason, and not question the foiling of them in an irresistible way, nay, their obstinacy makes them so confident of their being in the right, that all the arguments in the world shall never convince them to the contrary.

Next to these come the philosophers in their long beards and short cloaks, who esteem themselves the only favourites of wisdom, and look upon the rest of mankind as the dirt and rubbish of the creation: yet these men's happiness is only a frantic craziness of brain; they build castles in the air, and infinite worlds in a vacuum. They will give you to a hair's breadth the dimensions of the sun, moon, and stars, as easily as they would do that of a flaggon or pipkin: they will give a punctual account of the rise of thunder, of the origin of winds, of the nature of eclipses, and of all the other abstrusest difficulties in physics, without the least demur or hesitation, as if they had been admitted into the cabinet council of nature, or had been eye-witnesses to all the accurate methods of creation; though alas nature does but laugh at all their puny conjectures; for they never yet made one considerable discovery, as appears in that they are unanimously agreed in no one point of the smallest moment; nothing so plain or evident but what by some or other is opposed and contradicted. But though they are ignorant of the artificial contexture of the least insect, they vaunt however, and brag that they know all things, when indeed they are unable to construe the mechanism of their own body: nay, when they are so purblind as not to be able to see a stone's cast before them, yet they shall be as sharp-sighted as possible in spying-out ideas, universals separate forms, first matters, quiddities, formalities, and a hundred such like niceties, so diminutively small, that were not their eyes extremely magnifying, all the art of optics could never make them discernible. But they then most despise the low grovelling vulgar when they bring out their parallels, triangles, circles, and other mathematical figures, drawn up in battalia, like so many spells and charms of conjuration in muster, with letters to refer to the explication of the several problems; hereby raising devils as it were, only to have the credit of laying them, and amusing the ordinary spectators into wonder, because they have not wit enough to understand the juggle. Of these some undertake to profess themselves judicial astrologers, pretending to keep correspondence with the stars, and so from their information can resolve any query; and though it is all but a presumptuous imposture, yet some to be sure will be so great fools as to believe them.

The divines present themselves next; but it may perhaps be most safe to pass them by, and not to touch upon so harsh a string as this subject would afford. Beside, the undertaking may be very hazardous; for they are a sort of men generally very hot and passionate; and should I provoke them, I doubt not would set upon me with a full cry, and force me with shame to recant, which if I stubbornly refuse to do, they will presently brand me for a heretic, and thunder out an excommunication, which is their spiritual weapon to wound such as lift up a hand against them. It is true, no men own a less dependence on me, yet have they reason to confess themselves indebted for no small obligations. For it is by one of my properties, self-love, that they fancy themselves, with their elder brother Paul, caught up into the third heaven, from whence, like shepherds indeed, they look down upon their flock, the laity, grazing as it were, in the vales of the world below. They fence themselves in with so many surrounders of magisterial definitions, conclusions, corollaries, propositions explicit and implicit, that there is no falling in with them; or if they do chance to be urged to a seeming non-plus, yet they find out so many evasions, that all the art of man can never bind them so fast, but that an easy distinction shall give them a starting-hole to escape the scandal of being baffled. They will cut asunder the toughest argument with as much ease as Alexander did the gordian knot; they will thunder out so many rattling terms as shall fright an adversary into conviction. They are exquisitely dexterous in unfolding the most intricate mysteries; they will tell you to a tittle all the successive proceedings of Omnipotence in the creation of the universe; they will explain the precise manner of original sin being derived from our first parents; they will satisfy you in what manner, by what degrees, and in how long a time, our Saviour was conceived in the Virgin's womb, and demonstrate in the consecrated wafer how accidents may subsist without a subject. Nay, these are accounted trivial, easy questions; they have yet far greater difficulties behind, which notwithstanding they solve with as much expedition as the former; as namely, whether supernatural generation requires any instant of time for its acting? whether Christ, as a son, bears a double specifically distinct relation to God the Father, and his virgin mother? whether this proposition is possible to be true, the first person of the Trinity hated the second? whether God, who took our nature upon him in the form of a man, could as well have become a woman, a devil, a beast, a herb, or a stone? and were it so possible that the Godhead had appeared in any shape of an inanimate substance, how he should then have preached his gospel? or how have been nailed to the cross? whether if St. Peter had celebrated the eucharist at the same time our Saviour was hanging on the cross, the consecrated bread would have been transubstantiated into the same body that remained on the tree? whether in Christ's corporal presence in the sacramental wafer, his humanity be not abstracted from his Godhead? whether after the resurrection we shall carnally eat and drink as we do in this life?

There are a thousand other more sublimated and refined niceties of notions, relations, quantities, formalities, quiddities, haeccities, and such like abstrusities, as one would think no one could pry into, except he had not only such cat's eyes as to see best in the dark, but even such a piercing faculty as to see through an inch-board, and spy out what really never had any being. Add to these some of their tenets and opinions, which are so absurd and extravagant, that the wildest fancies of the Stoicks which they so much disdain and decry as paradoxes, seem in comparison just and rational; as their maintaining, that it is a less aggravating fault to kill a hundred men, than for a poor cobbler to set a stitch on the sabbath-day; or, that it is more justifiable to do the greatest injury imaginable to others, than to tell the least lie ourselves. And these subtleties are alchymized to a more refined sublimate by the abstracting brains of their several schoolmen; the Realists, the Nominalists, the Thomists, the Albertists, the Occamists, the Scotists; these are not all, but the rehearsal of a few only, as a specimen of their divided sects; in each of which there is so much of deep learning, so much of unfathomable difficulty, that I believe the apostles themselves would stand in need of a new illuminating spirit, if they were to engage in any controversy with these new divines. St. Paul, no question, had a full measure of faith; yet when he lays down faith to be the substance of things not seen, these men carp at it for an imperfect definition, and would undertake to teach the apostles better logic. Thus the same holy author wanted for nothing of the grace of charity, yet (say they) he describes and defines it but very inaccurately, when he treats of it in the thirteenth chapter of his first epistle to the Corinthians. The primitive disciples were very frequent in administering the holy sacrament, breaking bread from house to house; yet should they be asked of the Terminus a quo and the Terminus ad quern, the nature of transubstantiation? the manner how one body can be in several places at the same time? the difference betwixt the several attributes of Christ in heaven, on the cross, and in the consecrated bread? what time is required for the transubstantiating the bread into flesh? how it can be done by a short sentence pronounced by the priest, which sentence is a species of discreet quantity, that has no permanent punctum? Were they asked (I say) these, and several other confused queries, I do not believe they could answer so readily as our mincing school-men now-a-days take a pride to do. They were well acquainted with the Virgin Mary, yet none of them undertook to prove that she was preserved immaculate from original sin, as some of our divines very hotly contend for. St. Peter had the keys given to him, and that by our Saviour himself, who had never entrusted him except he had known him capable of their manage and custody; and yet it is much to be questioned whether Peter was sensible of that subtlety broached by Scotus, that he may have the key of knowledge effectually for others, who has no knowledge actually in himself. Again, they baptized all nations, and yet never taught what was the formal, material, efficient, and final cause of baptism, and certainly never dreamt of distinguishing between a delible and an indelible character in this sacrament They worshipped in the spirit, following their master's injunction, God is a spirit, and they which worship him, must worship him in spirit, and in truth; yet it does not appear that it was ever revealed to them how divine adoration should be paid at the same time to our blessed Saviour in heaven, and to his picture here below on a wall, drawn with two fingers held out, a bald crown, and a circle round his head. To reconcile these intricacies to an appearance of reason requires three-score years' experience in metaphysics.

Farther, the apostles often mention Grace, yet never distinguish between gratia, gratis data, and gratia gratificans. They earnestly exhort us likewise to good works, yet never explain the difference between Opus operans, and Opus operatum. They very frequently press and invite us to seek after charity, without dividing it into infused and acquired, or determining whether it be a substance or an accident, a created or an uncreated being. They detested sin themselves, and warned others from the commission of it; and yet I am sure they could never have defined so dogmatically, as the Scotists have since done. St. Paul, who in other's judgment is no less the chief of the apostles, than he was in his own the chief of sinners, who being bred at the feet of Gamaliel, was certainly more eminently a scholar than any of the rest, yet he often exclaims against vain philosophy, warns us from doting about questions and strifes of words, and charges us to avoid profane and vain babblings, and oppositions of science falsely so called; which he would not have done, if he had thought it worth his while to have become acquainted with them, which he might soon have been, the disputes of that age being but small, and more intelligible sophisms, in reference to the vastly greater intricacies they are now improved to. But yet, however, our scholastic divines are so modest, that if they meet with any passage in St. Paul, or any other penman of holy writ, which is not so well modelled, or critically disposed of, as they could wish, they will not roughly condemn it, but bend it rather to a favorable interpretation, out of reverence to antiquity, and respect to the holy scriptures; though indeed it were unreasonable to expect anything of this nature from the apostles, whose lord and master had given unto them to know the mysteries of God, but not those of philosophy. If the same divines meet with anything of like nature unpalatable in St. Chrysostom, St. Basil, St. Hierom, or others of the fathers, they will not stick to appeal from their authority, and very fairly resolve that they lay under a mistake. Yet these ancient fathers were they who confuted both the Jews and Heathens, though they both obstinately adhered to their respective prejudices; they confuted them (I say), yet by their lives and miracles, rather than by words and syllogisms; and the persons they thus proselyted were downright honest, well meaning people, such as understood plain sense better than any artificial pomp of reasoning: whereas if our divines should now set about the gaining converts from paganism by their metaphysical subtleties, they would find that most of the persons they applied themselves to were either so ignorant as not at all to apprehend them, or so impudent as to scoff and deride them; or finally, so well skilled at the same weapons, that they would be able to keep their pass, and fence off all assaults of conviction: and this last way the victory would be altogether as hopeless, as if two persons were engaged of so equal strength, that it were impossible any one should overpower the other.

If my judgment might be taken, I would advise Christians, in their next expedition to a holy war, instead of those many unsuccessful legions, which they have hitherto sent to encounter the Turks and Saracens, that they would furnish out their clamorous Scotists, their obstinate Occamists, their invincible Albertists, and all their forces of tough, crabbed and profound disputants: the engagement, I fancy, would be mighty pleasant, and the victory we may imagine on our side not to be questioned. For which of the enemies would not veil their turbans at so solemn an appearance? Which of the fiercest Janizaries would not throw away his scimitar, and all the half-moons be eclipsed by the interposition of so glorious an army?

I suppose you mistrust I speak all this by way of jeer and irony; and well I may, since among divines themselves there are some so ingenious as to despise these captious and frivolous impertinences: they look upon it as a kind of profane sacrilege, and a little less than blasphemous impiety, to determine of such niceties in religion, as ought rather to be the subject of an humble and uncontradicting faith, than of a scrupulous and inquisitive reason: they abhor a defiling the mysteries of Christianity with an intermixture of heathenish philosophy, and judge it very improper to reduce divinity to an obscure speculative science, whose end is such a happiness as can be gained only by the means of practice. But alas, those notional divines, however condemned by the soberer judgment of others, are yet mightily pleased with themselves, and are so laboriously intent upon prosecuting their crabbed studies, that they cannot afford so much time as to read a single chapter in any one book of the whole bible. And while they thus trifle away their misspent hours in trash and babble, they think that they support the Catholic Church with the props and pillars of propositions and syllogisms, no less effectually than Atlas is feigned by the poets to sustain on his shoulders the burden of a tottering world.

Their privileges, too, and authority are very considerable: they can deal with any text of scripture as with a nose of wax, knead it into what shape best suits their interest; and whatever conclusions they have dogmatically resolved upon, they would have them as irrepealably ratified as Solon's laws, and in as great force as the very decrees of the papal chair. If any be so bold as to remonstrate to their decisions, they will bring him on his knees to a recantation of his impudence. They shall pronounce as irrevocably as an oracle, this proposition is scandalous, that irreverent; this has a smack of heresy, and that is bald and improper; so that it is not the being baptised into the church, the believing of the scriptures, the giving credit to St. Peter, St. Paul, St. Hierom, St. Augustin, nay, or St. Thomas Aquinas himself, that shall make a man a Christian, except he have the joint suffrage of these novices in learning,-who have blessed the world no doubt with a great many discoveries, which had never come to light, if they had not struck the fire of subtlety out of the flint of obscurity. These fooleries sure must be a happy employ.

Farther, they make as many partitions and divisions in hell and purgatory, and describe as many different sorts and degrees of punishment as if they were very well acquainted with the soil and situation of those infernal regions. And to prepare a seat for the blessed above, they invent new orbs, and a stately empyrean heaven, so wide and spacious as if they had purposely contrived it, that the glorified saints might have room enough to walk, to feast, or to take any recreation.

With these, and a thousand more such like toys, their heads are more stuffed and swelled than Jove, when he went big of Pallas in his brain, and was forced to use the midwifery of Vulcan's axe to ease him of his teeming burden.

Do not wonder, therefore, that at public disputations they bind their heads with so many caps one over another; for this is to prevent the loss of their brains, which would otherwise break out from their uneasy confinement. It affords likewise a pleasant scene of laughter, to listen to these divines in their hotly managed disputations; to see how proud they are of talking such hard gibberish, and stammering out such blundering distinctions, as the auditors perhaps may sometimes gape at, but seldom apprehend: and they take such a liberty in their speaking of Latin, that they scorn to stick at the exactness of syntax or concord; pretending it is below the majesty of a divine to talk like a pedagogue, and be tied to the slavish observance of the rules of grammar.

Finally, they take a vast pride, among other citations, to allege the authority of their respective master, which word they bear as profound a respect to as the Jews did to their ineffable tetragrammaton, and therefore they will be sure never to write it any otherwise than in great letters, MAGISTER NOSTER; and if any happen to invert the order of the words, and say, noster magister instead of magister noster, they will presently exclaim against him as a pestilent heretic and underminer of the catholic faith.

The next to these are another sort of brainsick fools, who style themselves monks and of religious orders, though they assume both titles very unjustly: for as to the last, they have very little religion in them; and as to the former, the etymology of the word monk implies a solitariness, or being alone; whereas they are so thick abroad that we cannot pass any street or alley without meeting them. Now I cannot imagine what one degree of men would be more hopelessly wretched, if I did not stand their friend, and buoy them up in that lake of misery, which by the engagements of a holy vow they have voluntarily immerged themselves in. But when these sort of men are so unwelcome to others, as that the very sight of them is thought ominous, I yet make them highly in love with themselves, and fond admirers of their own happiness. The first step whereunto they esteem a profound ignorance, thinking carnal knowledge a great enemy to their spiritual welfare, and seem confident of becoming greater proficients in divine mysteries the less they are poisoned with any human learning. They imagine that they bear a sweet consort with the heavenly choir, when they tone out their daily tally of psalms, which they rehearse only by rote, without permitting their understanding or affections to go along with their voice. Among these some make a good profitable trade of beggary, going about from house to house, not like the apostles, to break, but to beg, their bread; nay, thrust into all public-houses, come aboard the passage-boats, get into the travelling waggons, and omit no opportunity of time or place for the craving people's charity; doing a great deal of injury to common highway beggars by interloping in their traffic of alms. And when they are thus voluntarily poor, destitute, not provided with two coats, nor with any money in their purse, they have the impudence to pretend that they imitate the first disciples, whom their master expressly sent out in such an equipage. It is pretty to observe how they regulate all their actions as it were by weight and measure to so exact a proportion, as if the whole loss of their religion depended upon the omission of the least punctilio. Thus they must be very critical in the precise number of knots to the tying on of their sandals; what distinct colours their respective habits, and what stuff made of; how broad and long their girdles; how big, and in what fashion, their hoods; whether their bald crowns be to a hair's-breadth of the right cut; how many hours they must sleep, at what minute rise to prayers, &c. And these several customs are altered according to the humours of different persons and places. While they are sworn to the superstitious observance of these trifles, they do not only despise all others, but are very inclinable to fall out among themselves; for though they make profession of an apostolic charity, yet they will pick a quarrel, and be implacably passionate for such poor provocations, as the girting on a coat the wrong way, for the wearing of clothes a little too darkish coloured, or any such nicety not worth the speaking of.

Some are so obstinately superstitious that they will wear their upper garment of some coarse dog's hair stuff, and that next their skin as soft as silk: but others on the contrary will have linen frocks outermost, and their shirts of wool, or hair. Some again will not touch a piece of money, though they make no scruple of the sin of drunkenness, and the lust of the flesh. All their several orders are mindful of nothing more than of their being distinguished from each other by their different customs and habits. They seem indeed not so careful of becoming like Christ, and of being known to be his disciples, as the being unlike to one another, and distinguishable for followers of their several founders. A great part of their religion consists in their title: some will be called cordeliers, and these subdivided into capuchines, minors, minims, and mendicants; some again are styled Benedictines, others of the order of St. Bernard, others of that of St. Bridget; some are Augustin monks, some Willielmites, and others Jacobists, as if the common name of Christian were too mean and vulgar. Most of them place their greatest stress for salvation on a strict conformity to their foppish ceremonies, and a belief of their legendary traditions; wherein they fancy to have acquitted themselves with so much of supererogation, that one heaven can never be a condign reward for their meritorious life; little thinking that the Judge of all the earth at the last day shall put them off, with a who hath required these things at your hands; and call them to account only for the stewardship of his legacy, which was the precept of love and charity. It will be pretty to hear their pleas before the great tribunal: one will brag how he mortified his carnal appetite by feeding only upon fish: another will urge that he spent most of his time on earth in the divine exercise of singing psalms: a third will tell how many days he fasted, and what severe penance he imposed on himself for the bringing his body into subjection: another shall produce in his own behalf as many ceremonies as would load a fleet of merchant-men: a fifth shall plead that in threescore years he never so much as touched a piece of money, except he fingered it through a thick pair of gloves: a sixth, to testify his former humility, shall bring along with him his sacred hood, so old and nasty, that any seaman had rather stand bare headed on the deck, than put it on to defend his ears in the sharpest storms: the next that comes to answer for himself shall plead, that for fifty years together, he had lived like a sponge upon the same place, and was content never to change his homely habitation: another shall whisper softly, and tell the judge he has lost his voice by a continual singing of holy hymns and anthems: the next shall confess how he fell into a lethargy by a strict, reserved, and sedentary life: and the last shall intimate that he has forgot to speak, by having always kept silence, in obedience to the injunction of taking heed lest he should have offended with his tongue. But amidst all their fine excuses our Saviour shall interrupt them with this answer, Woe unto you, scribes and pharisees, hypocrites, verily I know you not; I left you but one precept, of loving one another, which I do not hear any one plead he has faithfully discharged: I told you plainly in my gospel, without any parable, that my father's kingdom was prepared not for such as should lay claim to it by austerities, prayers, or fastings, but for those who should render themselves worthy of it by the exercise of faith, and the offices of charity: I cannot own such as depend on their own merits without a reliance on my mercy: as many of you therefore as trust to the broken reeds of your own deserts may even go search out a new heaven, for you shall never enter into that, which from the foundations of the world was prepared only for such as are true of heart. When these monks and friars shall meet with such a shameful repulse, and see that ploughmen and mechanics are admitted into that kingdom, from which they themselves are shut out, how sneakingly will they look, and how pitifully slink away? Yet till this last trial they had more comfort of a future happiness, because more hopes of it than any other men. And these persons are not only great in their own eyes, but highly esteemed and respected by others, especially those of the order of mendicants, whom none dare to offer any affront to, because as confessors they are intrusted with all the secrets of particular intrigues, which they are bound by oath not to discover; yet many times, when they are almost drunk, they cannot keep their tongue so far within their head, as not to be babbling out some hints, and shewing themselves so full, that they are in pain to be delivered. If any person give them the least provocation they will sure to be revenged of him, and in their next public harangue give him such shrewd wipes and reflections, that the whole congregation must needs take notice at whom they are levelled; nor will they ever desist from this way of declaiming, till their mouth be stopped with a bribe to hold their tongue. All their preaching is mere stage-playing, and their delivery the very transports of ridicule and drollery. Good Lord! how mimical are their gestures? What heights and falls in their voice? What toning, what bawling, what singing, what squeaking, what grimaces, making of mouths, apes' faces, and distorting of their countenance; and this art of oratory as a choice mystery, they convey down by tradition to one another. The manner of it I may adventure thus farther to enlarge upon. First, in a kind of mockery they implore the divine assistance, which they borrowed from the solemn custom of the poets: then if their text suppose be of charity, they shall take their exordium as far off as from a description of the river Nile in Egypt; or if they are to discourse of the mystery of the Cross, they shall begin with a story of Bell and the Dragon; or perchance if their subject be of fasting, for an entrance to their sermon they shall pass through the twelve signs of the zodiac; or lastly, if they are to preach of faith, they shall address themselves in a long mathematical account of the quadrature of the circle. I myself once heard a great fool (a great scholar I would have said) undertaking in a laborious discourse to explain the mystery of the Holy Trinity; in the unfolding whereof, that he might shew his wit and reading, and together satisfy itching ears, he proceeded in a new method, as by insisting on the letters, syllables, and proposition, on the concord of noun and verb, and that of noun substantive, and noun adjective; the auditors all wondered, and some mumbled to themselves that hemistitch of Horace,

Why all this needless trash?

But at last he brought it thus far, that he could demonstrate the whole Trinity to be represented by these first rudiments of grammar, as clearly and plainly as it was possible for a mathematician to draw a triangle in the sand: and for the making of this grand discovery, this subtle divine had plodded so hard for eight months together, that he studied himself as blind as a beetle, the intenseness of the eye of his understanding overshadowing and extinguishing that of his body; and yet he did not at all repent him of his blindness, but thinks the loss of his sight an easy purchase for the gain of glory and credit.

I heard at another time a grave divine, of fourscore years of age at least, so sour and hard-favoured, that one would be apt to mistrust that it was Scotus Redivivus; he taking upon him to treat of the mysterious name, JESUS, did very subtly pretend that in the very letters was contained, whatever could be said of it: for first, its being declined only with three cases, did expressly point out the trinity of persons, then that the nominative ended in S, the accusative in M, and the ablative in U, did imply some unspeakable mystery, viz. , that in words of those initial letters Christ was the summus, or beginning, the medius, or middle, and the ultimus, or end of all things. There was yet a more abstruse riddle to be explained, which was by dividing the word JESUS into two parts, and separating the S in the middle from the two extreme syllables, making a kind of pentameter, the word consisting of five letters: and this intermedial S being in the Hebrew alphabet called sin, which in the English language signifies what the Latins term peecatum, was urged to imply that the holy Jesus should purify us from all sin and wickedness. Thus did the pulpiteer cant, while all the congregation, especially the brotherhood of divines, were so surprised at his odd way of preaching, that wonder served them, as grief did Niobe, almost turned them into stones. I among the rest (as Horace describes Priapus viewing the enchantments of the two sorceresses, Canidia and Sagane) could no longer contain, but let fly a cracking report of the operation it had upon me. These impertinent introductions are not without reason condemned; for of old, whenever Demosthenes among the Greeks, or Tully among the Latins, began their orations with so great a digression from the matter in hand, it was always looked upon as improper and unelegant, and indeed, were such a long-fetched exordium any token of a good invention, shepherds and ploughmen might lay claim to the title of men of greatest parts, since upon any argument it is easiest for them to talk what is least to the purpose. These preachers think their preamble (as we may well term it), to be the most fashionable, when it is farthest from the subject they propose to treat of, while each auditor sits and wonders what they drive at, and many times mutters out the complaint of Virgil:—

Whither does all this jargon tend? In the third place, when they come to the division of their text, they shall give only a very short touch at the interpretation of the words, when the fuller explication of their sense ought to have been their only province. Fourthly, after they are a little entered, they shall start some theological queries, far enough off from the matter in hand, and bandy it about pro and con till they lose it in the heat of scuffle. And here they shall cite their doctors invincible, subtle, seraphic, cherubic, holy, irrefragable, and such like great names to confirm their several assertions. Then out they bring their syllogisms, their majors, their minors, conclusions, corollaries, suppositions, and distinctions, that will sooner terrify the congregation into an amazement, than persuade them into a conviction. Now comes the fifth act, in which they must exert their utmost skill to come off with applause. Here therefore they fall a telling some sad lamentable story out of their legend, or some other fabulous history, and this they descant upon allegorically, tropologically, and analogically; and so they draw to a conclusion of their discourse, which is a more brain-sick chimera than ever Horace could describe in his De Arte Poetica, when he began:—

Humano Capitis &c. Their praying is altogether as ridiculous as their preaching; for imagining that in their addresses to heaven they should set out in a low and tremulous voice, as a token of dread and reverence, they begin therefore with such a soft whispering as if they were afraid any one should overhear what they said; but when they are gone a little way, they clear up their pipes by degrees, and at last bawl out so loud as if, with Baal's priests, they were resolved to awake a sleeping god; and then again, being told by rhetoricians that heights and falls, and a different cadency in pronunciation, is a great advantage to the setting off any thing that is spoken, they will sometimes as it were mutter their words inwardly, and then of a sudden hollo them out, and be sure at last, in such a flat, faltering tone as if their spirits were spent, and they had run themselves out of breath. Lastly, they have read that most systems of rhetoric treat of the art of exciting laughter; therefore for the effecting of this they will sprinkle some jests and puns that must pass for ingenuity, though they are only the froth and folly of affectedness. Sometimes they will nibble at the wit of being satyrical, though their utmost spleen is so toothless, that they suck rather than bite, tickle rather than scratch or wound: nor do they ever flatter more than at such times as they pretend to speak with greatest freedom.

Finally, all their actions are so buffoonish and mimical, that any would judge they had learned all their tricks of mountebanks and stage-players, who in action it is true may perhaps outdo them, but in oratory there is so little odds between both, that it is hard to determine which seems of longest standing in the schools of eloquence.

Yet these preachers, however ridiculous, meet with such hearers, who admire them as much as the people of Athens did Demosthenes, or the citizens of Rome could do Cicero: among which admirers are chiefly shopkeepers, and women, whose approbation and good opinion they only court; because the first, if they are humoured, give them some snacks out of unjust gain; and the last come and ease their grief to them upon all pinching occasions, especially when their husbands are any ways cross or unkind.

Thus much I suppose may suffice to make you sensible how much these cell-hermits and recluses are indebted to my bounty; who when they tyrannize over the consciences of the deluded laity with fopperies, juggles, and impostures, yet think themselves as eminently pious as St. Paul, St. Anthony, or any other of the saints; but these stage-divines, not less ungrateful dis-owners of their obligations to folly, than they are impudent pretenders to the profession of piety, I willingly take my leave of, and pass now to kings, princes, and courtiers, who paying me a devout acknowledgment, may justly challenge back the respect of being mentioned and taken notice of by me. And first, had they wisdom enough to make a true judgment of things, they would find their own condition to be more despicable and slavish than that of the most menial subjects. For certainly none can esteem perjury or parricide a cheap purchase for a crown, if he does but seriously reflect on that weight of cares a princely diadem is loaded with. He that sits at the helm of government acts in a public capacity, and so must sacrifice all private interest to the attainment of the common good; he must himself be conformable to those laws his prerogative exacts, or else he can expect no obedience paid them from others; he must have a strict eye over all his inferior magistrates and officers, or otherwise it is to be doubted they will but carelessly discharge their respective duties. Every king, within his own territories, is placed for a shining example as it were in the firmament of his wide-spread dominions, to prove either a glorious star of benign influence, if his behaviour be remarkably just and innocent, or else to impend as a threatening comet, if his blazing power be pestilent and hurtful. Subjects move in a darker sphere, and so their wanderings and failings are less discernible; whereas princes, being fixed in a more exalted orb, and encompassed with a brighter dazzling lustre, their spots are more apparently visible, and their eclipses, or other defects, influential on all that is inferior to them. Kings are baited with so many temptations and opportunities to vice and immorality, such as are high feeding, liberty, flattery, luxury, and the like, that they must stand perpetually on their guard, to fence off those assaults that are always ready to be made upon them. In fine, abating from treachery, hatred, dangers, fear, and a thousand other mischiefs impending on crowned heads, however uncontrollable they are this side heaven, yet after their reign here they must appear before a supremer judge, and there be called to an exact account for the discharge of that great stewardship which was committed to their trust If princes did but seriously consider (and consider they would if they were but wise) these many hardships of a royal life, they would be so perplexed in the result of their thoughts thereupon, as scarce to eat or sleep in quiet But now by my assistance they leave all these cares to the gods, and mind only their own ease and pleasure, and therefore will admit none to their attendance but who will divert them with sport and mirth, lest they should otherwise be seized and damped with the surprisal of sober thoughts. They think they have sufficiently acquitted themselves in the duty of governing, if they do but ride constantly a hunting, breed up good race-horses, sell places and offices to those of the courtiers that will give most for them, and find out new ways for invading of their people's property, and hooking in a larger revenue to their own exchequer; for the procurement whereof they will always have some pretended claim and title; that though it be manifest extortion, yet it may bear the show of law and justice: and then they daub over their oppression with a submissive, flattering carriage, that they may so far insinuate into the affections of the vulgar, as they may not tumult nor rebel, but patiently crouch to burdens and exactions. Let us feign now a person ignorant of the laws and constitutions of that realm he lives in, an enemy to the public good, studious only for his own private interest, addicted wholly to pleasures and delights, a hater of learning, a professed enemy to liberty and truth, careless and unmindful of the common concerns, taking all the measures of justice and honesty from the false beam of self-interest and advantage, after this hang about his neck a gold chain, for an intimation that he ought to have all virtues linked together; then set a crown of gold and jewels on his head, for a token that he ought to overtop and outshine others in all commendable qualifications; next, put into his hand a royal sceptre for a symbol of justice and integrity; lastly, clothe him with purple, for an hieroglyphic of a tender love and affection to the commonwealth. If a prince should look upon this portraiture, and draw a comparison between that and himself, certainly he would be ashamed of his ensigns of majesty, and be afraid of being laughed out of them.

Next to kings themselves may come their courtiers, who, though they are for the most part a base, servile, cringing, low-spirited sort of flatterers, yet they look big, swell great, and have high thoughts of their honour and grandeur. Their confidence appears upon all occasions; yet in this one thing they are very modest, in that they are content to adorn their bodies with gold, jewels, purple, and other glorious ensigns of virtue and wisdom, but leave their minds empty and unfraught; and taking the resemblance of goodness to themselves, turn over the truth and reality of it to others. They think themselves mighty happy in that they can call the king master, and be allowed the familiarity of talking with him; that they can volubly rehearse his several tides of august highness, supereminent excellence, and most serene majesty, that they can boldly usher in any discourse, and that they have the complete knack of insinuation and flattery; for these are the arts that make them truly genteel and noble. If you make a stricter enquiry after their other endowments, you shall find them mere sots and dolts. They will sleep generally till noon, and then their mercenary chaplains shall come to their bed-side, and entertain them perhaps with a short morning prayer. As soon as they are drest they must go to breakfast, and when that is done, immediately to dinner. When the cloth is taken away, then to cards, dice, tables, or some such like diversion. After this they must have one or two afternoon banquets, and so in the evening to supper. When they have supped then begins the game of drinking; the bottles are marshalled, the glasses ranked, and round go the healths and bumpers till they are carried to bed. And this is the constant method of passing away their hours, days, months, years, and ages. I have many times took great satisfaction by standing in the court, and seeing how the tawdry butterflies vie upon one another: the ladies shall measure the height of their humours by the length of their trails, which must be borne up by a page behind. The nobles justle one another to get nearest to the king's elbow, and wear gold chains of that weight and bigness as require no less strength to carry than they do wealth to purchase.

And now for some reflections upon popes, cardinals, and bishops, who in pomp and splendour have almost equalled if not outgone secular princes. Now if any one consider that their upper crotchet of white linen is to signify their unspotted purity and innocence; that their forked mitres, with both divisions tied together by the same knot, are to denote the joint knowledge of the Old and New Testament; that their always wearing gloves, represents their keeping their hands clean and undented from lucre and covetousness; that the pastoral staff implies the care of a flock committed to their charge; that the cross carried before them expresses their victory over all carnal affections; he (I say) that considers this, and much more of the like nature, must needs conclude they are entrusted with a very weighty and difficult office. But alas, they think it sufficient if they can but feed themselves; and as to their flock, either commend them to the care of Christ himself, or commit them to the guidance of some inferior vicars and curates; not so much as remembering what their name of bishop imports, to wit, labour, pains, and diligence, but by base simoniacal contracts, they are in a profane sense Episcopi, i.e. , overseers of their own gain and income.