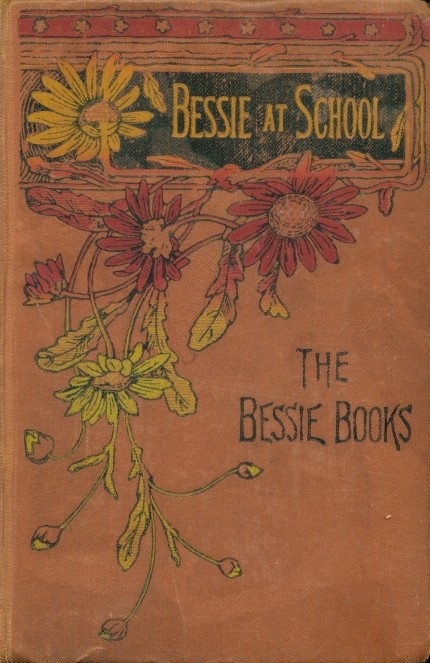

Bessie at school

Play Sample

CHAPTER X.

A LITTLE LIGHT.

Bessie would have liked to have had a word or two with Kate during recess, but when she peeped into the other room, she saw all the rest of the girls gathered around her; and not caring to talk, or to be talked to by them, she ran away again without being noticed, and followed her sister down to the music-room.

The girls of the older class were all in a state of great excitement over the trouble of the morning. Some were anxious, some pitying, some saying that Mrs. Ashton was making a great fuss about a trifle. Fanny Berry, who had been weeping and sobbing at intervals through all the lesson-hours, was now drowned in a fresh flood of tears, and bewailing her hard fate in having to go to Mrs. Ashton "for a lecture" after school.

"And I suppose she'll complain to my father too," she moaned. "She has been saying she would do so the next time any of the masters reported me; and now she'll tell him this—the hateful old thing! —and he won't let me go to the birthday party at my aunt's. O Kate, why did you tell? You promised you would not—you promised! Of course I could not let Mrs. Ashton go on giving you more than your own share of blame, and so I was forced to speak. It's just as Mary said it would be if any one told their own part. It must needs bring the rest into trouble; and after we two had denied it too! You ought to have stood by us."

"Were you in it too, Mary?" asked Ella Leroy; and she, as well as most of the others, looked at Mary in shocked surprise. To some of them it was no very great matter that the four who had had any share in the accident to the clock should shrink from confessing it, or even keep silence when Mrs. Ashton had asked who had done it; but a deliberate denial of their guilt was quite another thing. They deservedly blamed Fanny for her first falsehood; but they had the feeling that she had half redeemed her sin when she had, at the risk of such shame and mortification to herself, acknowledged that, and her former fault, rather than allow Kate to receive a more severe reproof than she merited. But Mary, who it seemed had been as much to blame as the others, had not even then been shamed into telling the truth, and had still let Mrs. Ashton believe her innocent.

She was heartily ashamed of it now; but she did not choose to let that be seen, and carried matters with a high hand, tossing her head and declaring that she was "not going to be such a fool as to get herself into difficulty just because Kate and Fanny chose to do it." She reproached Kate bitterly for breaking her promise, and so did Fanny; both saying that all would have been well if she had not done so.

"I am sorry," said Kate, taking their upbraidings with a meekness quite unusual in her. "I am very sorry for the punishment I have brought upon you, girls; but not sorry that I did not—tell a lie."

"You should have thought of that before," said Mary, "and not let Fanny and me tell what you so elegantly call a lie, and then set yourself up for being so truthful."

"I do not set myself up for being truthful," said Kate, colouring deeply; "at least I have not, but, with God's help, I will from this day," and she looked steadily into Mary's angry face. "I wish—oh, how I wish! —I had spoken when Mrs. Ashton asked the general question of the whole class, or that she had asked me first; and, even to the moment when she called my name, I meant to deny it—but I could not with Bessie Bradford's eyes upon me."

"Bessie Bradford! little Bessie! and what had she to do with it?" asked two or three of the girls.

"She had this much to do with it," said Kate, "that she was in the room yesterday when the clock was broken; and when we resolved to hide it, we tried to make her as deceitful as ourselves; but we tempted, threatened, and promised in vain. She was not to be frightened into wrong for fear of the consequences of doing right; and, as Julia said, she, baby as she is, shamed us all. Yes, shamed me at least, and made me feel what a mean coward I was beside her."

"You are a coward, to be sure, if you are afraid of Bessie Bradford, or what she could do or say," said Mary, pretending to misunderstand Kate.

"I was not afraid of anything she would say or do," said Kate, not noticing the contemptuous tone; "but of what she would think of me, of losing her affection and respect. But"—she went on more slowly, as if half ashamed, yet determined to speak out—"that was not all I was afraid of."

"What else, then?" asked Mary,

"Of offending Bessie's Master," said Kate.

She felt it was a bold avowal to make in the presence of all her classmates—for her who had always been so reckless and careless, sometimes even irreverent; but she said it, and that with a gravity which showed she meant it, and that it was no light feeling which had called it forth.

It was received in astonished silence by the rest. Words like these were so new from Kate, and there was no need for any one of them to ask what Master Bessie served. The daily life of the little child showed to all about her whose work she delighted to do in her own simple way, which knew no other rule than what would be pleasing and true to Him.

"But, Kate," said Ella presently, "you don't mean that you call Him your Master?"

"No," said Kate; "I pretend to nothing of the sort, and you know it; but when I saw Bessie waiting for my answer, and knew of what and of whom she was thinking, I could not help feeling that another ear was listening and waiting too; and so—I dared not. There!" and Kate drew up her head defiantly. "You may laugh at me, you may sneer at me, you may call this humbug; but it is what I felt, and why I answered as I did; and I am not ashamed to own it. I tell you because you feel, some of you, that I have meanly broken my promise. It was a mean thing to make it; it would have been meaner to keep it than it was to break it; and it was better to be false to that promise than false to my own conscience and to God. But I never meant to betray any one but myself; and, Fanny, I am only too sorry if you are worse punished for what I have done;" and she held out her hand to her schoolmate.

Fanny was vexed as well as distressed, but she could not resist Kate's frankness; and she laid her hand in hers, saying, "I suppose I ought not to complain; it was my fault in the first place."

Not one of the girls had laughed, not one had sneered; not one but had been more or less touched by Kate's unusual earnestness, and the way in which she had set herself to atone for her past fault.

"Kate would think we were all perfect, if we took Bessie Bradford for our pattern," said one, half jokingly, but not unkindly.

"Not exactly," said Kate, smiling; "but I believe if we took Bessie's standard of right and wrong, and tried to follow it as truly as she does, we should not go far out of the way. I would not be ashamed to have it said that I had profited by such an example. If her light is a little one, it burns very clearly."

"But if Bessie had been guilty herself, do you believe it would have been so impossible to tempt her?" said Fanny. "If she had expected to be punished, would she have been so ready to confess?"

"Have you forgotten the japonica?" asked Kate. "I thought of that too."

"What japonica?" said Fanny.

"Oh, true! you were not at school that day," answered Kate, laughing at the recollection. "I will tell you."

Now this was the story, and, as I know more about it than Kate, I will tell you myself, instead of giving it in her words; and to do this, I must go some way back.

Miss Ashton was in the habit of giving a few moments of recreation during the morning to her four younger scholars. Sometimes, if the day were pleasant, she let them run on the piazza or in the old garden; and, when she did this, she used to ring for Marcia, the coloured servant-girl, to come and help the children put on their wrappings. Bessie did not like this girl, she could not tell exactly why; but she had, as yet, never allowed this dislike to make her rude or unkind to Marcia.

But one day, when she was down in the music-room with Maggie and Miss Ashton, she saw Marcia do something which she thought gave her good reason for her dislike. The cook had set a dish of stewed pears on the edge of the piazza to cool; and Bessie saw Marcia steal out from the kitchen, and take three of the pears, swallowing them, one after the other, as fast as possible, and then run away. She told Maggie of this, but they agreed they would not "tell tales about it" to any one else.

From that time Bessie would never suffer Marcia to do anything for her. She would rather stay in the house than allow the girl to put on her cloak or shoes; rather go thirsty than take a glass of water from her hand.

One morning, about a week before the affair of the clock, Harry said at breakfast, "Papa, the police caught a lot of burglars round in the next street last night."

"What are burglars?" asked Maggie.

"Thieves and robbers, who go about breaking into people's houses, and taking what does not belong to them," said Harry.

"And did they come into the next street to ours?" asked timid Maggie, with wide-open eyes.

"Yes; but you needn't be afraid. They wouldn't take you, any way; and they most always get found out, and taken to prison," said Harry, thinking more of comforting Maggie than of sticking closely to facts.

"We know a burglar that hasn't been found out, and taken to prison; don't we, Maggie?" said Bessie gravely. "She burgles very badly too, and when she has done, she licks her fingers."

The boys shouted, and the grown people could not help laughing too.

"Don't be vexed, little daughter," said papa, as he saw the cloud of displeasure overshadow Bessie's face. "Come and sit here on my knee, and tell us what your burglar did."

"She's not mine at all, papa; and I am glad she is not, for I don't like her, and she is wicked too. Mrs. Ashton thinks she is pretty good, but she went and burgled three pears out of the dish, and ate them right up."

The boys were more amused than ever, and kept up their laughter till their father told them the joke had lasted long enough; but he had so much difficulty in keeping his own face straight as he thought of Bessie's indignant tone and look, and of the way in which she had used the word, that he did not try to explain its proper meaning to her just then; and, smiling, he kissed her, and said gently, "If she goes on doing such things, Bessie, she will be found out in time, and punished too, though she may not be taken to prison."

When the little girls went to school, they found Mrs. Ashton in the cloak-room, tending a stand of plants which she had just placed in the window.

"I hope none of you will hurt my plants," she said. "They need the sun, and this is the best place for them, so I shall trust that you will be careful and not touch them. There, I shall put this bench here, and none of you must go on the other side of it. I would not have them broken for a great deal, especially this white japonica."

The one pure white blossom upon the plant was certainly a beauty, and the children did not wonder that Mrs. Ashton was choice of it.

The day was so mild and lovely that, when Miss Ashton sent the little ones out for their fifteen minutes' play, she told them that they had all better put their things on, and run out in the fresh air; and, as usual on such occasions, she rang for Marcia to come and help them.

Bessie would not let the coloured girl do anything for her; but, as she was very anxious to go in the garden with her playmates, she tried her best to put on her own things. With Belle's help she contrived to put on her hat and cloak; but, even with the aid of the other two, it was found next to impossible to manage those troublesome leggings with all their numberless buttons; and it took so long that, at last, Miss Ashton, hearing their voices, came to tell them that they were losing too much time, and must go down at once.

She found Bessie sitting on the bench which stood before the flowers, and the other three little girls all tugging and pulling away at one legging, while Marcia stood leaning against the door and laughing.

"Bessie," said the lady, "why do you not let Marcia do that for you? I want you to go down right away."

"I don't want Marcia to do it," answered Bessie.

"You must let her, or else stay in the house," said Miss Ashton. "I cannot have the others kept from their play to help you."

"We like to help her," said Belle.

"You must go out at once, Bessie. Will you let Marcia help you, or no?"

"No," said Bessie, with a pout; for she was not in a good humour that morning, and she felt as if her dislike to Marcia was very strong. "She shan't touch me, and I'd rather stay in the house."

"Very well," said Miss Ashton. "I am sorry you are so naughty, but the rest must go."

She sent the others away, and Marcia after them, and went back to her room, leaving Bessie alone. The little girl sat still for two or three moments, feeling very angry, and swelling with pride and impatience; thinking that Miss Ashton was very unkind, and Marcia, oh, so wicked! and that she wished she had never come to school, even for Maggie's sake.

Presently she saw the coloured girl's head peeping round the door at her. Marcia was good-natured, if she was not very trustworthy; and she felt sorry when she thought of Bessie sitting there all alone, and so she had come back to see if the little lady would not be glad of her help after all.

"Go away," said Bessie angrily.

"Don't little miss want Marcia put 'em on now?" said Marcia.

"No, I don't; go away," said Bessie; and as she spoke, she raised one of her leggings which she held in her hand, as though she would have thrown it at Marcia. The girl laughed and disappeared, leaving Bessie feeling, the next instant, very much ashamed; and then a very sad thing happened.

The legging had caught on something behind her, and she turned her head to see what held it, giving it at the same time an impatient little pull. One of the buttons had caught upon the stem of the japonica; and alas, alas! as Bessie twitched it away, the white blossom was broken short off, and fell upon the floor! Ah, how frightened the poor child was when she saw what she had done! The flower had fallen behind the window-curtain, where it might have lain for a long time without being noticed; and, with all the people who were going and coming in this room, it might easily have seemed that it had been broken without the knowledge of the person who did it. But no thought of concealment entered Bessie's little heart; and, after one moment's pause of astonishment and alarm, she picked up the broken flower, and ran with it to Mrs. Ashton's room.

The lady was just preparing to hear a recitation, when a fumbling was heard at the lock, as though a small hand were trying to turn it; then the door opened, and Bessie appeared. One hand was held behind her; and she stood looking up at Mrs. Ashton, with her colour coming and going.

"Well, Bessie, what is it?" asked Mrs. Ashton.

"Ma'am," said Bessie, and then she stopped, and drew a long breath.

"Have you any message?" asked Mrs. Ashton, who was near-sighted, and did not notice the expression of the child's face.

"No, ma'am," said Bessie; "but"—

"Then run away. Why do you interrupt us now?"

"Because I have to make trouble for you, ma'am," said the poor little thing.

"That is just what I do not wish you to do. If you have anything to say, you may tell me by and by."

"I'll have to tell you now, or you might think somebody else did it," said Bessie; and, as she spoke, she drew her hand from behind her, and showed the broken flower. "I'm very sorry, ma'am, but I broke your flower."

Mrs. Ashton's pale face flushed angrily, then grew calm again.

"How did that happen, Bessie? Did I not tell you not to touch the flowers?"

"Yes, ma'am," answered the child, the tears beginning to run slowly down her cheeks; "and I didn't mean to touch them, and I didn't go on the other side of the bench. It was with my legging—I don't quite know how; but it was 'cause I was naughty. I was mad with Marcia, and was going to throw my legging at her; and somehow it knocked the flower and broke it. But I know I did it; and I thought I ought to tell you very quick, or you might think it was Marcia, or some one else."

"I am glad you are so honest, Bessie," said Mrs. Ashton. "Put the flower down, and I will talk to you about it by and by."

Bessie laid the japonica on the table, and turned to go, then turned back again.

"Ma'am," she said, "if you are going to scold me, would you have objections to do it now? I guess the young ladies would just as lief wait, and I don't like to think about it so long."

The young ladies had all been listening to the child, and feeling great sympathy for her in her trouble; while they could not help admiring her straightforward truthfulness and generous fear lest another should be blamed for her fault; but at this speech every book in the class went up before the owner's face to hide the smiles which could not be repressed. Even the corners of Mrs. Ashton's grave mouth gave way a little.

"I am not going to scold you, Bessie," she said. "I will never scold any one who truthfully confesses an accident; so I shall say no more about the flower. But what makes you so pettish and unkind to Marcia? You do not behave well to her. Has she done anything to you?"

"No, ma'am, not to me," said Bessie, drying her tears.

"To Maggie or Belle then? I know she is mischievous sometimes, and I will not let her annoy you; but you must not behave so to her."

"She did not annoy any of us, ma'am. She is very good to us, only I don't let her help me."

"Why not, if she does not trouble you?"

"I can't approve her; she is too wicked," said Bessie.

"What makes you think so?" asked the lady, who saw there was something at the bottom of all this, and thought it better to settle the difficulty at once.

"She is a burglar," said Bessie solemnly.

"A what?" exclaimed Mrs. Ashton.

Now, as we know, our Maggie and Bessie were both fond of a long word; and as soon as they understood, or thought they understood, the meaning of one, put it in use on every occasion. And, besides, Bessie thought it sounded better to ears polite to use the new one she had heard that morning, than it did to say thief or steal; so she answered,—

"She is, ma'am. Maybe you don't know it, but she is a burglar. I saw her burgle three pears out of your dish; and she put her fingers in the dish too, and then licked every one of them."

The emphatic tone of disgust in which these last words were uttered, and the expression of the child's face, told that the uncleanliness of the trick, as well as its sinfulness, had gone far to horrify her.

The whole thing—look, tone, and words—was irresistible. All discipline was at an end; and Mrs. Ashton herself could not help joining in the merry laugh that was raised by the class.

Bessie would have been angry again; but the thought of her late passion, its sad consequences, and her present repentance, kept her temper in check, and she stood silent. Mrs. Ashton recollected herself, and raised a warning finger to the amused line of girls before her, as she saw Bessie's disturbed face; and, drawing the child to her, she kissed the grieved lips, and said kindly,—

"I am sorry Marcia did such a naughty thing, Bessie; but she has not been as well taught as some of us, and we all do wrong sometimes, and need forgiveness from one another as well as from God."

"Yes, ma'am," answered Bessie meekly, "and I was very naughty to be so angry. Please to 'scuse me, and I'll try not to be cross to Marcia again. And I'm very sorry about your flower."

"I shall not care about my flower if it serves to teach you a lesson," said the lady. "That is quite forgiven; and you need not distress yourself over it. Now you may go."

Bessie drew Mrs. Ashton's head down to her.

"And may I go and tell Marcia I am sorry I was so angry with her?" she whispered.

"Certainly," said Mrs. Ashton; and Bessie went away.

Mrs. Ashton waited a moment till her class had settled into quiet, and then, taking up the broken flower, she said,—

"I do not regret the time spared from the recitation which this little incident has occupied. The loss of my flower has furnished lessons to more than little Bessie; lessons which we will all do well to lay to heart, and which may prove of far more value than that which we should have learned from our books. I trust they may not be lost."

So much of all this as had come to her own knowledge Kate told to Fanny, who laughed with the others, but found in the story fresh cause to feel ashamed that she had been so far outdone in truth and generosity by a little child.

The dreaded interview with Mrs. Ashton took place after school. Kate and Fanny found her more grieved than angry, more hurt at their deceit and want of confidence in her than at the injury to her clock. She talked long and seriously to them, not failing to point out the difference between their conduct and that of little Bessie; and she was both touched and gratified when Kate told, not without tears, of the part they had acted towards the child, and of the influence of the little one's example in leading her to confession and repentance.

Mrs. Ashton told the girls that she should inflict no further punishment upon them than an apology to Monsieur Gaufrau, and a confession of the deception that had been practised upon him; and she was still better pleased when Kate told her that this had already been done, and that she had, in her own name and Fanny's, begged his pardon before the whole class.

"For," said she, with many blushes, "as long as I had started on the right track, I thought I would not stop half-way."

"Then do not stop half-way, and do not turn back, my child," said Mrs. Ashton, holding out her hand to the young girl; "you have farther, much farther to go, Kate, before you reach the goal. Oh, take heed that your steps turn neither to the right nor to the left from the way of truth and uprightness."

CHAPTER XI.

ABOUT OUR FATHER'S WORK.

"Up, up," said the baby, "up, up."

Baby sat upon the hearth-rug in her mother's room, with her playthings about her; and Maggie sat beside her, writing away upon her slate.

If you had asked Maggie what she was doing, she would probably have said, "Taking care of baby;" for that was what her mother had asked her to do, and what she really believed herself to be doing. But perhaps baby would have given a different opinion.

"Up, up, wee, wee," said the little one again, pulling away at Maggie's skirt.

"Yes, darling, by and by. Oh, see, see baby's pretty dolly!" and, putting the doll in her little sister's lap, Maggie turned again to her slate. Baby took dolly by the heels and thumped her head upon the floor—it was well dolly was not subject to headaches; then she scolded her, then kissed her, and sung and petted her to sleep, then put the doll's cool china head in her own heated little mouth; and at last, tiring of all these, threw her down, and took hold of Maggie again with that pitiful, beseeching, "Up, up."

"Now, Maggie, dear, just put by your writing, and take baby up, and tell her 'the little pig that went to market,'" said nurse. "She's fretful with her teeth, and they hurt her so this morning. Yes, my pet; your Mammy will take ye, and tell ye pigs without end, as soon as she gets this naughty boy dressed."

The naughty boy was Frankie, who had undertaken to give baby's woolly lamb a shower-bath, and, not being able to reach the faucet, had climbed into the bath-tub, where he had turned it to such purpose as to shower, not only the lamb, but himself from head to foot. Frankie was too well used to the consequences of such pranks to mind them very much; but, as usual, he had chosen a time when it was not very convenient to attend to him.

This was Saturday morning. Jane was sweeping the nursery, nurse sorting the clean clothes, Mrs. Bradford petting her fretful baby, and Maggie very busy over that prize composition; while Bessie was in her own room, dressing the dolls and putting the baby-house in order; for Belle Powers and Lily Norris were coming to spend the day, and all must be ready for them. So every one was very busy, and that, of course, must be the time for Frankie to get into mischief.

Then, just as nurse began to take off his wet clothes, a lady came to see Mrs. Bradford on business, and she had to go down-stairs; so, putting baby down on the rug, mamma told Maggie to amuse her till she came back. But Maggie, having brought some toys for her little sister, thought she had done enough, and went on with her writing.

But baby was not in a mood to amuse herself. She wanted to be taken up, and told that wonderful story about the well-known family of little pigs, which mamma had been telling upon her tiny fingers when she was called away.

And Maggie?

Maggie was trying to make two things agree, her duty and her inclination. Sometimes these go very well together; but on this occasion they did not. Maggie strove to persuade herself that the last was the first; but neither baby, nurse, nor her conscience would let her deceive herself so, and she did not feel well pleased with either of the three monitors.

"I'll take her when I've finished this idea," said Maggie. "There, baby, play with the pretty blocks."

"Bad bocky," said baby, striking out with her little foot at the pile of blocks before her. Just then Bessie peeped around the door; and seeing that the baby was restless and discontented, and nurse busy, she came to do what she could for her little sister's amusement.

"Bessie make her nice house," she said, thinking that was what the child wanted; and she began piling the blocks on one another in a tower, which baby was to have the pleasure of knocking down when it should be finished, talking to her the while in a coaxing, chirruping voice.

Baby put three fingers into her mouth, and sat watching Bessie for a few moments, when, suddenly bethinking herself once more of the adventures of those famous pigs, and of the coveted seat upon Maggie's lap, she dashed over the half-built tower, and, turning again towards Maggie, fretted, "Up, up, wee, up."

Bessie, willing to save Maggie from interruption, took the small hand in her own, and began the oft-repeated tale; but neither did this answer. Baby, like many older people when they are sick,—aye, and when they are well too,—was not to be satisfied with anything but that on which she had, for the moment, set her fancy. Maggie's lap and Maggie's attention were the only things that could please her just then, and she could see no reason why she should not have them.

"Oh, you little bother! I shan't take you, and you can just let Bessie play with you, now!" said Maggie; "I am not going to stop my work just for such nonsense. Bessie can tell the pig that 'went to market' as well as I can; and she is not busy."

Baby might not understand the words, but she understood the tone, and knew very well that she was being scolded; and she put up a pitiful, grieved lip, which would have made Maggie feel sorry if she had seen it. But her eyes were bent upon her slate, not once turned towards little Annie.

Bessie looked from one sister to the other, and then said gently,—

"Maggie, dear, do you think you are doing the work our Father has given you to do now?"

Maggie coloured, and looked more vexed than she had done before, hesitated an instant, and then, as the cloud passed from her face, said,—

"No, Bessie, I am not; but I just will do it;" and in another moment baby was in the long-wished-for place, and that first little pig who went to market travelled there so many times that I think he would have been glad to be the brother who stayed at home.

Mamma came back just as nurse was through with Frankie, and said, as she took the now contented baby from Maggie, "You are my own dear, obliging little girl. I was sorry to interrupt you, but you see it could not be helped."

"But I was not obliging or kind at all, mamma," said Maggie; "at least, not at first. I felt real provoked 'cause I had to take care of baby, and I believe I would have let her cry if it hadn't been for Bessie, who put me in mind I was giving place to my own work, instead of God's. I s'pose it was God's work to amuse baby, even if it did not seem half so useful a thing as writing my composition—was it not, mamma?"

"Certainly, dear; and I am glad you saw that."

"Oh, it was not my praise at all, but Bessie's, mamma. She is an excellent reminder; and if I had not her, I expect I should be an awful child."

"I trust not, dear," said her mother, smiling.

"But, Maggie, dear," said Bessie, as her sister took up her slate once more, "I'm 'fraid you have something else to do. I think Marigold is hungry, and has no seed in his cup. You did not feed him this morning, did you?"

Maggie uttered an exclamation, and clapping her hand over her mouth, after the manner of little girls on such occasions, turned to meet her mother's half-mournful, half-reproachful look, and then ran away to her own room, followed by Bessie.

Poor little Marigold! It was easy to be seen that he was in a sad way about something, and a peep into his cage soon showed the cause. As the children came in, he was making a loud but mournful chirping, as if he wanted to call attention to himself; and, when he saw them, he commenced fluttering his wings and stretching out his neck towards them.

"Oh, you poor little birdie!" said Maggie; "did your naughty, ought-to-be-ashamed-of-herself Maggie forget all about you this morning? Yes, Bessie; his seed-cup is empty, and he has not had fresh water or anything. And it just came 'cause I was in such a hurry to get to my composition. Oh dear! I wonder if I am too anxious about it. You see, Bessie, it was this way. When Jane called me to feed him, I was just going to write, and I did not want to come at all, and thought I would wait; but then I remembered how mamma said, if she let me attend to him, I must promise to attend to him faithfully every morning; so I ran as quick as I could for the seed-box and a lump of sugar (for I saw yesterday his sugar was all gone), and I was in such a hurry that I let the box fall, and spilled all the seed, and it took me so long to pick it up; but all the time I was thinking about a very good idea I had, and now I remember I just went and put the box away, and forgot to give Marigold any seed. And there is the lump of sugar lying on the chair, and his water-cup is empty too. Poor little fellow! just see how hungry he is, Bessie! If his instinct tells him it was I who did it to him, I wonder if he'll forgive me and love me any more."

Marigold was certainly very hungry, but he did not seem to feel unforgiving, or to bear any grudge against his repentant little mistress; for, as he picked up seed after seed, and opened them with his sharp beak, he watched the children with his bright, black eyes as lovingly as usual, giving, every b and then, when he could spare the time, a cheerful chirp, which seemed to say, "Thank you; you have made amends for past neglect."

Maggie and Bessie stood and looked at him till he had made a good breakfast, and fallen to dressing his feathers, and then ran back to their mother's room, where the former told her how she had come so sadly to forget her duty that morning, a duty which she had, with many pleadings and promises, persuaded mamma to let her undertake, and which she had, till this unlucky day, never neglected.

"Mamma," she said, "do you think you will have to take away the charge of Marigold from me?"

"Not now, Maggie," said Mrs. Bradford. "You have been so faithful to him ever since you had him that I shall not punish you for this one failure. But it must not happen again, daughter; for, even if I thought it best to overlook such carelessness, it would be cruel and wrong for me to let the bird suffer through your fault."

"If I forget him again, mamma, I am sure I shall be very deserving of having you say Jane must take care of him; but I think this will keep me in mind. And I see quite well now how being so very anxious about my prize composition could make me careless about God's work. I have been in such a hurry with it this morning, because Gracie has a whole page of hers written, and I did not want her to be so much ahead of me. For, mamma, all the girls think now that one of us two will have the prize. None of the others think they have any chance; and I believe Miss Ashton thinks we are both too anxious about it, for yesterday Gracie was writing while we were at our arithmetic lesson, and Miss Ashton told her 'one thing at a time;' and, after school, she said that she was afraid some of the class were thinking too much about their compositions when they should be attending to other things; and I knew she meant Gracie and me, least I'm quite sure she meant me. And I would know it by to-day if I had not known it before," said Maggie, gravely shaking her head as she thought of her shortcomings of the morning. "Now, mamma, what plan do you think I could take to better myself of this?"

Mrs. Bradford could hardly help smiling at the air of grave importance with which this was said; but she saw that Maggie was quite in earnest, and meant what she said about correcting herself.

"I think, dear," she answered, "that the best way for you is to make sure each day that you have done everything else you have to do, before you take up your composition. When one duty is more pleasant than another, and one feels that one is apt to give too much place to it, it is better to put that last, and only to take it up when other work is done; and perhaps, as you have allowed the composition to tempt you into wrong more than once this morning, it would be well to put it away for to-day. I do not say you must do this; but do you not think it would help you to be more careful another time?"

"Yes'm," said Maggie, rather ruefully, and with a longing look at the slate; but presently she took it up, and went cheerfully to put it away.

"Mamma," said Bessie, "I think Maggie is pretty good about her composition, even if it does make her forget other things sometimes. She is not half so jealoused about it as I am. Sometimes when I think about Gracie having the prize, it makes me feel real mad and cross with her. I don't think she will have it; but then she might, you know; and I don't think I could bear that for Maggie."

"But you must try to be willing, dear," said her mother, "and not have that feeling towards Gracie. It does not make you act unkindly to her, does it?"

"It did the other day in school, mamma. She had lost her pencil, and she asked me to lend her mine; and 'cause I knew she wanted it for her composition, I spoke very cross, and told her 'No'; but then she looked so very surprised at me, that I was sorry and gave it to her, and we kissed and made up. But, mamma, if one of your little girls did not have a prize, would you not feel pretty mortified?"

"Not in the least, dear, if I thought my little girls had done as well as they could. If they had been idle or disobedient or untruthful, and so lost all chance of a prize, then indeed I should have been mortified and grieved; but, if they had done their best, I should not feel at all troubled because others had done better."

"And would not papa, mamma?"

"No; he will be quite satisfied if he knows that you have tried to do what is right."

"I'm 'fraid I shouldn't, mamma," said Bessie, drawing a long sigh; "if Gracie has the composition prize, not one will come to Maggie or me; and when I think about it I am quite dis-encouraged."

"But I do not want you to be discouraged, dearest, any more than I want you to be too eager. How is it that you have no hope of the other prizes for yourself or Maggie?"

"I could not have the 'perfect-lesson prize,' mamma, 'cause I do not have so many to say as the others; and Maggie has not had so many perfect marks as some of the rest."

"But that prize to be given by the choice of the school—has my Bessie given up all thought of that?" said Mrs. Bradford.

"Not the thought of it, mamma; but I have not a bit of hope of it. I think maybe Belle will have it; for she has been very good and sweet most all the time. She does not break the rules, and all the little girls and the young ladies like her. She says if it comes to her, she will give it to lame Jemmy, so that will be as good for him as if one of us had it; but I would have liked to think that Maggie or I had earned it for him."

"Yes," said Mrs. Bradford, "it would have been very pleasant; and I should have liked to think that the good behaviour and amiability of one of my little daughters had been of such service to Jemmy. But why do you think there is no hope that the prize will come to you, darling? You have not broken the rules so often, or had any trouble with your playmates, have you?"

"I don't think I have broken the rules, mamma; but I have been naughty sometimes. I broke Mrs. Ashton's flower, you know, and two or three times I was passionate with the girls; but I believe they don't think about that now, and some of them say they shall vote for me."

"Most all of them will," said Maggie, who had come back, and now stood listening; "most all of our class will, and I think a good many of the young ladies."

"No, not one," said Bessie, shaking her head decidedly.

"I don't see how you can be so sure," said Maggie; "and, Bessie, all the young ladies are very fond of you; and Miss Julia said you were the best child in the school."

"They have reasons, Maggie," said Bessie gravely; and then, turning to her mother, she added, "Mamma, don't you think it seems strange that God sometimes punishes us for doing right."

"I do not think He does, dear. God never punishes us for doing His will."

"No, mamma. I do not quite mean that. I s'pose punish was not just the right word; but I mean He lets a great disappointment come to us sometimes 'cause we try to do what we know is right. When I was very young, I used to think He always gave people a reward for doing right; but now I know better than that."

"Suppose you tell me your trouble, dear; and see if I cannot help you to understand it."

"Yes, mamma," said Bessie thoughtfully. "I think I might, for you know about the clock from Maggie, and so I shall not be breaking my promise."

And then she told her mother all about her trial and temptation in the affair of the broken clock.

Mrs. Bradford heard her in silence, only now and then tenderly smoothing her hair, or softly patting the little hand which rested on her knee; but Maggie went into a state of fidgety indignation, which she could scarcely restrain till the story was finished, when she broke out with,—

"I knew it! I knew it! I just knew it! That day that you were so mournful and mysterious, and wouldn't tell even me what ailed you, I knew those hateful old young ladies had been plaguing you some way; and I just hope not one of them will have a single prize! And I'm very much disappointed in Miss Kate. I didn't think she'd be so mean, even if she does tease."

Disappointed! So was Bessie, more sorely than could be put into words; and, in spite of Kate's continued, even increased kindness to her since that day, she could not get back the old feeling of trust and confidence. And Kate saw it, and grieved over it; and so, perhaps, the lesson she had received sank deeper into her heart.

"Bessie," said Mrs. Bradford, "is there not one reward of which we are always sure, if we do our Father's will?"

"Yes, mamma," said the little girl; "you mean, to know He is pleased with us. But it did seem as if He must be pleased, if I could be such a good child in school as to gain the prize that would be such a help to poor Jemmy; and it did seem as if it was very much His work, and I am very disappointed I could not do it."

"But sometimes, darling, we mean to serve God in one way, and He sees fit to have us do it in another; and sometimes we are doing His work and glorifying Him when we do not know it ourselves. Benito did not know he was carrying his pearls in his bosom, until he went into his Father's presence."

"No," said Bessie, smiling brightly at her mother's allusion to the old, well-loved story, and then looking grave again.

Mrs. Bradford saw that she was not quite content, and said,—

"Bessie, can you not feel satisfied to know that you have done more to serve and honour your Father in heaven by refusing to do evil that good might come, and holding firmly to the truth, than you would have done if you had gained fifty prizes for Jemmy?"

"Yes, mamma," said Bessie, brightening again; "and do you think God gave me that to be my work instead of earning the hospital bed?"

"I am sure of it, dear; and sure also that His blessing has followed your effort to keep in the way of truth."

"And, mamma, do you know I was thinking—I have to do a good deal of thinking about this—that even if I had promised to tell a story to Mrs. Ashton, and the young ladies had voted me the prize, it would not have been fair, 'cause it was for the best and most truthful child in the school; and they could not have given it to me for that, but 'cause I had done them a wicked favour."

"And you would have had no peace or contentment in gaining it so, darling, even if Jemmy had been cured by this means. And, Bessie, I am quite sure no one of your schoolmates cares less for you because you did not suffer them to tempt you into wrong, however vexed they might have been at the time."

"I care less for them," said Maggie, putting her arms around Bessie's neck; "and I'm just going to let them see it. I shan't speak to those four girls, or smile at them, but look very offended every time I see them. And I'm going to persuade all the rest of our class to be offended with them too."

"I do not want you to repeat this, Maggie," said Mrs. Bradford, to whom the story was not new, although the children thought it was.

"Mustn't I, mamma?" said Maggie, rather crestfallen. "Well, I suppose it would be telling tales; so I will just ask the other children to be offended with the big girls just to oblige me, and for a good reason that is a secret."

Mrs. Bradford did not make any reply to this. She did not wonder that Maggie was shocked and indignant; but she knew that her resentment was never lasting, and that long before Monday morning she would have thought better of this resolution. Nor was she wrong; for, having dismissed the children to be dressed before their little friends came, she overheard Maggie say,—

"Bessie, I guess after all I had better not coax our class to be offended with those larger girls; you see maybe they have begun to repent of their meanness, and it might discourage them if they would like to 'turn over a new leaf.' "

"Yes," said Bessie, "I think so too; and I meant to ask you not to, Maggie. Let's forgive and forget."

"I'll forgive, and I'll try to forget," said Maggie; "but I'm afraid that particular will be pretty hard work. But I will say that I hope perhaps one of them will have a prize after all, and I s'pose that will be a pretty good way of forgiving."

CHAPTER XII.

BESSIE'S PARTY.

"We are going to have a party," said Maggie.

"Who? our mamma?" said Nellie Ransom.

"Why, no," said Maggie: "we, Bessie and I. Next Tuesday is Bessie's birthday, when she will be seven years old; and mamma said we might have a party."

"Oh, how lovely!" said Dora Johnson; "and will you invite me, Maggie?"

"Well, yes, we will: 'cause mamma said we might have all the class," answered Maggie; "but, Dora, you ought not to ask us to invite you."

"Why not?" said Dora.

"Because it is not polite to ask people to invite you to their houses. We would have to, even if we did not want you, or else hurt your feelings by telling you we would rather not have you."

"You need not ask me if you don't want to," said Dora, pouting. "I don't care for going to your old party!"

"But we do want you, and you would like to come," said Bessie good-naturedly; "for it is going to be very nice, and we are to have a magic-lantern."

"Oh, how perfectly lovely!" said Fanny Leroy, clapping her hands. "I never saw a magic-lantern; I'll be sure to come."

"Now, there's another of you," said Maggie, in rather an aggrieved tone. "You ought not to say you'll come till you're invited. Bessie and I are going to send you an invitation all written in a note, and you must answer it in the same way, and not say you'll come before-time. I'm sorry I told you, if you act this way about it."

"When did you say it was to be?" asked Nellie.

"Next Tuesday," said Maggie: "the first of May. That's Bessie's birthday."

"And that is the day Miss Ashton's uncle is going to give the prizes," said Gracie Howard.

"Why, so it is!" said Lily Norris. "What a very 'markable day it will be for us!"

Here the bell rang, and the young voices were all hushed. But, after school was opened, the children found that one of the expected "remarkable" events would not, after all, take place on the first day of May.

"Children," said Miss Ashton, "a letter came from my uncle this morning, saying that he had been called out of town on very important business, and so could not be here on Tuesday to present the prizes. But on the following Thursday he hopes to be at home, and wishes to have all the compositions handed to him on the evening of that day, so that he may read them before Friday, when he will be here. We shall have no regular school on that day, but a little examination will take the place of the usual lessons; and you may tell such of your friends as would like to come that we will be happy to see them."

So the giving of the prizes was to be made quite a little affair. Some of the children were pleased, and some were not; timid Maggie, and one or two more who were afflicted with that troublesome shyness, being among the latter number.

But going to school had really proved of service to Maggie in conquering her extreme bashfulness, as her friends had hoped; and though her colour might still come and go, and her voice shake somewhat if a stranger spoke to her, she could now hold up her head, and answer as became a well-bred and polite little lady. Nor did she longer let it stand in the way of offering to do a kind thing for other people if she had the opportunity; but, when that came to her, tried to forget herself, and to think only of the help she might be. For, having the will to cure herself, Maggie had succeeded in her efforts, and her improvement in this respect was much to her credit.

As for Bessie, she cared little, except for Maggie's sake, whether there were half a dozen or fifty people present, besides those she called her "own." She was neither a shy nor a bold child; nor was she vain. But when she had a thing to do, she did it with a straightforward simplicity and a dignified, ladylike little manner, which were both amusing and attractive. If she knew the answer to a question, and that it was right for her to give it, she could do so almost as readily before a room full of people, as before one or two; and this was because she did not think of herself, or what people were thinking of her, but only if the thing were right, and of the proper way to do it.

Now I would by no means be understood to say that those little people who are not troubled with timidity themselves should blame or think hardly of those who suffer from it. It is a part of some natures, not of others; and those who are free from it should do all they can to help and encourage those who are not so. But certain it is that we can do much ourselves toward conquering this troublesome "little fox;" and, if my young readers could only know how much more happy as well as useful they may be when free from his vexatious attacks, I am sure they would do all they could to bury him out of sight and hearing.

For herself, Bessie had, as we know, no thought of a prize. From the older girls, influenced by Kate Maynard, she would not, she believed, receive a single vote. Kate had never withdrawn that threat; indeed, she had almost forgotten she had ever made it, and it never occurred to her that Bessie still expected her to act upon it. The little girls were divided, each one having her own favourite, whom she thought the most deserving, and for whom she intended to vote; and Bessie imagined that the only hope of the hospital bed for lame Jemmy lay with Belle Powers. For Belle was now so much interested in all that concerned Maggie and Bessie, that she was almost as anxious as they were to gain it for him; and she had been to Riverside with her young friends, and seen the lame boy, so that she took an interest in him on his own account also.

Lily Norris, too, had promised that if this prize came to her, she would give it to Jemmy; but there was small chance of that. Lily was a roguish, mischievous little thing, and a great chatterbox; and it would not do to tell how often she had broken the rules by talking and laughing aloud at forbidden times, throwing paper-balls, making faces, and so forth. No, no, Lily would never have the prize for being the best child in the school.

But in spite of her half-jealousy of Gracie Howard, and her acknowledgment to her mother that she might possibly earn the composition prize, Bessie had little doubt in her own mind that it would fall to Maggie, and thought it rather unreasonable in any one to expect to carry it away from her. Her own Maggie, who "made up" such delightful stories and plays, and who had written the "Complete Family," that wonderful book for which Uncle Ruthven had paid such a price, could scarcely fail to be the successful one here; and Bessie had little fear on that score. But she knew that Maggie's pleasure would be for the moment half destroyed if she were obliged to receive the prize in the presence of strangers; and she turned to her sister with a sympathising glance, which was met with a look of the utmost dismay from Maggie.

But there was one young heart there which was troubled with no such painful misgivings as poor Maggie's. A vain and ambitious little heart it was, and rather gloried in the opportunity of displaying its expected triumphs before a number of admiring eyes.

Gracie Howard was a very clever child, and none knew this better than herself. It had been often said in her hearing, not by her father and mother,—for they were too wise to do such a thing,—but by foolish people who imagined they would please her parents by saying so, and had no thought of the harm they might be doing the child. But Mr. and Mrs. Howard would have been far better satisfied to have their little daughter only half as clever, and to see her modest, humble, and free from the vanity which was spoiling all the finer traits of her character. Not that Gracie was a bad child by any means; on the contrary, she was, in many respects, a very sweet little girl. But ah, that ugly weed of self-conceit! how many fair plants and precious seeds it chokes up and keeps out of sight!

Mr. and Mrs. Howard had hoped that by sending her to school, where she would be thrown with other children, this fault of Gracie's might be checked. But it had only grown upon her, as they saw with sorrow.

Miss Ashton had a bright set of little girls in her class, but Gracie was certainly the brightest and quickest among them; and she very soon became aware of this. She had had more perfect lessons than any one of the others—that they all knew; and Gracie herself had not the least doubt that she would also have the best composition, and so gain both these prizes. She was not at all disturbed by the fact that all the other children, with whom gentle and modest Maggie was much more of a favourite than Gracie, declared their belief and hope that the former would be successful. She took it all good-naturedly, too well pleased with herself and her own performances to be vexed at anything they could say; and only answering, with a self-satisfied shake of the head, that they would "see who was the smartest when the day came."

She was really fond of Maggie Bradford, and felt sorry for the disappointment she thought was in store for her, and would have been glad if two composition prizes had been offered, so that her little companion might have one, provided that the first came to herself. Her father and mother would have been better pleased that she should have had none, and so learned that others could do as well and better than herself.

The class had a good deal to talk about that day, as soon as school was over. The arrangements for the prize-day and Bessie's party occasioned a good deal of chattering. They were all welcome to talk of the latter as much as they pleased, and to say how delightful it would be, and how much they expected to enjoy themselves; only, on no account was any one to say she was coming before she received her written invitation, and answered it in form. Maggie was very particular on that point.

The invitations were all sent and accepted in the most ceremonious manner, and quite to Maggie's satisfaction, on the following day, which was Saturday.

Even Belle Powers, who came to spend the day with Maggie and Bessie, received her note the moment she entered the house, and was requested to answer it before they began to play, which she did on a sheet of Bessie's stamped paper. To be sure, a slight difficulty arose from the fact that the initials, B. R. B. , did not stand well for Belle Powers; but that was speedily remedied by Maggie, who, with her usual readiness for overcoming such obstacles, suggested that they might for once be supposed to stand for "Beloved, Reasonable Belle;" an idea which met with the highest approbation from the other children. Nor was it of the slightest consequence that Maggie was herself obliged to dictate the words in which the invitation was to be accepted. It was enough that it was accepted; and, this important business being satisfactorily concluded, they all went happily to their play.

Tuesday afternoon came, bringing with it the merry, happy party to keep Bessie's birthday. Besides her young classmates, there were half a dozen other little ones; the family from Riverside and from grandmamma's; Mr. Hall and Mr. Powers; and last and least, but by no means the person of smallest importance, Mrs. Rush's bright, three-months-old baby, May Bessie, the "subject" of Maggie's famous composition, and our Bessie's particular pet and darling.

Bessie had a fancy—no one could tell how it had arisen—that the baby's pretty second name had been given for her. Perhaps if it had been necessary to undeceive her, young Mrs. Stanton might have laid claim to the honour; but, seeing the child's satisfaction in the idea, no one had the heart to do so. It gave her a special interest in the baby, and Mrs. Bradford and Colonel Rush were rather glad that it should be so, for they had feared that Bessie might think the colonel would care less for her, now that he had a little daughter of his own to pet and love.

But no shade of that slight feeling of jealousy with which Bessie had sometimes to do battle seemed to have been called forth by this new claimant on the hearts of her friends. Her delight in it was pure and unselfish; and it was for her and Maggie a fresh source of pleasure whenever they visited Colonel and Mrs. Rush.

And Maggie, partly to please Bessie, partly "for a compliment to Uncle Horace and Aunt May," had discarded all other subjects of composition, and taken this dear baby; telling how a little angel had wandered down from heaven to earth to see if it could be of any use there, and, falling in with "a brave, lame soldier" and his wife, concluded that it could not do better than stay and make them happy; "because they deserved to have a little bit of heaven in their home," wrote Maggie.

"A little bit of heaven" the baby had certainly brought with it, as the darlings usually do; and had Aunt May needed any further reward than she had already received for the loving teachings she had bestowed on her young Sunday scholars, she would have found it in the joy which they took in her joy, and in this pretty, simple story of Maggie's, which she laughed over and cried over, and then privately copied, putting the copy carefully away with some other small treasures which were very dear.

The birthday party could not be expected to go off well, unless that very considerate "little angel" took part in it; and so Aunt May had been coaxed to let her come for a short time. And certainly no young lady ever received a greater share of attention at her first party than did this little queen, who took it all in the most dignified manner, and as if it were a thing to which she was quite accustomed.

May Bessie had just been carried away by her nurse, when Gracie Howard came in, carrying in one hand a lovely bouquet, in the other a roll of paper neatly tied with a scarlet ribbon. The former she presented to Bessie; and the other children, supposing the latter to be some pretty picture, expected to see that placed in the same hands.

But that did not follow; and presently, when Maggie asked, "What would you all like to play first?" Gracie untied the ribbon, and said,—

"I've brought my prize composition, and I'll read it aloud. Don't you want to hear it?"

"No," said Dora Johnson and Mamie Stone; "we don't."

"Oh, but you must!" said Gracie, unrolling her paper and jumping upon a chair.

"Proudy! Proudy!" said Fanny Leroy; "you are always wanting to show off your own compositions."

"Before I'd think so much of myself!" cried another. But Gracie, nothing daunted, turned to Bessie and said,—

"You want to hear it, don't you, Bessie? and it's your party."

"No," said Bessie, her politeness struggling with her truthfulness and resentment at Gracie's vanity, "I don't want to hear it; but I'll let you read it, if you are so very anxious."

This was permission enough for Gracie; and she read aloud the composition with an air and tone which seemed to say, "There! do better than that if you can!"

Maggie and Bessie listened, feeling bound to do so, as Gracie was company; and, moreover, they both had a strong desire to judge for themselves if her composition was likely to prove the best. Two or three of the other little girls remained also from curiosity; but the most of them walked away in great disgust at Gracie's love of "showing off."

Several of the grown people were at the other end of the room, and Gracie raised her voice that they might also have the benefit of her performance; but, to her great mortification, not one of them seemed to pay the slightest attention. The truth was, they all heard well enough, but none of them chose to gratify the conceited little puss by letting her suppose they were listening.

Maggie's countenance fell as Gracie went on, but Bessie's brightened; and, at the close, she drew a long breath of satisfaction.

"There!" said Gracie triumphantly; "shan't I have the prize for that?"

"No," said Bessie, "I don't believe you will. It is very nice, Gracie, but my Maggie's is a great deal better—oh yes, a great deal better! It is beautiful! I'm sorry for you, if you're disappointed; but I know hers is the best, and I'm very glad for Maggie."

"You'd better not be so sure I'll be disappointed," said Gracie.

Bessie did not answer; but the very satisfied look with which she turned to her sister provoked Gracie.

"You think Maggie is so great!" she said.

"Yes, I do," answered Bessie defiantly.

"And I'd rather think my sister great than think myself great," said Nellie Ransom.

Here Mrs. Bradford, hearing that the young voices were not very good-natured in their tones, came to prevent a quarrel; and Annie Stanton, following, proposed a game of hide-and-seek. It was readily agreed to, and peace was restored.

The game went on for some time with great success, and at last it came to Bessie's turn to be hidden. Sending the seekers to their gathering place in the dining-room, Aunt Annie took her to the library, and hid her snugly away in a corner behind a tall pedestal, drawing the window-curtain about it so as to conceal her still further.

As Bessie lay there, listening to the voices of the other children as they wandered, now nearer, now farther off, in their search for her, her Uncle Ruthven and Colonel Rush came into the library, and placed themselves by the window near which she lay hidden.

"I'm here in the corner, Uncle Ruthven; but please don't take any notice, for fear the other children know," she whispered, but so softly that neither of the gentlemen heard her, and went on talking without knowing who was near them.

"That little Howard is an uncommonly clever child," said Mr. Stanton presently. "That composition is quite beyond her years."

"H'm!" said the colonel; "conceited little monkey!"

"Yes," said Mr. Stanton; "it is really painful to see an otherwise pleasant child so pert and forward."

"It is a great pity," said the colonel, "a great pity. I hope her self-conceit may not be encouraged by receiving the prize."

"I have no doubt that it will fall to her," said Uncle Ruthven. "You must acknowledge that, pretty as our Maggie's composition is, this of Gracie's goes before it in all those particulars which would be likely to take a prize."

"Yes," answered Colonel Rush reluctantly, "I suppose it does. I do not know that I should be an unprejudiced judge in this matter, owing to my special interest in Maggie's subject," he added, laughing; "and the simplicity and poetry of her little story have gone very close to my heart. But, apart from this, I do not think it will be well for Gracie to gain the prize; though I fear with you that she will be the successful candidate."

Bessie did not know what "candidate" meant; but she understood very well that her uncle and the colonel thought that Gracie would gain the prize; and who could be better judges than they?

She sat motionless with grief and amazement, forgetting her game, forgetting everything but Maggie's disappointment and her own. She did not hear anything more that was said by the two gentlemen; she did not notice when Uncle Ruthven opened the window, and they both stepped out upon the piazza; and when, a moment later, Lily Norris drew aside the curtain, and joyfully exclaimed, "Here she is!" Bessie felt almost angry that she was forced to come forth from her hiding-place.

She was not cross, however; she did not even let the tears find way; but her pleasure in her birthday party was quite gone. Not even that wonderful magic-lantern, which was displayed as soon as it was dark, to the great delight of the other children, could give her any satisfaction; and it was impossible to look at the troubled little face without seeing that something had happened greatly to disturb her.

But she could not be persuaded to say what ailed her, till all the young guests had gone, and mamma had taken her up-stairs, when she repeated, as nearly as she could, what her uncle and Colonel Bush had said.

Maggie, too, was dismayed at this sudden downfall of her hopes; for she agreed with Bessie that Uncle Ruthven and the colonel must know; and their mother, who had also heard Gracie's composition, could not encourage them by giving a contrary opinion.

"I must really say, dear Maggie," she said, "that I would rather have yours than Gracie's; but I think that hers is almost sure to be the successful one."

"And all Maggie's pains are lost," said Bessie mournfully.

"Not at all, dear. Maggie has done all she could be asked to do, her very best; and it is no fault of hers if another has in some respects done better. And her pains are by no means thrown away, if it were only for the pleasure her story has given to our dear Colonel and Mrs. Bush."

"Then I'm glad I took them," said Maggie; "but oh, mamma!" and she ended with a long sigh.

"So am I," said Bessie; "and I know the colonel thinks your composition is splendid, Maggie; and he would rather you should have the prize."

"I was afraid when I heard Gracie read hers," said Maggie. "It sounded so much more grown-up-y than mine. Mamma, did it make you feel sorry, too?"

"No, darling. I will tell you what I felt: that I would rather have my own Maggie as she is, even without the slightest hope of a prize, than to see her vain and forward, and winning the richest of earthly rewards."

CHAPTER XIII.

LOST AND FOUND.

The children were just ready to start for school the next morning, and papa had promised to walk as far as Mrs. Ashton's door with them, when there was a violent ringing at the hell; and, when the front door was opened, in rushed Gracie Howard, flushed and excited, and with her face wearing the marks of a hard fit of crying.

Her father followed her.

"Oh," exclaimed Gracie, without waiting to say "good-morning" herself, or allowing any one else to do so, "have you seen it? have you seen it?"

"Seen what?" asked Maggie and Bessie in a breath.

"There!" said Gracie, bursting into tears again; "I knew it! oh, I just knew it! I told you I was sure I brought it away with me, papa."

"What is the trouble?" asked Mr. Bradford, shaking hands with Mr. Howard.

"She has lost her composition," answered Mr. Howard. "It seems she brought it here yesterday afternoon, with the purpose, I am sorry to say, of making a display of it to her young companions; and this morning it was missing. She is quite positive she had it in her hands when she left your house, but does not recollect bringing it as far as our own; and her mother, who took off her cloak as soon as she came home, says she is quite sure Gracie carried no composition. But, although the child is so confident, I thought she might be mistaken, and find she had left it here. Good-morning, madam:" this to Mrs. Bradford, who had been called into the hall by Gracie's cries; and the difficulty was next explained to her.

"I believe Gracie is right," said the lady. "She left the paper lying on the library table, and, seeing it there just as she was going away, I brought it out and gave it to her. I do not think she can have left it here; but I will inquire if the servants have seen it."

The servants were questioned, but all declared they had seen nothing of the missing paper; and it seemed that Gracie must have lost it in the street. She moaned and sobbed and cried as if she had lost all the world held dear for her, and would not listen to a word of comfort. She thrust the children from her when they would have offered her their sympathy, saying she knew they were "glad, because now Maggie could have the prize;" nor would she listen to her father's entreaties and commands that she should be silent, although, at last, he spoke very severely to her, and was obliged to take her home, in spite of its being nearly school-time. She was in no state for school just then.

Maggie walked slowly by her father's side on the way to Mrs. Ashton's, not skipping and jumping as usual; and, when they reached the stoop, she seized hold of him, and said,—

"Papa, I'm afraid I feel glad about Gracie's composition. Do you think I am dreadfully awful?"

"No," said papa, smiling; "I do not. But if I were you, Maggie, I would not say 'awful' so much. That is something you have learned at school, which I should be glad to have you unlearn as soon as possible. But as to the composition—well, I suppose you could scarcely be expected to feel otherwise;" and Mr. Bradford smiled again as he thought that if he were questioned he might be obliged to confess to a share in Maggie's feelings. "I believe it is only natural, dear; but I hope you will not let Gracie see it."

"Oh no, papa!" said Maggie; "I hope I wouldn't be so mean as that. I do feel sorry for Gracie, even if I am glad for myself to have a better chance."

"And we'll try to be kinder to Gracie too, so she'll have no reason to think we're not sorry for her," said Bessie.

All this had made our little girls rather later than usual; and they had to take their places immediately, so that there was no opportunity to tell the news until school had been opened, when Miss Ashton, seeing Gracie was not present, turned to Maggie and said,—

"Gracie is absent. Did you make her sick at your party last night, Maggie?"

Then Maggie told of Gracie's loss; and two or three of the children said they remembered quite well that Mrs. Bradford had come into the hall, and handed Gracie her paper just before she went away.

The child came in a little later, looking the very picture of woe, and bringing an excuse for tardiness from her mother. But she was in no mood to meet any extra kindness in a grateful spirit; and showed herself altogether so pettish and disagreeable that Miss Ashton was more than once obliged to call her to order. Then she cried afresh, and said that every one was "hateful," and no one cared for her, and that she just believed they would not tell her if they knew where her composition was.

"Come here, Gracie," said Miss Ashton; and Gracie went slowly and reluctantly to her teacher's side. "Do you really think, if any of your schoolmates knew where your composition was, they would not tell you?" said the lady.

Gracie put up her shoulder, hung her head, and fidgeted from one foot to another; but Miss Ashton repeated her question.

Then, her ill-temper getting the upper hand of all her better feelings, she answered sulkily,—

"I don't believe Maggie or Bessie would. I know they are just glad enough."

"O-o-o-o-h! o-o-o-o-h! What a shame!" and such exclamations broke from the other children. But Miss Ashton commanded silence.

"That is a grave charge to bring against any one, Gracie, and especially against those who have been your friends for so long," said the lady. "I am ashamed of you."

And Gracie was ashamed of herself, though she would not acknowledge it; but only pouted the more at Miss Ashton's gentle reproof.

"Now, my dear," said the lady, "I cannot have you behaving in this way. You are interfering with the peace and comfort of the whole class; and, unless you can make up your mind to be reasonable, you must go and sit by yourself in the cloak-room."

Foolish Gracie! she chose the latter, and went away by herself to nurse her ill-humour and disappointed vanity.

There was no time now to write another composition. The rough sketch of the first she had thrown into the fire, thinking she would never need it again; and Gracie did not find her trouble easier to bear because it was, as her father had told her, the result of her own love of display.

Maggie and Bessie were both hurt and indignant at her injustice; but they knew she would be sorry for it when she was in a more reasonable humour, and would not agree to Belle's proposal that "the whole class should be mad with her as long as they lived."

Although Mrs. Bradford felt almost sure that Gracie had taken the missing paper away with her, and lost it on the way home, she had a thorough search made for it, but all in vain.

Harry and Fred, the latter especially, were openly jubilant over the loss, imagining, as every one else did, that this left a clear field for Maggie; and declared that "it served Miss Vanity right, and they were not a bit sorry for her."

That evening Mr. and Mrs. Bradford went out to dinner, leaving the children quietly amusing themselves in the library. Harry was reading aloud to his little sisters; while Fred was busy with some wax flowers, at which pretty work he was quite expert.

Flossy, not quite approving of such quiet doings, sat on the corner of Maggie's chair; but, had any one of the four been at leisure to notice him, they would have seen that he was watching his chance for any bit of mischief which might lead to a frolic.

Fred had spread a paper upon the table, so that the blue cloth with which it was covered might not become soiled with the wax and other materials with which he was busy. He was generally ready enough to indulge Flossy with a game of play; and the dog, finding that he could attract attention in no other way, suddenly jumped up, and seized the corner of the paper, dragging it half off the table, and upsetting a little saucer of pink powder with which Fred was colouring the rose he was making.

Fred was provoked, and sent him off with a cuff upon his ear, instead of the romp he had been looking for; then set about repairing the damage he had caused as speedily as possible, his brother and sisters coming to his help.

Some of the pink powder had gone upon the table, and, though Harry took it up carefully with a paper-knife, it left its traces behind.

"Oh, won't Patrick be in a taking when he sees the table?" said Fred.

"It will come off, I guess," said Harry. "Let's brush it up, so as not to vex his old soul. Bessie, run and bring the whisk brush out of the drawer in the hall table, that's a pet."

Away ran Bessie into the hall, and, going to the table, pulled open the drawer. As she did so, she heard something slip, with a little rustle like that of paper; but she did not pay much attention to it till she tried to shut the drawer, and found that there was something in the way which prevented it from closing tight.

Many children would have run away without waiting to see what was wrong, but that did not suit at all with Bessie's neat, orderly ways. Once more she pulled out the drawer, which moved stiffly as if it caught upon something, and peeped within. At first she could not see anything; and she drew it farther out. Again there came that rustle of paper; and, as she peered in, there, over the back of the drawer, half in, half out, was something white, with—Bessie could not see very distinctly, and she would not venture another glance—with something that looked as if it might be an end of scarlet ribbon hanging from it. She started, shut up the drawer hastily, thrusting it as far in as she could, and ran back to the library with her heart beating fast.

"Hallo!" said Fred, as he put out his hand to take the brush from her, "what has frightened you? You look as if you'd seen something."

"You have no right to say I saw anything," said Bessie, in a tone so sharp and angry that her brothers and sister looked at her in great surprise.

"Whew!" said Fred. "You seem to have picked up a fit of crossness any way. I'd like to know what has come over you so suddenly."

"You can just hush and let me alone," said Bessie, "I'll never bring you a brush again, Fred;" and then she ran out of the room, and up-stairs as fast as she could go.

"Well, did you ever?" exclaimed Fred.

"What can ail her?" said Harry. "She surely did not mind going for the brush?"

"Why, no," answered Fred; "she seemed ready enough; but she came back the next moment in such a fume, and looking scared out of her wits."

"I'm going to see," said Maggie: "she'll tell me;" and she ran after Bessie.

But Maggie was mistaken.

She found Bessie in their mother's room, her angry mood passing away; but she still looked flushed and troubled, and to all Maggie's anxious questioning she would give no satisfactory answer.

"You must have seen something that frightened you, didn't you, Bessie?"

"I don't know," answered Bessie: "I was frightened; but I don't know if I saw what I saw,—I mean I don't know if I saw what I thought I saw,—and I didn't want to look again."

"Was it a robber?" asked Maggie.

"No," said Bessie. "If it had been a robber, I'd have said, 'Thou shalt not steal,' and then run for Patrick to take him to the policeman."

"I guess he wouldn't have waited till Patrick came," said Maggie. "But tell me about it, Bessie."

"Not now, Maggie. Maybe I'll have to tell you some other time; but you wouldn't like to hear it, and I'll have to think about it first. Oh, I do wish mamma was home!"

"Is it a weight on your mind?" asked Maggie, who, as well as her sister, was very fond of this expression.

Bessie nodded assent with a long and solemn shake of her head.

"I think you might tell me," said Maggie.

"I don't mean to keep it secret from you for ever and ever," said Bessie; "but you see I'm not quite sure about something, and I'm 'fraid I ought to make myself sure. And if I was sure, I would not know what I ought to do. It is very hard to think what is right about it."

Maggie looked wonderingly into her sister's puzzled face. What could have happened to trouble her so in that moment or two she was out in the hall? But, anxious though she was, she asked no more questions, knowing that Bessie would tell her this wonderful secret when she was ready.

"There's the bell for our supper," she said. "Come down, and don't bother yourself any more about it."

Bessie obeyed the first injunction, but the second was out of her power. She was no longer cross, however, and begged Fred's pardon for having spoken so pettishly to him; but she sent away her supper almost untasted, and continued thoughtful and rather mournful till her bed-time. She was really glad when that hour came, and she was safe in bed, when she could think over this troublesome matter in quiet, and ask for the help which never failed her.

She thought she should stay awake till her mother came home; and, as she lay tossing and restless, it seemed to her that mamma was staying away half the night. But, although it was not really so very late, she had dropped off to sleep before her mother came to see if her little girls were all safe and quiet for the night; and mamma was sorry to find Bessie's face and pillow wet with tears.

Nurse could not tell what the trouble had been, only that Bessie had seemed dull and out of spirits when she put her to bed, and would not say what ailed her.

The little girl woke very early the next morning, and, finding Maggie still sleeping, she lay quietly thinking.

Thinking of that which had troubled and puzzled her so last night; but now it seemed all clear.

She feared that the paper which she had seen in the drawer was Gracie's composition; but she was not sure; and she had had a hard struggle with herself, trying to believe that it was not her duty to go and find out.