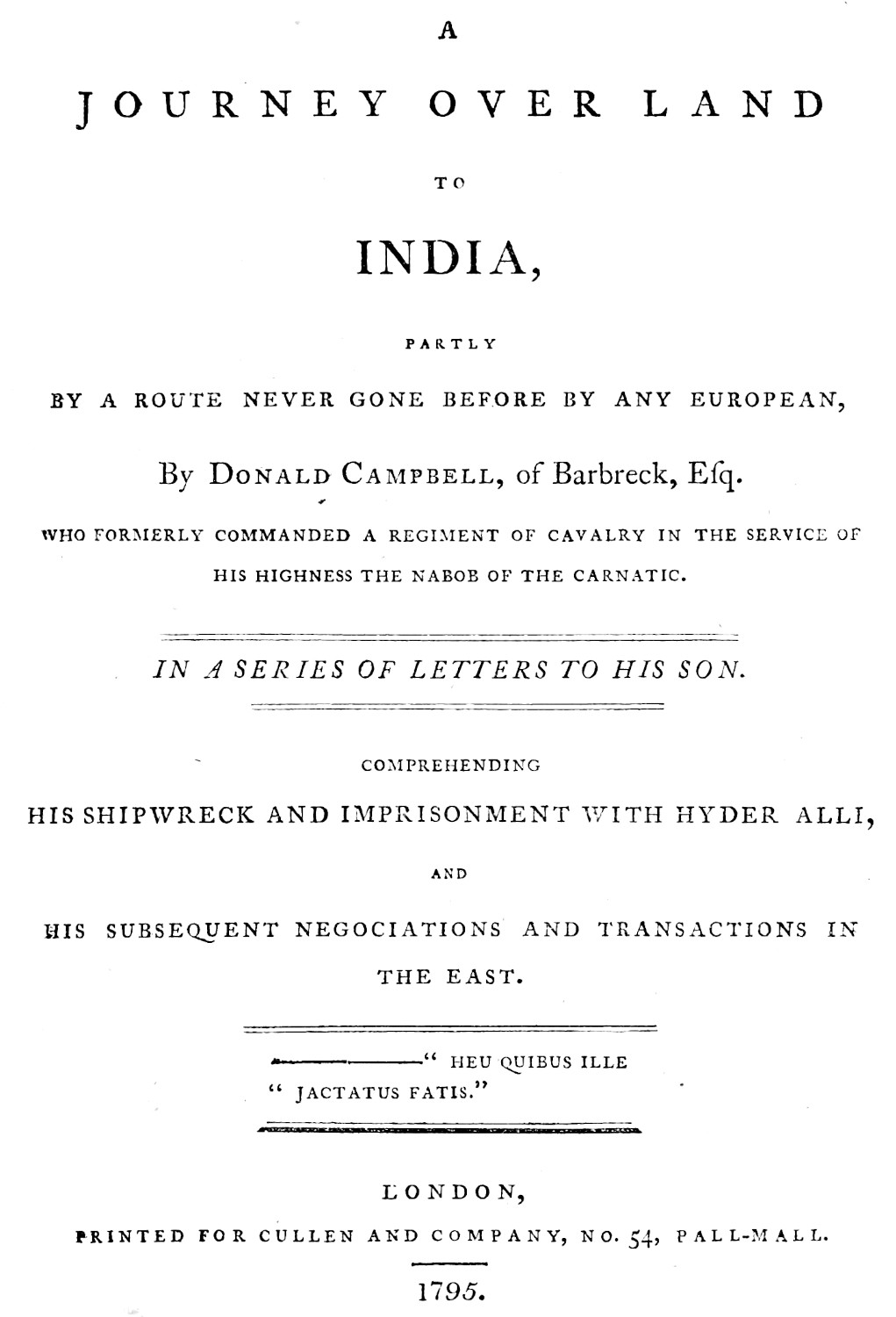

A journey over land to India

Play Sample

ADVERTISEMENT.

The Events related in the following Pages, naturally became a frequent subject of conversation with my Children and my Friends.They felt so much satisfaction at the accounts which I gave them, that they repeatedly urged me to commit the whole to paper; and their affectionate partiality induced them to suppose, that the Narrative would be, not only agreeable to them, but interesting to the Public.In complying with their solicitations, I am far from being confident that the success of my efforts will justify their hopes: I trust, however, that too much will not be expected, in regard to literary composition, from a person whose life has been principally devoted to the duties of a Soldier and the service of his Country——and that a scrupulous adherence to Truth will compensate for many blemishes in style and arrangement.

Author’s Motives for going to India. Melancholy Presentiments. Caution against Superstition. Journey to Margate. Packet. Consoled by meeting General Lockhart on board. Lands at Ostend.

Short Account of the Netherlands. Conduct of the Belgians. Ostend described. Wonderful Effects of Liberty on the Human Mind, exemplified in the Defence of Ostend against the Spaniards.

Caution against using Houses of Entertainment on the Continent kept by Englishmen. Description of the Barques. Arrives at Bruges. Gross Act of Despotism in the Emperor. Imprisonment of La Fayette

Description of Bruges.Reflections on the Rise and Decay of Empires.Chief Grandeur of the Cities of Christendom, consisted in Buildings, the Works of Monkish Imposture and Sensuality.Superstition a powerful Engine.

Opulence of the Bishop of Bruges; Cathedral. Church of Notre Dame. Vestments of Thomas a BecketExtraordinary Picture.Monastery of the Dunes.The Mortification of that Order.A curious Relic.

Passage to Ghent. Cheapness of Travelling. Description of Ghent Cathedral. Monastery of St. Pierre. Charity of the Clergy.

Description of two brazen Images, erected in Commemoration of an extraordinary Act of Filial Virtue.Journey from Ghent through Alost to Brussels.

Short Description of Brussels.Royal Library.Arsenal.Armour of Montezuma.The Enormities committed under the Pretext of Christianity, by far greater than those committed by the French in the Frenzy of Emancipation.

Brussels continued.Churches, Chapels, Toys, Images and Pictures.A Host, or Wafer, which was stabbed by a Jew, and bled profusely.Inns excellent and cheap.

General Remarks on the People of the Netherlands. Account of the Emperor Joseph the Second. Anecdote of that Monarch. His Inauguration at Brussels. Burning of the Town-House. Contrasted Conduct of the Belgians to Joseph on his Arrival, and after his Departure. The detestable Effects of Aristocracy.

Liege. Constitution of the German Empire. Tolerant Disposition of Joseph the Second, occasions a Visit from His Holiness the Pope, who returns to Rome in Disappointment. Situation of the present Emperor. Reflections on the Conduct of Russia and Prussia to Poland.

Luxury of the Bishop of Liege. Reflections on the Inconsistency of the Professions and Practice of Churchmen, particularly the Nolo Episcopari, which Bishops swear at their Instalment. Advantages of the Study of the Law in all Countries. Liege, the Paradise of Priests. Sir John Mandeville’s Tomb.

Aix-la-Chapelle.A bit of Earth in a Golden Casket.Consecration of the Cathedral, by an Emperor, a Pope, and three hundred and sixty-five Bishops.Their valuable Presents to that Church.

Juliers.Reflections on Religious Persecution.Cologne.Church of St.Ursula.Bones of eleven thousand Virgin Martyrs.Church of St.Gerion.Nine hundred Heads of Moorish Cavaliers.Reflections on the Establishment of Clergy, and the Superiority of that of Scotland.

Cologne continued. Strange Ambition of Families to be thought Descendants of the Romans. Story of Lord Anson and a Greek Pilot. Bonne. Bridge of Cæsar. Coblentz. Mentz. Frankfort.

Frankfort described.Golden Bull.Augsburgh.Manufactory of Watch-Chains, &c.Happy State of Society arising from the tolerant Disposition of the Inhabitants.

Tyrolese.Innspruck.Riches of the Franciscan Church there.One Mass in it sufficient to deliver a Soul from Purgatory.Hall.Curiosities at the Royal Palace of Ombras.Brisen.Valley of Bolsano.Trent.

Description of the Bishopric of Trent.Obvious Difference between Germany and Italy.Contrast between the Characters of the Germans and Italians.Council of Trent.Tower for drowning Adulterers.Bassano.Venice.

Concubinage more systematically countenanced in Venice than London.Trieste.Loss of Servant and Interpreter.Sail for Alexandria.Zante.

Adventure at the Island of Zante.Alexandria.The Plague, and an Incursion of the Arabs.Pompey’s Pillar, Cleopatra’s Obelisk, &c.Island of Cyprus.Latichea.Aleppo.

Aleppo continued.Puppet-shews.Raraghuze, or Punch, his Freedom of Speech and Satire.

Description of Tartar Guide.His Conduct.Arrival at Diarbeker.Padan Aram of Moses.Scripture Ground.Reflections.Description of the City of Diarbeker.Whimsical Incident occasioned by Laughing.Oddity of the Tartar.

Strange Traits in the Tartar’s Character.Buys Women, ties them up in Sacks, and carries them 50 Miles.Reflections on the Slave Trade.Apostrophe to the Champion of the oppressed Africans.

Extravagant Conduct of the Tartar, which he afterwards explains satisfactorily.Extraordinary Incident and Address of the Tartar, in the Case of Santons.

Arrives at Mosul.Description thereof.A Story-teller.A Puppet-shew.The Tartar forced to yield to Laughter, which he so much condemned.Set out for Bagdad.Callenders—their artful Practices.

Arrives at Bagdad.Whimsical Conduct of the Guide.Character of the Turks.Short Account of Bagdad.Effects of Opinion.Ruins of Babylon.Leaves Bagdad.Attacked by Robbers on the Tigris.

Arrives at Bassora.Account of that City.Leaves it, and arrives at Busheer.More Disappointments.Bombay.Goa.Gloomy Presentiments on leaving Goa.A Storm.

History of Hyat Sahib. Called upon to enter into the Service of Hyder, and offered a Command. Peremptorily refuses. Another Prisoner, a Native. Court of Justice. Tortures and Exactions. Mr. Hall declining fast.

Pressed to enter into the Service of Hyder AlliRefusal.Threatened to be hanged.Actually suspended, but let down again.Still persists in a Refusal, and determined to undergo any Death rather than enter.Projects a Plan to excite a Revolt, and escape.

Account of Hyder, and Indian Politics continued. General Mathews’s Descent on the Malabar Coast.Mounts the Ghauts.Approaches towards Hydernagur.Author’s Delight at getting into the open Air.Delivered by an unexpected Encounter from his Guards.

Meeting with General Mathews. Returns to the Fort with a Cowl. Delivers it to the Jemadar. Leads General Mathews into the Fort, and brings him into the Presence of the Jemadar. English Flag hoisted. Vindication of General Mathews from the Charge of Peculation.

Sets off for Bengal. Cundapore. Unable to proceed. Letter from General Mathews. Proceeds in an open Boat for Anjengo. Stopped by Sickness at Mangalore. Tellicherry. Anjengo. Travancore. Dancing Girls. Palamcotah. Madura. Revolt of Isif Cawn

Passage to Bengal. Negociation for Hyat Sahib. Mr. Hastings. Sir John Macpherson. Hear from Macauley, Sir John’s Secretary, of the Servant I lost at Trieste.Jagranaut Pagoda.Vizagapatnam.

Masulipatam. Arrives at Madras. Determines to proceed on Hyat’s Business to Bombay.Reaches Palamcotah.Takes sick.Recovering, crawls to Anjengo, and thence to Bombay.Resolves to return again to Madras.Adventure with a young Lady.Surat.China.Bath.Conclusion.

ERRATA.

| PART I. | |

| P.L. | |

| 9.2. | For shroud, read shrewd |

| 24.2. | For le berque, read la barque |

| 30.3. | For conquerous, read conquerors |

| 40.1. | For berque, read barque |

| 41.15. | For berque, read barque |

| 138.18. | For I, read It |

| 147.14. | For prospect, read appearance |

| 156.18. | For Sucz, read Suez |

| 162.15. | For reget, read regret |

| 165.15. | For exporium, read emporium |

| PART II. | |

| P.L. | |

| 16.18. | For snow, read storm |

| 16.7. | For ports, read parts |

| 21.10. | For rolling, read bailing |

| 24.4. | After to, insert be |

| 30.2. | For I, read It |

| 71.17. | For conscience, read convenience |

| 90.3. | For or, read for |

| 108.24. | For one, read ten |

| 122.1. | For shewed, read shewn |

| 129 19. | For Troop, read Company |

LETTER I.

My dear Frederick,

The tenderness of a fond father’s heart admonishes me, that I should but poorly requite the affectionate solicitude you have so often expressed, to become acquainted with the particulars of my journey over land to India, if I any longer withheld from you an account of that singular and eventful period of my life. I confess to you, my dear boy, that often when I have endeavoured to amuse you with the leading incidents and extraordinary vicissitudes of fortune which chequered the whole of that series of adventures, and observed the eager attention with which, young though you were, you listened to the recital, the tender sensibility you disclosed at some passages, and the earnest desire you expressed that “I should the whole relate,” I have felt an almost irresistible impulse to indulge you with an accurate and faithful narrative, and have more than once sat down at my bureau for the purpose: but sober and deliberate reflection suggested that it was too soon, and that, by complying with your desire at such a very early period of your life, I should but render the great end that I proposed by it abortive, frustrate the instruction which I meant to convey, and impress the mere incident on your memory, while the moral deducible from it must necessarily evaporate, and leave no trace, or rather excite no idea, in a mind not sufficiently matured for the conception of abstract principles, or prepared by practice for the deduction of moral inferences.

I am aware that there are many people, who, contemplating only the number of your days, would consider my undertaking this arduous task, and offering it to your reflection, even now, premature: but this is a subject on which I have so long and so deliberately dwelt, which I have discussed with so much care, and examined with such impartiality, that I think I may be acquitted of vanity, though I say I am competent to form a judgment on it. The result of that judgment is, that I am determined to indulge you without further delay; and I trust that you will not, on your part, render it an empty indulgence, but, on the contrary, by turning every circumstance to its best use, by converting every feeling which these pages may excite in your heart into matter of serious reflection, and by making every event (as it happens to deserve) an example to promote either emulation on the one hand, or circumspection and caution on the other, justify me in that opinion of you on which I found this determination.

I remember, that when, at an early age, I entered upon that stage of classical education at which you are now, at an earlier age, arrived——I mean, the Æneid——I was not only captivated with the beautiful story of the Hero, in the second Book, but drew certain inferences from parts of it, which I shall never forget, and which afterwards served to give a direction to the growth of my sentiments on occasions of a similar nature: above all, the filial piety of Æneas made a deep impression on my mind, and, by imperceptibly exciting an emulation in my bosom, augmented considerably the natural warmth of my affection and respect for my father. It is under the recollection of this sensation, and a firm persuasion that your heart is fully as susceptible of every tender impression, and your understanding as fit for the reception of useful history, as mine was then, that I overlook your extreme youth, and write to you as though you were an adult. If there be a thing on earth of which I can boast a perfect knowledge, it is my Frederick’s heart: it has been the object of my uninterrupted study almost since it was first capable of manifesting a sensation; and, if I am not very much mistaken in it indeed, the lively interest he feels in the occurrences of his father’s life, is the result, not of idle curiosity, but unbounded filial affection. Such an amiable motive shall not be disappointed in its end; and while I discharge the duty of a parent in gratifying it, I shall be encouraged and sustained under my labours by the sanguine expectation, that he will derive from my exertions the most solid advantages in his future progress through life. As those advantages are expected also to extend to my dear boy John, whose tender years disqualify him from making the same immediate reflections on the various subjects as they occur, my Frederick will perceive that it becomes his duty, not only as a good son, but as an affectionate brother, to assist and enforce them upon his mind, to explain to him the difficulties, and furnish him with his reasonings and inferences on them, so as that they may make, as nearly as possible, equal impressions on the heart and understanding of both.

And though few have the felicity to be warned by other men’s misfortunes or faults, because they seldom make deep impressions on their feelings, I am convinced that my sufferings and errors, as they will interest my Frederick’s heart, and gratify his curiosity, cannot fail to enlarge his understanding, and improve his conduct.

LETTER II.

Having, in compliance with your reiterated solicitations, determined to give you a narrative of my journey to the East Indies, and the singular turns of fortune which befel me there, I think it necessary, on reflection, to prepare you still further for the reception of it, by proposing certain terms to be fulfilled on your part; and as, in my last, I told you that I expected you, and, with your assistance, your brother, to turn my relation to a more useful account than the gratification of mere idle curiosity, by letting the moral deducible from my errors and misfortunes strike deep and take root in your mind——so there are other things, which, though not so extremely important, are too weighty to be neglected; to which I desire to direct your attention.

I believe you must have already perceived, that the wellbeing of yourself and your brother is my first——I might, perhaps, without trespassing much upon truth, say, my only object in life; that, to the care of your education, and the cultivation of your mind, I exclusively devote my time and my thoughts; and that, to insure your future happiness, I would sacrifice every thing I have a right to dispose of, and risk even life itself.The time, I trust, is not far distant, when your brother will be as well qualified to understand this as you are now——when both will feel alike the important duty it enforces on you——and when your only emulation will be, who shall produce the most luxuriant harvest to reward the labours I have taken——to reward yourselves.

In order, therefore, on my part, to give every thing I do a tendency to the great object of my wishes, and induce you, on your’s, to contribute your share to it, I shall give you, as I proceed in my narrative, a topographical description of the various Countries through which I shall have occasion to conduct you, and, as concisely as may be, an account of their manners, policy, and municipal institutions, so far as I have been able to collect them; which I hope will serve to awaken in you a thirst for those indispensable parts of polite education, Geography and History. I expect that you will carefully attend to those sciences, and that you will not suffer yourself, as you read my Letters, to be carried away by the rapid stream of idle curiosity from incident to incident, without time or disposition for reflection: you must take excursions, as you go along, from my Letters to your Geographical Grammar and your Maps——and, when necessary, call in the aid of your Tutor, in order to compare my observations with those of others on the same places, and by those means to acquire as determinate an idea as possible of their local situation, laws, and comparative advantages, whether of Nature or Art. You will thus enable yourself hereafter to consider how Society is influenced, and why some Communities are better directed than others.

Here I must observe to you, that as Geography is a science to which rational conversation, as supported by Gentlemen of breeding and education, most frequently refers, the least ignorance of it is continually liable to detection, and, when detected, subjects a man to the most mortifying ridicule and contempt.

The ingenious George Alexander Steevens has, in his celebrated Lecture upon Heads, given a most ludicrous instance of this species of ignorance, in the character of a Citizen, who, censuring the incapacity of Ministers, proposes to carry on the War on a new plan of his own. The plan is, to put the Troops in cork jackets——send them, thus equipped, to sea——and land them in the Mediterranean: When his companion asks him where that place lies, he calls him fool, and informs him that the Mediterranean is the Capital of Constantinople.Thus, my dear son, has this satirist ridiculed ignorance in pretenders to education; and thus will every one be ridiculous who betrays a deficiency in this very indispensable ingredient in forming the character of a Gentleman.But a story which I heard from a person of strict veracity, will serve more strongly to shew you the shame attendant on ignorance of those things which, from our rank, we are supposed to know; and as the fear of shame never fails to operate powerfully on a generous mind, I am sure it will serve to alarm you into industry, and application to your studies.

During the late American War, about that period when the King of France was, so fatally for himself, though perhaps in the end it may prove fortunate for the interests of Mankind, manifesting an intention to interfere and join the Americans, a worthy Alderman in Dublin, reading the newspaper, observed a paragraph, intimating, that in consequence of British cruisers having stopped some French vessels at sea, and searched them, France had taken umbrage! The sagacious Alderman, more patriotic than learned, took the alarm, and proceeded, with the paper in his hand, directly to a brother of the Board, and, with unfeigned sorrow, deplored the loss his Country had sustained, in having a place of such consequence as Umbrage ravished from it! ——desiring, of all things, to be informed in what part of the world Umbrage lay. To this the other, after a torrent of invective against Ministers, and condolence with his afflicted friend, answered that he was utterly unable to tell him, but that he had often heard it mentioned, and of course conceived it to be a place of great importance; at the same time proposing that they should go to a neighbouring Bookseller, who, as he dealt in Books, must necessarily know every thing, in order to have this gordian knot untied. They accordingly went; and having propounded the question, “what part of the globe Umbrage lay in?” the Bookseller took a Gazetteer, and, having searched it diligently, declared that he could not find it, and said he was almost sure there was no such place in existence. To this the two Aldermen, with a contemptuous sneer, answered by triumphantly reading the paragraph out of the newspaper. The Bookseller, who was a shrewdshrewd fellow, and, like most of his Countrymen, delighted in a jest, gravely replied, that the Gazetteer being an old edition, he could not answer for it, but that he supposed Umbrage lay somewhere on the coast of America. With this the wise Magistrates returned home, partly satisfied: but what words can express their chagrin when they found their error——that the unlucky Bookseller had spread the story over the City——that the newspapers were filled with satirical squibs upon it——nay, that a caracature print of themselves leading the City-watch to the retaking of Umbrage, was stuck up in every shop——and finally, that they could scarcely (albeit Aldermen) walk the streets, without having the populace sneer at them about the taking of Umbrage!

Thus, my child, will every one be more or less ridiculous who appears obviously ignorant of those things which, from the rank he holds in life, he should be expected to know, or to the knowledge of which vanity or petulance may tempt him to pretend.

I am sure I need not say more to you on this subject; for I think you love me too well to disappoint me in the first wish of my heart, and I believe you have too much manly pride to suffer so degrading a defect as indolence to expose you hereafter to animadversion or contempt. Remember, that as nothing in this life, however trivial or worthless, is to be procured without labour——so, above all others, the weighty and invaluable treasures of erudition are only to be acquired by exertions vigorously made and unremittingly continued.

“Quid munus Reipublicæ majus aut melius afferre possumus quam si juventutem bene erudiamus.”——Thus said the matchless TullyIf, then, the education of youth interests so very deeply a State, can it less powerfully interest him who stands in the two-fold connection of a Citizen and Parent?It is the lively anxiety of my mind, on this point, that obliges me to procrastinate the commencement of my narrative to another Letter, and induces me to entreat that you will, in the mean time, give this the consideration it deserves, and prepare your mind to follow its instructions.

LETTER III.

A variety of unpropitious circumstances gave rise to my journey to the East Indies, while domestic calamity marked my departure, and, at the very outset, gave me a foretaste of those miseries which Fate had reserved to let fall upon me in the sequel. The channels from which I drew the means of supporting my family in that style which their rank and connections obliged them to maintain, were clogged by a coincidence of events as unlucky as unexpected: the War in India had interrupted the regular remittance of my property from thence: a severe shock which unbounded generosity and beneficence had given to the affairs of my father, rendered him incapable of maintaining his usual punctuality in the payment of the income he had assigned me; and, to crown the whole, I had been deprived, by death, of two lovely children (your brother and sister), whom I loved not less than I have since loved you and your brother.

It was under the pressure of those accumulated afflictions, aggravated by the goading thought of leaving my family for such a length of time as must necessarily elapse before I could again see them, that I set out for India in the month of May, in the year 1781, with a heart overwhelmed with woe, and too surely predictive of misfortunes.

From the gloomy cave of depression in which my mind was sunk, I looked forward, to seek, in the future, a gleam of comfort——but in vain: not a ray appeared——Melancholy had thrown her sombre shadow on the whole.Even present affliction yielded up a share of my heart to an unaccountable dismal presentiment of future ill; and the disasters and disappointments I had passed, were lost and forgotten in ominous forebodings and instinctive presages of those that were to come.

Of all the weaknesses to which the human mind is subject, superstition is that against which I would have you guard with the utmost vigilance. It is the most incurable canker of the mind. Under its unrelenting dominion, happiness withers, the understanding becomes obscured, and every principle of joy is blasted. For this reason I wish to account for those presages, by referring them to their true physical causes, in order thereby to prevent your young mind from receiving, from what I have written, any injurious impression, or superstitious idea of presentiment, as it is fashionably denominated.

If the mind of Man be examined, it will be found naturally prone to the contemplation of the future——its flights from hope to hope, or fear to fear, leading it insensibly from objects present and in possession, to those remote and in expectation——from positive good to suppositious better, or from actual melancholy to imaginary misfortune. In these cases, the mind never fails to see the prospect in colours derived from the medium through which it is viewed and exaggerated by the magnifying power of fancy. Thus my mind, labouring under all the uneasiness I have described, saw every thing through the gloomy medium of melancholy, and, looking forward, foreboded nothing but misfortune: accident afterwards fulfilled those forebodings; but accident, nay, the most trifling change of circumstances, might possibly have so totally changed the face of my subsequent progress, that good fortune, instead of misadventure, might have been my lot, and so all my foreboding been as illusory and fallible as all such phantoms of the imagination really are. Thus I argue now——and I am sure I argue truly; but if reason be not timely called in, and made, as it were, an habitual inmate, it avails but little against the overbearing force of superstition, who, when she once gets possession of the mind, holds her seat with unrelenting tenacity, and, calling in a whole host of horrors, with despair at their head, to her aid, entrenches herself behind their formidable powers, and bids defiance to the assaults of reason.

Thus it fared with me——Under the dominion of gloomy presentiment, I left London; and my journey down to Margate, where I was to take shipping, was, as Shakspeare emphatically says, “a phantasm, or a hideous dream——and my little state of Man suffered, as it were, the nature of an insurrection:”——the chaos within me forbade even the approach of discriminate reflection; and I found myself on board the Packet, bound to Ostend, without having a single trace left upon my mind, of the intermediate stages and incidents, that happened since I had left London.

It has been observed——and I wish you always to carry it in memory, as one of the best consolations under affliction——that human sufferings, like all other things, find their vital principle exhausted, and their extinction accelerated, by overgrowth; and that, at the moment when Man thinks himself most miserable, a benignant Providence is preparing relief, in some form or other, for him. So it, in some sort, happened with me; for I was fortunate enough to find in the Packet a fellow-passenger, whose valuable conversation and agreeable manners beguiled me insensibly of the gloomy contemplation in which I was absorbed, and afforded my tortured mind a temporary suspension of pain. This Gentleman was General Lockhart: he was going to Brussels, to pay his court to the Emperor Joseph the Second, who was then shortly expected in the Low Countries, in order to go through the ceremonies of his Inauguration. As Brussels lay in my way, I was flattered with the hopes of having for a companion a Gentleman at once so pleasing in his manners and respectable in his character, and was much comforted when I found him as much disposed as myself to an agreement to travel the whole of the way thither together. Thus, though far, very far from a state of ease, I was, when landing at Ostend, at least less miserable than at my coming on board the Packet.

As this Letter is already spun to a length too great to admit of any material part of the description I am now to give you of Ostend, and the Country to which it belongs, I think it better to postpone it to my next, which I mean to devote entirely to that subject, and thereby avoid the confusion that arises from mixing two subjects in the same Letter, or breaking off the thread of one in order to make way for the other.

Adieu, my dear boy! ——Forget not your brother JohnThat you may both be good and happy, is all the wish now left to, &c.

LETTER IV.

That Country to which I am now to call your attention——I mean, the Netherlands——is marked by a greater number of political changes, and harrassed by a more continued train of military operations, than perhaps any Country in the records of Modern History.It may truly be called the Cockpit Royal of Europe, on which Tyrants, as ambition, avarice, pride, caprice, or malignity, prompted them, pitted thousands, and hundreds of thousands, of their fellow-creatures, to cut each other’s throats about some point, frivolous as regarding themselves, unimportant to Mankind, and only tending to gratify a diabolical lust for dominion: Yet, under all these disadvantages, (such are the natural qualities of this Country), it has, till lately, been in a tolerably flourishing state; and would, under good government and proper protection, equal any part of Europe for richness.

Flanders, Brabant, and the Country now called the United Netherlands, were in general known by the name of Netherlands, Low Countries, or Païs-bas, from their situation, as it is supposed, in respect of Germany. Anciently, they formed a part of Belgic Gaul, of which you may remember to have read an account in the Commentaries of Julius Cæsar, who describes the inhabitants as the most valiant of all the Gallic Nations——“Horum omnium Belgæ sunt fortissimi.” They afterwards were subject to petty Princes, and made part of the German Empire; and, in the sixteenth century, became subject to Charles the Fifth of the House of Austria; but, being oppressed beyond endurance by his son, Philip the Second of Spain, (that blind and furious bigot), they openly revolted——flew to arms to assert their freedom; and, after a struggle as glorious in effect as virtuous in principle——after performing prodigies of valour, and exhibiting examples of fortitude, to which none but men fighting in the Godlike Cause of Liberty are competent——led on by the wisdom and valour of the Prince of Orange, and assisted by the Sovereign of Great Britain——they at length so far succeeded, that those now called the United Netherlands, entered into a solemn league, and forced the gloomy Tyrant to acknowledge their independence. But that part to which I am now particularly to allude, continued annexed to the House of Austria. In 1787, they revolted, and made a temporary struggle to disengage themselves from the dominion of the Emperor; but, owing to some cabals among themselves, and the temperate conduct of that Prince, they again returned to their allegiance, and were rewarded with a general amnesty. In 1792, they were over-run by the French Army under General Dumourier——opened their arms to those Republicans, and were rewarded for it by oppression, tyranny, and injustice. The French, however, were driven back out of the Country; and, wonderful to relate, they again received their old Master, the Emperor, with strong demonstrations of joy, and manifested their loyalty and attachment to him by every expression that abject hypocrisy could suggest.

Here, could I stop with strict justice, I would——But, behold!the French again came; again they opened their gates to receive them; and again they were, with tenfold fury and rapacity, pillaged, oppressed, and insulted; and at the very time I am writing this, the Guillotine is doing its office——enforcing the payment of the most exorbitant and enormous contributions, and compelling, it is said, one hundred thousand of the ill-fated inhabitants to take the field, as soldiers of the Republic.

Human opinion is so chequered and uncertain, that two very honest men may in certain cases act in direct contradiction and hostility to each other, with the very best intentions——He, therefore, must have but a cold heart, and a contracted understanding, who cannot forgive the man that acts in such cases erroneously, when he acts from the exact dictates of his opinion, and upon the principle which he has conscientiously adopted: but when a whole People are seen whisking about with every gust of fortune, and making a new principle for every new point of convenience, we must despise them even when they happen to act right, and can scarcely afford them so much as pity in their calamities.The Austrian Netherlands are now in that state; and, without presuming to say in which of their tergiversations they were right, I will venture to pronounce that they deserve punishment, and I believe they are in hands very likely to give them their due.

To return——Ostend is a sea-port of Austrian Flanders, and is situated in the Liberty of Bruges. It was, at one time, the strongest town in Flanders: but a double ditch and ramparts, which constituted its strength, are now destroyed; and in the place where the former stood, docks, or rather basons, extremely capacious and commodious, are formed, for the reception of shipping. The ground about the town is very low and marshy, and cut into a number of fine canals——into some of which, ships of the largest size may enter——and in one of which, vessels of great burthen may ride, even close to Bruges. The harbour here is so fortunately circumstanced, that it was once thought, by Engineers, entirely secure from a blockade; and its pristine strength can in no way be so well described, as by a relation of the defence it made in the four first years of the seventeenth century——though, near the close of the sixteenth, it was no better than an insignificant fishing town. It held out against the Spaniards for three years, two months and sixteen days. Eighty thousand men lost their lives before it, while fifty thousand were killed or died within. It at last surrendered, but on good terms; and not for want of men or provisions, but for want of ground to stand on, which the enemy took from them, at an amazing loss, step by step, till they had not room left for men to defend it.Three hundred thousand cannon-balls, of thirty pounds weight each, were fired against it; and the besieged often filled up the breaches made in their ramparts with heaps of dead bodies.

Such, my dear boy, are the miracles that men, animated with the all-subduing spirit of Liberty, can perform——Liberty!that immediate jewel of the soul——that first moving principle of all the animal creation——which, with equal power, influences the bird to beat the cage with its wings, and the lion to tear the bars of his imprisonment——the infant to spring from the tender confinement of its nurse, and the lean and shrivelled pantaloon to crawl abroad, and fly the warmth and repose of his wholesome chamber——Liberty!which, for centuries enthralled by artifice and fraud, or lulled into a slumber by the witching spirit of Priest-craft, now rises like a giant refreshed with wine——in its great efforts for emancipation, destroys and overturns systems——but, when finding no resistance, and matured by time, will, I sincerely hope, sink appeased into a generous calm, and become the blessing, the guardian and protector of Mankind!

It is your good fortune, my dear children, to be born at a time when Liberty seems to be well understood in your own Country, and is universally the prevalent passion of men. It is almost needless, therefore, for me to exhort you to make it the groundwork of your political morality: but let me remind you to guard, above all, against the despotism of certain Tyrants, to whom many of the greatest advocates for Liberty are strangely apt to submit——I mean, your passions.Of all other Tyrants, they are the most subtle, the most bewitching, the most overbearing, and, what is worse, the most cruel.Beneath the domination of other Despots, tranquillity may alleviate the weight of your chains, and soften oppression; but when once you become the slave of your passions, your peace is for ever fled, and you live and die in unabating misery.

LETTER V.

The pride of the English is remarked all over the globe, even to a proverb! But pride is a word of such dubious meaning, so undefined in its sense, and strained to such various imports, that you shall hear it violently execrated by one, and warmly applauded by another——this denouncing it as a sin of the first magnitude, and that maintaining it to be the most vigilant guardian of human virtue. Those differences in opinion arise not from any defect in the intellects of either, but from each viewing the subject in that one point in which it first strikes his eye, or best suits his taste, his feeling, or his prejudices. I have no doubt, however, but a full consideration of the subject would shew, that pride, as it is called, is only good or bad as the object from which it arises is mean or magnificent, culpable or meritorious. That noble pride which stimulates to extraordinary acts of generosity and magnanimity, such as, in many instances, has distinguished, above all others, the Nobility of Spain, exacts the homage and admiration of Mankind: But I fear very much that our English pride is of another growth, and smells too rankly of that overstrained commercial spirit which makes the basis of the present grandeur of Great Britain, but which, in my humble judgment, raises only to debase her——by slow, subtle degrees, poisons the national principle, enslaves the once bold spirit of the People, detracts from their real solid felicity, and, by confounding the idea of national wealth with that of national prosperity, leads it in rapid strides to its downfall. In short, we are approaching, I fear, with daily accelerated steps, to the disposition and sordid habits of the Dutch, of whom Doctor Goldsmith so very pertinently and truly speaks, when he says,

Without leading your mind through a maze of disquisition on this subject, which might fatigue with abstruseness and prolixity, I will bring you back to the point from which the matter started, and content myself with remarking, that the pride of the English, speaking of it as a part of the national character, is the meanest of all pride. The inflation of bloated, overgrown wealth, an overweening affection for money, an idolatrous worship of gain, have absolutely confounded the general intellect, and warped the judgment of the many to that excess, that, in estimating men or things, they refer always to “what is he worth?”or, “what will it fetch?”This sordid habit of thinking was finely hit off by a keen fellow, the native of a neighbouring Kingdom, who, for many years, carried on business in London, and failed:——Sitting one day in a coffee-house in the City, where some wealthy Citizens were discussing a subject not entirely unconnected with cash concerns, one of them observing him rather attentive to their conversation, turned to him, and said, “What is your opinion, Sir, of the matter?”—“’s blood, Sir!”returned he, peevishly, “what opinion can a man have in this Country, who has not a guinea in his pocket?”

Under the influence of all the various caprices inspired by this unhappy purse-pride, I am sorry to say our Countrymen do, when they go abroad, so play the fool, that they are universally flattered and despised, pillaged and laughed at, by all persons with whom they have any dealing. In France, Mi Lor Anglois is, or at least was, to have fix times as great a profusion of every thing as any other person, and pay three hundred per cent. more for it; and the worst of it was, that a Mi Lor was found so conducive to their interest, that they would not, if they could help it, suffer any Englishman to go without a title——nay, would sometimes, with kindly compulsion, force him to accept of it, whether he would or not: but if an Englishman be, above all others, the object of imposition in foreign countries, certainly none pillage him so unmercifully as his own Countrymen who are settled there.In all the places through which I have travelled, I have had occasion to remark (and the remark has been amply verified by every Gentleman I have ever conversed with on the subject), that the most extravagant houses of entertainment are those kept by Englishmen.At Ostend, as well as other places, it was so: therefore, as economy, when it does not trespass upon the bounds of genteel liberality, is the best security for happiness and respect, I advise you, whenever you shall have occasion to visit the Continent, in the first place to avoid all appearance of the purse-proud ostentation of John Bull; and, in the next place, to avoid all English houses of entertainment.

It is a singular circumstance, and belongs, I should suppose, peculiarly to Ostend, that the charity-children of the town are permitted to come on board the vessels arrived, to beg of the passengers, one day in the week.

Before I bid adieu to Ostend, I must remark one heavy disadvantage under which it labours——the want of fresh water; all they use being brought from Bruges. In going from Ostend to Bruges, a traveller has it in his choice to go by land, or water——If by land, he gets a good voiture for about ten shillings of our money; the road is about fourteen or fifteen miles——If by water (the mode which I adopted, as by far the cheapest and the pleasantest), he travels in a vessel pretty much resembling our Lord Mayor’s barge, sometimes called a trackschuyt, but often la barquela barque, or barke: it is, in truth, fitted up in a style of great neatness, if not elegance; stored with a large stock of provisions and refreshments of all kinds, and of superior quality, for the accommodation of the passengers; and has, particularly, a very handsome private room between decks, for the company to retire to, in order to drink tea, coffee, &c.&c.or play at cards.In this comfortable, I might say, delightful vehicle, as perfectly at ease as lying on a couch in the best room in London, are passengers drawn by two horses, at the rate of about four miles an hour, for about ten pence, the same length of way that it would cost ten shillings to be jumbled in a voiture over a rough paved road.

The country between Ostend and Bruges is very level, and of course destitute of those charms to a mind of taste, which abound in countries tossed by the hand of Nature into hill, dale, mountain and valley: the whole face of it, however, is, or at least then was, in so high a state of cultivation, and so deeply enriched by the hands of art and industry, aided by the natural fertility of the soil, that its appearance, though far from striking or delightful, was by no means unpleasant; and on approaching the town of Bruges, we passed between two rows of trees, beautiful, shady, and of lofty size—forming, with the surrounding objects, a scene, which, if not romantic, was at least picturesque.

In passing through Countries groaning beneath the despotic scourge of unlimited Monarchy, where subsidies are raised, and taxes laid on ad libitum——where guilty distrust and suspicion, with the eyes of a lynx and the fangs of a harpy, stand sentinels at every gate, to scrutinize the harmless passenger, awake him to the clanks of his fetters, and awe him into compliance, a free-born Briton feels a cold horror creep through his whole frame: his soul recoils at the gloomily ferocious and insolently strict examination, with which a sentinel, at the entry of a town, stops, investigates, demands a passport; and, in short, puts him, pro tempore, in a state of durance, with all its hideous formalities and appendages, its gates, its bars, its armed ruffians, its formal professions of laws, and its utter violation of reason and of justice.Entering the town of Bruges, we were stopped by a sentinel, who, with all the saucy, swaggering air of authority, of a slave in office, demanded to know, whether we had any contraband goods?whether we were in any military capacity?whence we came?and whither we were going?with a variety of other interrogatories, to my mind equally impertinent and detestable, but which seemed to make no greater impression on the good Flemings themselves, than demanding the toll at a turnpike-gate would make on an English waggoner.

Talking over this subject, since that time, with a Gentleman who is well acquainted with all those places, he informed me, that in the war between the Emperor and the States General, some French officers, travelling through Flanders to join Count Maillebois, were stopped at the gate of Bruges, and, by order of the Emperor, sent to his army, turned into the ranks, and obliged to do duty as common soldiers. —Here, my dear Frederick, was an act, not only despotic in itself, but aggravated by circumstances of collateral profligacy, of such enormous magnitude as bids defiance to all power of amplification, and leaves eloquence hopeless of describing it with greater force than it derives from a simple narration of the fact: on the one hand, the inroad upon the just personal rights of the individual; on the other, the rights of a Nation violated. Some men in England, judging from their own constitutional security, may disbelieve the fact: but let them consider, that the Marquis de la Fayette, an alien, taken upon neutral ground, is now, even now, held in illegal, unjust thraldom and persecution——let them, I say, remember this, and let their incredulity cease.

Bless your stars, my dear boy, that you were born in a Country where such outrages as these can never be perpetrated by any, and will never be approved of but by a few

LETTER VI.

In my last, I carried you past a ferocious, impertinent sentinel, into the town of Bruges; and now, having got you there, I must endeavour, from the loose materials I have been able to collect, to give you a short description of it.

I had heard much of Bruges, its grandeur and its opulence; you will guess my surprise then, when, on entering it, I found nothing but an old-fashioned, ill-built, irregular town; the streets, in general, narrow and dirty, and most of the houses strongly expressive of poverty and squalid wretchedness: yet this was anciently a most flourishing city. Did the difference between the town at this time, and its state as it is represented of old, consist only in its external appearance, we might readily account for that, in the great improvements made by the Moderns in the art of house-building; but its present inferiority goes deeper, and is the result of departed commerce——commerce, that fluctuating will-with-a-wisp, that leads States in hot pursuit after it, to entrap them ultimately into mires and precipices, and which, when caught, stays till it extinguishes the spirit of Freedom in a Nation, refines its People into feeble slaves, and there leaves them to poverty and contempt.

Perhaps there is no subject that affords an ampler field for a speculative mind to expatiate upon, than the various, and, I may say, incongruous revolutions which have chequered the progress of human society from the first records of History down to the present time. It is indeed a speculation which not only tends to improve the understanding, by calling in experience to correct the illusions of theory, but is highly instructive in a moral point of view, by pointing out the instability of the very best strictures of human wisdom, and teaching us how little reliance is to be placed upon human casualties, or earthly contingencies. Look to Greece, once, the fountain-head of Arts, Eloquence, and Learning, and the mother of Freedom——her Poets, her Legislators, her Soldiers, and her Patriots, even to this day considered the brightestbrightest examples of earthly glory! ——see her now sunk in slavery, ignorance, sloth, and imbecillity, below any petty Nation of Europe. Look to Rome—in her turn, the queen of Arms and Arts, the land of Liberty, the nurse of Heroes—the stage on which inflexible Patriots, accomplished Philosophers, and a free People, acted for centuries a drama that elevated Man almost above his nature! ——see her now reduced to the last stage of contemptibility——even below it, to ridicule and laughter——swayed by the most contemptible imposture, and sunk into the most despicable enslavement, both of person and opinion——the offices of her glorious Senate performed by a kind of heteroclite being, an hermaphroditical imposter, who, deducing his right from the very dregs and offscourings of superstition and fanaticism, and aided by a set of disciples worthy of such a master, rules the People, not with the terrors of the Tarpeian rock, nor yet with that which to a Roman bosom was more terrible, banishment——but with the horrors of eternal damnation! ——see her valiant, vigorous Soldiery converted into a band of feeble fidlers and music-masters, and the clangor of her arms into shrill concerts of squeaking castratoes; those places where her Cicero poured forth eloquence divine, and pointed out the paths that led to true morality——where her Brutus and her Cato marshalled the forces of Freedom, and raised the arm of Justice against Tyrants, over-run by a knavish host of ignorant, beggarly, bald-pated Friars, vomiting, to a crowd of gaping bigots, torrents of fanatical bombast, of miracles never performed, of Gods made of wood or copper, and of Saints, that, like themselves, lived by imposture and deception! ——see her triumphs and military trophies changed into processions of Priests singing psalms round wafers and wooden crucifixes; and that code of Philosophy and Religion, which operated so effectually upon the morals of her People that there was none among them found so desperate or so base as to break an oath, exchanged for the Roman Catholic branch of the Christian Faith——for dispensations for incest, indulgences for murder, fines for fornication, and an exclusive patent for adultery in their priesthood. Then look to England! ——see her, who once stooped beneath the yoke of Rome, whose Chief, Caractacus, was carried there in chains to grace his conquerorsconquerors triumphs, while herself was made the meanest of the Roman Provinces, now holding the balance of the world, the unrivalled mistress of Arms, Arts, Commerce——every thing.

It was in this irresistible mutation of things, that Bruges sunk from the high state of a most flourishing city, where there are still (unless the French have destroyed them) to be seen the remains of seventeen palaces, anciently the residences of Consuls of different Nations, each of which had distinct houses, magnificently built and furnished, with warehouses for their merchandises: and such was the power and wealth of the Citizens in those days, that it is an indubitable fact, they kept their Sovereign, the Archduke Maximilian, prisoner, affronted his servants, and abused his officers; nor would they release him until he took an oath to preserve inviolate the laws of the State.Even so late as the time I was there, Bruges had some trade——indeed as good a foreign trade as most cities in Flanders.The people seemed cheerful and happy, and the markets were tolerably supplied.

Several fine canals run in a variety of directions from Bruges: by one of them, boats can go, in the course of a summer’s day, to Ostend, Nieuport, Furnes, and Dunkirk; and vessels of four hundred tuns can float in the bason of this town. Another canal leads to Ghent, another to Damme, and another to Sluys. The water of those canals is stagnant, without the least motion; yet they can, in half an hour, be all emptied, and fresh water brought in, by means of their well-contrived sluices.This water, however, is never used for drinking, or even for culinary purposes; a better sort being conveyed through the town by pipes from the two rivers Lys and Scheldt, as in London; for which, as there, every house pays a certain tax.

Although the trade of this city has, like that of all the Low Countries, been gradually declining, and daily sucked into the vortices of British and Dutch commerce, there were, till the French entered it, many rich Merchants there, who met every day at noon in the great market-place, to communicate and transact business, which was chiefly done in the Flemish language, hardly any one in it speaking French; a circumstance that by this time is much altered——for they have been already made, if not to speak French, at least to sing Ca-ira, and dance to the tune of it too, to some purpose.

The once-famed grandeur of this city consisted chiefly, like that of all grand places in the dark periods of Popery, of the gloomy piles, the ostentatious frippery and unwieldyunwieldy masses of wealth, accumulated by a long series of Monkish imposture——of Gothic structures, of enormous size and sable aspect, filled with dreary cells, calculated to strike the souls of the ignorant and enthusiastic with holy horror, to inspire awe of the places, and veneration for the persons who dared to inhabit them, and, by enfeebling the reason with the mixed operations of horror, wonder and reverence, to fit the credulous for the reception of every imposition, however gross in conception, or bungled in execution.Those are the things which constituted the greatness and splendor of the cities of Ancient Christendom; to those has the sturdiest human vigour and intellect been forced to bend the knees: they were built to endure the outrages of time; and will stand, I am sure, long, long after their power shall have been annihilated.

What a powerful engine has superstition been, in the cunning management of Priests! How lamentable it is to think, that not only all who believed, but all who had good sense enough not to believe, should, for so many centuries, have been kept in prostrate submission to the will and dominion of an old man in Rome! ——My blushes for the folly and supineness of Mankind, however, are lost in a warm glow of transport at the present irradiation of the human mind; and though I can scarcely think with patience of that glorious, Godlike being, Henry the Second of England, being obliged by the Pope to lash himself naked at the tomb of that saucy, wicked Priest, Thomas a Becket, I felicitate myself with the reflection, that the Pope is now the most contemptible Sovereign in Europe, and that the Papal authority, which was once the terror and the scourge of the earth, is now not only not recognised, but seldom thought of, and, when thought of, only serves to excite laughter or disgust.

LETTER VII.

The town of Bruges, although the streets be, as I have already described them, so mean, narrow, dirty and irregular in general, contains, nevertheless, some few streets that are tolerable, and a few squares also that are far from contemptible. ——I should think it, nevertheless, not worth another letter of description, were it not that the Churches, and Church-curiosities, demand our attention; for you will observe, that in all rich Popish Countries, every Church is a holy toy-shop, or rather a museum, where pictures, statues, gold cups, silver candlesticks, diamond crucifixes, and gods, of various sorts and dimensions, are hoarded up, in honour of the Supreme Being. This city having been for centuries the See of a Bishop, who is Suffragan to the Archbishop of Mechlin, and at the same time Hereditary Chancellor of Flanders, it is not to be wondered at, if ecclesiastical industry should have amassed some of those little trinkets which constitute the chief or only value of their Church. The mitre of this place conveys to the head that wears it a diocese containing six cities, from the names of which you will be able to form some small judgment of the opulence of one poor son of abstinence and mortification.——Those cities are, in the first place, Bruges itself, then Ostend, Sluys, Damme, Middleburgh in Flanders, and Oudenberch——not to mention one hundred and thirty-three boroughs and villages; and if you could compute the number of inferior Clergy with which the streets and highways are filled, you would be thunder-struck.There, and in all those Popish Countries, they may be seen, with grotesque habits and bald pates, buzzing up and down like bees, in swarms, (a precious hive!)——and, with the most vehement protestations of voluntary poverty in their mouths, and eyes uplifted to Heaven, scrambling for the good things of the earth with the eagerness of a pack of hounds, and the rapacity of a whole roll of lawyers!With loaded thighs (I might say, loaded arms too, for they have large pockets even in their sleeves, for the concealment of moveables), they return to the great hive, where, contrary to the law of bees, the drone lives in idle state, and he plunders them: contrary, too, to the habits of those useful insects, they banish the queen-bee, and suffer no female to approach their cells, but keep them in contiguous hives, where, under cover of the night, they visit them, and fulfil in private that which they deny in public——the great command of Providence.

The first building in nominal rank, though by no means the first in value, is the great Cathedral, which has at least bulk, antiquity and gloominess enough to recommend it to the Faithful. It is by no means unfurnished within, though not in so remarkable a manner as to induce me to fill a Letter with it.In a word, it is an old Popish Cathedral, and cannot be supposed wanting in wealth: at the time I write, it has been standing no less a time than nine hundred and twenty-nine years, having been built in the year 865.

The next that occurs to me, as worthy of notice, is the Church of Notre Dame, or that dedicated to our Lady the Virgin Mary. This is really a beautiful structure of the kind——indeed magnificent. Its steeple is beyond conception stupendous, being so very high as to be seen at sea off Ostend, although it is not elevated in the smallest degree by any rise in the ground; for, so very flat is the whole intermediate country, that I believe it would puzzle a skilful leveller to find two feet elevation from high-water-mark at Ostend up to this city. The contents of this Church are correspondent to its external appearance——being enriched and beautified with a vast variety of sacerdotal trinkets, and fine tombs and monuments. As to the former, the vestments of that same Thomas a Becket whom I mentioned in my last, make a part of the curiosities deposited in this Church: this furious and inflexible impostor was Archbishop of Canterbury; and his struggles to enslave both the King and People of England, and make them tributary to the Pope, have canonized him, and obtained the very honourable depot I mention for his vestments. To do justice, however, to the spirit and sagacity of the Holy Fathers who have so long taken the pains to preserve them, it must be commemorated, that they are, or at least were set with diamonds, and other precious stones! Probably, among the many Priests who have, in so many centuries, had the custody of those divine relics, some one, more sagacious than the rest, might conceive, that, to lie in a Church, and be seen by the all-believing eyes of the Faithful, a little coloured glass was just as good as any precious stone, and wisely have converted the originals to some better purpose. If so, it will be some consolation to Holy Mother Church to reflect, that she has bilked the Sans-culottes, who certainly have got possession of Saint Thomas a Becket’s sacerdotal petticoats; and, if they have been sound enough to stand the cutting, have, by this time, converted them into comfortable campaigning breeches. O monstrous! wicked! abominable! ——that the Royal Mary, sister to the great Emperor Charles the Fifth, should, so long ago as the Reformation, have bought at an immense price, and deposited in the treasury of the Church of our Lady the blessed Virgin Mary, the vestments of a Saint, only to make breeches, in the year 1794, for a French soldier!The time has been, that the bare suggestion of such sacrilege would have turned the brain of half the people of Christendom: but those things are now better managed.

Of the tombs in this Church, I shall only mention two, as distinguished from the rest by their costliness, magnificence and antiquity. They are made of copper, well guilt. One of them is the tomb of Mary, heiress to the Ducal House of Burgundy; and the other, that of Charles (commonly called the Hardy), Duke of Burgundy, her father.

In Bruges there were four great Abbeys, and an amazing number of Convents and Nunneries. The buildings, I presume, yet stand; but there is little doubt that their contents, of every kind, have been, before this, put in requisition, and each part of them, of course, applied to its natural use.

The Church once belonging to the Jesuits, is built in a noble style of architecture: and that of the Dominicans has not only its external merits, but its internal value; for, besides the usual super-abundance of rich chalices, &c.it possesses some very great curiosities——

As, first, a very curious, highly wrought pulpit——beautiful in itself, but remarkable for the top being supported by wood, cut out, in the most natural, deceptive manner, in the form of ropes, and which beguile the spectator the more into a belief of its reality, because it answers the purposes of ropes.

Secondly, a picture——and so extraordinary a picture!Before I describe it, I must apprise you that your faith must be almost as great as that of a Spanish Christian to believe me——to believe that the human intellect ever sunk so low as, in the first instance, to conceive, and, in the next, to harbour and admire, such a piece.But I mistake——it has its merit; it is a curiosity——the Demon of Satire himself could not wish for a greater.

This picture, then, is the representation of a Marriage! ——but of whom? why, truly, of Jesus Christ with Saint Catharine of Sienna. Observe the congruity——Saint Catharine of Sienna lived many centuries after the translation of Jesus Christ to Heaven, where he is to sit, you know, till he comes to judge the quick and the dead! ——But who marries them? In truth, Saint Dominic, the patron of this Church! The Virgin Mary joins their hands——that is not amiss——But, to crown the whole, King David himself, who died so long before Christ was born, plays the harp at the wedding!

My dear Frederick, I shall take it as no small instance of your dutiful opinion of me to believe, that such a picture existed, and made part of the holy paraphernalia of a Temple consecrated to the worship of the Divinity: but I assure you it is a fact; and as I have never given you reason to suspect my veracity, I expect you to believe me in this instance, improbable though it seems: for such a farrago of absurdities, such a jumble of incongruities, impossibilities, bulls and anachronisms, never yet were compressed, by the human imagination, into the same narrow compass.

I protract this Letter beyond my usual length, on purpose to conclude my account of Bruges, and get once more upon the road.

The Monastery of the Carthusians, another Order of Friars, is of amazing size, covering an extent of ground not much less than a mile in circumference. The Carmelites, another Order, have a Church here, in which there is raised a beautiful monument, to the memory of Henry Jermyn, Lord Dover, a Peer of England——But the Monastery called the Dunes, a sect of the Order of Saint Barnard, is by far the noblest in the whole city: the cloisters and gardens are capacious and handsome; the apartment of the Abbot is magnificent and stately, and those of the Monks themselves unusually neat.Those poor mortified penitents, secluded from the pomps, the vanities and enjoyments of life, and their thoughts, no doubt, resting alone on hereafter, keep, nevertheless, a sumptuous table, spread with every luxury of the season——have their country-seats, where they go a-hunting, or to refresh themselves, and actually keep their own coaches.

Among the Nunneries there are two English: one of Augustinian Nuns, who are all ladies of quality, and who entertain strangers at the grate with sweetmeats and wine; the other, called the Pelicans, is of a very strict Order, and wear a coarse dress.

To conclude——In the Chapel of Saint Basil is said to be kept, in perfect preservation, the blood which Joseph of Aremethea wiped off with a sponge from the dead body of Christ. Finis coronat opus.

I fancy you have, by this time, had as much of miracles as you can well digest: I therefore leave you to reflect upon them, and improve.

LETTER VIII.

As I was going to the barquebarque, at Bruges, to take my departure for Ghent, the next town in my route, I was surprised to see a number of officious, busy, poor fellows, crowding round my effects, and seizing them——some my trunk, some my portmanteau, &c. I believe two or three to each: but my astonishment partly subsided when I was told that they were porters, who plied on the canal, and about the city, for subsistence, and only came to have the honour of carrying my baggage down to the vessel. Noting their eagerness, I could not help smiling. I know there are those, and I have heard of such, who would bluster at them: but my mirth at the bustling importance which the poor fellows affected, soon sunk into serious concern; I said within myself, “Alas, how hard must be your lot indeed!” and my imagination was in an instant back again in London, where a porter often makes you pay for a job, not in money only, but in patience also, and where the surliness of independence scowls upon his brow as he does your work. Every one of my men demanded a remuneration for his labour: one man could have easily done the work of five——-but I resolved not to send them away discontented: he is but a sordid churl that would; and I paid them to their full satisfaction. Here, my dear Frederick, let me offer you (since it occurs) my parental advice on this point——from the practice of which you will gain more solid felicity than you can possibly be aware of now: never weigh scrupulously the value of the work of the Poor; rather exceed than fall short of rewarding it: it is a very, very small thing, that will put them in good humour with you and with themselves, and relax the hard furrows of labour into the soft smile of gratitude——a smile which, to a heart of sensibility such as your’s, will, of itself, ten-thousand-fold repay you, even though the frequent practice of it should abridge you of a few of those things called pleasures, or detract a little from the weight of your purse.

Being again seated in my barquebarque, I set off for Ghent, a city lying at a distance of twenty-four miles from Bruges. I must here remark to you, that the company one meets in those vessels is not always of the first rank; it is generally of a mixed, motley kind: but to a man who carries along with him, through his travels, a love for his fellow-creatures, and a desire to see men, and their customs and manners, it is both pleasant and eligible——at least I thought it so, and enjoyed it. There were those amongst us who spoke rather loftily on that subject: I said nothing; but it brought to my mind a reflection I have often had occasion to concur in, viz. that a fastidious usurpation of dignity (happily denominated stateliness) is the never-failing mark of an upstart or a blockhead.The man of true dignity, self-erect and strong, needs not have recourse, for support, to the comparative wretchedness of his fellow-creature, or plume himself upon spurious superiority.You will understand me, however!When I say, “the man of true dignity,” I am far, very far, from meaning a lord, a squire, a banker, or a general officer——I mean a man of intrinsic worth——homo emunctæ naris——one who, in every station into which chance may throw him, feels firm in the consciousness of right——who can see and cherish merit, though enveloped and concealed behind a shabby suit of clothes——and who scorns the blown-up fool of fortune, that, without sense or sentiment, without virtue, wisdom or courage, presumes to call himself great, merely because he possesses a few acres of earth which he had neither the industry nor merit to earn, or because his great-great-great-grandfather purchased a title by perfidy to his Country, the plunder of his fellow-citizens, or the slaughter of mankind.

Although the face of that part of the Country through which we are now passing, like that of the preceding stage from Ostend to Bruges, wants diversity, it has its charms, and would be particularly delightful in the eye of an English farmer; for it is covered with the thickest verdure on each side of the canal, and the banks are decorated all along by rows of stately trees, while the fields in the back ground are cultivated to the highest degree of perfection, and bear the aspect of producing the most abundant harvest.

You will be able to form a judgment of the trifling expence of travelling in this Country, from my expences in this stage of twenty-four miles.I had an excellent dinner for about fifteen pence of our money; my passage cost me but sixteen more, amounting in all to two shillings and seven pence: compare that with travelling in England, where one cannot rise up from an indifferent dinner, in an Inn, under five shillings at the least, and you must be astonished at the disproportion.

Ghent is the capital of Flanders, and is to be reckoned among the largest cities of Europe, as it covers a space of ground of not less than seven miles in circumference; but there is not above one half of that occupied with buildings, the greater part being thrown into fields, gardens, orchards, and pleasure-grounds.Situated on four navigable rivers, and intersected into no fewer than twenty-six islands by a number of canals, which afford an easy, cheap and expeditious carriage for weighty merchandise, it may be considered, in point of local advantages for commerce, superior to most cities in Europe; while those islands are again united by about a hundred bridges, some great and some small, which contribute much to the beauty of the city.

To a man accustomed to mould his thoughts by what he sees in Great Britain, the strong fortifications that surround almost all towns on the Continent convey the most disagreeable sensations——reminding him of the first misery of Mankind, War! ——denoting, alas! too truly, the disposition of Man to violate the rights of his fellow-creatures, and manifesting the tyrannous abuse of power.On me, though trained and accustomed to military habits, this “dreadful note of preparation” had an unpleasing effect; for, though born, bred and habituated to the life of the Soldier, I find the feelings of the Citizen and the Man claim a paramount right to my heart.

Ghent was once extremely well fortified, and calculated, by nature as well as by art, to repel encroachment.It had a very strong castle, walls and ditches; and now, though not otherwise strong, the country may, by shutting up the sluices, be, for above a mile round, laid in a very short time under water.It was formerly so populous and powerful, that it declared war more than once against its Sovereign, and raised amazing armies.In the year 1587, it suffered dreadfully from all the ravages of famine, under which a number not less than three thousand of its inhabitants perished in one week.

This town is distinguished by the nativity of two celebrated characters: one was the famous John of Gaunt, son of King Edward the Third of England; the other, the Emperor Charles the Fifth, who was born there in the year 1500.

It was in this city that the Confederation of the States, well known under the title of the Pacification of Ghent, which united the Provinces in the most lasting union of interest and laws, was held: this union was chiefly owing to the vigorous, unremitted efforts of William the First, Prince of Orange, to whose valour and virtue may be attributed the independence of the United States.

In this city there were computed to be fifty companies of Tradesmen, among whom were manufactured a variety of very curious and rich cloths, stuffs, and silks: it is certain, that the woollen manufacture flourished here before it had made the smallest progress in England, whose wool they then bought.There was also a good branch of linen manufacture here, and a pretty brisk corn trade, for which it was locally well calculated.You will observe, once for all, that in speaking of this Country, I generally use the past tense; for, at present, they are utterly undone.

Ghent was the See of a Bishop, who, like the Bishop of Bruges, was Suffragan to the Archbishop of Mechlin.Thus, in most Christian Countries, are the intellects, the consciences, and the cash too, of the People, shut up and hid from the light, by Priest within Dean, and Dean within Bishop——like a ring in the hand of a conjurer, box within box——till at last they are enveloped in the great receptacle of all deception, the capacious pocket of the Archbishop.Let not sceptered Tyrants, their legions, their scaffolds, and their swords, bear all the infamy of the slavery of Mankind!Opinion, opinion, under the management of fraud and imposture, is the engine that forges their fetters!!——Jansenius, from whom the Jansenists took their name, was the first Bishop of this place; and the late Bishop, I think, may be reckoned the last.

The Municipal Government of this city is correct, and well calculated to secure internal peace and order.The chief magistrate is the High Bailiff; subordinate to whom are Burgomasters, Echivins, and Counsellors.

Ghent is not deficient in stately edifices; and, true to their system, the Holy Fathers of the Church have their share, which, in old Popish Countries, is at least nineteen twentieths. In the middle of the town is a high tower, called Belfort tower; from whence there is a delightful prospect over the whole city and its environs. Monasteries and Churches, there, are without number; besides hospitals and market-places: that called Friday’s market, is the largest of all, and is adorned with a statue of Charles the Fifth, in his imperial robes. The Stadthouse is a magnificent structure——So is the Cathedral, under which the Reverend Fathers have built a subterraneous Church. What deeds are those which shun the light! Why those Holy Patriarchs have such a desire for burying themselves, and working like moles under ground, they themselves best know, and I think it is not difficult for others to conjecture.

This Cathedral, however, is well worth attention, on account of some capital pictures it contains.The marble of the Church is remarkably fine, and the altar-piece splendid beyond all possible description; and, indeed, in all the others, there are paintings, eminent for their own excellence, and for the celebrity of the masters who painted them.

In the Monastery of St. Pierre, there is a grand library, filled with books in all languages; but it is chiefly remarkable for the superlative beauty of its ceiling, one half of which was painted by Rubens

Thus you may perceive, my dear Frederick, the charity of the Clergy!——how, in pure pity for the sins of Mankind, and in paternal care of their souls, they exact from the Laity some atonement for their crimes, and constrain them at least to repent——and, with unparalleled magnanimity, take upon themselves the vices, the gluttony, the avarice, and the sensuality, of which they are so careful to purge their fellow-creatures!

LETTER IX.

Having given you a general outline of the city of Ghent, I shall now proceed to give you an account of one of the most excellent, and certainly the most interesting, of all the curiosities in that place. It is indeed of a sort so immediately correspondent to the most exalted sensations of humanity, and so perfectly in unison with the most exquisitely sensible chords of the feeling heart, that I resolved to rescue it from the common lumber of the place, and give it to you in a fresh Letter, when the ideas excited by my former might have faded away, and left your mind more clear for the reception of such refined impressions.

On one of the many bridges in Ghent stand two large brazen images of a father and son, who obtained this distinguished mark of the admiration of their fellow-citizens by the following incidents:

Both the father and the son were, for some offence against the State, condemned to die. Some favourable circumstances appearing on the side of the son, he was granted a remission of his share of the sentence, upon certain provisions——in short, he was offered a pardon, on the most cruel and barbarous condition that ever entered into the mind of even Monkish barbarity, namely, that he would become the executioner of his father! He at first resolutely refused to preserve his life by means so fatal and detestable: This is not to be wondered at; for I hope, for the honour of our nature, that there are but few, very few sons, who would not have spurned, with abhorrence, life sustained on conditions so horrid, so unnatural. The son, though long inflexible, was at length overcome by the tears and entreaties of a fond father, who represented to him, that, at all events, his (the father’s) life was forfeited, and that it would be the greatest possible consolation to him, at his last moments, to think, that in his death he was the instrument of his son’s preservation. The youth consented to adopt the horrible means of recovering his life and liberty: he lifted the axe; but, as it was about to fall, his arm sunk nerveless, and the axe dropped from his hand!Had he as many lives as hairs, he would have yielded them all, one after the other, rather than again even conceive, much less perpetrate, such an act.Life, liberty, every thing, vanished before the dearer interests of filial affection: he fell upon his father’s neck, and, embracing him, triumphantly exclaimed, “My father, my father!we will die together!”and then called for another executioner to fulfil the sentence of the law.

Hard must be their hearts indeed, bereft of every sentiment of virtue, every sensation of humanity, who could stand insensible spectators of such a scene——A sudden peal of involuntary applauses, mixed with groans and sighs, rent the air.The execution was suspended; and on a simple representation of the transaction, both were pardoned: high rewards and honours were conferred on the son; and finally, those two admirable brazen images were raised, to commemorate a transaction so honourable to human nature, and transmit it for the instruction and emulation of posterity.The statue represents the son in the very act of letting fall the axe.

Lay this to your mind, my dear Frederick: talk over it to your brother; indulge all the charming sympathetic sensations it communicates: never let a mistaken shame, or a false idea (which some endeavour to impress) that it is unmanly to melt at the tale of woe, and sympathize with, our fellow-creatures, stop the current of your sensibility——no!Be assured, that, on the contrary, it is the true criterion of manhood and valour to feel; and that the more sympathetic and sensible the heart is, the more nearly it is allied to the Divinity.

I am now on the point of conducting you out of Austrian Flanders——One town only, and that comparatively a small one, lying between Us and Brabant: the name of this town is Alost, or, as the Flemings spell it, Aelst.