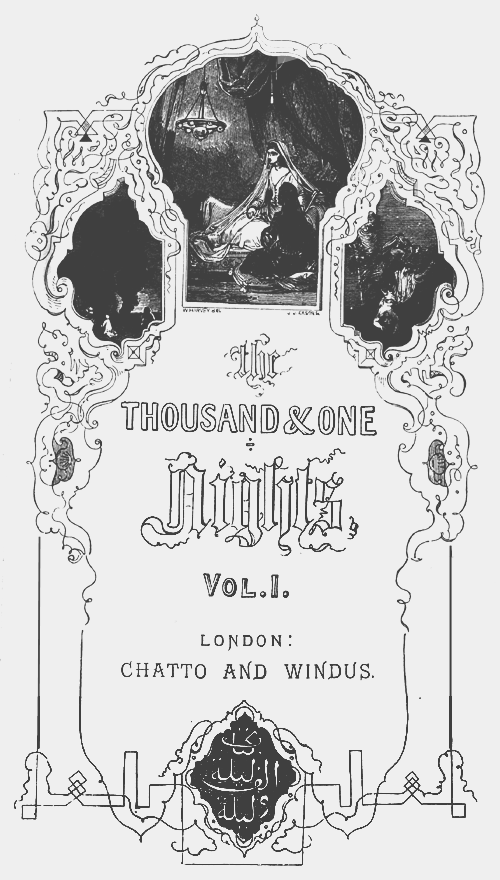

The Thousand and One Nights, Vol. I. / Commonly Called the Arabian Nights' Entertainments

Play Sample

Now he had a cock, with fifty hens under him, and he had also a dog; and he heard the dog call to the cock, and reproach him, saying, Art thou happy when our master is going to die? The cock asked, How so? —and the dog related to him the story; upon which the cock exclaimed, By Allah! our master has little sense: I have fifty wives; and I please this, and provoke that; while he has but one wife, and cannot manage this affair with her: why does he not take some twigs of the mulberry-tree, and enter her chamber, and beat her until she dies or repents? She would never, after that, ask him a question respecting anything. —And when the merchant heard the words of the cock, as he addressed the dog, he recovered his reason, and made up his mind to beat her. —Now, said the Wezeer to his daughter Shahrazád, perhaps I may do to thee as the merchant did to his wife. She asked, And what did he? He answered, He entered her chamber, after he had cut off some twigs of the mulberry-tree, and hidden them there; and then said to her, Come into the chamber, that I may tell thee the secret while no one sees me, and then die:—and when she had entered, he locked the chamber-door upon her, and beat her until she became almost senseless and cried out, I repent:—and she kissed his hands and his feet, and repented, and went out with him; and all the company, and her own family, rejoiced; and they lived together in the happiest manner until death.

When the Wezeer's daughter heard the words of her father, she said to him, It must be as I have requested.So he arrayed her, and went to the King Shahriyár.Now she had given directions to her young sister, saying to her, When I have gone to the King, I will send to request thee to come; and when thou comest to me, and seest a convenient time, do thou say to me, O my sister, relate to me some strange story to beguile our waking hour:41—and I will relate to thee a story that shall, if it be the will of God, be the means of procuring deliverance.

Her father, the Wezeer, then took her to the King, who, when he saw him, was rejoiced, and said, Hast thou brought me what I desired? He answered, Yes. When the King, therefore, introduced himself to her, she wept; and he said to her, What aileth thee? She answered, O King, I have a young sister, and I wish to take leave of her. So the King sent to her; and she came to her sister, and embraced her, and sat near the foot of the bed; and after she had waited for a proper opportunity, she said, By Allah! O my sister, relate to us a story to beguile the waking hour of our night. Most willingly, answered Shahrazád, if this virtuous King permit me. And the King, hearing these words, and being restless, was pleased with the idea of listening to the story; and thus, on the first night of the thousand and one, Shahrazád commenced her recitations.

NOTES TO THE INTRODUCTION.

Note 1.—On the Initial Phrase, and on the Mohammadan Religion and Laws. It is a universal custom of the Muslims to write this phrase at the commencement of every book, whatever may be the subject, and to pronounce it on commencing every lawful act of any importance. This they do in imitation of the Ḳur-án (every chapter of which, excepting one, is thus prefaced), and in accordance with a precept of their Prophet. The words which I translate "Compassionate" and "Merciful" are both derived from the same root, and have nearly the same meaning: the one being of a form which is generally used to express an accidental or occasional passion or sensation; the other, to denote a constant quality: but the most learned of the 'Ulamà (or professors of religion and law, &c.) interpret the former as signifying "Merciful in great things;" and the latter, "Merciful in small things." Sale has erred in rendering them, conjunctly, "Most merciful."

In the books of the Muslims, the first words, after the above phrase, almost always consist (as in the work before us) of some form of praise and thanksgiving to God for his power and goodness, followed by an invocation of blessing on the Prophet; and in general, when the author is not very concise in these expressions, he conveys in them some allusion to the subject of his book.For instance, if he write on marriage, he will commence his work with some such form as this (after the phrase first mentioned)—"Praise be to God, who hath created the human race, and made them males and females," &c.

The exordium of the present work, showing the duty imposed upon a Muslim by his religion, even on the occasion of his commencing the composition or compilation of a series of fictions, suggests to me the necessity of inserting a brief prefatory notice of the fundamental points of his faith, and the principal laws of the ritual and moral, the civil, and the criminal code; leaving more full explanations of particular points to be given when occasions shall require such illustrations.

The confession of the Muslim's faith is briefly made in these words:—"There is no deity but God: Moḥammad is God's Apostle:"—which imply a belief and observance of everything that Moḥammad taught to be the word or will of God.In the opinion of those who are commonly called orthodox, and termed "Sunnees" (the only class whom we have to consider; for they are Sunnee tenets and Arab manners which are described in this work in almost every case, wherever the scene is laid), the Mohammadan code is founded upon the Ḳur-án, the Traditions of the Prophet, the concordance of his principal early disciples, and the decisions which have been framed from analogy or comparison.This class consists of four sects, Ḥanafees, Sháfe'ees, Málikees, and Ḥambelees; so called after the names of their respective founders.The other sects, who are called "Shiya'ees" (an appellation particularly given to the Persian sect, but also used to designate generally all who are not Sunnees), are regarded by their opponents in general nearly in the same light as those who do not profess El-Islám (or the Mohammadan faith); that is, as destined to eternal or severe punishment.

The Mohammadan faith embraces the following points:

1.Belief in God, who is without beginning or end, the sole Creator and Lord of the universe, having absolute power, and knowledge, and glory, and perfection.

2.Belief in his Angels, who are impeccable beings, created of light; and Genii (Jinn), who are peccable, created of smokeless fire.The Devils, whose chief is Iblees, or Satan, are evil Genii.

3.Belief in his Scriptures, which are his uncreated word, revealed to his prophets.Of these there now exist, but held to be greatly corrupted, the Pentateuch of Moses, the Psalms of David, and the Gospels of Jesus Christ; and, in an uncorrupted and incorruptible state, the Ḳur-án, which is held to have abrogated, and to surpass in excellence, all preceding revelations.

4.Belief in his Prophets and Apostles;12 the most distinguished of whom are Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Moḥammad. Jesus is held to be more excellent than any of those who preceded him; to have been born of a virgin, and to be the Messiah, and the word of God, and a Spirit proceeding from Him, but not partaking of his essence, and not to be called the Son of God. Moḥammad is held to be more excellent than all; the last and greatest of prophets and apostles; the most excellent of the creatures of God.

5.Belief in the general resurrection and judgment, and in future rewards and punishments, chiefly of a corporeal nature: that the punishments will be eternal to all but wicked Mohammadans; and that none but Mohammadans will enter into a state of happiness.

6.Belief in God's predestination of all events, both good and evil.

The principal Ritual and Moral Laws are on the following subjects, of which the first four are the most important.

1. Prayer (eṣ-ṣaláh, commonly pronounced eṣ-ṣalah), including preparatory purifications. There are partial or total washings to be performed on particular occasions which need not be mentioned. The ablution which is more especially preparatory to prayer (and which is called wuḍoó) consists in washing the hands, mouth, nostrils, face, arms (as high as the elbow, the right first), each three times; and then the upper part of the head, the beard, ears, neck, and feet, each once. This is done with running water, or from a very large tank, or from a lake, or the sea. —Prayers are required to be performed five times in the course of every day; between daybreak and sunrise, between noon and the 'aṣr (which latter period is about mid-time between noon and nightfall), between the 'aṣr and sunset, between sunset and the 'eshè (or the period when the darkness of night commences), and at, or after, the 'eshè. The commencement of each of these periods is announced by a chant (called adán), repeated by a crier (muëddin) from the mád'neh, or menaret, of each mosque; and it is more meritorious to commence the prayer then than at a later time. On each of these occasions, the Muslim has to perform certain prayers held to be ordained by God, and others ordained by the Prophet; each kind consisting of two, three, or four "rek'ahs;" which term signifies the repetition of a set form of words, chiefly from the Ḳur-án, and ejaculations of "God is most Great!" &c. , accompanied by particular postures; part of the words being repeated in an erect posture; part, sitting; and part, in other postures: an inclination of the head and body, followed by two prostrations, distinguishing each rek'ah. These prayers may in some cases be abridged, and in others entirely omitted. Other prayers must be performed on particular occasions. 1. On Friday, the Mohammadan Sabbath. These are congregational prayers, and are similar to those of other days, with additional prayers and exhortations by a minister, who is called Imám, or Khaṭeeb.2.On two grand annual festivals.3.On the nights of Ramaḍán, the month of abstinence.4.On the occasion of an eclipse of the sun or moon.5.For rain.6.Previously to the commencement of battle.7.In pilgrimage.8.At funerals.

2.Alms-giving.An alms, called "zekáh," commonly pronounced "zekah," is required by law to be given annually, to the poor, of camels, oxen (bulls and cows), and buffaloes, sheep and goats, horses and mules and asses, and gold and silver (whether in money or in vessels, ornaments, &c.), provided the property be of a certain amount, as five camels, thirty oxen, forty sheep, five horses, two hundred dirhems, or twenty deenárs.The proportion is generally one-fortieth, which is to be paid in kind, or in money, or other equivalent.

3.Fasting (eṣ-ṣiyám).The Muslim must abstain from eating and drinking, and from every indulgence of the senses, every day during the month of Ramaḍán, from the first appearance of daybreak until sunset, unless physically incapacitated.—On the first day of the following month, a festival, called the Minor Festival, is observed with public prayer, and with general rejoicing, which continues three days.

4.Pilgrimage (el-ḥajj).It is incumbent on the Muslim, if able, to perform, at least once in his life, the pilgrimage to Mekkeh and Mount 'Arafát.The principal ceremonies of the pilgrimage are completed on the 9th of the month of Zu-l-Ḥejjeh: on the following day, which is the first of the Great Festival, on the return from 'Arafát to Mekkeh, the pilgrims who are able to do so perform a sacrifice, and every other Muslim who can is required to do the same: part of the meat of the victim he should eat, and the rest he should give to the poor.This festival is observed otherwise in a similar manner to the minor one, above mentioned; and lasts three or four days.

The less important ritual and moral laws may here be briefly mentioned in a single paragraph.—One of these is circumcision, which is not absolutely obligatory.—The distinctions of clean and unclean meats are nearly the same in the Mohammedan as in the Mosaic code.Camels' flesh is an exception; being lawful to the Muslim.Swine's flesh, and blood, are especially condemned; and a particular mode of slaughtering animals for food is enjoined, accompanied by the repetition of the name of God.—Wine and all inebriating liquors are strictly forbidden.—So also are gaming and usury.—Music is condemned; but most Muslims take great delight in hearing it.—Images and pictures representing living creatures are contrary to law.—Charity, probity in all transactions, veracity (excepting in a few cases), and modesty, are virtues indispensable.—Cleanliness in person, and decent attire, are particularly required.Clothes of silk, and ornaments of gold or silver, are forbidden to men, but allowed to women: this precept, however, is often disregarded.—Utensils of gold and silver are also condemned: yet they are used by many Muslims.—The manners of Muslims in society are subject to particular laws or rules, with respect to salutations, &c.

Of the Civil Laws, the following notices will at present suffice.—A man may have four wives at the same time, and, according to common opinion, as many concubine slaves as he pleases.—He may divorce a wife twice, and each time take her back again; but if he divorce her a third time, or by a triple sentence, he cannot make her his wife again unless by her own consent, and by a new contract, and after another man has consummated a marriage with her, and divorced her.—The children by a wife and those by a concubine slave inherit equally, if the latter be acknowledged by the father.Sons inherit equally: so also do daughters; but the share of a daughter is half that of a son.One-eighth is the share of the wife or wives of the deceased if he have left issue, and one-fourth if he have left no issue.A husband inherits one-fourth of his wife's property if she have left issue, and one-half if she have left no issue.The debts and legacies of the deceased must be first paid.A man may leave one-third of his property in any way he pleases.—When a concubine slave has borne a child to her master, she becomes entitled to freedom on his death.—There are particular laws relating to commerce.Usury and monopoly are especially condemned.

Of the Criminal Laws, a few only need here be mentioned. Murder is punishable by death, or by a fine to be paid to the family of the deceased, if they prefer it. —Theft, if the property stolen amount to a quarter of a deenár, is to be punished by cutting off the right hand, except under certain circumstances. —Adultery, if attested by four eye-witnesses, is punishable by death (stoning): fornication, by a hundred stripes, and banishment for a year. —Drunkenness is punished with eighty stripes. —Apostasy, persevered in, by death.

Note 2—On the Arabian System of Cosmography. The words translated "as a bed" would be literally rendered "and the bed;" but the signification is that which I have expressed. (See the Ḳur-án, ch. lxxviii. v. 6; and, with respect to what is before said of the heavens, idem, ch. xiii. v. 2.13) These, and the preceding words, commencing with "the Beneficent King," I have introduced (in the place of "the Lord of all creatures") from the Calcutta edition of the first two hundred nights, as affording me an opportunity to explain here the Arabian system of Cosmography, with which the reader of this work cannot be too early acquainted.

When we call to mind how far the Arabs surpassed their great master, Aristotle, in natural and experimental philosophy, and remember that their brilliant discoveries constituted an important link between those of the illustrious Greek and of our equally illustrious countryman, Roger Bacon, their popular system of cosmography becomes an interesting subject for our consideration.

According to the common opinion of the Arabs (an opinion sanctioned by the Ḳur-án, and by assertions of their Prophet, which almost all Muslims take in their literal sense), there are Seven Heavens, one above another, and Seven Earths, one beneath another; the earth which we inhabit being the highest of the latter, and next below the lowest heaven.The upper surface of each heaven, and that of each earth, are believed to be nearly plane, and are generally supposed to be circular; and are said to be five hundred years' journey in width.This is also said to be the measure of the depth or thickness of each heaven and each earth, and of the distance between each heaven or earth and that next above or below it.Thus is explained a passage of the Ḳur-án, (ch.lxv.last verse), in which it is said, that God hath created seven heavens and as many earths, or stories of the earth, in accordance with traditions from the Prophet.14—This notion of the seven heavens appears to have been taken from the "seven spheres;" the first of which is that of the Moon; the second, of Mercury; the third, of Venus; the fourth, of the Sun; the fifth, of Mars; the sixth, of Jupiter; and the seventh, of Saturn; each of which orbs was supposed to revolve round the earth in its proper sphere.So also the idea of the seven earths seems to have been taken from the division of the earth into seven climates; a division which has been adopted by several Arab geographers.—But to return to the opinions of the religious and the vulgar.

Traditions differ respecting the fabric of the seven heavens. In the most credible account, according to a celebrated historian, the first is described as formed of emerald; the second, of white silver; the third, of large white pearls; the fourth, of ruby; the fifth, of red gold; the sixth, of yellow jacinth; and the seventh, of shining light.15

Some assert Paradise to be in the seventh heaven; and, indeed, I have found this to be the general opinion of my Muslim friends: but the author above quoted proceeds to describe, next above the seventh heaven, seven seas of light; then, an undefined number of veils, or separations, of different substances, seven of each kind; and then, Paradise, which consists of seven stages, one above another; the first (Dár el-Jelál, or the Mansion of Glory), of white pearls; the second (Dár es-Selám, or the Mansion of Peace), of ruby; the third (Jennet el-Ma-wà, or the Garden of Rest), of green chrysolite; the fourth (Jennet el-Khuld, or the Garden of Eternity), of green16 coral; the fifth (Jennet en-Na'eem, or the Garden of Delight), of white silver; the sixth (Jennet el-Firdós, or the Garden of Paradise), of red gold; and the seventh (Jennet 'Adn, or the Garden of Perpetual Abode, or—of Eden), of large pearls; this overlooking all the former, and canopied by the Throne, or rather Empyrean, of the Compassionate ('Arsh Er-Raḥmán), i.e. of God. —These several regions of Paradise are described in some traditions as forming so many degrees, or stages, ascended by steps.

Though the opinion before mentioned respecting the form of the earth which we inhabit is that generally maintained by the Arabs, there have been, and still are, many philosophical men among this people who have argued that it is a globe, because, as El-Ḳazweenee says, an eclipse of the moon has been observed to happen at different hours of the night in eastern and western countries.Thus we find Ptolemy's measurement of the earth quoted and explained by Ibn-El-Wardee:—The circumference of the earth is 24,000 miles, or 8,000 leagues; the league being three miles; the mile, 3,000 royal cubits; the cubit, three spans; the span, twelve digits; the digit, five barley-corns placed side by side; and the width of the barley-corn, six mule's-hairs.El-Maḳreezee also, among the more intelligent Arabs, describes17 the globular form of the earth, and its arctic and antarctic regions, with their day of six months, and night of six months, and their frozen waters, &c.

For ourselves, however, it is necessary that we retain in our minds the opinions first stated, with regard to the form and dimensions of our earth; agreeing with those Muslims who allow not philosophy to trench upon revelation or sacred traditions.It is written, say they, that God hath "spread out the earth,"18 "as a bed,"19 and "as a carpet;"20 and what is round or globular cannot be said to be spread out, nor compared to a bed, or a carpet. It is therefore decided to be an almost plane expanse. The continents and islands of the earth are believed by the Arabs (as they were by the Greeks in the age of Homer and Hesiod) to be surrounded by "the Circumambient Ocean," "el-Baḥr el-Moḥeeṭ;" and this ocean is described as bounded by a chain of mountains called Káf, which encircle the whole as a ring, and confine and strengthen the entire fabric. With respect to the extent of the earth, our faith must at least admit the assertion of the Prophet, that its width (as well as its depth or thickness) is equal to five hundred years' journey: allotting the space of two hundred to the sea, two hundred to uninhabited desert, eighty to the country of Yájooj and Májooj (or Gog and Magog), and the rest to the remaining creatures:21 nay, vast as these limits are, we must rather extend than contract them, unless we suppose some of the heroes of this work to travel by circuitous routes. Another tradition will suit us better, wherein it is said, that the inhabited portion of the earth is, with respect to the rest, as a tent in the midst of a desert.22 But even according to the former assertion, it will be remarked, that the countries now commonly known to the Arabs (from the western extremity of Africa to the eastern limits of India, and from the southern confines of Abyssinia to those of Russia,) occupy a comparatively insignificant portion of this expanse. They are situated in the middle; Mekkeh, according to some,—or Jerusalem, according to others,—being exactly in the centre. Adjacent to the tract occupied by these countries are other lands and seas, partially known to the Arabs. On the north-west, with respect to the central point, lies the country of the Christians, or Franks, comprising the principal European nations; on the north, the country of Yájooj and Májooj, before mentioned, occupying, in the maps of the Arabs, large tracts of Asia and Europe; on the north-east, central Asia; on the east, Eṣ-Ṣeen (or China); on the south-east, the sea, or seas, of El-Hind (or India), and Ez-Zinj (or Southern Ethiopia), the waves of which (or of the former of which) mingle with those of the sea of Eṣ-Ṣeen, beyond; on the south, the country of the Zinj; on the south-west, the country of the Soodán, or Blacks: on the west is a portion of the Circumambient Ocean, which surrounds all the countries and seas already mentioned, as well as immense unknown regions adjoining the former, and innumerable islands interspersed in the latter. These terræ incognitæ are the scenes of some of the greatest wonders described in the present work; and are mostly peopled with Jinn, or Genii. On the Moḥeeṭ, or Circumambient Ocean, is the 'Arsh Iblees, or Throne of Iblees: in a map accompanying my copy of the work of Ibn-El-Wardee, a large yellow tract is marked with this name, adjoining Southern Africa. The western portion of the Moḥeeṭ is often called "the Sea of Darkness" (Baḥr eẓ-Ẓulumát, or,—eẓ-Ẓulmeh). Under this name (and the synonymous appellation of el-Baḥr el-Muẓlim) the Atlantic Ocean is described by the author just mentioned; though, in the introduction to his work, he says that the Sea of Darkness surrounds the Moḥeeṭ. The former may be considered either as the western or the more remote portion of the latter. In the dark regions (Eẓ-Ẓulumát, from which, perhaps, the above-mentioned portion of the Moḥeeṭ takes its name),23 in the south-west quarter of the earth, according to the same author, is the Fountain of Life, of which El-Khiḍr drank, and by virtue of which he still lives, and will live till the day of judgment. This mysterious person, whom the vulgar and some others regard as a prophet, and identify with Ilyás (Elias, or Elijah), and whom some confound with St. George, was, according to the more approved opinion of the learned, a just man, or saint, the Wezeer and counsellor of the first Zu-l-Ḳarneyn, who was a universal conqueror, but an equally doubtful personage, contemporary with the patriarch Ibráheem, or Abraham. El-Khiḍr is said to appear frequently to Muslims in perplexity, and to be generally clad in green garments; whence, according to some, his name. The Prophet Ilyás (or Elias) is also related to have drunk of the Fountain of Life. During the day-time, it is said, El-Khiḍr wanders upon the seas, and directs voyagers who go astray; while Ilyás perambulates the mountains or deserts, and directs persons who chance to be led astray by the Ghools:24 but at night, they meet together, and guard the rampart of Yájooj and Májooj,25 to prevent these people from making irruptions upon their neighbours. Both, however, are generally believed by the modern Muslims to assist pious persons in distress in various circumstances, whether travelling by land or by water. —The mountains of Ḳáf, which bound the Circumambient Ocean, and form a circular barrier round the whole of our earth, are described by interpreters of the Ḳur-án as composed of green chrysolite, like the green tint of the sky.26 It is the colour of these mountains, said the Prophet, that imparts a greenish hue to the sky.27 It is said, in a tradition, that beyond these mountains are other countries; one of gold, seventy of silver, and seven of musk, all inhabited by angels, and each country ten thousand years' journey in length, and the same in breadth.28 Some say that beyond it are creatures unknown to any but God:29 but the general opinion is, that the mountains of Ḳáf terminate our earth, and that no one knows what is beyond them. They are the chief abode of the Jinn, or Genii. —Such is a concise account of the earth which we inhabit, according to the notions of the Arabs.

We must now describe what is beneath our earth. —It has already been said, that this is the first, or highest, of seven earths, which are all of equal width and thickness, and at equal distances apart. Each of these earths has occupants. The occupants of the first are men, genii, brutes, &c. : the second is occupied by the suffocating wind that destroyed the infidel tribe of 'Ád: the third, by the stones of Jahennem (or Hell), mentioned in the Ḳur-án, in these words, "the fuel of which is men and stones:"30 the fourth, by the sulphur of Jahennem: the fifth, by its serpents: the sixth, by its scorpions, in colour and size like black mules, and with tails like spears: the seventh, by Iblees and his troops.31 Whether these several earths are believed to be connected with each other by any means, and if so, how, we are not expressly informed; but, that they are supposed to be so is evident. With respect to our earth in particular, as some think, it is said that it is supported by a rock, with which the mountains of Ḳáf communicate by means of veins or roots; and that, when God desires to effect an earthquake at a certain place, He commands the mountain [or rock] to agitate the vein that is connected with that place.32—But there is another account, describing our earth as upheld by certain successive supports of inconceivable magnitude, which are under the seventh earth; leaving us to infer that the seven earths are in some manner connected together.This account, as inserted in the work of one of the writers above quoted, is as follows:—The earth [under which appellation are here understood the seven earths] was, it is said, originally unstable; "therefore God created an angel of immense size and of the utmost strength, and ordered him to go beneath it, [i.e. beneath the lowest earth,] and place it on his shoulders; and his hands extended beyond the east and west, and grasped the extremities of the earth [or, as related in Ibn-El-Wardee, the seven earths], and held it [or them]. But there was no support for his feet: so God created a rock of ruby, in which were seven thousand perforations; and from each of these perforations issued a sea, the size of which none knoweth but God, whose name be exalted: then He ordered this rock to stand under the feet of the angel. But there was no support for the rock: wherefore God created a huge bull, with four thousand eyes, and the same number of ears, noses, mouths, tongues, and feet; between every two of which was a distance of five hundred years' journey: and God, whose name be exalted, ordered this bull to go beneath the rock: and he bore it on his back and his horns. The name of this bull is Kuyootà.33 But there was no support for the bull: therefore God, whose name be exalted, created an enormous fish, that no one could look upon, on account of its vast size, and the flashing of its eyes and their greatness; for it is said that if all the seas were placed in one of its nostrils, they would appear like a grain of mustard-seed in the midst of a desert: and God, whose name be exalted, commanded the fish to be a support to the feet of the bull.34 The name of this fish in Bahamoot. He placed, as its support, water; and under the water, darkness: and the knowledge of mankind fails as to what is under the darkness."35—Another opinion is, that the [seventh] earth is upon water; the water, upon the rock; the rock, on the back of the bull; the bull, on a bed of sand; the sand, on the fish; the fish, upon a still, suffocating wind; the wind, on a veil of darkness; the darkness, on a mist; and what is beneath the mist is unknown.36

It is generally believed, that, under the lowest earth, and beneath seas of darkness of which the number is unknown, is Hell, which consists of seven stages, one beneath another. The first of these, according to the general opinion, is destined for the reception of wicked Mohammadans; the second, for the Christians; the third, for the Jews; the fourth, for the Sabians; the fifth, for the Magians; the sixth, for the Idolaters; the seventh, by general consent, for the Hypocrites. "Jahennem" is the general name for Hell, and the particular name for its first stage. The situation of Hell has been a subject of dispute; some place it in the seventh earth; and some have doubted whether it be above or below the earth which we inhabit.

At the consummation of all things, God, we are told, will take the whole earth in his [left] hand, and the heavens will be rolled together in his right hand;37 and the earth will be changed into another earth; and the heavens [into other heavens];38 and Hell will be brought nigh [to the tribunal of God].39

Note 3. The phrase "God is all-knowing," or "surpassing in knowledge," or, as some say, simply "knowing," is generally used by an Arab writer when he relates anything for the truth of which he cannot vouch; and Muslims often use it in conversation, in similar cases, unless when they are uttering intentional falsehoods, which most of them are in the frequent habit of doing. It is worthy of remark, that, though falsehood is permitted by their religion in some cases, their doctors of religion and law generally condemn all works of fiction (even though designed to convey useful instruction), excepting mere fables, or apologues of a high class.

Note 4. In my usual standard-copy of the original work, as also in that from which the old translation was made, and in the edition of Breslau, this prince is called a king of the dynasty of Sásán; but as he is not so designated in the Calcutta edition of the first two hundred nights, I have here omitted, in my translation, what would render the whole work full of anachronisms.

Note 5. Shahriyár is a Persian word, signifying "Friend of the City." The name of the elder King is thus written in the Calcutta edition above mentioned: in the edition of Cairo (which I generally follow) it is written Shahrabáz, by errors in diacritical marks; and in that of Breslau, Shahrabán.

Note 6. This name, Sháh-Zemán, is a compound of Persian and Arabic, and signifies "King of the Age." By the omission of a diacritical point, in the Cairo edition, it is written Sháh-Remán.

Note 7. In the Calcutta edition before mentioned, the elder brother is called King of Samarḳand; and the younger, King of China.

Note 8.—On the title and office of Wezeer. Wezeer is an Arabic word, and is pronounced by the Arabs as I have written it; but the Turks and Persians pronounce the first letter V. There are three opinions respecting the etymology of this word. Some derive it from "wizr" (a burden); because the Wezeer bears the burdens of the King: others, from "wezer" (a refuge); because the King has recourse to the counsels of his Wezeer, and his knowledge and prudence: others, again, from "azr" (back, or strength); because the King is strengthened by his Wezeer as the human frame is by the back.40

The proper and chief duties of a Wezeer are explained by the above, and by a saying of the Prophet:—"Whosoever is in authority over Muslims, if God would prosper him, He giveth him a virtuous Wezeer, who, when he forgetteth his duty, remindeth him, and when he remembereth, assisteth him: but if He would do otherwise, He giveth him an evil Wezeer, who, when he forgetteth, doth not remind him, and when he remembereth, doth not assist him."41

The post of Wezeer was the highest that was held by an officer of the pen; and the person who occupied it was properly the next to the Sulṭán: but the Turkish Sulṭáns of Egypt made the office of Náïb (or Viceroy) to have the pre-eminence.Under them, the post of Wezeer was sometimes occupied by an officer of the sword, and sometimes by an officer of the pen; and, in both cases, the Wezeer was also called "the Ṣáḥeb."The Sulṭán Barḳooḳ so degraded this office, by intrusting its most important functions to other ministers, that the Wezeer became, in reality, the King's purveyor, and little else; receiving the indirect taxes, and employing them in the purchase of provisions for the royal kitchen.42 It is even said, that he was usually chosen, by the Turkish Sulṭáns of Egypt, from among the Copts (or Christian Egyptians); because the administration of the taxes had, from time immemorial, been committed to persons of that race.43 This, it would seem, was the case about the time of the Sulṭán Barḳooḳ. But in the present work, we are to understand the office of Wezeer as being what it was in earlier times,—that of Prime Minister; though we are not hence to infer that the editions of the Tales of a Thousand and One Nights known to us were written at a period anterior to that of the Memlook Sulṭáns of Egypt and Syria; for, in the time of these monarchs, the degradation of the office was commonly known to be a recent innovation, and it may have been of no very long continuance.

Note 9. The paragraph to which this note relates is from the Calcutta edition of the first two hundred Nights.

Note 10.—On Presents. The custom of giving presents on the occasion of paying a visit, or previously, which is of such high antiquity as to be mentioned in the book of Genesis,44 has continued to prevail in the East to this day. Presents of provisions of some kind, wax candles, &c. , are sent to a person about to celebrate any festivity, by those who are to be his guests: but after paying a mere visit of ceremony, and on some other occasions, only money is commonly given to the servants of the person visited. In either case, the latter is expected to return the compliment on a similar occasion by presents of equal value. To reject a present generally gives great offence; being regarded as an insult to him who has offered it. When a person arrives from a foreign country, he generally brings some articles of the produce or merchandise of that country as presents to his friends. Thus, pilgrims returning from the holy places bring water of Zemzem, dust from the Prophet's tomb, &c. , for this purpose. —Horses, and male and female slaves, are seldom given but by kings or great men. Of the condition of slaves in Mohammadan countries, an account will be given hereafter.

Note 11.—On the Letters of Muslims. The letters of Muslims are distinguished by several peculiarities dictated by the rules of politeness. The paper is thick, white, and highly polished: sometimes it is ornamented with flowers of gold; and the edges are always cut straight with scissors. The upper half is generally left blank: and the writing never occupies any portion of the second side. A notion of the usual style of letters will be conveyed by several examples in this work. The name of the person to whom the letter is addressed, when the writer is an inferior or an equal, and even in some other cases, commonly occurs in the first sentence, preceded by several titles of honour; and is often written a little above the line to which it apertains; the space beneath it in that line being left blank: sometimes it is written in letters of gold, or red ink.A king, writing to a subject, or a great man to a dependent, usually places his name and seal at the head of his letter.The seal is the impression of a signet (generally a ring, worn on the little finger of the right hand), upon which is engraved the name of the person, commonly accompanied by the words "His [i.e. God's] servant," or some other words expressive of trust in God, &c. Its impression is considered more valid than the sign-manual, and is indispensable to give authenticity to the letter. It is made by dabbing some ink upon the surface of the signet, and pressing this upon the paper: the place which is to be stamped being first moistened, by touching the tongue with a finger of the right hand, and then gently rubbing the part with that finger. A person writing to a superior, or to an equal, or even an inferior to whom he wishes to shew respect, signs his name at the bottom of his letter, next the left side or corner, and places the seal immediately to the right of this: but if he particularly desire to testify his humility, he places it beneath his name, or even partly over the lower edge of the paper, which consequently does not receive the whole of the impression. The letter is generally folded twice, in the direction of the writing, and enclosed in a cover of paper, upon which is written the address, in some such form as this:—"It shall arrive, if it be the will of God, whose name be exalted, at such a place, and be delivered into the hand of our honoured friend, &c. , such a one, whom God preserve." Sometimes it is placed in a small bag, or purse, of silk embroidered with gold.

Note 12. The custom of sending forth a deputation to meet and welcome an approaching ambassador, or other great man, is still observed in Eastern countries; and the rank of the persons thus employed conveys to him some intimation of the manner in which he is to be received at the court: he therefore looks forward to this ceremony with a degree of anxiety. A humorous illustration of its importance in the eye of an Oriental ambassador, is given in "The Adventures of Hajji Baba in England."

Note 13.—On Hospitality. The hospitable custom here mentioned is observed by Muslims in compliance with a precept of their Prophet. "Whoever," said he, "believes in God and the day of resurrection must respect his guest; and the time of being kind to him is one day and one night; and the period of entertaining him is three days; and after that, if he does it longer, he benefits him more; but it is not right for a guest to stay in the house of the host so long as to incommode him." He even allowed the "right of a guest" to be taken by force from such as would not offer it.45 The following observations, respecting the treatment of guests by the Bedawees, present an interesting commentary upon the former precept, and upon our text:—"Strangers who have not any friend or acquaintance in the camp, alight at the first tent that presents itself: whether the owner be at home or not, the wife or daughter immediately spreads a carpet, and prepares breakfast or dinner. If the stranger's business requires a protracted stay, as, for instance, if he wishes to cross the Desert under the protection of the tribe, the host, after a lapse of three days and four hours from the time of his arrival, asks whether he means to honour him any longer with his company. If the stranger declares his intention of prolonging his visit, it is expected that he should assist his host in domestic matters, fetching water, milking the camel, feeding the horse, &c. Should he even decline this, he may remain; but will be censured by all the Arabs of the camp: he may, however, go to some other tent of the nezel [or encampment], and declare himself there a guest. Thus, every third or fourth day he may change hosts, until his business is finished, or he has reached his place of destination."46

Note 14.—On different modes of Obeisance. Various different modes of obeisance are practised by the Muslims. Among these, the following are the more common or more remarkable: they differ in the degree of respect that they indicate, nearly in the order in which I shall mention them; the last being the most respectful:—1. Placing the right hand upon the breast. —2. Touching the lips and the forehead or turban (or the forehead or turban only) with the right hand. —3. Doing the same, but slightly inclining the head during that action. —4. The same as the preceding, but inclining the body also. —5. As above, but previously touching the ground with the right hand. —6. Kissing the hand of the person to whom the obeisance is paid. —7. Kissing his sleeve. —8. Kissing the skirt of his clothing. —9. Kissing his feet. —10. Kissing the carpet or ground before him. —The first five modes are often accompanied by the salutation of "Peace be on you!" to which the reply is, "On you be peace, and the mercy of God, and his blessings!" The sixth mode is observed by servants or pupils to masters, by the wife to the husband, and by children to their father, and sometimes to the mother. It is also an act of homage paid to the aged by the young; or to learned or religious men by the less instructed or less devout. The last mode is seldom observed but to kings; and in Arabian countries it is now very uncommon.

Note 15. It might seem unnecessary to say, that a King understood what he read, were it not explained that the style of Arabic epistolary compositions, like that of the literature in general, differs considerably from that of common conversation.

Note 16. The party travelled chiefly by night, on account of the heat of the day.

Note 17.—On the occasional Decorations of Eastern Cities. On various occasions of rejoicing in the palace of the king or governor, the inhabitants of an Eastern city are commanded to decorate their houses, and the tradesmen, in particular, to adorn their shops, by suspending shawls, brocades, rich dresses, women's ornaments, and all kinds of costly articles of merchandise; lamps and flags are attached to cords drawn across the streets, which are often canopied over; and when sufficient notice has been given, the shops, and the doors, &c. , of private houses, are painted with gay colours. —Towards the close of the year 1834, the people of Cairo were ordered to decorate their houses and shops previously to the arrival of Ibráheem Báshà, after his victorious campaigns in Syria and Asia Minor. They ornamented the lower parts of their houses with whitewash and red ochre, generally in broad, alternate, horizontal stripes; that is, one course of stone white, and the next red; but the only kind of oil-paint that they could procure in large quantities was blue, the colour of mourning; so that they were obliged to use this as the ground upon which to paint flowers and other ornamental devices on their shops; but they regarded this as portending a pestilence; and the awful plague of the following spring confirmed them in their superstitious notions.

Note 18. As the notes to this introductory portion are especially numerous, and the chase is here but cursorily alluded to, I shall reserve an account of the mode of hunting to be given on a future occasion.

Note 19.—On the opinions of the Arabs respecting Female Beauty. The reader should have some idea of the qualifications or charms which the Arabs in general consider requisite to the perfection of female beauty; for erroneous fancies on this subject would much detract from the interest of the present work. He must not imagine that excessive fatness is one of these characteristics; though it is said to be esteemed a chief essential to beauty throughout the greater part of Northern Africa: on the contrary, the maiden whose loveliness inspires the most impassioned expressions in Arabic poetry and prose is celebrated for her slender figure: she is like the cane among plants, and is elegant as a twig of the oriental willow.47 Her face is like the full moon, presenting the strongest contrast to the colour of her hair, which (to preserve the nature of the simile just employed,) is of the deepest hue of night, and descends to the middle of her back. A rosy blush overspreads the centre of each cheek; and a mole is considered an additional charm. The Arabs, indeed, are particularly extravagant in their admiration of this natural beauty-spot; which, according to its place, is compared to a globule of ambergris upon a dish of alabaster or upon the surface of a ruby.48 The eyes of the Arab beauty are intensely black, large, and long; of the form of an almond: they are full of brilliancy; but this is softened by a lid slightly depressed, and by long silken lashes, giving a tender and languid expression, which is full of enchantment, and scarcely to be improved by the adventitious aid of the black border of koḥl; for this the lovely maiden adds rather for the sake of fashion than necessity; having, what the Arabs term, natural koḥl. The eyebrows are thin and arched; the forehead is wide, and fair as ivory; the nose, straight; the mouth, small; the lips are of a brilliant red; and the teeth, "like pearls set in coral." The forms of the bosom are compared to two pomegranates; the waist is slender; the hips are wide and large; the feet and hands, small; the fingers, tapering, and their extremities dyed with the deep orange-red tint imparted by the leaves of the ḥennà.49 The person in whom these charms are combined exhibits a lively image of "the rosy-fingered Aurora:" her lover knows neither night nor sleep in her presence, and the constellations of heaven are no longer seen by him when she approaches. The most bewitching age is between fourteen and seventeen years; for then the forms of womanhood are generally developed in their greatest beauty; but many a maiden in her twelfth year possesses charms sufficient to fascinate every youth or man who beholds her.

The reader may perhaps desire a more minute analysis of Arabian beauty. The following is the most complete that I can offer him. —"Four things in a woman should be black; the hair of the head, the eyebrows, the eyelashes, and the dark part of the eyes: four white; the complexion of the skin, the white of the eyes, the teeth, and the legs: four red; the tongue, the lips, the middle of the cheeks, and the gums: four round; the head, the neck, the fore-arms, and the ankles: four long; the back, the fingers, the arms, and the legs:50 four wide; the forehead, the eyes, the bosom, and the hips: four fine; the eyebrows, the nose, the lips, and the fingers: four thick; the lower part of the back, the thighs, the calves of the legs, and the knees: four small; the ears, the breasts, the hands, and the feet."51

Note 20. Mes'ood is a common proper name of men, and signifies "happy," or "made happy."

Note 21.—On the Jinn, or Genii. The frequent mention of Genii in this work, and the erroneous accounts that have been given of these fabulous beings by various European writers, have induced me to examine the statements respecting them in several Arabic works; and I shall here offer the result of my investigation, with a previous account of the Angels.

The Muslims, in general, believe in three different species of created intelligent beings; namely, Angels, who are created of light; Genii, who are created of fire; and Men, created of earth. The first species are called "Meláikeh" (sing. "Melek"); the second, "Jinn" or "Ginn" (sing. "Jinnee" or "Ginnee"); the third, "Ins" (sing. "Insee").Some hold that the Devils (Sheyṭáns) are of a species distinct from Angels and Jinn; but the more prevailing opinion, and that which rests on the highest authority, is, that they are rebellious Jinn.

"It is believed," says El-Ḳazweenee, "that the Angels are of a simple substance, endowed with life, and speech, and reason; and that the difference between them and the Jinn and Sheyṭáns is a difference of species.Know," he adds, "that the Angels are sanctified from carnal desire and the disturbance of anger: they disobey not God in what He hath commanded them, but do what they are commanded.Their food is the celebrating of his glory; their drink, the proclaiming of his holiness; their conversation, the commemoration of God, whose name be exalted; their pleasure, his worship: they are created in different forms, and with different powers."Some are described as having the forms of brutes.Four of them are Archangels; Jebraeel or Jibreel (or Gabriel), the angel of revelations; Meekaeel or Meekál (or Michael), the patron of the Israelites; 'Azraeel, the angel of death; and Isráfeel, the angel of the trumpet, which he is to sound twice, or as some say thrice, at the end of the world: one blast will kill all living creatures (himself included): another, forty years after, (he being raised again for this purpose, with Jebraeel and Meekaeel), will raise the dead.These Archangels are also called Apostolic Angels.They are inferior in dignity to human prophets and apostles, though superior to the rest of the human race: the angelic nature is held to be inferior to the human nature, because all the Angels were commanded to prostrate themselves before Adam.Every believer is attended by two guardian and recording angels; one of whom writes his good actions; the other, his evil actions: or, according to some, the number of these angels is five, or sixty, or a hundred and sixty.There are also two Angels called Munkar (vulg.Nákir) and Nekeer, who examine all the dead, and torture the wicked, in their graves.

The species of Jinn is said to have been created some thousands of years before Adam.According to a tradition from the Prophet, this species consists of five orders or classes; namely, Jánn (who are the least powerful of all), Jinn, Sheyṭáns (or Devils), 'Efreets, and Márids.The last, it is added, are the most powerful; and the Jánn are transformed Jinn; like as certain apes and swine were transformed men.52—It must, however, be remarked here, that the terms Jinn and Jánn are generally used indiscriminately, as names of the whole species (including the other orders above mentioned), whether good or bad; and that the former term is the more common.Also, that "Sheyṭán" is commonly used to signify any evil Jinnee.An 'Efreet is a powerful evil Jinnee:53 a Márid, an evil Jinnee of the most powerful class. The Jinn (but generally speaking, evil ones) are called by the Persians "Deevs," the most powerful evil Jinn, "Narahs" (which signifies "males," though they are said to be males and females); the good Jinn, "Perees;" though this term is commonly applied to females.

In a tradition from the Prophet, it is said, "The Jánn were created of a smokeless fire."54 The word which signifies "a smokeless fire" has been misunderstood by some as meaning "the flame of fire:" El-Jóharee (in the Ṣeḥáḥ) renders it rightly; and says that of this fire was the Sheyṭán (Iblees) created. "El-Jánn" is sometimes used as a name for Iblees; as in the following verse of the Ḳur-án:—"And the Jánn [the father of the Jinn; i.e. Iblees] we had created before [i.e. before the creation of Adam] of the fire of the samoom [i.e. of fire without smoke]."55 "Jánn" also signifies "a serpent;" as in other passages of the Ḳur-án;56 and is used in the same book as synonymous with "Jinn."57 In the last sense it is generally believed to be used in the tradition quoted in the commencement of this paragraph. There are several apparently contradictory traditions from the Prophet which are reconciled by what has been above stated: in one, it is said, that Iblees was the father of all the Jánn and Sheyṭáns;58 Jánn being here synonymous with Jinn: in another, that Jánn was the father of all the Jinn;59 here, Jánn being used as a name of Iblees.

"It is held," says El-Ḳazweenee, "that the Jinn are aerial animals, with transparent bodies, which can assume various forms. People differ in opinion respecting these beings: some consider the Jinn and Sheyṭáns as unruly men; but these persons are of the Moạtezileh [a sect of Muslim freethinkers]: and some hold, that God, whose name be exalted, created the Angels of the light of fire, and the Jinn of its flame [but this is at variance with the general opinion], and the Sheytáns of its smoke [which is also at variance with the common opinion]; and that [all] these kinds of beings are [usually] invisible60 to men, but that they assume what forms they please, and when their form becomes condensed they are visible." —This last remark illustrates several descriptions of Jinnees in this work; where the form of the monster is at first undefined, or like an enormous pillar, and then gradually assumes a human shape and less gigantic size. The particular forms of brutes, reptiles, &c. , in which the Jinn most frequently appear will be mentioned hereafter.

It is said that God created the Jánn [or Jinn] two thousand years before Adam [or, according to some writers, much earlier]; and that there are believers and infidels and every sect among them, as among men.61—Some say that a prophet, named Yoosuf, was sent to the Jinn: others, that they had only preachers, or admonishers: others, again, that seventy apostles were sent, before Moḥammad, to Jinn and men conjointly.62 It is commonly believed that the preadamite Jinn were governed by forty (or, according to some, seventy-two) kings, to each of whom the Arab writers give the name of Suleymán (or Solomon); and that they derive their appellation from the last of these, who was called Jánn Ibn-Jánn, and who, some say, built the Pyramids of Egypt. The following account of the preadamite Jinn is given by El-Ḳazweenee. —"It is related in histories, that a race of Jinn, in ancient times, before the creation of Adam, inhabited the earth, and covered it, the land and the sea, and the plains and the mountains; and the favours of God were multiplied upon them, and they had government, and prophecy, and religion, and law; but they transgressed and offended, and opposed their prophets, and made wickedness to abound in the earth; whereupon God, whose name be exalted, sent against them an army of Angels, who took possession of the earth, and drove away the Jinn to the regions of the islands, and made many of them prisoners; and of those who were made prisoners was 'Azázeel [afterwards called Iblees, from his despair]; and a slaughter was made among them.At that time, 'Azázeel was young: he grew up among the Angels [and probably for that reason was called one of them], and became learned in their knowledge, and assumed the government of them; and his days were prolonged until he became their chief; and thus it continued for a long time, until the affair between him and Adam happened, as God, whose name be exalted, hath said, 'When we said unto the Angels, Worship63 ye Adam, and [all] worshipped except Iblees, [who] was [one] of the Jinn.' "64

"Iblees," we are told by another authority, "was sent as a governor upon the earth, and judged among the Jinn a thousand years, after which he ascended into heaven, and remained employed in worship until the creation of Adam."65 The name of Iblees was originally, according to some, 'Azázeel (as before mentioned); and according to others, El-Ḥárith: his patronymic is Aboo-Murrah, or Abu-l-Ghimr.66—It is disputed whether he was of the Angels or of the Jinn. There are three opinions on this point. —1. That he was of the Angels, from a tradition from Ibn-'Abbás. —2. That he was of the Sheyṭáns (or evil Jinn); as it is said in the Ḳur-án, "except Iblees, [who] was [one] of the Jinn:" this was the opinion of El-Ḥasan El-Baṣree, and is that commonly held. —3. That he was neither of the Angels nor of the Jinn; but created alone, of fire. —Ibn-'Abbás founds his opinion on the same text from which El-Ḥasan El-Baṣree derives his: "When we said unto the Angels, Worship ye Adam, and [all] worshipped except Iblees, [who] was [one] of the Jinn" (before quoted): which he explains by saying, that the most noble and honourable among the Angels are called "the Jinn," because they are veiled from the eyes of the other Angels on account of their superiority; and that Iblees was one of these Jinn. He adds, that he had the government of the lowest heaven and of the earth, and was called the Ṭáoos (literally, Peacock) of the Angels; and that there was not a spot in the lowest heaven but he had prostrated himself upon it: but when the Jinn rebelled upon the earth, God sent a troop of Angels who drove them to the islands and mountains; and Iblees being elated with pride, and refusing to prostrate himself before Adam, God transformed him into a Sheyṭán. —But this reasoning is opposed by other verses, in which Iblees is represented as saying, "Thou hast created me of fire, and hast created him [Adam] of earth."67 It is therefore argued, "If he were created originally of fire, how was he created of light? for the Angels were [all] created of light."68—The former verse may be explained by the tradition, that Iblees, having been taken captive, was exalted among the Angels; or perhaps there is an ellipsis after the word "Angels;" for it might be inferred that the command given to the Angels was also (and à fortiori) to be obeyed by the Jinn.

According to a tradition, Iblees and all the Sheyṭáns are distinguished from the other Jinn by a longer existence."The Sheyṭáns," it is added, "are the children of Iblees, and die not but with him: whereas the [other] Jinn die before him;"69 though they may live many centuries. But this is not altogether accordant with the popular belief: Iblees and many other evil Jinn are to survive mankind; but they are to die before the general resurrection; as also even the Angels; the last of whom will be the Angel of Death, 'Azraeel: yet not all the evil Jinn are to live thus long: many of them are killed by shooting stars, hurled at them from heaven; wherefore, the Arabs, when they see a shooting star (shiháb), often exclaim, "May God transfix the enemy of the faith!" —Many also are killed by other Jinn; and some, even by men. The fire of which the Jinnee is created circulates in his veins, in place of blood: therefore, when he receives a mortal wound, this fire, issuing from his veins, generally consumes him to ashes. —The Jinn, it has been already shown, are peccable. They also eat and drink, and propagate their species, sometimes in conjunction with human beings; in which latter case, the offspring partakes of the nature of both parents. In all these respects they differ from the Angels. Among the evil Jinn are distinguished the five sons of their chief, Iblees; namely, Teer, who brings about calamities, losses, and injuries; El-Aạwar, who encourages debauchery; Sóṭ, who suggests lies; Dásim, who causes hatred between man and wife; and Zelemboor, who presides over places of traffic.70

The most common forms and habitations or places of resort of the Jinn must now be described.

The following traditions from the Prophet are the most to the purpose that I have seen.—The Jinn are of various shapes; having the forms of serpents, scorpions, lions, wolves, jackals, &c.71—The Jinn are of three kinds; one on the land; one in the sea; and one in the air.72 The Jinn consist of forty troops; each troop consisting of six hundred thousand.73—The Jinn are of three kinds; one have wings, and fly; another are snakes, and dogs; and the third move about from place to place like men.74—Domestic snakes are asserted to be Jinn on the same authority.75

The Prophet ordered his followers to kill serpents and scorpions if they intruded at prayers; but on other occasions, he seems to have required first to admonish them to depart, and then, if they remained, to kill them. The Doctors, however, differ in opinion whether all kinds of snakes or serpents should be admonished first; or whether any should; for the Prophet, say they, took a covenant of the Jinn [probably after the above-mentioned command], that they should not enter the houses of the faithful: therefore, it is argued, if they enter, they break their covenant, and it becomes lawful to kill them without previous admonishment. Yet it is related that 'Áisheh, the Prophet's wife, having killed a serpent in her chamber, was alarmed by a dream, and, fearing that it might have been a Muslim Jinnee, as it did not enter her chamber when she was undressed, gave in alms, as an expiation, twelve thousand dirhems (about £300), the price of the blood of a Muslim.76

The Jinn are said to appear to mankind most commonly in the shapes of serpents, dogs, cats, or human beings.In the last case, they are sometimes of the stature of men, and sometimes of a size enormously gigantic.If good, they are generally resplendently handsome: if evil, horribly hideous.They become invisible at pleasure (by a rapid extension or rarefaction of the particles which compose them), or suddenly disappear in the earth or air, or through a solid wall.Many Muslims in the present day profess to have seen and held intercourse with them.

The Zóba'ah, which is a whirlwind that raises the sand or dust in the form of a pillar of prodigious height, often seen sweeping across the deserts and fields, is believed to be caused by the flight of an evil Jinnee.To defend themselves from a Jinnee thus "riding in the whirlwind," the Arabs often exclaim, "Iron!Iron!"(Ḥadeed!Ḥadeed!), or, "Iron!thou unlucky!"(Ḥadeed!yá mashoom!), as the Jinn are supposed to have a great dread of that metal: or they exclaim, "God is most great!"(Alláhu akbar!)77 A similar superstition prevails with respect to the water-spout at sea, as the reader may have discovered from the first instance of the description of a Jinnee in the present work, which occasions this note to be here inserted.

It is believed that the chief abode of the Jinn is in the Mountains of Ḳáf, which are supposed (as mentioned on a former occasion) to encompass the whole of our earth.But they are also believed to pervade the solid body of our earth, and the firmament; and to choose, as their principal places of resort, or of occasional abode, baths, wells, the latrina, ovens, ruined houses, market-places, the junctures of roads, the sea, and rivers.The Arabs, therefore, when they pour water, &c., on the ground, or enter a bath, or let down a bucket into a well, or visit the latrina, and on various other occasions, say, "Permission!"or "Permission, ye blessed!"(Destoor!or, Destoor yá mubárakeen!").78—The evil spirits (or evil Jinn), it is said, had liberty to enter any of the seven heavens till the birth of Jesus, when they were excluded from three of them; on the birth of Moḥammad, they were forbidden the other four.79 They continue, however, to ascend to the confines of the lowest heaven, and there listening to the conversation of the Angels respecting things decreed by God, obtain knowledge of futurity, which they sometimes impart to men, who, by means of talismans, or certain invocations, make them to serve the purposes of magical performances. To this particular subject it will be necessary to revert. —What the Prophet said of Iblees, in the following tradition, applies also to the evil Jinn over whom he presides:—His chief abode [among men] is the bath; his chief places of resort are the markets, and the junctures of roads; his food is whatever is killed without the name of God being pronounced over it; his drink, whatever is intoxicating; his muëddin, the mizmár (a musical pipe; i.e. any musical instrument); his ḳurán, poetry; his written character, the marks made in geomancy;80 his speech, falsehood; his snares are women.81

That particular Jinnees presided over particular places, was an opinion of the early Arabs.It is said in the Ḳur-án, "And there were certain men who sought refuge with certain of the Jinn."82 In the Commentary of the Jeláleyn, I find the following remark on these words:—"When they halted, on their journey, in a place of fear, each man said, 'I seek refuge with the lord of this place, from the mischief of his foolish ones!' " In illustration of this, I may insert the following tradition, translated from El-Ḳazweenee:—"It is related by a certain narrator of traditions, that he descended into a valley, with his sheep, and a wolf carried off a ewe from among them; and he arose, and raised his voice, and cried, 'O inhabitant of the valley!' whereupon he heard a voice saying, 'O wolf, restore to him his sheep!' and the wolf came with the ewe, and left her, and departed." —The same opinion is held by the modern Arabs, though probably they do not use such an invocation. —A similar superstition, a relic of ancient Egyptian credulity, still prevails among the people of Cairo. It is believed that each quarter of this city has its peculiar guardian-genius, or Agathodæmon, which has the form of a serpent.83

It has already been mentioned that some of the Jinn are Muslims; and others, infidels.The good Jinn acquit themselves of the imperative duties of religion; namely, prayers, alms-giving, fasting during the month of Ramaḍán, and pilgrimage to Mekkeh and Mount 'Arafát: but in the performance of these duties they are generally invisible to human beings.Some examples of the mode in which good Jinn pay the alms required of them by the law, I have given in a former work.84

Of the services and injuries done by Jinn to men, some account must be given.

It has been stated, that, by means of talismans, or certain invocations, men are said to obtain the services of Jinn; and the manner in which the latter are enabled to assist magicians, by imparting to them the knowledge of future events, has been explained.No man ever obtained such absolute power over the Jinn as Suleymán, Ibn-Dáood (Solomon, the Son of David).This he did by virtue of a most wonderful talisman, which is said to have come down to him from heaven.It was a seal-ring, upon which was engraved "the most great name" of God; and was partly composed of brass, and partly of iron.With the brass he stamped his written commands to the good Jinn; with the iron (for a reason before mentioned), those to the evil Jinn, or Devils.Over both orders he had unlimited power; as well as over the birds and the winds,85 and, as is generally said, the wild beasts. His Wezeer, Aṣaf the son of Barkhiyà, is also said to have been acquainted with "the most great name," by uttering which, the greatest miracles may be performed; even that of raising the dead. By virtue of this name, engraved on his ring, Suleymán compelled the Jinn to assist in building the Temple of Jerusalem, and in various other works. Many of the evil Jinn he converted to the true faith; and many others of this class, who remained obstinate in infidelity, he confined in prisons. He is said to have been monarch of the whole earth. Hence, perhaps, the name of Suleymán is given to the universal monarchs of the preadamite Jinn; unless the story of his own universal dominion originated from confounding him with those kings of the Jinn.

The injuries related to have been inflicted upon human beings by evil Jinn are of various kinds. Jinnees are said to have often carried off beautiful women, whom they have forcibly kept as their wives or concubines. I have mentioned in a former work, that malicious or disturbed Jinnees are asserted often to station themselves on the roofs, or at the windows, of houses, and to throw down bricks and stones on persons passing by.86 When they take possession of an uninhabited house, they seldom fail to persecute terribly any person who goes to reside in it. They are also very apt to pilfer provisions, &c. Many learned and devout persons, to secure their property from such depredations, repeat the words "In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful!" on locking the doors of their houses, rooms, or closets, and on covering the bread-basket, or anything containing food.87 During the month of Ramaḍán, the evil Jinn are believed to be confined in prison; and therefore, on the last night of that month, with the same view, women sometimes repeat the words above mentioned, and sprinkle salt upon the floors of the apartments of their houses.88

To complete this sketch of Arabian mythology, an account must be added of several creatures generally believed to be of inferior orders of the Jinn.

One of these is the Ghool, which is commonly regarded as a kind of Sheytán, or evil Jinnee, that eats men; and is also described by some as a Jinnee or an enchanter who assumes various forms. The Ghools are said to appear in the forms of various animals, and of human beings, and in many monstrous shapes; to haunt burial-grounds and other sequestered spots; to feed upon dead human bodies; and to kill and devour any human creature who has the misfortune to fall in their way: whence the term "Ghool" is applied to any cannibal.An opinion quoted by a celebrated author, respecting the Ghool, is, that it is a demoniacal animal, which passes a solitary existence in the deserts, resembling both man and brute; that it appears to a person travelling alone in the night and in solitary places, and, being supposed by him to be itself a traveller, lures him out of his way.89 Another opinion stated by him is this: that, when the Sheytáns attempt to hear words by stealth [from the confines of the lowest heaven], they are struck by shooting stars; and some are burnt; some, falling into a sea, or rather a large river (baḥr), become converted into crocodiles; and some, falling upon the land, become Ghools. The same author adds the following tradition:—"The Ghool is any Jinnee that is opposed to travels, assuming various forms and appearances;"90 and affirms that several of the Companions of the Prophet saw Ghools in their travels; and that 'Omar, among them, saw a Ghool while on a journey to Syria, before El-Islám, and struck it with his sword. —It appears that "Ghool" is, properly speaking, a name only given to a female demon of the kind above described: the male is called "Ḳuṭrub."91 It is said that these beings, and the Ghaddár, or Gharrár, and other similar creatures which will presently be mentioned, are the offspring of Iblees and of a wife whom God created for him of the fire of the Samoom (which here signifies, as in an instance before mentioned, "a smokeless fire"); and that they sprang from an egg.92 The female Ghool, it is added, appears to men in the deserts, in various forms, converses with them, and sometimes prostitutes herself to them.93

The Seạláh, or Saạláh, is another demoniacal creature, described by some [or rather, by most authors] as of the Jinn.It is said that it is mostly found in forests, and that when it captures a man, it makes him dance, and plays with him as the cat plays with the mouse.A man of Iṣfahán asserted that many beings of this kind abounded in his country; that sometimes the wolf would hunt one of them by night, and devour it, and that, when it had seized it, the Seạláh would cry out, "Come to my help, for the wolf devoureth me!"or it would cry, "Who will liberate me?I have a hundred deenárs, and he shall receive them!"but the people knowing that it was the cry of the Seạláh, no one would liberate it; and so the wolf would eat it.94—An island in the sea of Eṣ-Ṣeen (or China) is called "the Island of the Seạláh," by Arab geographers, from its being said to be inhabited by the demons so named: they are described as creatures of hideous forms, supposed to be Sheyṭáns, the offspring of human beings and Jinn, who eat men."95

The Ghaddár, or Gharrár (for its name is written differently in two different MSS.in my possession), is another creature of a similar nature, described as being found in the borders of El-Yemen, and sometimes in Tihámeh, and in the upper parts of Egypt.It is said that it entices a man to it, and either tortures him in a manner not to be described, or merely terrifies him, and leaves him.96

The Delhán is also a demoniacal being, inhabiting the islands of the seas, having the form of a man, and riding on an ostrich.It eats the flesh of men whom the sea casts on the shore from wrecks.Some say that a Delhán once attacked a ship in the sea, and desired to take the crew; but they contended with it; whereupon it uttered a cry which caused them to fall upon their faces, and it took them.97—In my MS. of Ibn-El-Wardee, I find the name written "Dahlán."He mentions an island called by this name, in the Sea of 'Omán; and describes its inhabitants as cannibal Sheyṭáns, like men in form, and riding on birds resembling ostriches.

The Shiḳḳ is another demoniacal creature, having the form of half a human being (like a man divided longitudinally); and it is believed that the Nesnás is the offspring of a Shiḳḳ and of a human being.The Shiḳḳ appears to travellers; and it was a demon of this kind who killed, and was killed by, 'Alḳamah, the son of Ṣafwán, the son of Umeiyeh; of whom it is well known that he was killed by a Jinnee.So says El-Ḳazweenee.

The Nesnás (above mentioned) is described as resembling half a human being; having half a head, half a body, one arm, and one leg, with which it hops with much agility; as being found in the woods of El-Yemen, and being endowed with speech: "but God," it is added, "is all-knowing."98 It is said that it is found in Ḥaḍramót as well as El-Yemen; and that one was brought alive to El-Mutawekkil: it resembled a man in form, excepting that it had but half a face, which was in its breast, and a tail like that of a sheep. The people of Ḥaḍramót, it is added, eat it; and its flesh is sweet. It is only generated in their country. A man who went there asserted that he saw a captured Nesnás, which cried out for mercy, conjuring him by God and by himself.99 A race of people whose head is in the breast is described as inhabiting an island called Jábeh (supposed to be Java), in the Sea of El-Hind, or India.100 A kind of Nesnás is also described as inhabiting the Island of Ráïj, in the Sea of Eṣ-Ṣeen, or China, and having wings like those of the bat.101

The Hátif is a being that is heard, but not seen; and is often mentioned by Arab writers.It is generally the communicator of some intelligence in the way of advice, or direction, or warning.

Here terminating this long note, I must beg the reader to remark, that the superstitious fancies which it describes are prevalent among all classes of the Arabs, and the Muslims in general, learned as well as vulgar.I have comprised in it much matter not necessary to illustrate the introductory portion of this work, in order to avoid frequent recurrence to the same subject.Another apology for its length may also be offered:—its importance as confuting Schlegel's opinion, that the frequent mention of Genii is more consistent with Indian than with Arab notions.

Note 22. This chest is described in some copies as formed of glass.

Note 23. The term "'Efreet" has been explained above, in Note 21.

Note 24. Most of the copies of the original, it appears, make the number of rings ninety-eight; therefore, I have substituted this, as less extraordinary, for five hundred and seventy, which is the number mentioned in the Cairo edition.

Note 25. Almost every Muslim who can afford it has a seal-ring, for a reason shewn in a former note (No. 11).102

Note 26. For the story of Yoosuf and Zeleekha (or Joseph and the wife of Potiphar), see the Ḳur-án, ch. xii.

Note 27.—On the wickedness of Women. The wickedness of women is a subject upon which the stronger sex among the Arabs, with an affected feeling of superior virtue, often dwell in common conversation. That women are deficient in judgment or good sense is held as a fact not to be disputed even by themselves, as it rests on an assertion of the Prophet; but that they possess a superior degree of cunning is pronounced equally certain and notorious. Their general depravity is pronounced to be much greater than that of men. "I stood," said the Prophet, "at the gate of Paradise; and lo, most of its inmates were the poor: and I stood at the gate of Hell; and lo, most of its inmates were women."103 In allusion to women, the Khaleefeh 'Omar said, "Consult them, and do the contrary of what they advise." But this is not to be done merely for the sake of opposing them; nor when other advice can be had. "It is desirable for a man," says a learned Imám, "before he enters upon any important undertaking, to consult ten intelligent persons among his particular friends; or, if he have not more than five such friends, let him consult each of them twice; or, if he have not more than one friend, he should consult him ten times, at ten different visits: if he have not one to consult, let him return to his wife, and consult her; and whatever she advises him to do, let him do the contrary: so shall he proceed rightly in his affair, and attain his object."104 A truly virtuous wife is, of course, excepted in this rule: such a person is as much respected by Muslims as she is (at least, according to their own account) rarely met with by them. When woman was created, the Devil, we are told, was delighted, and said, "Thou art half of my host, and thou art the depository of my secret, and thou art my arrow, with which I shoot, and miss not."105 What are termed by us affairs of gallantry were very common among the Pagan Arabs, and are scarcely less so among their Muslim posterity. They are, however, unfrequent among most tribes of Bedawees, and among the descendants of those tribes not long settled as cultivators. I remember being roused from the quiet that I generally enjoyed in an ancient tomb in which I resided at Thebes, by the cries of a young woman in the neighbourhood, whom an Arab was severely beating for an impudent proposal that she had made to him.