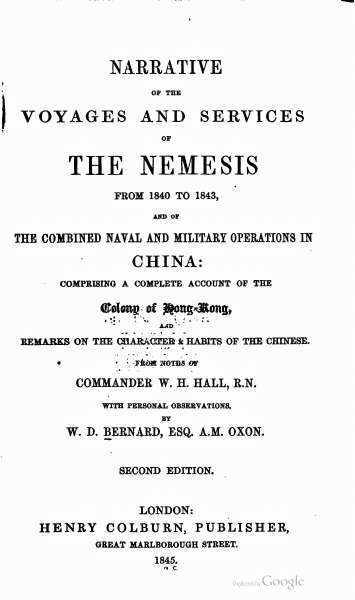

Narrative of the Voyages and Services of the Nemesis from 1840 to 1843 / And of the Combined Naval and Military Operations in China: Comprising a Complete Account of the Colony of Hong-Kong and Remarks on the Character & Habits of the Chinese. Second Edition

Summary

Play Sample

FOOTNOTE:

[9] With respect to the effects of lightning upon an iron ship, and the danger which was to be apprehended from the attraction, both of the vessel as a body, and of its particular parts as points for the electrical fluid to touch upon in its passage between the clouds and the earth, no inconvenience whatever seems to have been felt. Much had been said about it in England before her departure for a tropical region. The timid, and those less acquainted with the subject, openly expressed their apprehensions; the learned smiled with more of curiosity than fear; but the officers of the vessel itself were too busy about other matters to give themselves time to think much about the question. During their voyage to the southward, when many dangers were encountered, certainly that from lightning was amongst the least thought of; and now, as they were passing through the Mozambique Channel, a part of the world particularly famous for its heavy storms of thunder and lightning, not the slightest effect from it was observed upon the iron vessel. The funnel has a perfectly smooth top, without any ornamental points, such as are sometimes seen; and the main rigging and funnel stays were made of chain at the top, and rope throughout the rest.

CHAPTER VIII.

The present ruler, or sultan, of the Comoro Islands, by name Alloué, is the son of the late sultan Abdallah, before alluded to as having been particularly kind to distressed Englishmen.He is a young man under thirty, of moderate height, agreeable countenance, and easy, pleasant manners.But his character is not distinguished for energy, and the difficulties with which he has had to contend appear to have been rather beyond his powers.His father, Abdallah, had made a treaty with Colonel Farquhar, when governor of the Mauritius, by which he undertook to suppress, by every means in his power, the extensive trade in slaves which was at that time carried on at the islands which were under his dominion; and he particularly distinguished himself by the zeal and perfect good faith with which he carried out its provisions.Indeed, to this cause, much of the subsequent difficulties of his family, and the impoverishment of his people, seem to have been attributed.

In the latter days of Abdallah's life, he appears to have met with sad reverses; and, judging from the documents which I have been able to examine, it would seem that his determined resistance to the continuance of the slave-trade raised up enemies against him, not only in his own islands, but in the more powerful one of Madagascar, and on the coast of Africa itself.It is certain, also, that he was at all times favourably regarded by the government of Bombay, for his services to the Company's ships, and, as an acknowledgment of his assistance, a present was sent to him every three years, of a small supply of arms and ammunition.Abdallah's death was, however, at length brought about, after suffering numerous hardships, by the treacherous and cruel treatment of an emissary from Madagascar, or one of the more than half-savage chiefs of that island, into whose hands he at length fell.

This is not the place to enter at large into the subject of Madagascar history; it will be sufficient to remark that the present queen of that country is a most cruel and tyrannical sovereign; that she sets little value upon the lives or blood of her subjects, and that she is supposed to have poisoned her predecessor, the late King Radaman; further, that she did not succeed in winning the throne without sacrificing most of the chiefs who were opposed to her, and that she has since contrived to bring under her subjection many who were formerly independent governors, or chiefs, of the territory they severally occupied.Those who take an interest in missionary enterprises will also have heard of the dreadful cruelties she has exercised upon those unhappy men within her territories, most of whom were barbarously put to death, some in her presence, and partly, it is said, by her own hand.Only one or two of them escaped from the island.

Shewing the

TRACKS of the NEMESIS

W. H. HALL, R. N. COMR

1841.

Published by H. Colburn 13 GrtMarlborough Street, 1845.

Isaac Purdy Sculpt.

It was not unnatural, under these circumstances, that one or more of the chiefs of the island should have taken refuge in the neighbouring islands of Johanna and Mohilla. Accordingly, so long ago as 1828, a chief, called Raymanytek, who had been governor of an important province in Madagascar under the old king, and was said by some to be his brother, came over to Johanna with about one hundred followers, and represented to Sultan Abdallah, that he had made his escape from his own country, through fear of the queen, who sought his life, (probably he had tried to get possession of the chief authority himself,) and that, as he understood the inhabitants of the Comoro Islands were allies of the English, as well as himself, he came there to beg for an asylum.There was something very suspicious in his story; but, nevertheless, Abdallah received him in a very friendly manner, placing a house and lands at his disposal, and shewing him other civilities.

Probably, however, entertaining some mistrust of his new visitor, Abdallah sent an envoy to Bombay to make known the particulars of his arrival, and to ask whether the government would feel satisfied with his residence upon the islands under his dominion.He suspected, no doubt, that the new chief might soon become a troublesome visitor, and was anxious to endeavour to secure some further assistance from Bombay, should he stand in need of it.It is likely, also, that he wished to obtain some information respecting the character of Raymanytek.

From Bombay, reference was made to the government of the Mauritius upon the subject, as being better acquainted with the political state of Madagascar.In the meantime, the chief, not content with a residence in the neighbourhood of Sultan Abdallah, went to the opposite or southern side of the island, where he purchased a small native vessel, for the evident purpose of trading in slaves.The little craft made several voyages across to the coast of Africa; and, at length, Abdallah remonstrated with him upon the subject, and informed him that if this clandestine trade were not discontinued, he should make him leave the island altogether.To this no reply was made; and still the vessel went across to the coast, bringing back, on one occasion, nearly two hundred slaves.Many of these were probably re-exported to other parts.

Abdallah hereupon ordered his disobedient visitor immediately to quit the island, upon the ground that the slave-trade could not be permitted within his territory, the more particularly as he was bound by treaty with the English to prevent it in every way he could.

To this summons Raymanytek made no other reply than to bring all his followers together armed, and, by means of bribery and fair promises, to enlist in his cause some of the poorer inhabitants in his neighbourhood, and also to arm as many of his negro slaves as he could prevail upon, and who appeared trustworthy.Money seemed at all times to be at his command, and he is said to have brought a well-filled purse with him when he landed from Madagascar.With the force he had now collected, he made an unexpected descent upon the capital of the island, which, being unprepared, was, of course, unable to resist him.The consternation was general, in addition to which, his money is believed to have influenced some of the people to remain quiet.

Almost immediately the old Sultan Abdallah was deposed, and his brother Ali took the chief power into his hands.Abdallah, with all the rest of his family, left the island, with the hope of being able to find an opportunity of reaching some English port, where he might represent his case, and ask for assistance.He reached the island of Comoro in safety; but what became of him afterwards, until he was ultimately put to death with extreme barbarity, as before stated, I have hitherto not been able to ascertain.

During this short interval, Raymanytek had been able to get possession of the arms belonging to Abdallah, and which I have stated were supplied every two or three years by the government of Bombay, as a recompence for his friendly assistance when needed; and, having burnt and ruined the greater part of the town, and completely destroyed the crops and plantations in the neighbourhood, he embarked on board his little vessel, and, taking with him all that he could conveniently carry away of any value, he withdrew to the island of Mohilla, and established himself there in a position easy of defence; all the subsequent efforts of the rightful authorities to turn him out were of no avail.

This man must have been supplied, by some means or other, with abundance of ammunition; and it is not unlikely that his speculations in the slave-trade, by means of his own vessel, may have supplied him not only with money, but also with warlike weapons and ammunition. It is well surmised, too, that he received assistance direct from Madagascar at various times; and it must not be forgotten that the nine or ten years which elapsed between the commencement of these occurrences and the visit of the Nemesis was a period particularly fraught with difficulties in relation to the traffic in slaves, and that it appears primâ facie, highly probable that this marauding rebel may have been strongly encouraged, and even aided, in his attempts, by distant parties interested in the traffic.Indeed, unless some assistance of this kind had been furnished to him, it is difficult to see how he could so long have found means to maintain himself.

The sultan applied for assistance on several occasions to the government of the Mauritius, of the Cape, and of Bombay.The letter of the young sultan Alloué, after the death of his father, in 1836, addressed to the governor of the Cape of Good Hope, and to the admiral of the station, asking for assistance, was a really pathetic appeal to their good feelings.It detailed the horrors of poor old Abdallah's death, and the violent acts of the invader; it related the defenceless state in which he found himself on taking the reins into his hands; and then appealed to British generosity, in return for the faithful adhesion of his family to Great Britain, and the hospitality of his people towards all British subjects.

The answer on that occasion was prompt, and worthy of the cause—namely, "that in consequence of the difficulties in which the sultan of Johanna was placed, and in consideration of the fidelity with which the late Sultan Abdallah had fulfilled his engagements for the suppression of the slave-trade, and the hospitality which he had on all occasions shewn to British vessels touching at Johanna, the governor and admiral readily yield to the earnest desire of the Sultan Alloué for the aid of arms and ammunition, and send an ample supply thereof to Johanna in one of his majesty's sloops of war," &c.

With this assistance, Alloué was once more able to make head for the time against his enemy.But the country still continued in a very unsettled state; and, as the assistance was only temporary, he again fell into extreme difficulty, and addressed himself to the governor of the Mauritius upon the subject.Sir William Nicolai, who was governor and commander-in-chief of that island at that time, referred the application to the consideration of the home government.But it would seem that some little intrigues had sprung up among the sultan's own family, which it is not very easy, and so far very unimportant, to fathom.

The Sultan Alloué's uncle, Seyd Abbas, had about the same time sent two young men, either his sons or nephews, to the Mauritius, to report the unhappy state of the island, and to request assistance in support of the actual Sultan Alloué.Not long afterwards two or three other young men arrived at the Mauritius, also bearing letters from Seyd Abbas to the same purport.As this man was thought to be well disposed towards the English, and had been favourably spoken of by all those who had visited the island, and as, moreover, his object seemed to be the laudable one of trying to support the young sultan's authority, even though without his highness's acknowledged sanction, it was judged proper to maintain all these young men at the public expense, until an opportunity should offer for sending them back again. After the lapse of some months, a vessel was hired on purpose to carry them back; and it was at the same time distinctly intimated that, "however praiseworthy the intentions of Seyd Abbas may have been in sending his own relations from home as political messengers, and however high he may stand personally in the respect of Englishmen, it would in future be impossible for British authorities to maintain political correspondence with him or with any other person in Johanna than his highness the sultan of the island." The sultan was further recommended henceforth to give Seyd Abbas a share of his confidence in his councils, in consequence of his age and experience, and the apparent sincerity with which he espoused his interest; and, at the same time, the young men were recommended to his notice as very sensible and well-informed persons. The friendly interest and intentions of the government towards the sultan and people of Johanna were then in general terms expressed; and thus, with kind words and kinder hopes for better days for his subjects, the young sultan was left for the present to take care of himself.

It was only a few months before the arrival of the Nemesis that some of the events which have been recorded had occurred.The Sultan Alloué was still in extreme danger; and another letter was addressed by him to the governor of the Mauritius, only about five months previously.It appears to have been remarkably well written, and contains some ingenious observations which, as being written by a young Moorish prince, the ruler of an island in a remote corner of the globe, under circumstances of great difficulty, it may be worth while to dwell upon it for a moment.

He thanks his excellency the governor of the Mauritius for the kindness he had shewn to the young men, whom he admits to be distantly related to him; but shrewdly remarks that their "clandestine departure from Johanna, contrary to his express orders, and during the night, had given him reason to suppose that they were not quite so friendly disposed towards him as they wished his excellency to believe: and that he feared the object of their journey had been a pecuniary speculation upon the governor's goodness and British hospitality." He proceeds to express his thanks for being apprised that persons had entertained political correspondence with English authorities without his knowledge or consent; and adds, that, although he fully concurs in his excellency's opinion with regard to the age and experience of his uncle, Seyd Abbas, still there are many others in Johanna who possess the same qualities, and whose attachment and loyalty he had never had occasion to doubt

The suspicion here betrayed is self-evident, and sufficiently delicately expressed. The picture he then draws of the state of his country is a pitiable one for a prince himself to be obliged to depict—"The town burnt; the country ravaged; all our cattle killed by the chief, Raymanytek, aided by natives of Mohilla, under his orders." He distinctly intimates that the rebel chief was receiving "assistance from the French;" and, although he does not state reasonable grounds for the assertion, the statement is not altogether an improbable one, considering that the abolition of slavery in the Mauritius had roused the feeling of the French population against us and our allies: and, moreover, slavery was still in existence in the neighbouring island of Bourbon, where strong feelings against the English had been undisguisedly avowed; while, at the same time, the difficulty of procuring fresh slaves had greatly raised their price.

Intrigues were thought to have been carried on by the French traders in Madagascar itself, where they have long attempted to obtain a footing, but with little success, owing to the deadly nature of the climate. It is, however, perfectly well-known that they are still anxious to strain every nerve to establish themselves in some place eastward of the Cape, in addition to the island of Bourbon, where there is no harbour whatever, but merely an open roadstead. They are, moreover, anxious to get some point d'appui whence they may injure British trade, in case of war, in that quarter; and, at the same time, by establishing a little colony of their own, find some means of augmenting their mercantile marine.

One of their latest attempts has been at the Isle Madame; and it is perfectly well known that several other efforts have been made, and still more talked about.

If, however, Raymanytek really did receive any foreign assistance, it is not probable that it was with the knowledge or connivance of the government of Bourbon, but rather from the restless enterprise of private individuals interested in the slave trade.However that may be, there seems to be very good grounds for our hoping that the Sultan Alloué may be permitted to remain in the peaceable possession of his own rightful territories.It is our evident interest to prevent those fine islands from falling into any other hands, more especially now that the intercourse between the West and East, through the Mozambique channel, is likely to be more extensive than formerly; and that the opening for legitimate commerce, within the channel itself, cannot but attract the attention of British merchants.The trade in slaves will become yearly more difficult, and, indeed, nothing would tend more to cause its total downfall than the gradual extension, under proper government protection, of the legitimate trade in British manufactures along that coast.

The young Sultan Alloué further went on to declare in his letter that numbers of his people had been captured and taken to Mozambique and Zanzibar, where they were sold into slavery; and that several such cargoes had already been sent over.He begged earnestly that assistance might speedily be sent to him, in arms and ammunition, and that he particularly stood in need of lead and flints, and a couple of small field-pieces.At the same time, he entreated that some small vessel of war might be sent to his aid; for that such were his difficulties, that, unless speedy assistance should arrive, he feared that he should be driven to abandon the town, and seek personally an asylum in British India.He then appealed to the magnanimity of the British government, in the hope that he and his people might not be compelled to abandon their homes for want of timely assistance.[10]

Such, then, was the unhappy situation of the beautiful little island of Johanna, as described by its own prince, only a few months before the unexpected visit of the Nemesis.Little change had taken place; the town still held out, but it does not appear that any assistance had been sent to it.The very sight of the steamer gladdened the young sultan's heart, and encouraged the people, who stood greatly in need of it; the rebel chief being then at only a short distance from the town.

Late as it was, the captain and Lieut.Pedder landed in uniform to wait upon the sultan at once, as their time was so limited.One of his uncles and his prime minister received them, and accompanied them through a few narrow streets, built in the Moorish style, to the sultan's palace.At the entrance were stationed four half-clad soldiers, with muskets, as a personal guard; and, on reaching the reception room, the sultan was discovered sitting on a high-backed chair, at the further end of the apartment.He immediately rose and advanced towards them in a very friendly manner, welcoming them to Johanna with a good, hearty shake by the hand.Two chairs were placed on his left, for his guests, while, on his right, sat the governor of the town, and several other of the principal people, all on the tip-toe of expectation for the news from England, the more particularly as they were in some hope that the strange-looking "devil-ship," as they called her, might have brought a letter from the English government, in answer to his application for assistance.

They were doomed, however, to be again disappointed; but the sultan made many inquiries about the Queen and Prince Albert, and whether an heir to the throne had yet been born, and seemed not a little curious to know if the Thames Tunnel was finished.In short, he appeared to be a very well-bred and courteous young man.He alluded painfully to the distressed state of the island, and to his being surrounded by his enemies under Raymanytek, and begged hard for at least a little powder and shot, with which to endeavour to hold out until better assistance could reach him.

As it was already quite late, the interview did not last long, but promises were made to renew it on the subsequent day, and a party was arranged for an excursion outside the town on the following morning.Accordingly, at daylight, the party were again met by the king's uncle on the beach, who appointed three soldiers to act both as guides and guards.These men appeared quite pleased with the duty assigned to them, and throughout the whole trip did everything in their power to amuse the party, and to point out to them the objects best worth notice; one man went in search of shells upon the beach, another to procure fruit, and scarcely a wish was expressed that was not immediately gratified.

Having ascended the hills on the eastern side of the valley, they were gratified by a delightful prospect in every direction.The valley below was rich and capable of high cultivation, but only partially cleared of wood, and in other parts covered with long grass and low shrubs, varied by the numerous wild flowers which were then in blossom.In the rear were high and thickly-wooded mountains, picturesque in themselves, but shutting out the view of the opposite side of the island, while, in the other direction, the eye could trace the long line of picturesque coast, giving altogether a very favourable impression of the character of the island, the more particular as some of the timber is very fine, and calculated for repairing ships.

The town itself could only be viewed from the top of a higher hill behind it, which was now ascended, and its character well made out.Its little white flat-topped houses and turreted walls, with very narrow streets, pointed out its Moorish origin.But there was nothing to render it otherwise striking.

The whole population appeared to be abroad, each struggling which should gratify his curiosity the quickest, in running down to the beach to catch a glimpse of the strange vessel, the like of which none had ever seen before.Boats were seen crowding round her on all sides, and, as she lay there, decked out with all her flags, the scene was both animated and picturesque.

On descending the hill, the party were again met by the sultan's uncle, who invited them to breakfast with his highness, and accompanied them, first to his own house, where they met the sultan himself, and thence to the palace, which was close at hand. But it was still rather an early hour for a reception, and on entering the palace, it was very evident that the preparations had not yet been completed for their arrival. His highness's ladies, the sultana and her companions, had only just time to make their escape, leaving everything in disorder, and, in short, breakfast was not quite ready.

His highness was very condescending, but it was clear that his attentions were being divided between two or more objects at the same time, one of which was readily guessed to be the ladies fair, who had so suddenly decamped.But this was not the only one, and, in the little intervals between his exits and his entrances, an opportunity was taken to ask his uncle, who was present, what it was all about.The mystery was solved.His highness was condescending to superintend the preparation of the breakfast for his guests, that it might be worthy of them.The kitchen was on this occasion converted into the council-chamber, and quite as weighty matters there discussed, and certainly with equal warmth, and probably, too, with the full "ore rotundo" of hungry eloquence, as are often treated of with greater solemnity in higher conclaves.

The result, indeed, was worthy of the cause.The breakfast was pronounced capital, and ample justice done, after the morning's walk, to the wisdom of his highness's deliberations.He himself seemed quite delighted, and his uncle declared to Captain Hall, in his absence, that the young man's greatest pleasure was to contrive some new means of gratifying the English who came in his way, and that there was nothing he would not condescend to do for them, in his enthusiastic admiration of the nation.A little of this might be said and done for effect, but there has always been good reason to believe that he was on all occasions a sincere, and, in some respects, useful ally.

The same day, a grand entertainment was to be given by some relation of the Sultan's, in his uncle's house, in honour of the performance of the first Mohammedan rite upon the young infant, his son and heir, upon the eighth day after its birth.The sultan himself, with his chief minister, accompanied them to see the festivities.On this occasion, the ladies of the court were all found to be in the apartment adjoining the reception room, and only separated from it by a large screen or curtain before the door.Now, according to all the prescribed rules of civilized life, it may reasonably be supposed that the fair damsels, secluded as they usually were, had just as much curiosity to see the lions of the day, the English officers in uniform, as the latter had to catch a glimpse of eastern beauty, the more sought the more forbidden.Every now and then you could see the curtain moved gently on one side, and a young lady's head peep out; and then another would steal a quiet look on the other side; then again, by pressing against each other, more of them would be seen than they intended, but quite enough to make you wish to see more still. In the meantime his highness had retired, or perhaps they might not have been so bold.

As the gallantry of the sons of Neptune has at all times been famous, so in this instance it innocently got the better of their discretion, and, with an apparently accidental, though well-premeditated charge at the curtain, which was most gallantly pushed on one side, a full view of all the fair ladies was obtained, much more to the apparent horror of the old uncle, who was a spectator of the achievement, than to that of the fair damsels themselves, who, nevertheless, quietly retreated in some trepidation.The ladies were all very handsomely and gaudily dressed, it being a gala-day, but they were not altogether the most Venus-like of beauties.

But a more curious scene was brought to view on being conducted to another apartment, where a large and merry party of ladies of less distinguished rank were amusing themselves with dancing and singing, but certainly without much grace in the one or melody in the other.There was only one good-looking female among the whole assembly, and she appeared to be the queen of beauty, or mistress of the feast, for she was treated with the utmost attention and deference by all the rest.

On returning again to the presence of the sultan, refreshments were handed round, and, as the weather was hot, a whole train of the female servants of the house were ushered into the room, each with a fan, or sort of portable punka, in her hand.They were all very neatly and cleanly dressed, and immediately set their fans most dexterously to work, taking their stations behind each person of the party.

In the midst of this scene the sultan disappeared, followed by his uncle, and, after a few minutes' consultation, the attendance of Captain Hall was requested in his highness's private apartment.Something important was evidently about to happen, but, before there was much time to conjecture what it might be, he found himself alone with the sultan.His highness frankly confessed the alarm which the strength of the chief named Raymanytek had excited in his mind, that he was even then not far from the town, and that he himself was determined at once to march out against the rebels, if he could get a sufficient supply of powder and shot.At the same time he begged that, if necessary, he might have the assistance of the steamer to protect his town.

Only one reply could be given, namely, that the visit of the steamer was a mere casual thing, with a view to ascertain the nature of the harbour; that the service she was engaged on would admit of no delay, but that, as long as she was there, which could not be many hours more, she should give protection to himself and his family, as well as to the town, if in danger, and that a small supply of ammunition should be given to him to enable him to defend himself. He appeared quite satisfied, and pleased with the reply. At the same time, as the danger was imminent, and much blood might otherwise be shed, he requested that, since the orders by which the steamer was obliged to abide would necessitate her immediate departure, the British flag might be hoisted upon his citadel before she started, and receive the proper salute, in order to intimidate the rebel chief; and further, that a letter might be written to the latter, stating that the sultan of Johanna was an old ally of Great Britain, and that the taking up arms against him could no longer be permitted; in short, that he had, therefore, better take himself off as quickly as possible, and return to obedience.

This was a request which demanded very serious consideration.It was evident that Captain Hall had no authority whatever to interfere in the matter.And such, consequently would have been the only reply of many officers, perhaps most, under the same circumstances.But, there was now something of humanity called into play, something of pity, and something, perhaps, of pride.It was impossible not to feel a deep interest in the unhappy position of the young sultan, more particularly as he and all his family had on so many occasions behaved with kindness and humanity towards Englishmen in distress.He had, moreover, stated his positive wish to become not only the ally, but even the subject of Great Britain, and that he would rather give up the island altogether to the English, and, if necessary, retire from it elsewhere, than see it in its then state of misery from the incursions of Raymanytek.

There was, in fact, something in Alloué's appeal, which was altogether irresistible; and after much reflection, and well knowing the responsibility incurred, it was agreed that the British flag should be hoisted upon the citadel, under a salute of twenty-one guns.This was accordingly done, and for the first time, the flag, which so many millions look upon with pride, waved over the citadel and walls of Johanna.The sultan smiled, and appeared to take far greater pride in that unstained ensign, than in his own independent flag, or his own precarious authority.

Great were the rejoicings of the whole people of the town; in fact, the day had been one of continued excitement to all parties.To crown the whole, a letter was written to the rebel chief, according to the tenour of what has been stated above, and which, it was hoped, would induce Raymanytek to retire peaceably for the present, and to defer to an opportunity less favourable for himself, if not altogether to forego, his treasonable designs, which had evidently been to depose the sultan, and probably put him to death, and banish all his family, assuming the whole authority himself in his place.

This had been a long and eventful day for the Nemesis, and while we have been relating what was passing on shore, those on board had been busy taking in water and wood for the immediate continuance of the voyage.One thing, however, yet remained; the sultan was to visit the ship, and see what to him were wonders.He came on board in the afternoon, with several attendants, in full Moorish dress, and, of course, evinced the utmost astonishment at the arrangement of the ship, the machinery, &c.To him and his followers all was new.As they steamed round the bay, their wonderment increased more and more at the ease and rapidity with which she moved; and having partaken of a little fruit and bread, and taken a most friendly and, to all appearance, grateful leave of Captain Hall, and all on board, he was landed in the ship's boat, with his own flag flying upon it.

On landing, he seemed quite overwhelmed with thankfulness for the timely assistance rendered to him, and unaffectedly sorry at parting with friends, he had so recently made.

On the afternoon of the 5th September, 1840, the interesting little island of Johanna was left behind, with many good wishes for the success of the sultan's arms, and for the speedy restoration of peace and plenty to his harassed subjects.It is feared, however, that these hopes have scarcely yet been realized.[11]

FOOTNOTES:

[10] The sultan very recently went up to Calcutta, to apply to the Governor-general, in the hope that the Company might be induced to take possession of the islands, which he felt he could no longer hold without assistance. He merely asked for himself a small annual stipend out of the revenues. What answer he may have received is not known; but probably his application was rejected, upon the ground of our territory in the East being already quite large enough. But, in reality, the Comoro Islands, or at least a part of them, must be viewed in a political light, as they may be said to command the navigation of the straits, and are generally thought to be an object aimed at by the French.

[11] The following letter concerning the fate of the Comoro Islands, and the violent proceedings of the French in that quarter, appeared in The Times of January 30th, 1844. The facts stated in it have every appearance of exaggeration, but the interference of the British government would seem to be called for.

"The French have, within the last month, obtained, by fraud, possession of the islands of Johanna, Mohilla, and Peonaro; they had already, by the same means, obtained the islands of Mayotte and Nos Beh. There are at present out here eleven ships of war—the largest a 60-gun frigate; more are expected out, in preparation for the conquest of all Madagascar; and also, it is said, of the coast of Africa, from latitude 10 S. to 2 S. ; this portion includes the dominions of the Imaum of Muscat. At this place (Nos Beh) a system of slavery is carried on that you are not aware of. Persons residing here, send over to places on the mainland of Africa, as Mozambique, Angoza, &c. , money for the purchase of the slaves; they are bought there for about ten dollars each, and are sold here again for fifteen dollars; here again they are resold to French merchant vessels from Bourbon and St. Mary's for about twenty-five to thirty dollars each. Captains of vessels purchasing these use the precaution of making two or three of the youngest free, and then have them apprenticed to them for a certain term of years, (those on shore,) fourteen and twenty one years. These papers of freedom will answer for many. It is a known fact, that numbers have been taken to Bourbon, and sold for two hundred and three hundred dollars each. Those who have had their freedom granted at this place, (Nos Beh,) as well as others, are chiefly of the Macaw tribe. The Indian, of Havre, a French bark, took several from this place on the 20th of September last; she was bound for the west coast of Madagascar, St. Mary's, and Bourbon. L'Hesione, a 32-gun frigate, has just arrived from Johanna, having compelled one of the chiefs to sign a paper, giving the island up to the French. On their first application, the king and chiefs of Johanna said, that the island belonged to the English. The French then said, that if it was not given up, they would destroy the place; they, after this, obtained the signature of one of the chiefs to a paper giving up the island to the French.

"I remain, Sir, &c. , &c. ,

"Henry C.Arc Angelo.

"Supercargo of the late Ghuznee of Bombay."Nos Beh, Madagascar,

"Oct.6th, 1843."

The account given in the above letter is partly borne out by the following announcement, which appeared in the Moniteur, the French official newspaper, in March, 1844; the substance of it is here copied from The Times of the 14th March, and there can be little doubt concerning the object of the French in taking the active step alluded to. We must hope, therefore, that our interests in that quarter will be properly watched, particularly when we remember what serious injury would be inflicted upon the whole of our Eastern trade, in case of war, by the establishment of the French in good harbours to the eastward of the Cape. The announcement is as follows:—"Captain Des Fossés has been appointed Commander of the station at Madagascar, and Bourbon, which was hitherto placed under the orders of the Governor of Bourbon. This station now acquires a greater degree of importance. Captain Des Fossés having under his orders five or six ships of war, will exhibit our flag along the whole coast of Africa, and in the Arabian Seas. He will endeavour to extend our relations with Abyssinia, and our influence in Madagascar."

CHAPTER IX.

The next place towards which the Nemesis was destined to shape her course was the island of Ceylon, where at length was to be made known to her the ultimate service upon which she was to be employed.It was not until the 10th that she lost sight of Comoro island, the northernmost of the group of that name, and, if measured in a direct line, considerably less than one hundred miles from Johanna.

Horsburgh particularly notices the light, baffling winds, and the strong, south-west and southerly currents, which prevail during the months of October and November among the Comoro Islands.But it was found upon this voyage that these difficulties presented themselves sometimes much earlier than stated by him.It was now only the beginning of September, and the southerly current was found setting down at the rate of even sixty miles a day.Indeed, both the winds and currents in the Mozambique Channel had been found very different from what had been expected.It was the season of the south-west monsoon when she entered it in the month of August; and as it is usually stated that this wind continues to blow until early in November, the Nemesis ought to have had favourable winds to carry her quite through, even later in the season.On the contrary, she met with a strong head-wind, and a much stronger southerly current than she had reason to expect.

The opinion of Horsburgh seems to be fully confirmed, that late in the season it is better for ships to avoid the Mozambique Channel, and rather to proceed to the eastward of Madagascar, and then pass between Diego Garcia and the Seychelle Islands. Steamers, however, would have less need of this were coal to be had at Mozambique.

From the equator, the current was always easterly; but nothing particular occurred worth noticing, except that, as she approached the Maldive Islands, she encountered very heavy squalls, accompanied with rain.

On the following day, the 1st October, the Maldives were in sight; and, in order to carry her through them rapidly, steam was got up for a few hours, until she came to, in the afternoon, within a quarter of a mile of the shore, under one of the easternmost of the islands, named Feawar, having shaped her course straight across the middle of the long, and until lately, much dreaded group of the Maldive Archipelago.

This extensive chain or archipelago of islands lies in the very centre of the Indian Ocean, and, being placed in the direct track of ships coming from the south-west towards Ceylon, and the southern parts of Hindostan, it was long dreaded by mariners, and shunned by them as an almost impenetrable and certainly dangerous barrier.It is stated by Horsburgh, that the early traders from Europe to India were much better acquainted with these islands than modern navigators, and that they were often passed through in these days without any apprehension of danger.The knowledge of their navigable channels must therefore have been, in a great measure, lost; and, although the utmost credit is due to the indefatigable Horsburgh for his arduous efforts to restore some of the lost information, it is to the liberality of the Indian government, and particularly to the scientific labours and distinguished services of Captain Moresby and Commander Powell, of the Indian navy, that we are indebted for the minute and beautiful surveys of all these intricate channels which have been given to the world since 1835.

This archipelago is divided into numerous groups of islands, called by the natives Atolls, each comprising a considerable number of islands, some of which are inhabited, and abound in cocoa-nut trees, while the smaller ones are often mere barren rocks or sandy islets.The number of these islands, large and small, amounts to several hundred; and the groups, or Atolls, into which they are divided, are numerous.They are laid down with wonderful accuracy and minuteness by Captains Moresby and Powell; so that, with the aid of their charts, the intricate channels between them can be read with almost the same facility as the type of a book.Thus one of the greatest boons has been conferred upon navigators of all nations.They are disposed in nearly a meridian line from latitude 7° 6' N.to latitude 0° 47' S., and consequently extend over the hottest portion of the tropics, for the distance of more than three hundred and seventy miles.

As the Nemesis passed through these islands, she found that all the former difficulties had now vanished.So accurate were the soundings, and given on so large a scale, that it was more like reading a European road-book than guiding a vessel through an intricate labyrinth of islands.

The very sight of a steamer completely frightened the inhabitants of the little island of Feawar; who, although they at length came alongside without much fear, could never be persuaded to come on board the vessel.However, they had no objection to act as guides, for the purpose of shewing what was to be seen upon their island; and, while a little necessary work was being done to the vessel, Captain Hall and two or three of the officers landed, and were soon surrounded by a crowd of natives upon the beach, quite unarmed.

A stroll along the shore, covered with pieces of coral, soon brought them to a mosque and burial-ground, which was remarkable for the neatness with which it was disposed.The little ornamented head-stones, with inscriptions, and flowers in many places planted round them, probably refreshed by the sacred water of a well close at hand, proved, at all events, the great respect paid to their dead, which is common among all Mohammedans.Indeed, the inhabitants of all these numerous islands are mostly of that persuasion, and consider themselves to be under the protection of England, the common wish of almost all the little independent tribes of the East.

The village itself appeared to be at least half deserted, the poor people, particularly the women, having hastily run away, leaving their spinning-wheels at their doors.They appear to carry their produce, consisting of oil, fish, rope, mats, &c., to Ceylon and other parts of India, in large boats of their own construction, bringing back in return rice and English manufactured goods.Indeed, an extensive traffic is carried on between all the northernmost of this extensive chain of islands, or submarine mountains, and the nearer parts of the coast of India.

On the same evening, the Nemesis continued her voyage, and, on the afternoon of the 5th October, reached the harbour of Pointe de Galle, in Ceylon.She came in under steam, with about eight tons of coal remaining, having been exactly one month from Johanna.

The mystery attending the Nemesis was now to end.Scarcely had she fairly reached her moorings, when a despatch was delivered to the captain from the government of India, containing orders from the Governor-general in council, to complete the necessary repairs, and take in coal and provisions, with all possible expedition, and then to proceed to join the fleet off the mouth of the Canton River, placing himself under the orders of the naval commander-in-chief.

Great was now the rejoicing of both officers and men.Her captain had already been made acquainted with his destination, as far as Ceylon, before leaving England, but no one on board, until now, had any certain information as to what particular service they were to undertake afterwards.The road to distinction was now made known to them; they were at once to be engaged in active operations, in conjunction with her majesty's forces.

Notwithstanding, however, the unremitted exertions of all on board, the Nemesis could not be got ready to proceed on her voyage in less than eight clear days from the time of her arrival at Pointe de Galle.Added to this, the whole of the stores and supplies had to be sent by land from Columbo, a distance of seventy-two miles, as it was not then so well known that all these things could be readily obtained at Singapore, and that therefore a smaller quantity would have sufficed.Indeed, from the more frequent communication with Ceylon, through vessels touching at Pointe de Galle for supplies, which has since taken place, every provision has now been made at that port, without the necessity of sending for stores to so great a distance as Columbo.

Under all circumstances, no time was to be lost; and the anxiety to proceed on the voyage as quickly as possible was so great, that Captain Hall determined to start off for Columbo the same evening, in order to wait upon his Excellency the Governor, and expedite the sending on of the requisite stores.A highly respectable merchant, Mr. Gibb, who was going over, kindly offered him a seat in his gig, and, after considerable exertion and fatigue, they arrived at Columbo late on the following evening.

On the following morning, the country presented itself in all the rich tropical aspect of these regions.The whole road to Columbo pointed out a fertile and luxuriant country, and was in itself admirably adapted for travelling.

For my own part, the more I have seen of tropical countries, the more I have everywhere been fascinated by their luxuriance, and enjoyed the brilliancy of their skies. There is much to compensate for the occasional oppression of the heat, which, after all, is less troublesome or injurious than the chilling blasts of northern climes; and, generally speaking, with proper precaution, it has been hardly a question with myself whether the average degree of health and buoyancy of spirits is not far greater than in less favoured though more hardy regions. Every day that passes is one in which you feel that you really live, for every thing around you lives and thrives so beautifully. Nevertheless, it must not be forgotten that, after a few years spent in so relaxing a climate the constitution becomes enfeebled, and is only to be restored by a visit to more bracing regions.

Governor Mackenzie seemed to take much interest in the steamer, and in her probable capabilities for the peculiar service likely to be required of her in China; he had evidently made the subject his study, and upon this, as upon other questions, evinced great intelligence.

Little need here be said about the island of Ceylon, which has been recently so well described and treated of by able and well-informed writers.The fine fortifications of Columbo, (the capital of the island,) the governor's palace, the barracks and public offices, are all worth seeing; indeed, it is to be regretted that arrangements have not yet been made, by which the steamers from Calcutta to the Red Sea, touching at Point de Galle, might allow some of their passengers, instead of wasting the valuable time necessary for taking in fuel at Point de Galle, to cross over to Columbo.The steamers might then, with a very trifling additional expense, touch at Columbo to pick them up, together with other passengers likely to be found there, now that the overland route is daily becoming more frequented.

The most curious sight at Columbo is the little fleet of fishing-boats, in the shape of long, narrow canoes, each made out of the single trunk of a tree, with upper works rigged on to them, falling in in such a way, that there is just sufficient room for a man's body to turn round.They start off with the land-wind in the morning, and run out a long distance to fish, returning again with the sea-breeze in the afternoon.Both ends are made exactly alike, so that, instead of going about, they have only to shift the large lug-sail, the mast being in the middle, and it is quite indifferent which end of the boat goes foremost.To counteract the natural tendency of so narrow a body to upset, two slight long spars are run out at the side, connected at the outer ends by a long and stout piece of wood, tapering at either extremity, not unlike a narrow canoe; this acts as a lever to keep the boat upright, and is generally rigged out upon the windward side.If the breeze freshens, it is easy to send a man or two out upon it, as an additional counterpoise by their weight, and there they sit, without any apparent apprehension.

The healthiness of Ceylon is within the last few years greatly improved, principally owing to the extensive clearing of land which has taken place.The plantations of coffee having been found at one time, as indeed they are still, to yield a very large profit, induced a great number of persons to enter into the speculation.Land was readily purchased from government as quickly as it could be obtained, at the rate of five shillings an acre; and the result has been a considerable increase in the exports of the island, as well as an amelioration of its condition.

Coals, provisions, and stores of all kinds, were sent on board the Nemesis with the utmost expedition, and, on the afternoon of the 14th October, she was once more ready for sea.The public interest in the events gradually growing up out of the negotiations which were then being carried on with the Chinese had gradually been raised to a high pitch, and a passage to China, to join the force as a volunteer, was readily provided for the governor's son, Lieutenant Mackenzie.Crowds of people gathered upon the shore in all directions to witness her departure, and the discharge of a few signal-rockets as soon as it was dark added a little additional novelty to the event.

Ten days sufficed to carry the Nemesis to the island of Penang, or Prince of Wales's island.Her passage had been longer than might have been expected, owing in a great measure to the badness of the coal, which caked and clogged up the furnaces in such a way that, instead of requiring to be cleaned out only once in about twenty-four hours, as would have been the case with good coal, it was necessary to perform this process no less than four times within the same period; added to which, the enormous quantity of barnacles which adhered to her bottom (a frequent source of annoyance before) greatly retarded her progress.

The island of Penang, which lies close upon the coast of the peninsula of Malacca, from which it is separated by a channel scarcely more than two miles broad, would seem to be a place particularly adapted for steamers to touch at.Indeed, it has become a question of late whether it should not be provided with a sort of government dockyard, for the repair of the increased number of ships of war and transports, both belonging to the service of government and the East India Company, which will necessarily have to pass through the straits of Malacca, now that our intercourse with China is so rapidly increasing.The harbour is perfectly safe, the water at all times smooth; coals can easily be stored there, and good wood can be obtained on the spot; moreover, it lies directly in the track of ships, or very little out of it, as they generally prefer passing on the Malacca side of the straits, particularly during the south-west monsoon.The heavy squalls which prevail on the opposite coast are so severe, that they have at length taken its very name, and are called Sumatras.They are accompanied with terrific lightning, which often does great mischief, and they are justly looked upon with great dread.

Penang is very properly considered one of the loveliest spots in the eastern world, considering its limited extent; and, from the abundance and excellence of its spice productions, which come to greater perfection in the straits than in any other part in which they have been tried, (except, perhaps, in the island of Java,) this little island has proved to be an extremely valuable possession. It abounds in picturesque scenery, heightened by the lovely views of the opposite coast of Malacca, called Province Wellesley, which also belongs to the East India Company. The numerous and excellent roads, the hospitality of the inhabitants, and the richness of the plain, or belt, which lies between the high, wooded mountains in the rear, and the town and harbour are, perhaps, unequalled. This plain, together with the sides of some of the adjoining mountains, is covered with luxuriant plantations of nutmegs, cocoa-nut-trees, and spice-trees of all kinds; and altogether Penang is one of the most attractive, as it is also one of the healthiest spots in the East. It has by some been even called the "Gem of the Eastern seas." There is a fort not far from the fine, covered jetty, or landing-place, of considerable strength; and, with very moderate trouble and expense, there is little doubt that Penang could be made a valuable naval depôt.

The short passage down the straits of Malacca, towards Singapore, was easily performed in three days.But here again some detention was inevitable.The north-east monsoon had already fairly set in, and as vessels proceeding up the China Sea, at this season, would have the wind directly against them, it was necessary that the steamer should take in the greatest possible quantity of fuel she could carry, before she could venture to leave Singapore.On this occasion, every spare corner that could be found was filled with coal, and even the decks were almost covered with coal-bags.By this means, she was enabled to carry enough fuel for full fifteen days' consumption, or about one hundred and seventy-five tons.

The small island of Singapore being situated just off the southern extremity of the peninsula of Malacca, from which it is separated only by a very narrow strait, must necessarily lie almost directly in the track of all vessels passing up or down the straits of Malacca, either to or from China, or any of the intermediate places.Being easy of access to all the numerous half-civilized tribes and nations which inhabit the islands of those seas, and within the influence of the periodical winds or monsoons which, at certain seasons, embolden even the Chinese, Siamese, and other nations to venture upon the distant voyage, it is not surprising that in the space of a few years it should have risen to a very high degree of importance as a commercial emporium.

The wisdom of the policy of Sir Stamford Raffles, in establishing a free port in such an advantageous position, has been proved beyond all previous anticipation.The perfect freedom of commercial intercourse, without any restriction or charges of any kind, has given birth to a yearly increasing commercial spirit among all the surrounding nations. It is impossible to see the immense number of curious junks and trading-vessels which arrive from all parts during the proper season, without admiring the enterprising commercial spirit of all those different tribes, and acknowledging the immense value to England of similar distant outports, for the security and extension of her commerce.

The intercourse with Singapore has been rapidly increasing every year, but especially since the commencement of the war in China.Of course, all our ships of war and transports touch at so convenient a place, where supplies of every description can easily be obtained, and where every attention and kindness are shewn to strangers, both by the authorities and by the resident merchants.Much credit is due to the late governor, Mr. Bonham, for the intelligence and activity which he exhibited, in everything that could in any way forward the objects of the expedition, and for the readiness with which he endeavoured to meet all the wishes of those who were concerned in it.His hospitality and personal attention was acknowledged by all.

In some respects, Singapore forms a good introduction to a first visit to China.It has a very large Chinese population, (not less than 20,000,) to which yearly additions are made, on the arrival of the large trading junks, in which they come down voluntarily to seek employment.Hundreds of them arrive in the greatest destitution, without even the means of paying the boat-hire to enable them to reach the shore, until they are hired by some masters.They are the principal mechanics and labourers of the town, and also act as household servants, while many of them are employed in the cultivation of spices and of sugar, or in clearing land.There is no kind of labour or employment which a Chinaman will not readily undertake; and they appear to succeed equally well in all, with the exception of tending sheep or cattle, which is an occupation they are little fond of.

The town has something of a Chinese aspect, from the number of Chinamen who are employed in every capacity; and the fruits and vegetables are principally cultivated and brought to market by people of that nation. In Java, Penang, and elsewhere, they are also to be met with in great numbers; which is quite sufficient to prove (were proof wanting) how much they are naturally disposed to become a colonizing people. There is hardly any part of the world to which a Chinaman would refuse to go, if led and managed by some of his own countrymen. But, wherever they go, they carry the vice of opium-smoking with them, and it is needless to say that it thrives at Singapore to its fullest extent, and that a large revenue is annually derived from the monopoly of the sale of the drug.

The climate of Singapore is healthy, although the soil is wet, owing to the constant rains; and the heat is, perhaps, never excessive, although the place is situated only about seventy miles from the equator.

It might be expected that the recent opening of the new Chinese ports, from some of which large trading junks have annually come down to seek their cargoes at Singapore, would prove injurious to the future trade of the latter, since it would no longer be necessary for the Chinese to go abroad to seek for that which will now be brought to them at their own doors.This apprehension, however, seems to be little entertained on the spot, because there can be little doubt, that whatever tends to augment the general foreign trade with China must benefit Singapore, which lies on the highroad to it, to a greater or less extent.Singapore has nothing to fear as regards its future commercial prosperity, which is likely rather to increase than to diminish, in consequence of the general increase of trade with China and the neighbouring islands.

On the 4th of November, the Nemesis resumed her voyage, and passed the little rocky island of Pedra Branca early on the following morning.This dangerous and sometimes half-covered rock lies nearly in the direct track for vessels proceeding up the China Sea; and on its southern side are two dangerous ledges or reefs, running out from it to the distance of more than a mile, which, at high water, can scarcely be traced above the surface.On the opposite, or northern side, there is deep water in not less than sixteen or seventeen fathoms, close in to the rock; and, moreover, the tides in its neighbourhood are very irregular, not only in point of time, but also in direction and velocity.Nor are these the only dangers to be met with in this locality.Hence it will readily appear that a lighthouse placed upon Pedra Branca would be of essential utility to all navigators who have occasion to pass up or down the China Sea.A ship leaving Singapore for Hong-Kong, for instance, might then start at such an hour in the evening as would enable her to make the light on Pedra Branca before morning; by which means, her true position being ascertained, she might stand on without fear of any danger.The expense of erecting the lighthouse would not be great, as the elevation would only be moderate, and the expense of maintaining it might be defrayed by levying a small light-duty at Singapore upon all vessels passing up or down the China Sea.

It has been often suggested that this would be a most advantageous site for the proposed monument to the memory of the distinguished Horsburgh, to whom too much honour cannot be paid for his inestimable works, so much relied on by all navigators who frequent the eastern seas. It would be difficult to find a more advantageous or appropriate position, for the best of all monuments to his fame, than this little, dangerous island of Pedra Branca, situated as it is in the very centre of some of his most valued researches; while the recent opening of the new ports in China, and the possession of Hong-Kong, give an increased importance to subjects connected with the navigation of those seas. There is not a single vessel, either British or foreign, which traverses those regions, which is not indebted to Horsburgh for the instructions which render her voyage secure; and a lighthouse upon Pedra Branca would do no less service to navigators than it would honour to the memory of Horsburgh.

The Nemesis had now passed this rocky little island, and at once found the full strength of the north-east monsoon blowing steadily against her, so that "full steam" was necessary to enable her to proceed.On the afternoon of the 16th, the high land of the Spanish possessions of Luconia (better known by the name of the capital town, Manilla) came in sight; and, on the following morning, the Nemesis passed very near the port, but without venturing to enter it, on account of the delay which it would cause, although fuel was already much wanted.

The appearance of the island was very striking.Bold, picturesque mountains, fine woods, with here and there a few sugar plantations extending along the valleys, and rich, green, cocoa-nut groves, to vary the prospect—all these combined, or alternating with each other, made the aspect of the island very attractive.

Unfortunately, no time could be spared to visit the interior of the country, as the voyage had already been much protracted, and the north-east monsoon was blowing directly against the vessel.Her progress was therefore slow, and the want of fuel began to be much felt.

On the 24th, the Lieu-chew Islands came in sight; but these are not the same islands which were visited by Capt.Basil Hall, whose descriptions excited so much attention.[12]

At daylight on the following morning, the 25th of November, the Nemesis steamed through the Typa anchorage, which lies opposite Macao, and ran close in to the town, where the water is so shallow that none but trading-boats can venture so far.The sudden appearance of so large and mysterious-looking a vessel naturally excited the greatest astonishment among all classes, both of the Portuguese and Chinese residents.The saluting of the Portuguese flag, as she passed, sufficed to announce that something unusual had happened; and crowds of people came down to the Praya Grande, or Esplanade, to look at the first iron steamer which had ever anchored in their quiet little bay.Her very light draught of water seemed to them quite incompatible with her size; and even the Portuguese governor was so much taken by surprise, that he sent off a messenger expressly to the vessel, to warn her captain of the supposed danger which he ran by venturing so close in shore.It is probable, however, that his excellency was not quite satisfied with the near approach of an armed steamer, within a short range of his own palace; and, moreover, the firing of a salute, almost close under his windows, had speedily frightened away the fair ladies who had been observed crowding at all the windows with eager curiosity.

As soon as the first excitement had passed, Captain Hall waited upon the governor, to assure him that he had come with the most peaceable intentions, and to thank his excellency for the friendly warning he had given, with respect to the safety of the vessel.At the same time, he begged to inform his excellency, that he was already thoroughly acquainted with the harbour and anchorage of Macao, from early recollection of all those localities, as he had served as midshipman on board the Lyra, during Lord Amherst's embassy to China, in 1816.

It was now ascertained that the English admiral, the Hon.George Elliot, was at anchor with his fleet in Tongkoo roads, below the Bogue forts; and, accordingly, the Nemesis proceeded to join the squadron, after the delay of only a few hours.Her arrival was announced by the salute to the admiral's flag, which was immediately returned by the Melville, precisely as if the Nemesis had been a regular man-of-war.

The Nemesis now found herself in company with the three line-of-battle ships, Wellesley, Melville, and Blenheim, together with H.M.S.Druid, Herald, Modeste, Hyacinth, and the Jupiter troop-ship.Thus, then, after all her toil and hardships, the gallant Nemesis had at length reached the proud post towards which she had so long been struggling.Her voyage from England had, indeed, been a long one, very nearly eight months having elapsed since she bade adieu to Portsmouth.But her trials had been many during that period.She had started in the worst season of the year, and had encountered, throughout nearly the whole voyage, unusual weather and unforeseen difficulties.She had happily survived them all, and the efforts which had been already made to enable her to earn for herself a name gave happy promise of her future destiny.

The excitement on board was general, now that she at length found her iron frame swinging, side by side, with the famed "wooden walls" of England's glory; and the prospect of immediate service, in active operations against the enemy, stimulated the exertions of every individual. For some days, however, she was compelled to content herself with the unwelcome operation of "coaling" in Tongkoo Bay. In the meantime, the ships of war had sailed, leaving her to follow them as soon as she could be got ready; and now, while this black and tedious process is going on, we cannot be better employed than in taking a short survey of the events which had immediately preceded her arrival, and of the more important occurrences which led to such momentous consequences.

FOOTNOTE:

[12] Captain Hall of the Nemesis was at that time serving as midshipman under Capt. Basil Hall.

CHAPTER X.

The abolition of the privileges of the East India Company in China, and the difficulties which soon resulted therefrom, concerning the mode of conducting our negotiations with the Chinese, will be remembered by most readers; and, whatever part the questions arising out of the trade in opium, may have afterwards borne in the complication of difficulties, there is little doubt that the first germ of them all was developed at the moment when the general trade with China became free. This freedom of trade, too, was forced upon the government and the company in a great degree, by the competition of the American interests; and by the fact, that British trade came to be carried on partly under the American flag, and through American agency, because it was prevented from being brought into fair competition in the market, under the free protection of its own flag.

The unhappy death of the lamented Lord Napier, principally occasioned by the ill treatment of the Chinese, and the mental vexation of having been compelled to submit to the daily insults of the Chinese authorities, in his attempts to carry out the orders of his government, will be remembered with deep regret.With the nature of those orders we have here nothing to do.No one can question Lord Napier's talent, energy, and devotedness to the object of his mission.

The attempts of Captain Elliot, when he afterwards took upon himself the duties of chief superintendent, to carry out the same instructions, were scarcely less unfortunate. And finding, as he publicly stated, that "the governor had declined to accede to the conditions involved in the instructions which he had received from her majesty's government, concerning the manner of his intercourse with his Excellency," the British flag was struck at the factories at Canton, on the 2nd of December, 1837, and her majesty's principal superintendent retired to Macao.

During the year 1838, very serious and determined measures began to be adopted by the Chinese authorities, directed generally against the trade in opium; and imperial edicts threatened death as the punishment, for both the dealers in, and the smokers of the drug. Several unfortunate Chinese were executed in consequence. Attempts were now made to execute the criminals in front of the foreign factories along the river side, contrary to all former usage and public right. A remonstrance followed, addressed to the governor, who, in reply, gave them a sort of moral lecture, instead of a political lesson, and, then, condescendingly admitted, that "foreigners, though born and brought up beyond the pale of civilization, must yet have human hearts."

Nevertheless, in the following December, 1838, the insulting attempt was again repeated, close under the American flag-staff, which was not then placed, as it has since been, in an enclosure, surrounded with a brick wall, and high paling.The flag was immediately hauled down by the consul, in consequence of the preparations which were going on, for the erection of the cross upon which the criminal was to be strangled.

At first, a few foreigners interfered, and, without violence, induced the officers to desist from their proceedings.But, gradually, the crowd increased, and, a Chinese mob, when excited, is fully as unruly as an English one; and, thus, each imprudent act, as usual, led to another.No Chinese authorities were at hand to control the disturbance; stones began to fly in all directions; and the foreigners, who, by this time, had come forward, to the aid of their brethren, were at length, through the increasing numbers of the mob, fairly driven to take refuge in the neighbouring factories.Here they were obliged to barricade the doors and windows, many of which, were, nevertheless, destroyed, and the buildings endangered, before a sufficient force of Chinese soldiers had arrived to disperse the mob.In the evening, however, quiet was perfectly restored.

In the meantime, the alarm had spread to Whampoa, whence Captain Elliot set out, accompanied by about one hundred and twenty armed men, for Canton, and arrived at the British factory late in the evening. Both parties were now clearly placed in a false position, yet one which it would have been very difficult to have avoided. During many preceding months, the unfortunate Hong merchants had been in constant collision with their own government on the one hand, and with the foreign merchants, on the other. There was scarcely any species of indignity, to which they were not exposed, and they were even threatened with death itself. The Chinese government had daily become more overbearing towards all foreigners; and its habitual cold and haughty tone had grown into undisguised contempt and unqualified contumely. Their treatment of Lord Napier had been considered on their part as a victory; and their successful repulse of all Captain Elliot's advances, was viewed by them as an evidence of their own power, and of Great Britain's weakness.

It has been already stated in the first chapter, that Sir Frederick Maitland, who had a short time previously paid a visit to China, in a line of battle ship, had left those seas altogether, just before the collision took place; and, in proportion as the foreigners were left unprotected, so did the Chinese become more overbearing.

At the same time, it cannot be denied, that their determination to put a stop, as far as possible, to the opium-trade, was for the time sincere; though their measures might have been hasty and unwarrantable. A few days after the preceding disturbance, Captain Elliot distinctly ordered, that "all British owned schooners, or other vessels, habitually, or occasionally engaged in the illicit opium traffic, within the Bocca Tigris, should remove before the expiration of three days, and not again return within the Bocca Tigris, being so engaged." And they were, at the same time, distinctly warned, that if "any British subjects were feloniously to cause the death of any Chinaman, in consequence of persisting in the trade within the Bocca Tigris, he would be liable to capital punishment; that no owners of such vessels, so engaged, would receive any assistance or interposition from the British government, in case the Chinese government should seize any of them; and, that all British subjects, employed in these vessels, would be held responsible for any consequences which might arise from forcible resistance offered to the Chinese government, in the same manner as if such resistance were offered to their own or any other government, in their own or in any foreign country."

So far Captain Elliot evinced considerable energy and determination; but he, probably, had scarcely foreseen that the shrewd and wily government of China would very soon put the question to him, "if you can order the discontinuance of the traffic within the Bocca Tigris, why can you not also put an end to it in the outer waters beyond the Bogue?"

As it seems scarcely possible to avoid all direct allusion to the difficult question of the traffic in opium, I shall take this opportunity of saying a few words upon this important subject.A detailed account of its remarkable history, and of the vicissitudes which attended it, both within and without the Chinese empire, would afford matter of the greatest interest, but could hardly find a place in this work.

In former times, as is well known, opium was admitted into China as a drug, upon payment of duty; and, even the prohibition which was ultimately laid upon it, was regarded by the Chinese themselves as a mere dead letter.Indeed, precisely in proportion to the difficulty of obtaining the drug, did the longing for it increase.

The great events which sprang out of this appetite of a whole nation for "forbidden fruit," on the one hand, and of the temptations held out to foreigners to furnish it to them, on the other, may be considered as one of those momentous crises in a nation's history, which seem almost pre-ordained, as stages or epochs to mark the world's progress.

It is curious enough, that, at the very time when a mercantile crisis was growing up at Canton, a political intrigue, or, as it might be called, a cabinet crisis, was breaking out at Pekin. In fact, strange as it may appear, it is believed in China, upon tolerably good authority, that there was actually a reform party struggling to shew its head at Pekin, and, that the question of more extended intercourse with foreigners, was quite as warmly discussed as that of the prohibition of the import of opium, or of the export of silver.

Memorials were presented to the emperor on both sides of the question; and his Majesty Taou-kwang, being old, and personally of feeble character, halted for a time "between two opinions," alternately yielding both to the one and to the other, until he at length settled down into his old bigotry against change, and felt all the native prejudices of a true son of Han, revive more strongly than ever within his bosom.

But the question of the Opium-trade, or Opium laws, which for some time had been almost a party matter, like the corn laws in our own country, became at length a question of interest and importance to the whole nation, and was magnified in its relations by the very discussion of the points which it involved.

It is said that the head of the reform party (if it can so be called) in China was a Tartar lady, belonging to the emperor's court, remarkable for her abilities no less than her personal attractions, and possessed of certain very strong points of character, which made her as much feared by some as she was loved by others.She was soon raised even to the throne itself, as the emperor's wife, but lived only a few years to enjoy her power.Her influence soon came to be felt throughout the whole of that vast empire; it was the means of rewarding talent, and of detecting inability.She seemed to possess, in a marked degree, that intuitive discernment which sometimes bursts upon the female mind as if by inspiration.The tone and energy of her character were in advance of her age and of her country.She had many grateful friends, but she had raised up for herself many bitter enemies; party feeling ran high, and became at length too powerful even for an empress.

Gradually her influence diminished, the favour of the emperor declined, her opponent again got the upper hand, and at length she pined away under the effects of disappointment, and perhaps injustice, and died. But her influence, so long as it lasted, was unbounded, and was felt through every province.

Her principal adherents and dependents naturally lost their power when that of their mistress was gone. The question of more extended trade with foreigners was now again set aside; the old feelings of bigotry and national pride resumed even more than their former vigour. Opium at once became the instrument, but ostensibly PATRIOTISM became the groundwork of their measures. The old national feeling against foreigners throughout the empire was revived; and in the midst of it all, as if ordained to hasten on the momentous crisis which waited for its fulfilment, the son of the emperor himself died in his very palace, from the effects of the excessive use of opium.