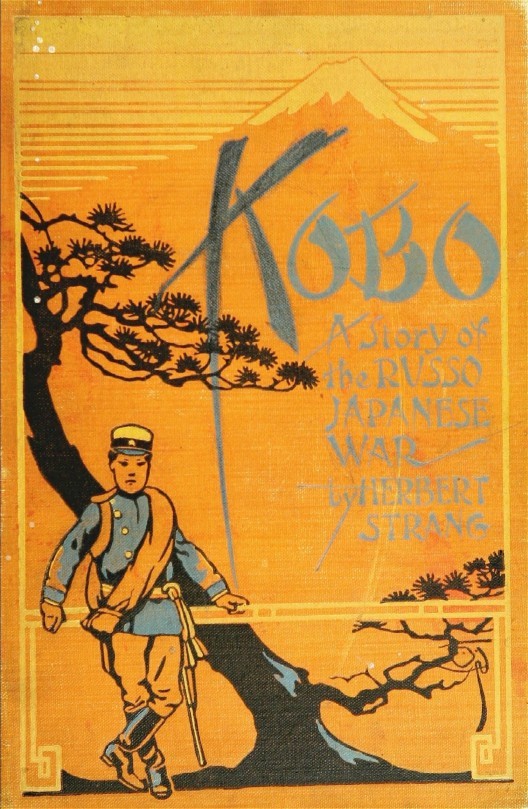

Kobo: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War

Play Sample

CHAPTER VII

The Battle of the Destroyers

A Chance for the Destroyers—Flotillas in Action—Winged—Repairing Damages—To the Yalu

Yamaguchi's business in Seoul being completed, he lost no time in returning to Chemulpo. In default of other instructions, he decided to keep Bob with him, and half an hour after his arrival, the Kasumi steamed out of the harbour to rejoin the fleet. Its fringe came into sight some ninety miles south-east of the Liau-ti-shan promontory. Through his glass Bob saw a destroyer detach itself from the squadron and come rapidly towards the Kasumi

"Coming to make sure who we are," remarked Yamaguchi.

When the identity of the new-comer had been satisfactorily established, the other boat ran up signals, from which Yamaguchi learnt the position of the main fleet. Two hours later the Kasumi, going at half-speed, sighted the cruiser squadron, and about five miles beyond them the forest of military tops belonging to the Japanese battle-ships. Running close up to the Mikasa, Yamaguchi went off in a boat to make his report to Admiral Togo, and returned in high feather at having been ordered to place himself at the disposal of Captain Asai, who was in command of three destroyers that formed the first division of the Japanese torpedo flotilla.

"What about me?"asked Bob.

"Not a word.The fact is, I forgot all about you.I didn't mention you, neither did the admiral."

"Out of sight out of mind," remarked Bob."But I'm delighted to hear it, for now that I'm used to this cockle-shell's little eccentricities I'm perfectly at home.Is there any chance of your going into action?"

"Every chance, I should think.I fancy we're going to have another slap at the enemy."

"The whole fleet, you mean?"

"No I don't.I've an idea the admiral wants to see how we mosquitoes can sting.Feel jumpy?"

"Not in the slightest.There's nothing I'm more anxious to see."

"Well, it may be pluck, but I call it sheer ignorance.Here we are in mid-ocean, a mere egg-shell—you know that; but we've enough explosives in our magazines to send half London sky-high, and a single fortunate shot plumping into us would separate us all into our elementary atoms."

The desired order came sooner than was expected. Late in the afternoon of Wednesday, March 9, Admiral Togo signalled two divisions of destroyers to approach Port Arthur, the one division to watch the entrance while the other laid mines at various points along the coast. The former duty was allotted to Captain Asai's division. Darkness had fallen, and the sea was rolling high, when the two flotillas, followed at a considerable distance by a couple of cruisers, broke off from the rest of the fleet and steamed northwards towards Port Arthur. On the Kasumi there was none of the orderly bustle of clearing for action that Bob had observed on the MikasaA destroyer must always be ready.The ward-room and the warrant officer's mess were fitted up as hospitals for wounded; the trolley for bringing torpedoes from the magazine under the turtle-back deck to the tubes aft was tested along the rails; Yamaguchi had a short colloquy with the engineer; and then he went to his place on the fore-bridge, confident that all was right.

The flotilla opened up the lights of the port about midnight.The presence of the boats was soon discovered by Russian scouts, for at irregular intervals the guns of the forts tried long-range shots at them.Within a few miles of the port the divisions separated, the second steaming straight for the harbour, where it proceeded to lay mines from the mouth of the channel along the coast towards Dalny.Captain Asai's three vessels meanwhile cruised off the Liau-ti-shan promontory.

Bob remained all night with Yamaguchi on the bridge, finding it less chilly there than below. In spite of the blazing furnaces he had never felt cold so keenly as in the captain's cabin when he dived down the small circular hatchway to fetch Yamaguchi an extra jacket. At about three o'clock in the morning they began to run down the coast. There was a head sea, which broke in great masses over the fore-deck, the driving spray being carried high over the canvas screens surrounding the bridge. Dawn was just breaking when the look-out descried the low hulls of several destroyers far-off on the horizon. The intelligence was at once signalled to Captain Asai on the AkatsukiFrom his bridge he soon discovered that the approaching vessels were six in number; obviously they could not belong to the Japanese squadron.The order was instantly given to attack.Everything was already prepared for immediate action; every man was at his post; and the three vessels, cutting at the rate of an express train through the heavy seas, bore straight down on the six Russian destroyers.

"It's long odds on the Russians," remarked Bob to Yamaguchi.

The Japanese shrugged."They're not islanders," he said; "we're like you Britishers, sea-dogs from birth, and our seamanship is a trifle better than theirs, I fancy.Besides, we're probably better armed.A Russian destroyer only has three-pounder quick-firers besides its twelve-pounders.Their shots can pierce our egg-shell, of course, but our six-pounder shots will do far more damage to their interiors."

"Won't you use your torpedoes, then?"

"No.Dog doesn't eat dog: we keep our torpedoes for larger game."

"You are not using the conning-tower?"asked Bob, noticing that Yamaguchi showed no sign of leaving the bridge.

"No; it is better to take one's risk in the open.Those peep-holes are rather worrying when you want to have a good look at the enemy."

The three vessels were now in line ahead—steaming straight for the Russian flotilla, the Akatsuki leading, the Kasumi a quarter of a mile behind, and the Asashio making a good third at the same distance. Bob on the fore-bridge was tingling with exhilaration. All his faculties seemed to be braced up. He had no sense of danger, in spite of his knowledge that one lucky shot from the Russians might explode the magazine beneath him and destroy the ship and every soul on board. His strongest feeling was one of impatience. The vessel was bounding along at more than race-horse speed; yet it appeared to be going slowly, too slowly, and he felt he would have liked to cry "Hurry up! hurry up! faster! faster!"

Two minutes had passed since the order "Full speed ahead!" Then from the fore-bridge of the Akatsuki the six-pounder shrieked. From that moment Bob saw and heard nothing except what went on in his own vessel. Immediately after the Akatsuki had opened fire, Yamaguchi gave his first order. There was an ear-splitting report; the vessel seemed almost to pause momentarily in its career, like a racer pulled up on its haunches; and a second or two later Bob saw a cloud of smoke over the fore-deck of the leading Russian boat, which, travelling at thirty knots, instantly shook off the pall and emerged from it with one funnel completely shattered. Bob did not hear the explosion of the shell; the din from the Kasumi and the other Japanese vessels, and from the approaching Russians, was too great to allow individual sounds, except within a few feet, to be distinguished. Almost before he was aware of it, the two flotillas had met and passed; they were within a few yards of each other, so near that the faces of the Russian seamen were easily visible; but Bob afterwards remembered few details, for the actual time of transit could be measured by seconds. The vessels sped past at a combined speed of some sixty miles an hour.

As the Kasumi came abreast of the leading Russian boat, which had already received a battering from the Akatsuki, her twelve-pounder added a growling bass to the whining of the lighter guns, now firing at their maximum speed. At this moment a shot from a three-pounder struck the compass-box on the fore-bridge, just above the chart-room, and a few feet from where Bob was standing. A splinter from the bursting shell hit the gunner serving the six-pounder on the bridge; the man was killed in an instant; a comrade came imperturbably to take his place. Immediately afterwards a twelve-pounder shell carried away the ventilator of the aft stokehold, and a three-pounder, penetrating the hull as though it were of paper, exploded in the ward-room, severely injuring a man waiting there to receive the wounded. Then the rearmost vessels of the two squadrons passed, and the Kasumi's twelve-pounder astern got in a parting shell, which took effect apparently among the boilers of the Russian, for when the smoke from the bursting charge had cleared away, the vessel was seen to be enveloped in a vast cloud of steam. Bob was surprised at the small total effect of such vigorous firing on both sides, though he realized afterwards that at the rate at which the vessels were steaming it was still more surprising that the effect was so great as it was.

But the fight was not yet over. At a signal from the Akatsuki the Japanese vessels spun round almost within their own length, and started in pursuit of the enemy, now steaming at half-speed to cover the retreat of the damaged boat. The Russian flotilla was somewhat bunched; presumably the boats had been hard hit, and either their commander had no definite plan of action, or their mechanism had been so much damaged as to retard their movements. Two had turned, but three others were manoeuvring in a small space, hampering one another, while the sixth, the lame duck, was making the best of its solitary way in the direction of Port Arthur. Captain Asai was quick to seize his opportunity. Slightly altering his course so as to cut obliquely across the path of the Russians, he brought the whole of his port-side guns to bear upon the huddled enemy; then before the Russians had time to take advantage of the broad target offered to them, he reverted to the line-ahead formation, and bore straight down upon them.

This time the two flotillas passed at such close quarters that a man could have thrown a line from one ship to the deck of its opponent. They were moving at less speed than in the former encounter, and the effects of their mutual bombardment were correspondingly greater. For the first time Bob was conscious of a tremor, not of personal fear, but a reflex of the wild scene around. It seemed to him as if nothing could survive the hail of shells that screamed and whistled through the air, to burst with ear-splitting crash whenever one was fortunate enough to find its billet in the hull or upper works of the gallant KasumiOne shell, apparently from a three-pounder, ricochetted off the turtle-back deck beneath the forebridge, and burst in the air about ten yards to starboard, the splinters breaking a hole in the aftermost funnel and knocking a corner off the compass-box that stood within a few feet of it.

"There goes our second compass.We have only the standard left," said Yamaguchi.

Almost at the same moment there was a crash just below the spot where Bob was standing.A twelve-pounder shell had passed clean through the chart-room without exploding.

"A narrow squeak!"said Bob.

"Yes; we'll give that fourth Russian a little pepper," replied Yamaguchi, his face lit with the joy of service.

He gave an order, and all the Kasumi's port six-pounders let fly at the Russian destroyer, several shells ploughing into her hull just above the water-line. Bob noticed the strained expression on the faces of the Russian seamen, and one vivid picture flashed upon his retina and was gone—the picture of a man, struck by a fragment of a Japanese shell, falling with outstretched arms across his gun. A few seconds more and the Kasumi again came abreast of the last vessel in the Russian line. She replied so feebly to Yamaguchi's skilfully-aimed broadside that it was evident she had already been severely handled by the Asashio, now leading. But as the vessels passed, a big Russian picked up a tin canister and hurled it with such good aim at the Kasumi that it fell on the platform of the fore-bridge between Yamaguchi and Bob. The latter instantly lifted it to throw into the sea, but Yamaguchi stayed his hand.

"There's no danger," he said; "it will not explode now.We'll keep it; I'll make you a present of it."

At that instant a three-pounder shell exploded in the aft stoke-hold, bursting a steam-pipe, and dangerously wounding one of the engineers.

"Poor Minamisawa!"said Yamaguchi, when he heard of it."He was twice commended for gallantry during the attack on Port Arthur a month ago."

By this time the flotillas had again passed each other.But on turning once more to renew the fight, Captain Asai found that the enemy had had enough of it.They were steaming full speed ahead towards the harbour.The order was given to pursue; but the Russians had obtained too great a start to permit of their being overhauled before gaining the protection of their cruisers and shore batteries.The pursuit had necessarily to be abandoned, and the Japanese commanders turned their attention to making good the damage sustained during the action.

The full results of this spirited forty minutes' engagement were not known on board the Kasumi until some time afterwards. Near the entrance to the harbour two of the Russian destroyers were intercepted by the second Japanese flotilla. The Russians, battered as they had been, showed no lack of courage. There was a short, sharp fight, during which one of the boats slipped past the enemy and got away. The second, however, the Stereguschitshi, was not so fortunate. She fell a prey to a Japanese destroyer, and was taken in tow. But she was leaking badly; the tow-rope was snapped like a thread of cotton by a heavy sea, and, left to her fate, the Stereguschitshi went down.

Meanwhile the three vessels of Captain Asai's division lay for about an hour with only steering-way on, until the extent of their injuries should have been ascertained and as far as possible repaired. On the Kasumi two compass-boxes had been damaged, part of the fore-bridge carried away, one funnel breached, the chart-room almost entirely wrecked; but the most serious injury was the shattering of the steam-pipe, throwing one engine out of action. The other two vessels stood by while some repairs were being made; it was not safe to leave the Kasumi to face alone the risk of the appearance of the Russian cruiser squadron. The work was barely completed, indeed, when two cruisers, the Bayan and the Novik, the latter flying Admiral Makaroff's flag, steamed out of Port Arthur and ran down towards the three destroyers.But at the same moment a forest of military masts appeared on the horizon: the Japanese fleet was evidently coming up in support; and the two Russians, fearful of being cut off, retired, fighting at long range with the leading Japanese cruisers until they ran in under shelter of the forts.

"Another bombardment coming off?"said Bob to Yamaguchi, as the splendid battle-ships went by.

"Perhaps.The flagship is signalling us."

"What are the signals?"

"Nothing important; the admiral merely says he is satisfied with us."

The flush of pleasure was not on Yamaguchi's cheeks, but on Bob's. He remembered the historic "Well done, Condor!"and felt a sympathetic glow.

The battle-ships steamed past, and took up a position whence they could neither see the Russian vessels nor be seen by them.Depending on high-angle fire from their twelve-inch guns, they sent shell after shell into the town and harbour, the effect of their shots being signalled by wireless telegraphy from the cruiser squadron stationed round the point.The bombardment lasted for nearly four hours, during which several outbreaks of fire were seen in the town, and a distant explosion announced that a magazine had been blown up.There was but little reply from the Russians, and about two o'clock Admiral Togo, having accomplished his immediate purpose, retired, accompanied by the cruiser and destroyer squadrons.

Two hours later Yamaguchi was signalled to go aboard the flagship. It was blowing hard at the time, and seas were sweeping the deck of the Kasumi, tossing her about, and rendering the launching of her boat a matter of no little difficulty. By the time the little lieutenant reached the Mikasa he must have been drenched through and through.

"Well," said Bob, when he returned, "are you promoted again?"

"No; but you are."

"What do you mean?"

"The admiral has remembered you, that's all. This morning, being forgotten, you were at zero; you may be soon at boiling-point. I am to put you on board the Yoshino—if I can."

"Ugh!it won't be a dry passage.If you can, you say?"

"Yes; I am ordered to the mouth of the Yalu, and shall drop you on the way, if I can do so without losing time."

"In a hurry, then?"

But Yamaguchi made no reply. He was telephoning to the engine-room. In a few minutes the Kasumi was slugging through the sea, half-speed ahead, in a north-easterly direction. The wind increased to half a gale; huge seas broke continually with thud and swish over the vessel, and Bob did not relish the prospect of the swamping he must undergo if he were to reach the Yoshino's side. He was overjoyed when he saw that the distance between the destroyer and the cruiser squadron was increasing instead of diminishing. Yamaguchi had clearly given up the idea of putting him aboard the Yoshino. From his manner Bob had already guessed that the expedition on which he was now speeding was one of some importance, and when at length the lieutenant turned to him and said, laconically, "Can't waste time over you", his pulse leapt at the thought that he was still to remain on the Kasumi and share in whatever adventure there might be in store.

CHAPTER VIII

Cut Off

Secret Service—Yamaguchi Returns—A Quick Change—A Bleak Ride—On the Trail

For some time Yamaguchi was too intently occupied in navigating the vessel between the Elliott and the Blonde islands to concern himself with Bob.But when he was through the strait he left the bridge and went below to get something to eat.Then for the first time he told Bob what his mission was.He had been ordered to survey the coast-line of Korea Bay as far as the Yalu, to report on the state of the ice, and especially to examine the condition of things at the mouth of the river.If he could at the same time pick up any information as to the disposition of the Russian forces along the shore, so much the better; but though he might run any personal hazards, he was on no account to risk his vessel; in war time destroyers cannot easily be replaced.

"You're fixed up for ten days, you see," he said to Bob."I'm to be back in that time, and you're bound to remain with me."

"You'll have to go ashore, I suppose," said Bob.

"Yes, if I can get through the ice.And I think I can.I've been this way before; I suppose that's why the admiral selected me for the job.Unless it's because one of our engines is out of action.The ice usually clings to the shore till some time after this, but just before we reach Taku-shan there's a spit of land where, by some movement of the currents, the ice is sometimes loosened; and if I'm lucky, there'll be passage-way for a boat, if not for the destroyer herself."

"I say, you'll let me go with you."

"Certainly not. I'm already one notch down through not being able to put you on the Yoshino, and I can't afford to report you gone for good."

"But why shouldn't I go where you go?"

"Well, for one thing, it's my job and not yours.The admiral has plenty of lieutenants, but only one Bob Fawcett!Besides, why take you into danger?If the Russians catch me, I'm shot.Well, that's part of my work; but you—you'd be shot too, and an Englishman is worth—how many of any other nation?"

"Too many to count," said Bob smiling.

"Anyhow, you're twice as heavy as me, and nearly twice as tall; and another thing, you'd find it hard to pass for a Chinaman."

"Oh!you're going in for disguises, then."

"Yes, I shall stick on a pigtail; I won't be caught if I can help it."

"D'you know, I've an idea.Your mention of a disguise makes me wonder if that Chinaman I saw in Seoul wasn't a Chinaman after all.I saw him before at Sasebo with another fellow; there was something about them I seemed to know.D'you think they were really Japanese I had caught sight of in Tokio?"

"It's possible, of course; but I shouldn't jump to conclusions.Their disguise must have been pretty feeble if you saw through it after only a casual glimpse in Tokio."

"Ah!I've a good memory for faces.But let us go on deck, it's so horribly cold down here."

By this time the vessel had left the Elliott Islands some ten knots on her port quarter.Looking out in that direction, Bob drew Yamaguchi's attention to the masts of several vessels that stood up among the islands.The lieutenant smiled, but said nothing.Bob, in spite of himself somewhat annoyed at his friend's reticence, formed his own conclusion: the ships were probably transports landing men or supplies on the islands, or preparing the way for a Japanese army-corps in anticipation of a siege of Port Arthur.

Keeping well out in the bay, the Kasumi thrashed her way through a head-sea on a course north-east by east. Darkness came on, and loth though he was to go below and shiver, Bob at length was so tired that he had to turn in. He spent a by no means comfortable night. It was like sleeping under a blanket of ice. During the hours of darkness, in order to save coal, the Kasumi went at less than half-speed, and it was nearing dawn when she arrived off Taku-shan. All that day Yamaguchi kept her far out, so that she should not be seen from the shore, which was fringed with ice. The wind had dropped, leaving only a long swell on the waters of the bay. At nightfall the Kasumi ran in, careful soundings being taken at various points; and Yamaguchi found, as he had hoped, that the current had kept open a narrow waterway between Takushan and the island of Talu. Announcing his decision to go ashore, he went to the ward-room, and soon returned, transformed into a very presentable young Chinaman, drooping moustache, skull-cap, pigtail, and all. A boat was lowered, and the lieutenant departed, saying that he would probably return by daylight.

That was the first of several short expeditions Yamaguchi made at night to the shore. Bob could never induce him to speak of what he did, but noticed that he always appeared abundantly satisfied. On all these occasions the same plan was followed: Yamaguchi was rowed in the darkness as near to the shore as the ice-fringe allowed; he finished the distance on the ice; and the boat returned to the Kasumi until just before dawn, when it again went shorewards and brought him off.

Four days thus passed away, and on the evening of the fourth, when the Kasumi had come opposite the mouth of the Yalu, Yamaguchi told Bob that he was now going on the last of these night journeys, and hoped, on his return, to rejoin the fleet and make his report to Admiral Togo.

"I may be away longer this time," he said.

"Can't I go?Every time you have been away I have been in a perfect stew lest you shouldn't come back, and I find it all precious slow."

"Very sorry, but it's impossible."

"How long do you expect to be away this time?"

"I can't say, but I have three days' rice stowed away in my pockets.I hope I shall not be so long as that.You had better amuse yourself by playing 'go'."

"But what if the Russian fleet comes up while you're away?For my part, I don't understand a commander leaving his vessel like this."

"You are not the admiral, you see.I don't think you need trouble about the Russians.The Port Arthur fleet daren't come, and the Vladivostock one probably can't.Good-bye."

Two days passed away, and by the end of the second Bob was almost tired of his life; he had played "go" till he went nearly mad. He wandered all over the vessel, examining for the tenth time every nook and cranny of it, until he felt that he could have drawn plans of its construction from memory. He got one of the gunners who knew something of English to teach him a little Japanese—common phrases like Nodo ga kawakimashita, "I am thirsty", which to a Japanese is "throat has dried"; and "I am hungry"—O naka ga sukimashita, "honourable inside has become empty"; and "it is horribly cold"—O samu gozaimasu, "honourably cold augustly is", until he wondered whether it would be correct Japanese to say "I'll augustly punch your honourable head".But even such amusement as this palled; and to his own restlessness was presently added anxiety about Yamaguchi, for whom he felt sincere affection.At sundown on both evenings the boat went off towards the shore in accordance with the captain's instructions, but on both occasions it returned without him.On the third evening, Bob decided to accompany the boat.The sky was clearer than it had been for many nights past; the moon was rising, and whatever danger there had previously been of the boat being seen from the shore was now more than doubled.Bob felt anxious, and, as he sat in the bows, peered through his glass towards the snow-covered flats and low hills that stretch on either side of the Yalu estuary.

The sailors pulled in to the verge of the ice, then lay on their oars.Many minutes passed.The crew waited in silence, and as the moon rose higher and its rays were reflected from the snow, it became almost as light as day.The sea heavily lapped the sides of the boat and swished against the jagged edges of the ice; otherwise there was no sound.

Suddenly, against the white background, a small dark form was seen, apparently rising from the other side of a hillock whose contour was indistinguishable in the universal white.The object soon defined itself as a small man running, and at headlong pace.Bob stood up in some excitement, wondering whether this was Yamaguchi at last.Immediately afterwards he saw other forms appear upon the crest, and he drew in his breath sharply as he recognized that these were men on horseback.They came rapidly over the hillock, and began to descend towards the sea after the running figure.Bob raised his glass to his eyes; yes, the runner was Yamaguchi, and the horsemen wore the fur caps and carried the long lances of Cossacks.It was a race for life!

The hillock was nearly half a mile away.Between it and the boat lay an almost level stretch of mud flats, covered for many inches by recently-fallen snow, and fifty yards of ice, now of course indistinguishable from the land.Could Yamaguchi reach the boat in time?He had the start of his pursuers, but they were mounted, and, as Bob now saw, there were eight of them.It was almost impossible that the runner could escape.Yet it seemed impossible to help him.The seamen in the boat had rifles, but now that pursuers and pursued had descended the declivity and come to the flat, a shot, however well aimed, might hit the man it was intended to assist.

In one tense moment Bob seemed to live a lifetime.Then, with a cry to the men to remain where they were—which, not knowing English, they understood rather by the tone than by the words—he sprang over the side of the boat on to the ridge of ice.It creaked and sank under him, but he leapt on towards the shore, intent on assisting the flagging footsteps of the Japanese, who was evidently near the end of his endurance.The ice crackled and groaned as Bob raced on.He reached the softer snow, and his pace was checked; he heard a shot from one of the pursuing Cossacks ring past his ear; he shouted a word of encouragement to the panting lieutenant, and then, leaping, floundering, staggering over the intervening yards, he caught Yamaguchi by the arm and turned to run with him towards the boat, feeling all the time that theirs was a hopeless case, for the foremost horseman, distancing his comrades, was now but a dozen yards away.

All at once a shot flashed from the boat.Bob heard a strange sobbing sigh behind him.A moment after he felt the impact of a heavy body, he was thrown violently on his face, and a riderless horse galloped madly on towards the sea.

Bob lay for a few moments dazed on the snow.The cold brought him to his senses.He heard several shots ring out, and lifting his head cautiously he saw four Cossacks galloping on to the ice, and three standing by the side of their horses, taking aim at the boat across their saddles.Then came the crack of ice beneath the horses' hoofs; loud cries of distress rose on the air as men and horses floundered in the water; and a fusillade continued between the dismounted Cossacks on the shore and the crew of the boat, which was now being rapidly pulled out to sea.Bob saw his opportunity; it might last but a moment, he had no time to lose.Rising to his feet, still dizzy from the blow, he saw a few feet behind him the outstretched body of the dead Cossack; his horse had returned and was now standing patiently by his side.He stooped down, quickly relieved the Cossack of his cap, cloak, and arms; then, going quietly to the animal, he sprang upon its back, saw at a side-glance that the surviving Cossacks were still occupied, and touching the horse with his heel, trotted away southward on a line parallel with the coast, towards a clump of trees looming black against the moonlit sky more than half a mile away.

Having arrived there, and being out of sight from the scene of his late adventure, he pulled up to consider his position. Yamaguchi, he hoped, was by this time well on his way to the Kasumi; if only he himself could remain in hiding until the morning, and the vessel were still lying off the mouth of the river, it might be possible then to get on board.All depended on whether the Cossacks who had survived the fray would notice his disappearance, and the fact that their dead comrade had been despoiled.That they would not do so was in both cases very unlikely.His only chance, therefore, would be to make his way southward, in the hope of coming upon the outposts of one of the Japanese forces which he knew had been landed in the country.That course would be attended with considerable danger.News of the recent incident was bound to bring a larger force of Cossacks upon the scene; parties of Russians would soon be scouring the country, not only to discover traces of the fugitive, but to keep an eye open for the torpedo boat destroyer.It was well-known on the Japanese fleet that Cossacks were employed to ride up and down the coast and signal the approach of hostile vessels, and these would scarcely fail to note and follow up the tracks of his horse in the snow.

"This is a precious fix to be in," he thought; and the more he reflected the more awkward his position appeared. The chance of getting in touch with the Kasumi was very remote, for if he emerged from hiding and went down to the shore he could scarcely hope to escape discovery by Russian patrols. On the other hand, if he hid during the day he would not be seen from the destroyer. Besides, the Kasumi was due to rejoin the fleet; and though he knew that Yamaguchi, if a free agent, would do anything to serve him, he knew also that, with a Japanese, duty came inexorably first, and it was vain to expect Yamaguchi to cruise about indefinitely on the chance of picking him up. Supposing he left hiding and rode towards the south, there seemed little likelihood of his reaching the Japanese lines. Their outposts were probably not less than a hundred miles away. Between them and him many detached parties of Russians were no doubt patrolling the country. Even if he escaped the Russians he might fall into the hands of the Koreans, and that would perhaps prove a case of out of the frying-pan into the fire. Much as the Koreans hated the Japanese, by all accounts they hated the Russians still more; and being mounted on a Cossack's horse, and wearing Cossack uniform, knowing, moreover, nothing of the Korean language, he would have short shrift if he stumbled among the natives. Yet another consideration. Both he and his horse must have food. A bundle of hay was tied to the latter, sufficient perhaps for one feed; and on rummaging in the saddle-bags he found a little black rye bread and a flask of vodka. But this was very precarious sustenance, and he would be forced under stress of hunger to enter a village within twenty-four hours at the latest.

Of all the dangers besetting him the prospect of being followed up by the Cossacks of Yongampo was the most immediate, and Bob shut his eyes to the other contingencies in order to provide against this.Obviously the farther he got from the scene of the fight the better.He rode carefully through the clump of bare trees southward, and, emerging into the open, set his horse at a sharp trot.The ground was covered with snow to a depth of several feet, and as the horse's feet sank into it slightly, he concluded that the frost was yielding.Guiding himself by the sound of the waves lapping against the ice on the shore, which creaked and groaned, and now and again broke with a sharp report, he struck along the coast in the direction, as he believed, of Seng-cheng.The Cossack's deep saddle was very comfortable, but he wished that the stirrups were lower: his knees were a good deal nearer his nose than he was accustomed to.

The moon was going down, but there was still sufficient light to show that, except for a few scattered clumps of wood, the country was very open, and he knew that in the daytime he could be seen for miles.As he rode, he therefore looked eagerly about in search of some hiding-place where he might spend the rest of the night in tolerable security.After some three or four miles he found that the country was becoming increasingly difficult.On his left the irregular hills rose more and more steeply, and he was forced more and more towards the ice.Warned by his recent experience of the Cossacks, he edged away until he reached at length the summit of a slope some distance above the sea.Great banks of cloud were looming up across the sea; the wind was rising, and the air had that incisive rawness that portends snow.To be caught in a snowstorm in this bleak latitude would be a calamity, and Bob looked more anxiously around for shelter.

Some distance above him he saw, outlined against a clear patch of sky not yet reached by the clouds, a large dark building, which from its size he thought must be a place of some importance.It was in shape unlike anything he had previously seen.As he looked towards it, he caught sight of the last horn of the moon apparently in the very centre of the building.Evidently the place was a ruin.Whatever hesitation Bob might have had in approaching an inhabited dwelling-house disappeared; he made his way towards it with some difficulty, the horse floundering through drifts which more than once threatened to engulf him.Arriving at the building, Bob found that it was the ruin of a large stone pagoda, probably at one time part of a monastery.The wind howled eerily through its dilapidated walls, but it provided shelter of a sort; and, what was more important, being situated on a slight eminence it would give him a good outlook in the morning, not only far across the sea, but also landward towards the mouth of the Yalu.In this lonely place, then, Bob determined to pass the remainder of the night.

His first care was to rub down his horse; then he gave it half the bundle of hay.Then he unstrapped one of the blankets from the saddle and proceeded to make himself as comfortable as possible.He swallowed a few mouthfuls of the bitter bread, took one sip (more than sufficient) of the burning vodka, and being tired out soon dropped into an uneasy sleep, from which, with the instinct of one accustomed to early rising, he awoke at the first pale glint of dawn.Rising stiffly to his feet, he again fed the horse, ate a little bread, and went outside to look round.

Northwards, in the direction from which he had come the previous night, he could see with the naked eye for several miles across the snow; and through his glass, which he had luckily brought with him, he descried what was evidently a small town—no doubt Yongampo. Over the whole white stretch intervening there was no sign of life. Looking then seaward, he saw a leaden sky, white-crested waves lashed by the high wind and breaking in angry foam on the ice—nothing more. There was not a speck on the sea. The Kasumi had left him to his fate.

"And I dare say Yamaguchi is even more sorry than I am," he thought.

Then he turned again to the land and swept the horizon with his glass.What is that?In the far distance, towards Yongampo, he discerns two dark specks.He gazes intently, his hands so numbed with cold that he can scarcely hold the glass steadily.The specks are growing larger.Both are approaching him, one coming southward in a straight line, the other making a trend somewhat to his right.For some minutes he gazes at them; the specks become masses, and gradually define themselves as bodies of horsemen.Doubtless they are Cossacks; it is time to be up and away.

CHAPTER IX

Chased by Cossacks

A View-Halloo—Cossacks at Fault—Bluff—Suspicious Hospitality—On the Pekin Road—A Hill Tiger

The situation was desperate.One band of Cossacks was evidently following the tracks of his horse, the other taking a short cut to head him off.The Mandarin road from Pekin to Seoul could not be far away; the Russians had probably assumed that he would ride in that direction, and acquainted as they no doubt were with the neighbourhood, they would have a great advantage over him.His only hope lay in his horse, which was fortunately a good one, and in the pink of condition.He must ride, and ride, and ride.

Returning to the pagoda, he found that the horse had eaten the last wisp of hay.He led it out, down the slope on the side farthest from the pursuers, through a dip between two low hills; then coasting round a somewhat steeper hill which hid the pagoda from sight, he judged it safe to mount, and was soon cantering over the snow-covered ground.It was rolling country; at one minute he was as it were on the crest of a wave, the next he would be in a trough.The snow was soft, and the horse's hoofs left deep pits in the yielding surface by which the course of his flight could be easily tracked.Soon he lost sight of the sea, and had nothing by which to take his bearings; the sky all around was one unbroken lead-gray.As he rode on, he saw with misgiving that the hills were becoming lower and lower; he would be in full sight of the Cossacks when they reached the heights he had just left.There was no alternative but to push on.Of refuge there was none; the whole country seemed to be desert, with no marks of human habitation except here and there a native hut perched on the edge of a clump of trees, the abandoned home of some wood-cutter.

Every now and then he reined up his horse and turned in the saddle to see if his pursuers were in sight.Struggling up a long slope, and halting at the top to breathe the animal, he saw before him an almost level stretch, and behind him—yes, there they were at last, a band of at least twenty, who had probably dodged round some of the hills which he had laboriously climbed.He looked eagerly round; there was no way of eluding the pursuers.Should he set his steed at the gallop and try to distance them?That was a vain hope; it would exhaust his panting horse, and the Cossacks would wear him down, following untiringly upon his track like wolves.He must on again, and husband the animal's strength as much as possible.

Down the slope, then, he rode, the horse's breath leaving a trail of vapour in the cold air.The sky was growing blacker, the wind, which had been blowing in gusts, dropped; there was no sound but the soft glugging of the hoofs as they plunged into the snow.Suddenly Bob heard a faint shout behind him.He knew well what it meant; the Cossacks had reached the crest of the hill and seen him cantering before them.He looked over his shoulder; they were no more than a mile distant.In half an hour they would close in upon him; perhaps the second band had already come round upon his flank and was now ahead of him; for all he knew, he might have been riding in a circle.Still he must ride on.He quickened his horse's pace; some ten minutes later he heard the distant crack of shots, but as no ping of the bullets followed he guessed that they had flown wide.But the fact that the Cossacks were firing was ominous.They were accustomed to take flying shots from the backs of their steeds; at any moment a luckily-aimed bullet might hit him.He lay upon the horse's neck and called upon the beast to gallop.More shots, more shouts pursued him, but the sounds were fainter.The gap between him and the Cossacks must be widening; could the advantage be maintained?

He spoke encouragingly to the animal, which galloped along with wonderful sure-footedness.Suddenly Bob felt a damp, cold dab upon his brow, then another; he lifted his head, and gave a quick gasp of relief when he saw that snow was falling.The lowering sky had opened at last; in a few moments the rider was making his way through a dense shower of whirling snowflakes, which filled eyes and ears and shut out all objects beyond a hundred yards.By favour of this white screen he might yet escape.

To the left he saw a small dark clump of trees stretching up the hillside.Pushing on until he came level with the furthermost edge he wheeled round, struck through the fringe of the clump where the trees were thin, and ascended the hill at right angles to his former course, in hope that his pursuers, losing him from sight, might overshoot the spot where he diverged before they discovered their mistake.The blinding fall of snow must now be fast obliterating his tracks; to distinguish them the Russians would have to slacken speed; and the few minutes he thus gained might enable him to escape them altogether.But he dared not wait; the Cossacks, finding that they failed to overtake him, would soon cast back and probably scatter in the direction they would guess him to have taken, and how could he expect to elude them all?Walking his horse for a few minutes to allow it to recover breath, he again urged it on, hoping that his luck would yet serve.

The air was still thick with the falling snow; to follow a certain course was impossible.He rode on.Suddenly he heard a dull thud not far to his right; could it be the sound of the Cossacks returning already?Quick as thought he reined up behind a large tree, and peering round the trunk saw, through the whirling flakes, a number of shadowy forms flit past in the opposite direction to that in which he had been going.Mingled with the thudding hoofs came the muffled sound of voices.He could not distinguish the riders, yet he felt sure that they were his pursuers.Waiting till all sounds were quenched, he cantered slowly ahead, knowing now that could he but keep a straight course the Cossacks would be unable, while the snowfall lasted, to find his trail.But for an accident he was safe.

Safe, indeed, from the pursuers; but there were still dire perils to face.He had been riding hard for three hours; the horse had for some time been showing signs of fatigue; he had no food either for it or for himself, and he was himself ravenously hungry.He was in a wild, desolate, sparsely-populated region; should he encounter natives he would be taken for a Russian; he could not speak their language; even if his horse's strength held out until he reached an advanced Japanese outpost, he might be shot before he could make himself understood.Yet, unless he fell in with someone who would give him shelter and food, he and his horse alike must succumb to fatigue and cold, and he would have escaped the Scylla of Russian hands only to meet death from the Charybdis of the elements.Chilled, tired, hungry as he was, for a brief moment his mind was crossed by the shadow of despair; but he pulled himself together, shook the reins, straightened himself, and once more rode on.

It seemed to him that he was wandering on a vast white Sahara, or adrift on a wide sea without chart or compass.All at once, on his left hand, a hut such as he had previously seen from the sea-shore loomed up, like an excrescence from the white plain.He pulled up, dismounted, and led his horse towards the building.It was partially ruined.The doorway was too low to admit the animal, but going round to the back he found a large gap in the rough mud wall just wide enough to allow the horse to pass.Here at least there was temporary shelter for both man and beast.True, there was some risk of the Cossacks appearing even yet; but the horse could go no farther; while it was resting the snow-storm might cease, and with a lifting sky he might be able to take his bearings and strike out a definite course.Leading the animal into the hovel, he scraped the snow from its body, rubbed it as dry as possible with the cloths he unrolled from the saddle, and sat down on a billet of wood, cold, hungry, and depressed.

Thinking, dreaming, he at length fell into a doze.When he awoke, he noticed that the snow had ceased, and the sky was clearing.It was four o'clock.Rising stiff with cold, he went outside the hut and observed a streak of dull red on the horizon.

"That must be the setting sun," he said to himself."I wonder if, guiding myself by that, I could by and by reach a village and get food.Poor old horse!I hope you are not feeling as hungry and miserable as I am."

He led the beast out and mounted.It was now freezing hard; the snow gave a metallic crunch under the hoofs as he rode away.Westward, towards the setting sun, must lie the sea; in that direction there was nothing to hope for.Northward were the Russians, southward the Japanese, but how far away?His course must be eastward, for sooner or later he must strike the high-road, and when once on the high-road he must in time reach a village.There would always be the risk of meeting Russians, but he could only chance that.Eastward, therefore, he set his horse.His advent in a Korean village would not be without danger; but one peril balanced another, and his plight could scarcely be more desperate.

He had ridden, as he guessed, some three miles farther across the valley, when suddenly, in the dusk before him, he descried a cluster of huts."At last!"he said to himself with a sigh of relief.Here at any rate were people; where people were, there must be food—and food, both for himself and his horse, must be obtained, whatever the risk.The hamlet might harbour a Cossack patrol; but at this stage Bob felt that it was no worse to fall into Russian hands than to die of famine on the snow-clad hills.On the other hand, if there were no Cossacks in the hamlet, his own appearance in Russian guise would be sufficient to procure him supplies.The Korean as a fighting man was not, Yamaguchi had told him, very formidable, so that even if the villagers proved hostile he felt that he could manage to hold his own.

Taking the Cossack's pistol from the holster, Bob rode on boldly into the hamlet.To assure himself that it sheltered no Russians, he cantered right through the narrow street, then turned his horse and made his way to what appeared to be the principal house.Like all Korean villages of the poorer sort, this one was dirty and cramped, consisting of a few one-story houses of mud with thatched roofs.The street was now deserted; the few people who had been in it when he cantered through had scattered into their houses when they saw him turn, regarding him no doubt as the pioneer of a body of Cossacks.He dismounted at the closed door of the hut, and knocked.There was no reply; save for the bark of a dog the whole village was shrouded in silence.He knocked again, and a third time, still without effect; the fourth time he battered insistently on the door with his pistol.Then he heard a sound within; the door opened, and by the dim light of a foul-smelling oil-lamp he saw a very fat elderly Korean spreading himself across the entrance.

Bob knew no Korean, no Russian, no Chinese, and only a few words of Japanese.These he had perforce to rely on.

"Komban wa!"he said politely, giving the evening greeting.

The man snapped out something in gruff tones.

"Tabe-mono!"added Bob, taking a few Japanese coins out of his pocket."Uma!Pan taberu daro!"

The Korean shook his head and began to jabber words incomprehensible to Bob.His meaning, however, was obvious; he was not inclined to supply the food for horse and man for which his visitor had asked.Bob was in no mood to brook reluctance or even dilatoriness.Raising his pistol and pointing it full at the man's head, he poured out a torrent of the first abuse that came to him, which happened to be phrases he had heard addressed to the referee at football matches in the Celtic Park.No Korean, as he had expected, could stand up against this.In a short time a feed of corn was brought for his horse; he tied the beast up at the door, and returning to the room sat down on the stone floor, awaiting food for himself, and wishing that the furnace in the cellar beneath were not quite so hot.The air inside the hovel was foul and suffocating, but a man can put up with a good deal of discomfort when he is starving, and Bob did not turn up his nose at the evil-smelling mixture by and by set before him.It was a dish of which the poorer Koreans are fond—a compound of raw fish, pepper, vinegar, and slabs of fat pork, and the odour was like mingled collodion and decaying sea-weed.He tasted it, tried to swallow a mouthful, found it impossible, and then, in a burst of scarcely feigned rage, demanded meshi or boiled rice, which he had reason to suppose would be at once more palatable and more trustworthy.This was in due course forthcoming, and with the aid of a spoon, the only one the house contained, he succeeded in disposing of a quantity of food which would have astonished anyone but a Korean.His host had now become cringingly polite.Bob questioned him, partly by signs, partly by means of his few words of Japanese, regarding the direction of Seng-cheng and the Pekin road.The former, he learnt, was 70 li (about 21 miles) over the hills, the latter 10 li due east.Thinking over the situation, he resolved to make boldly for the road, which he knew led direct to Ping-yang, and on reaching it to travel by night and rest in hiding during the day.Having made a hearty meal, with a moderate potation of a thin rice beer which he found very refreshing, he rose to leave, and offered the Korean a yen, which, as prices go in the country, was probably four times the value of what he and his horse had consumed.The man, with many bows and protestations, refused to accept payment.Bob insisted, the Korean resisted, and, pointing to a wooden pillow-block on the floor and a quilt hanging on a peg, tried to persuade his visitor to stay the night.This invitation was politely declined, whereupon the Korean in his turn became insistent, so that Bob grew suspicious.The man's refusal to accept money was no doubt an attempt to ingratiate himself with the Cossack patrol to which he supposed Bob belonged; his pressing invitation was capable of a less amicable explanation.Bob in his guise as a Cossack would never think of spending the night alone in a Korean village; if he fell asleep he might never awaken.Shaking his head resolutely, he made signs that he wished the remains of his meal to be put up for him in one of the lacquer boxes he saw in the room.This having been done with manifest reluctance by his host, he moved forward his horse, the Korean following him still with pressing entreaty.All the time that Bob was bundling up a supply of fodder for his horse the man stood jabbering at his side, but he withstood these persevering efforts to detain him, and was just about to mount his horse, when he saw dimly in the dusk, at the end of the street by which he had entered the village, a body of men whom even in the distance he recognized by their quaint caps and baggy clothes as Korean infantry.

Instantly he vaulted into the saddle.At the same moment he heard the bang-bang of rifles and a volley of shouts.His fat host flung himself flat on his face, and Bob galloped up the street, smiling at the ineffectiveness of the Koreans' aim, and wondering how long it would take them to reload.At a turn of the street, even more to their surprise than to his own, he came plump upon another body of Koreans marching in no great order in the opposite direction.Evidently a clumsy attempt had been made to surround him.There was no alternative.He dashed straight at this new body; they scurried like rabbits to the sides of the road, yelling with fright, and by the time they had recovered sufficiently to remember that they were soldiers of the emperor, Bob was out of sight.

Only a few minutes after Bob had thus routed a Korean detachment, two Chinamen rode in at the other end of the village.They were shorter than the average Chinaman; yet, mounted as they were on the high saddles usual in Korea, their feet nearly touched the ground at the sides of their diminutive and sorry-looking ponies.They dismounted at the door of the house that Bob had lately left, and then it could be seen that the younger of the two was dressed like a respectable Chinese merchant, the other being evidently his servant.

The merchant enquired of the Korean at the door what was the meaning of the sounds of firing he had heard.

"The soldiers were honourably shooting at a Russian," replied the man.

"Did he have his lance?"asked the Chinaman instantly.

"No; but a pistol."

"You are sure he was not a Japanese dressed in Russian clothes?"

"Yes; he was tall, his cheeks were red, his eyes were blue, his hair the colour of ripe corn; there is no doubt at all that he was a red-haired barbarian."

The merchant spoke a few words to his servant; then both remounted, and set off as fast as their Lilliputian steeds could carry them after the departed Cossack.

Bob meanwhile had been hastening on.During the day his horse had had nearly five hours' rest, and after its good meal was again comparatively fresh.Scrambling over the hills, in no little danger of coming to grief in the darkness, he at length struck the beaten track over the snow that alone marked the course of the high-road.It rang hard under the horse's hoofs; much heavy sled traffic must have passed over it—no doubt supplies for the Russian cavalry, scattered over the whole of Northern Korea.All the way as he rode, Bob was alert to catch any sound of approaching troops, but the highway was deserted; he met neither man nor beast.After covering about ten miles he thought it best to leave the road and strike off into the hills on his left, with the object of skirting round Seng-cheng, which he felt sure was occupied by a Russian force, large or small.Choosing a spot where the highway edged a clump of wood, he rode some yards among the trunks, dismounted, and then carefully smoothed over his horse's tracks on the snow, leaving no track himself by retreating in the hoof-marks.Then he plunged deeper into the wood, in a direction at right angles to the road, leading his horse in order to avoid collision with the trees, and hoping by and by to reach some woodman's hut where he might safely pass the rest of the night.A faint moonlight began to shine through the leafless skeletons, assisting his progress.After half an hour he came suddenly upon a somewhat extensive clearing, in the midst of which he saw a small cluster of huts similar to those he had left behind.He was about to turn sharply off to avoid them, when something in their appearance struck him as unusual.Leaving his horse, he advanced cautiously, and found that the huts were deserted and in ruins; the blackened thatch and mud told a tale of burning, and Bob surmised that here was evidence of a Cossack raid.After a little search he found a hovel that had suffered less than the rest.He easily broke a way through its wall for the horse, returned and led the animal in, barricaded the opening with debris from the other huts, and made himself as comfortable as he could by means of the cloak and horsecloths rolled up before and behind the saddle.Then, being by this time dead beat, he soon fell asleep.

Just as dawn was breaking, he was startled from his heaviness by the loud snorting of his horse.Springing up on his elbow, he saw in the wan light the animal, its ears thrown back, its eyes protruding, tugging at the reins by which Bob had secured it to one of the beams supporting the roof.It was panting, trembling, frantic with fear.Wide awake in an instant, Bob reached for the case containing his rifle, which he had worn slung over his shoulder and removed on lying down.Even as he did so the faint light filtering through the loosely-barricaded doorway was obscured.There was a thump and the crash of falling woodwork, and a heavy body, in the suddenness of its onset looking even larger than it was, sprang between him and the horse.A shrill scream of fright, followed instantly by a dull thud, then a deep growl, and Bob, though he had never heard it before, was in no doubt what the sound implied: it was the warning growl of a tiger after a kill.Stretched upon the inanimate horse, he saw in the uncertain light a huge tawny form.Its back was towards him; its tail was lashing the ground within a few feet of where he had lain; in a moment it must scent him.To gain the door, even had there been any prospect of safety in flight, he would have to pass immediately behind the brute, which at the sound would turn in far less time than he would take to rush past.The beast was still growling and lashing the floor.Bob remained still as death, in the reclining posture in which the tiger's entrance had surprised him.In a flash he saw that his only chance lay in one shot so well aimed as to kill or maim the brute; if he missed, nothing could save him; yet the slightest click or rustle would not escape its sensitive ears.Even as he raised the rifle to his shoulder with all his care, the tiger heard the movement and half-turned its head.But its head was still too much covered by the length of its body for Bob to risk a shot at its brain, and he knew that in the sudden volte-face that was now bound to come the movement would be so rapid that he might very easily miss.Instantly leaning forward, he brought the muzzle of the rifle within a foot of the animal's body at the region of the heart, and fired.There was a scream of rage, a convulsive twist of the huge body, a leap, and Bob was on the floor, beneath the tiger, unconscious.

CHAPTER X

The One-Eared Man

Mr. Helping-to-decide on Tour—Watched—The Tragedy of the Topknot—A Vampire—Mr. Helping-to-decide at Home—An Unholy Alliance—Cross-Examined

"How do you do, sir?I trust you enjoy excellent health and spirits."

These were the first words Bob heard when he came to himself.He was surrounded by a group of Korean soldiers, about whom there was nothing martial but the blood-red band in their hats.In the centre, just alighted from a palanquin, was a Korean in long white cloak and a hat like an inverted flower-pot; he was bowing and smiling with a mingled expression of amiability and concern.Bob recognized him in a moment; it was Mr. Helping-to-decide.

"Thank you, I'm rather shaky," said Bob looking round."What has become of that brute?"

"Outside, sir.You stop horses; you stop tigers too.You kill him stone dead, sir."

"Did I really?The last I remember is an uneasy idea that the tiger was going to kill me.D'you mind giving me your hand.I feel rather giddy and battered."

With Mr. Helping-to-decide's eager assistance he rose to his feet and staggered out of the hut.There lay the tiger, a fine animal nearly twelve feet long.Beside it was the horse, whose skull had been broken by a single blow from the tiger's massive paw.

"I wonder I escaped," said Bob.

"A good, a famous shot, sir," said the Korean; "but you have a scratch, an abrasion, on your nob just where your hair begins."

"Have I?I am lucky it is no worse.But how is it I have the pleasure of seeing you here, sir?"

Then Mr. Helping-to-decide explained that he was on the way to his country house some fifteen miles distant.He had been sent by his government to watch the Russians at Seng-cheng, and had gone into the town with the full determination to let nothing escape his attention.But the Russians objected to being watched.They peremptorily ordered him out of their lines, and compelled him to disband his troops, allowing him to retain only the small escort which Bob saw with him.He was following his wife and family, who had preceded him along the road, when the sound of a shot had arrested his progress, and on searching he had found the tiger in the throes of death, and underneath it the inanimate form of the man to whom he owed eternal gratitude.If only he had been a little earlier he might have killed the tiger before it made its spring, and so have saved his honourable benefactor the bruises he was sure he bore on his body and the cut he saw on his head.Still, he hoped that he might some day have an opportunity of doing something in return for the Englishman's condescending kindness.

It was now several years since Mr. Helping-to-decide had eaten his dinners at Lincoln's Inn, but he spoke with extreme volubility, and was seldom at a loss for a word.Law lecturers, London landladies, leader-writers and cabmen had all assisted to form his style.

"Many thanks," said Bob."Really you are too kind.I am very glad to have met you, as, knowing the country, you may be able to assist me to escape."

"Certainly, sir, with the greatest pleasure.If you will come with me, no wild beasts will dare to molest you."

"I wasn't thinking of wild beasts," said Bob with a smile."I was thinking of Russians.The Cossacks are after me."

An instantaneous change took place in the expression of Mr. Helping-to-decide's features.He glanced round with a quick movement like that of a startled hare, and peered among the trees as though expecting to find a Cossack behind every one of them.

"I don't think they are here just now," added Bob, repressing a smile.He proceeded to give an account of the circumstances that had brought him to that spot, the Korean listening with gathering apprehension.

"This is a most astounding fix," he said."The Russians are very hostile, very unkind.They are on all sides" (he made a wide sweep with his arm); "they will find you, and then, hon'ble sir, what in the name of goodness will you do?You are more than a match for a horse, you have considerable facility with tigers, but with a Russian—ah!that is ultra vires.Why, would you believe it?—they treat me, who help to decide in the War Department of his Imperial Majesty—they treat even me as if I were a dog!It is a jolly astounding fix!"

The little man looked so sincerely perturbed that Bob made an effort to keep a grave face.

"It is very kind of you," he said, "to feel so much anxiety on my account.After a short rest I shall be well enough to push on.I shall have to do so on foot, unless one of your men will sell me his horse.I could give him a bill on Yokohama."

"On no account whatever, hon'ble sir.I am still head over ears in your debt.Do I not owe to you preservation of my better half?Yes, by gum!Now, sir, if you will do me the honour to ride in my insignificant conveyance, I will have you transported to my humble roof, where the weary are at rest, and we can there enjoy sweet converse about via media in these awkward circs."

Bob did not much relish the idea of proceeding over the roads cooped up in the narrow space of a palanquin carried by coolies, but the Korean's anxiety that he should keep out of sight was so evident that he decided to accept the offer.He returned to the hut to fetch the Cossack's cap, cloak, and rifle, and his own glass, but when he reappeared with them, Mr. Helping-to-decide again looked startled and begged him to leave them behind.Bob yielded, except as to the glass.A Korean cap was found among the official's belongings, and with this perched on his head Bob crept into the palanquin, prepared to endure an uncomfortable journey.

Just as the party was about to move off, one of the escort approached Mr. Helping-to-decide, and, first humbly kow-towing, said something in a tone of supplication.The functionary explained.The men would like the horse; would he allow them to cut up the animal?Bob declared that he had no objection whatever; whereupon Mr. Helping-to-decide told the men that they might have the horse if they first skinned the tiger.A dozen men at once set to work, and in half an hour the double operation was performed; the dismembered horse was distributed among the escort, the tiger's skin was entrusted to the head coolie, and after this long delay the party resumed their northward journey.

As they left the group of huts, no one noticed two Chinamen crouching in a ruined cabin, within a few feet of Bob and Mr. Helping-to-decide.They had seen and heard all that passed since the arrival of the Koreans.When the party had finally departed, the Chinamen left their place of concealment, struck through the trees in a north-westerly direction, and presently reappearing on their little ponies, made off towards the Ping-yang road.

Mr. Helping-to-decide rode by the side of the palanquin, the top of which was lifted up, and showed himself anxious to keep up his guest's spirits by a never-ceasing flow of conversation, to which Bob listened with a fearful joy.He explained that the Koreans were deeply interested in the result of the war, for it appeared inevitable that the country must come under the dominating influence either of Russia or of Japan.They would rather have neither, but if it must be one or the other, they preferred Japan to Russia.But there was one particular grudge they had against Japan.It was due to Japanese influence that the Emperor of Korea, some years before, had decreed the abolition of the topknot and plunged the whole nation into despair.

"Dear me!"said Bob."I should have thought it the other way about.The cultivation of the topknot must give you a good deal of trouble."

"Ah!You are a barbarian—excuse me, a foreigner; you do not understand.How should you?In your country what do they do to a man when he is grown up and becomes married?"

"I don't know that they do anything—except send in tax-papers, and that sort of thing."

"Well, in my country we wear cranial ornament—topknot to wit.In Korea the topknot is a sine qua non; without it a Korean has no locus standi: he is a vulgar fraction—of no importance.Let me inform you, hon'ble sir, a gray-beard, though of respectable antiquity, if minus a topknot, is to all intents and purposes a baby-in-arms. That is our Korean custom.Now, hon'ble sir, can you imagine our unutterable consternation, perturbation of spirit, nervous prostration, when an Imperial decree issues—every conjugal Korean's topknot shall be abbreviated, cut off instanter!There is dire tribulation, sore perplexity.All Korea plumps into the depths of despair.Besides, it is the height of absurdity.How, hon'ble sir, shall distinction henceforth be drawn between celibate irresponsible and self-respecting citizen with hostages to fortune?That is what we ask ourselves, and echo answers, how?I pause for a reply."

Bob, chuckling inwardly at Mr. Helping-to-decide's wonderful command of the English tongue, looked sympathetic, and said:

"It was very awkward certainly.But what happened?"

"At promulgation of decree I was residing at my eligible country house.By gum, I think, such humiliating necessity cannot embrace the Cham-Wi—hon'ble helping-to-discuss in his Majesty's War Office.Perish the thought!But, hon'ble sir, stern duty calls me to metropolitan city.I arrive at the outer gate.Lo!I am arrested, I the Cham-Wi, by guardian of the peace—copper, who stands outside with huge shears ferociously brandished.I make myself scarce—bunk.Alas!vain hope: a brawny arm seizes me from behind; one, two, the deed is done; my topknot—where is it?It is beyond recall.I am dishonoured.Behold me on my beam ends!"

The recollection moved Mr. Helping-to-decide almost to tears.Having recovered, he went on to explain that a domestic revolution soon afterwards removed the emperor from the influence of his evil advisers.The decree was abrogated; and since then the Koreans had cultivated topknots anew, and had again become honourable men.

In spite of this bad business of the topknot, Mr. Helping-to-decide was quite emphatic in his preference of the Japanese to the Russians, and he was glad to know of the successes of the former at Port Arthur.He was able to give Bob some information about the progress they were making in Korea.Their armies now stretched in a long front of some fifty miles, and were only waiting for the break-up of the ice to press forward to the Yalu.Between their present position and Wiju there were five rivers in all, which would require to be bridged, but this would give little trouble to the Japanese engineers, who were exceedingly quick and capable.They had also exact information of the Russian dispositions.Many Japanese, disguised as Chinese or Koreans, were constantly moving in and out among the Russians, carrying their lives in their hands.Several had been caught and shot, but more had escaped detection and brought valuable information to their generals.The Russians were doubly incensed at this because they were unable to play the same game.While the Japanese were perfectly at home in the country, and were moreover very skilful in disguising themselves, no Russian could easily pass for a Chinaman or a Korean, for even if his physique were not against him, his ignorance of the languages would prove a serious drawback.

"That makes me wonder what I am to do," said Bob."I want to reach the Japanese lines, and the disadvantages of the Russian are disadvantages in my case also."

"You must come to my house; we will disguise you,—make you look quite the lady.Then you can ride in a palanquin to the south, and I will send trusty men to guide you and bring you o.k.to the Japanese."

Bob was not enamoured of the suggestion, and hoped that some other means would offer.Meanwhile, having no alternative to suggest, he said nothing.

Twelve miles of the journey had been accomplished, at a terribly slow pace, and three more remained to be covered, when an old and weather-beaten Korean riding a pony appeared rounding the shoulder of a hill not far ahead.He quickened his pace when he saw the cavalcade, and on meeting Mr. Helping-to-decide entered into grave conversation with him.Bob, watching the functionary's face, saw its expression become more and more agitated and alarmed.He came at length to the palanquin, and explained that the rider was the sergeant in charge of the village they were approaching, and had come to report that during the past few days a notorious Manchu brigand, in Russian pay, had been raiding within ten miles of the village under pretence of reconnoitring.He was a man whom the people had long had reason to dread.During the war in 1894 he had committed terrible atrocities in Northern Korea, and had since infested the upper reaches of the Yalu with a band of desperadoes, terrorizing a district several hundred square miles in extent.His head-quarters were supposed to be in a mountain fastness some distance beyond the Yalu.Before the outbreak of the present war the Russians had more than once attempted to extirpate his gang, but he had always proved too clever for them.They had now come to terms with him, and were utilizing his great knowledge of the country and his undoubted genius for leadership.He was a most accomplished linguist, speaking every dialect of the Korean-Manchurian borderland, besides having a good knowledge of Japanese, a smattering of Russian, and a certain command of pidgin English.In his early youth he had been a trader on the Chinese coast, but it having been discovered that he was in league with pirates, he had suddenly disappeared, being next heard of as ringleader of his desperate band of brigands.He was utterly unscrupulous, and the fact that he was now acting with the Russians only increased the gravity of the news that he was in the neighbourhood of Mr. Helping-to-decide's home.

The Korean was much depressed during the remainder of the journey, and spoke but little.He cheered up, however, when the village at length came in sight.It was evening; only women were to be seen in the street, for it is the Korean custom for the men to remain indoors after nightfall, and leave the streets free for their women folk.Mr. Helping-to-decide rode through the village till he came to the only house of stones and tiles which it contained, where, dismounting, he politely invited the honourable sir to deign to enter his contemptible abode.Bob was very glad to stretch his limbs after many hours in the palanquin, and, slipping off his boots at the door, found himself for the first time an inmate of a Korean house of the better sort.

He could not help comparing it unfavourably with the Japanese interior he had found so pleasant at Nikko.There was a striking lack of the simple grace of Kobo's house.The room to which his host led him was small and bare.The tiled roof was supported on a thick beam running the whole length of the house.In place of the spotless mats of Kobo's rooms there was a dirty leopard-skin and an expanse of yellowish oil-paper covering the whole floor.The walls were of mud and plaster, with sliding lattices covered with tissue-paper that also appeared to have been well oiled.One or two jars and a lacquer box completed the furniture.

He saw nothing of Mrs. Helping-to-decide.The evening meal was shared by himself and his host alone.The food brought in by the female servants was sufficient for a much larger company.It consisted first of all of some questionable sweetmeats; these were followed by raw fish, underdone pork chops, rice in various forms, radishes of gigantic size, and fruit, including dried apples and very tough and indigestible persimmons.Bob knew that he would be regarded as impolite if he refused to partake of all these dishes.He did his best, but found it difficult to swallow anything but the rice, in the cooking of which the Korean excels.His poor trencher-work was, however, put to shame by Mr. Helping-to-decide himself, who disposed of course after course with a gusto which would have amazed his visitor had he not heard extraordinary stories of the capacity of the Koreans in this respect.When the meal was over, Bob was not surprised to see his host fall asleep, and being thus left to his own resources, he rolled himself up in his cloak and a silk coverlet provided by one of the maids, and made himself as comfortable as possible on the floor.

He passed a most uneasy night.He had not been long asleep when he half woke with the feeling that his right side was scorching.He turned over sleepily, only to find by and by that the left side was even hotter than the right had been.Whatever position he chose, he could not escape this totally unnecessary heat, which, combined with the unpleasant odour from the oiled-paper carpet, made him wish he could go back to the cold ruined hut in which he had spent the previous night.The explanation was, that beneath the floor was a cellar in which a fire had been lit, and the coolie had piled on enough fuel to last through the night.This was a simple means of heating the house, but Bob could not help wondering whether a refrigerator would not perhaps form a more satisfactory bed-chamber than an oven.

He was glad when morning came, and Mr. Helping-to-decide, awaking from his heavy sleep, had sufficiently regained his senses to discuss ways and means.It soon appeared that the trusty Korean servant who was to have assisted Bob towards the Japanese lines was absent, having gone to keep a watch on the Manchu brigands.Mr. Helping-to-decide accordingly proposed that Bob should remain with him until the man returned, and impressed upon him the advisability of keeping within doors in order not to attract attention.Bob was by no means pleased at the prospect of spending even one day within these close walls, but seeing no help for it he submitted with a good grace.

It was a dreary time.During the morning he was left to himself, and to while away the hours he found nothing better to do than to look out, through a slit in one of the tissued lattices, at what went on in the street.But after the mid-day meal, Mr. Helping-to-decide proposed a game of "go", which Bob knew from previous experience might be spun out to any length.They were in the midst of the game, when there was a great shouting and hurry-scurry in the street; then the clatter of galloping horses.Mr. Helping-to-decide sprang up in agitation, and Bob, going to his slit, saw a troop of Cossacks headed by a tall Manchu galloping up the street, followed by a band of riders, whom from their features and habiliments he concluded to be Manchu bandits.Mr. Helping-to-decide stood in quivering helplessness.The horsemen reined up before his house; some of them went round it in both directions, and the terrified owner turned his white face to Bob and groaned.

When the house was surrounded, the commander of the Cossacks shouted something which neither Bob nor the Korean understood.But the cry was immediately repeated in the vernacular by the tall Manchu; he had dismounted and was approaching the house with the apparent intention of forcing an entrance through the sliding lattice.

"What does he say?"asked Bob.

"He says, hon'ble sir, 'Bring out the spy'," faltered Mr. Helping-to-decide."This is indeed a critical moment.I am at a loss—flabbergasted.I am driven to conclusion it is all u.p."

The Manchu had now come to the wall of the house, and bellowed what was evidently a threatening message.

"'If the spy is not brought out instanter,'" translated Mr. Helping-to-decide, "'he will conflagrate this residence and adjacent village, with incidental murder of inhabitants.'"

Mr. Helping-to-decide wrung his hands in impotent despair.

"I shall give myself up," said Bob.

His host's agitation at once gave place to polite admiration and a show of confidence at which Bob almost laughed.He recognized that it was no laughing matter.The ruined state of the hamlet in which he had met the tiger was clear evidence that the invader's threat was no empty one, and the tales he had heard of the Cossacks' brutality did not promise a pleasant experience to any prisoner who fell into their power.But Bob felt that he had no alternative.There was just a hope that as a British subject he would come off with a whole skin, but in any case it was impossible to let the whole village suffer through any weakness of his.He therefore pulled aside the lattice, stepped out, and with a bold bearing that ill-matched his inward quaking, delivered himself up to the enemy.