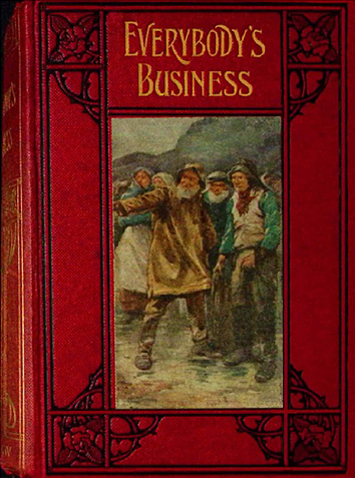

Everybody's business

Play Sample

CHAPTER XVII

MAKING A COLLECTION

THE Vicar was not one who would allow grass to grow under his feet, as the saying is, or who would allow the heated iron to become cold before he struck it.No later than Monday afternoon he set forth upon a round through his parish, subscription list in hand, bent upon getting as many gifts as possible towards the needed lifeboat.He was very much in earnest, very eager in his quest; and, like all subscription collectors, he met with varying success, sometimes receiving more from a quarter where he had expected less, and sometimes receiving less where he had expected more.

The list was headed by ten pounds from himself.This, out of the Vicar's small stipend, after the expenses of his long illness, and considering that he had no private property of his own, meant a great deal more of self-denial than anybody in the Parish was likely to guess,—except indeed his old housekeeper, who "did" for him, with the help of one young girl.But the old housekeeper was no gossip, and Old Maxham was not likely to be the wiser for what she knew.

Mr. Bateson, the doctor, despite his large family, his limited number of paying patients, and his unlimited number of non-paying patients, followed up this donation with another of five pounds; and, to everybody's surprise, Mildred Pattison came forward with a second five-pound note.

Her wish would have been to give it silently, with no name, as a secret token of thankfulness for her own preservation.She could be thankful now, feeling that she had been kept to do some work in life which needed to be done.Sometimes, however, it may be a duty to make one's expression of thankfulness a public matter; and in this case the Vicar was anxious to have the influence of her example for others.Mildred yielded to his wish, simply saying, "I will do as you like."

Mrs. Groates, notwithstanding the pull of her boy's accident, persuaded Groates to offer a pound to the fund; and though he made a long face over it, he gave way.Miss Perkins offered another pound, and this again was a matter for general surprise, since she had never been regarded as of a liberal nature, but rather was reckoned to be parsimonious.Jessie, out of her small purse, bestowed half-a-crown; not without a sigh for the pink ribbon which she had intended to buy.And since the giving of the half-crown meant doing without the ribbon, and since she cared a great deal about having the ribbon, her contribution had the added worth which is involved in self-denial.

Old Adams and the fisherman, Robins, would not withhold their little gifts also, though they had already made the much greater offer of themselves for the work of rescue.Nor were Mrs. Stokes and her husband behindhand; and even wee Posie No.2, with pink cheeks and much excitement, pushed a whole penny into the Vicar's hand.The young Vicar, who dearly loved children, took her into his arms, and kissed the soft little face.

"That penny will surely bring a blessing," he said.

"She's talked of nothing but the boat and the poor sailors, sir, since last Sunday," Mrs. Stokes remarked."You wouldn't think it, to see her, how Posie listens to the sermons, nor how much she understands and remembers.She's such a little thing, but she's wonderful quick to take in things."

"She isn't too much of a babe to listen to the 'old, old story,' Mrs. Stokes," the Vicar said.

In certain quarters matters went less swimmingly.Mr. Mokes, who was credited with large savings, talked of "hard times," and averred the impossibility of going beyond five shillings; a sum which in his case could by no means be reckoned as anything approaching "widows' mites."The Misses Coxen declared themselves to be unable to give anything at all.Work had been slack lately, they said, and money was short, and it wasn't they who were to blame, but other people who ought to have known better; and if those other people liked to give, the Misses Coxen had nothing to say to it, but as for themselves they just couldn't, and that was all about the matter.Other individuals offered more or less, according to their means, according to the claims upon their purses, and according to the spirit of generosity or the reverse which happened to be theirs.

Mokes' very small gift was a disappointment to the Vicar.It might be that Mokes had not so much laid by as was supposed; but as the longest-established and most successful tradesman in the place, he might have given a good deal more than two half-crowns without being a sufferer from his own liberality.The Vicar had looked for at least five pounds from that quarter; perhaps even ten.He spoke rather plainly to Mokes.

And Mokes rubbed his hands deprecatingly and talked anew of "bad times.""He couldn't afford more," he said, "not just then.Perhaps by-and-by—"

The Vicar knew what that was worth.

So the list grew irregularly, as such lists do grow, and the Vicar met with a good deal to encourage him, as well as with a certain amount that was saddening.

He did not, however, depend upon the neighbourhood alone, but wrote to friends and acquaintances and strangers too, in all parts of England, asking them to contribute towards the same object.So vigorously did he exert himself, that in a few weeks he was able to announce good success from the pulpit.He was indeed far from having gained the whole sum, but he had received actually as much as three hundred and fifty pounds; and if he could collect one hundred pounds more, that would suffice.He had been in correspondence with the National Lifeboat Institution; and that Society having just received an unexpected legacy of six hundred pounds towards the purchase of a lifeboat in some locality, where it might be needed, was willing to use this legacy for the needs of Old Maxham.

"The cost of a lifeboat, fully equipped, with carriage and boat-house, amounts to about one thousand and fifty pounds," the Vicar said."That six hundred, with the three hundred and fifty which we have collected, gives us nine hundred and fifty pounds; and I have undertaken, if possible, to get the remaining hundred pounds.When the boat is actually started, there will of course be a certain amount of annual outlay, to keep it in an efficient state,—repairs, salaries to the men, and so on,—amounting to about one hundred pounds a year.For this we shall have a committee and collect what we can, and the rest will be undertaken by the Society.

"And now, my friends, I want you all to help me.Some of you have done much already, I know; and most of you have done something.Still, perhaps you may be able to do just a little more.Think how much the boat is wanted.Think,—if a storm should come,—what a difference the presence or absence of that boat would make!"

And the very next day a storm did come.The winds raged, and the waves leaped in fury over the outlying range of rocks known to Old Maxham as "the reef."All through the evening hours matters grew worse and worse, till only a strong man could stand upon the shore, facing the blast.And in the darkness, those who were there believed that they heard an awful cry, as of human beings in the last extremity of danger.One wild wail, and a pause; then another wilder wail, and a longer pause; then a third—and no more.Some said it was only the shrieking of the gale, and others hoped it might be fancy.

"Even if a barque was on the reef, we couldn't have heerd them here," it was declared.

But the older sailors shook their heads, and said that the thing was not impossible, for such a sound had been heard before, when a wreck had taken place, the wind blowing direct from the reef.Nothing could be done, however; for no ordinary small boat could keep afloat in such a sea as was running that night.

And when the morning dawned, and the fury of the wind had grown less, and the frantic waves had died into a sullen swell, fragments of a broken barque were borne in by the next rising tide, and with the fragments came two drowned bodies of sailors, stark and stiff.Only those two.The rest were gone, and the barque itself had vanished.

They were taken up and were reverently buried in the churchyard, and the Church's prayers were read over them, a large crowd having assembled around.

The Vicar officiated, and he used the opportunity to say a few more words upon the subject which lay near his heart.Many words were not needed, for those two drowned men had cried with a loud voice to the people of Old Maxham.But the Vicar could not quite pass the matter by.He looked round with sorrowful eyes as he said,—

"My friends, if we had had a lifeboat ready, it might be that we could have welcomed these sailors living, in our midst, instead of only giving them a corner of cold earth for their resting-place.

"Who can say?You all know that cries were heard in the night,—cries for help,—and no help could be given.No boat except a lifeboat could have floated yesterday night.

"And whose fault is it that we had not a lifeboat?It is certain that one ought to have been procured, long long ago.I am not going to reproach you now for the past.That which is done cannot be undone; and that which has been undone in the past must remain undone in that past.In the present and for the future it can be done, and it ought to be done, and till it is done we are one and all blameworthy.How many more poor fellows are to die thus, for want of our brotherly care?"

Then a flush came to the Vicar's face."It is nobody's business, perhaps," he said."Nobody's business, in particular; therefore, everybody's business in general.What!—Nobody's business, when we are here, when you and I are here, when God expects us to do what we are able to do!

"Nobody's business!Will that excuse serve, do you think, when we stand face to Face with our Lord, and He searches into our actions and motives and the use that we have made of our time and money and talents?

"Will it do then for us to say, 'It was nobody's business, and so it was not mine!'I think His answer would be, 'The blood of thy brothers crieth unto Me from the ocean.'I think He would ask of us, not, 'Have you bought the lifeboat?'but 'Hast thou done what thou couldst?'

"I cannot judge for one or another of you, whether you have or have not 'done what you could.'But He, your Lord, knows.He never makes a mistake.He never misjudges.He searches into all the underlying motives.

"If you have honestly done your utmost, then you may be at rest in spirit.If you have not, then think of those two poor fellows whom we have laid in the earth: think of all the others who have gone down in the night in an unnamed watery grave.Think of the many more who will yet come to our dangerous coast, and see what you can do, even beyond what you have already done, for their safety."

Tears were in the Vicar's eyes when he stopped, and some of the women present were sobbing aloud.And the Vicar went home and added two more pounds of his own to the collection, resolving to spare them somehow, at the cost of some added self-denial, though he was hardly yet in a condition of health for severe treatment of himself as to food or comforts.

CHAPTER XVIII

WHO COULD HAVE SENT IT?

THAT afternoon the front door of the Vicarage had a busy time of it, and the old housekeeper-cook, Mrs. Maggs, had a busier.No sooner did she get into her kitchen than she had to walk out again.

"There wasn't no getting anything done," she declared."One had need to be made of two, ta answer that there bell, and keep everything going besides."

For the girl was after some rough cleaning and therefore was not presentable for the front door.Still, though Mrs. Maggs complained a little, she was as much pleased as anybody could be, that more money should flow in for the lifeboat.Whether she cared very greatly or no for the lifeboat, she did care for anything that made the Vicar happy, and this lifeboat lay very near to his heart.

First came a succession of notes, or little packages, containing coins; small coins, most of them, perhaps, but none the less welcome for that!Half-a-crown, two shillings, three shillings, one shilling, a sixpenny piece—one after another dropped in, done up in paper or in an envelope; each with name or initials attached, and each given in "for the lifeboat collection."Each in succession was carried by Mrs. Maggs to the study, to gladden the Vicar with fresh hope.

He was trying to get an hour's work over his next Sunday morning's sermon; but the effort seemed likely to be a fruitless one.Note after note arrived, and had to be opened; and then people began to arrive.

Miss Perkins was the first.She had brought ten shillings, and she expressed herself glad to give the extra donation, but she didn't want her name down nor anything said.

"It ain't that I'm making believe to be humble," she avowed with delightful frankness; "but I don't want a lot of talk made, nor the neighbours all wondering however in the world I can manage it.And it isn't nobody's business, except my own."

"You are sure you can afford so much, Miss Perkins?"The Vicar put this question involuntarily.He knew that Miss Perkins had a penniless niece dependent on her.

"I'll make shift to afford it somehow," Miss Perkins responded grimly."I ain't going to have none of them drownded men laid to my score!"And there was the sound of a suspicious sniffle.

Miss Perkins had been present at the funeral of the nameless strangers; and when other people had wept, she had remained stolidly composed.Now her eyes were red, and her pocket-handkerchief was rolled in one hand, ready for emergencies.

"You know best, of course, Miss Perkins.I'm most grateful for your kind help,—and every mother in the land, with a sailor-son at sea, would be the same if she were here now.But I don't ask anybody to give more than can rightly be spared.That would be unreasonable."

"Shouldn't think there wasn't overmuch danger of that, sir!"Miss Perkins sniffled afresh.

"If others respond as quickly as you have done, I don't think we shall wait much longer for the lifeboat," hopefully remarked the Vicar.

Hardly had Miss Perkins vanished, before Mildred Pattison appeared on the scene.

"I've brought another pound," she said simply."And I'm afraid that's the most I can manage."

"I think you have done your share already, Miss Pattison—I really do," protested the Vicar."I wasn't thinking of you when I spoke to-day."

"No, sir.But you made me think of myself.If anybody ought to do more, I'm that one.Saved as I was from out of the waves."

Mildred had brought her invariable companion, Hero, who was always admitted into the Vicarage.He had grown to be an immense favourite in the place; and with nobody was he more of a favourite than with the Vicar.Mr. Gilbert's hand rested on the dog's great solid head, as he talked with the dog's mistress.

"But you lost your all on the rocks when you were saved from the wreck.If any one had a reason not to give, some would say that you were that one," the Vicar added impulsively.

In the churchyard he had seen only the other side of the question.Now he was realising how much was meant in the lives of Old Maxham people by the self-denying gifts for which he had pleaded so strongly.

"I don't see it so, sir.And if you don't mind me saying it, I doubt if you do either."

The Vicar smiled."No, you are right," he said."I do not really, perhaps.It was no hardship for your dear ones to be called home as they were.The only hardship was for you—not for them.We may be very sure that they would not wish to come back here, if the choice could be given them.It has been a sore trial for you to lose them, but you may indeed be thankful,—both for them and for yourself."

Mildred's eyes were full.She wiped away the tears, and said simply,—"I do try."

After Mildred's departure, in walked the doctor.

"Now, I say, Gilbert, this sort of thing won't do," Mr. Bateson."You're enough to worm a toad out of a stone.As for giving more, I can't afford it, of course,—but there's no resisting you.Here,—" and he slipped a gold coin into the Vicar's hand."You may have that, and that's all.Can't do more.There's no end of broth and good things wanted just now among my poorer patients.Glad to do all I can, but limits must exist.Well—I hope you'll succeed in the end.Nothing like perseverance.I've tried to stir the sensibilities of a patient of mine, just come down from London; perhaps I ought to call him a 'paying guest,' rather than a patient.One might as well try to rouse a log to generosity.He really isn't badly off, and he might have spared you at least a few shillings.He didn't seem to look upon the matter in that light: and one man can't see with another man's eyes.Good-day, and don't make yourself ill over this business."

Then was ushered in Alice Mokes, the silent and useful daughter whom everybody liked and few knew well.She had no message from her father, but she brought two shillings out of her own little store."I wish it was more," she said sadly."I haven't much."

"That makes the more of the little that you can give, Alice."

"I'd make it more if I could," she said, hardly grasping his meaning."I did think father might—but—"

"No hope in that direction, I suppose?"

She shook her head."If father once makes up his mind, nothing turns him from it," she said."And he has made up his mind."

"Was he at the funeral?"

"No, sir.He said he couldn't spare the time."

Alice had a class in the Sunday school, and she stayed to ask a question on some point that had puzzled her.The Vicar explained her little difficulty with clearness, and she tripped off smiling, only to make way for Mrs. Groates.

"Come in, Mrs. Groates, come in.I'm glad to see you," the Vicar said, with his heartiest welcome."How are you getting on?Jack all right?"

"He is; thank you kindly, sir.And I've brought just half-a-crown for the lifeboat, and I wish it was ten times as much."

"So do I, Mrs. Groates, because that would show your husband's business to be prospering particularly well.However, I hope it does prosper.Of course you are a large party, and you have a good many expenses.Sit down, and tell me all about yourselves.Stop a minute; I'll note this down.'Mrs. Groates, two and sixpence.'That's right.I didn't think your husband looking well the other day?"

"No, sir.Nor happy."Mrs. Groates spoke with emphasis.

"Sorry for that.I hope nothing is wrong—You are such a happy-looking woman yourself—"

"I'm glad to say I've always been blessed with good spirits.But Jim, he's more of an up-and-down sort; and it's been all down lately, not up.He don't and won't tell me why, and I thought I'd just mention it to you, sir, thinking maybe you might some day have a bit of a talk with him.If anything is gone wrong, he'd tell you, perhaps, when he won't tell me."

The Vicar thought this doubtful, but forbore to say so.

"We've had a lot of talk lately about my boy Jack—our boy I mean.Jack's always been a good boy to me, sir; the best boy a mother ever had.I've never had a hard word from Jack, not since he was a baby.But you know he's engaged to be married now."

"I know.To Jessie Perkins.Nice girl too."

"Yes, she's a very nice girl, sir; I wouldn't wish a nicer for my Jack; and nobody could wish a better young man for her than him.Jessie always was nice, but she's ever so much nicer since Miss Pattison went to live in that house.She's done a lot of good to Jessie.But it was about Jack that I wanted to ask you, sir.I do think, and so does Jack, that he'd ought to be in some other place, and doing something better than he's doing now.It's all very well his helping in our shop, but that won't lead to nothing better by-and-by; and there ain't no real need for Jack to help.Mimy and me can do all that's wanted.It isn't as if the shop was so very big, nor as if the business was getting to be more and more, for it don't; and I don't mind saying that to you, sir, though I wouldn't like it to be farther."

"No, no, I'm safe.You may trust me.Perhaps that is what troubles your husband."

"Maybe so, sir.I couldn't say.He won't allow that things ain't all just as they should be—and maybe they are better than I think.But I do know Jack had ought to get something better to do.He'd ought to be in some biggish town, where he can learn his business thoroughly, and hope to rise by-and-by.I've always told them so, and Jim wouldn't listen, and Jack didn't mind.Jack's easy-going, you know: and he's a good home-boy too, and didn't want to leave us all.But now he's thinking of getting married, it makes all the difference.He don't like the thoughts of going, but all the same, he knows it's got to be, and wants it as much as anybody."

"Yes, yes, I see.And what does your husband say?"

"He don't seem over well pleased, sir, but he don't say much.He's sort of gloomy-like, and don't talk much about nothing.He says he s'poses Jack 'll have to do as he chooses."

"And you want me to help you.I'll think about the matter.Perhaps I could write on his behalf to one or two large houses of business, where I am well-known.Worth the trial, at all events."

A little more talk on the subject, and Mrs. Groates decamped, to be followed by somebody else.

So the afternoon wore away; and by the time darkness settled down upon the land, the lifeboat collection had made sensible advance.More than seven pounds had been added to it since lunch.

Seven pounds!But one hundred pounds were needed!

"It will come.We shall get it," Mr. Gilbert said aloud, cheerily."I must send out fresh appeals by post.And now, positively, I must get half-an-hour's reading."

It was early in the week, but the Vicar generally liked to fix upon his next Sunday's subjects in early days, so as to allow time for thought.

A modest little ring presently sounded, and he glanced up to murmur,—"Another half-crown, probably.It is nice to see the dear people responding as they do.Up to and even beyond their ability, I do believe—in some cases.Yet, others could give more," and he thought of Mr. Mokes.

Mrs. Maggs brought another envelope; just a common envelope of cheap white paper, addressed to "The Vicar."

"Who left this, Mrs. Maggs?"

"I really couldn't tell you, sir.There wasn't any name said; and I couldn't even see what sort of a person it was.It gets dark so soon at that back door.Yes, he came to the back door, and he had a sort of woollen muffler up to his face, and he didn't scarcely look at me.He just poked that into my hand, with a sort of a queer grunt, and was of in a moment, before you could say so much as 'thank you.'"

"What sort of man?"

"I couldn't tell the very least, sir.I didn't get a proper look at him at all."

"One of my working-men friends, perhaps,—a little shy of being seen to do a generous act.Another half-crown most likely.Or let us hope for five shillings.Perhaps the name will be inside.Wait, and I will tell you.I really do believe you are as much interested in this lifeboat affair as I am myself.Eh, Mrs. Maggs?"

The Vicar beamed up at her with his bright boy-like smile, and Mrs. Maggs said, "Yes, sir," decorously, with an affectionate glow at her heart.There was not the least need to specify how much she cared for its own sake, and how much for his sake.Perhaps she did not know herself.

A folded blank sheet was within, and inside that sheet were three or four thin papers, at sight of which the Vicar stared in amazement.Across one corner of the blank sheet was written, in a very minute neat hand, "For the lifeboat fund."Nothing more; and no name.The Vicar flushed, and his heart beat fast.

"Bank-notes, sir!!!"said Mrs. Maggs.

"Yes, bank-notes, Maggs!For how much do you think?Maggs, how much do you think?"The Vicar was so excited as to go back to his earlier style of designating Mrs. Maggs, forgetting that he had taken of late to always calling her "Mrs. Maggs," by way of inducing proper respect for her in the village."How much do you think?"he repeated.

"I couldn't guess, sir."Mrs. Maggs smoothed down her apron.

"Ninety pounds, Maggs!There are bank-notes here for no less than ninety pounds!"

"Sir!"

"It's true!Ninety pounds!"The Vicar sprang to his feet, and waved the notes over his head, with a hearty "Hurrah!"which rang through the house.Then he stopped, bent his head, and said reverently,—

"Thank God.Now we can do it."

"Ninety pounds!"repeated Mrs. Maggs.

"Ninety pounds, Maggs!Not one penny less."

"But who—?"both voices exclaimed together.

"Who, indeed?"Mr. Gilbert's mind was already running over the list of his friends and acquaintances in Old and New Maxham, rejecting the thought of each in turn.Most of them simply could not have offered such a gift; and the very few who perhaps could, he felt sure would not.Or if they would, he saw no reason in their case for secrecy.

"It is extraordinary.I have not the vaguest idea who the money can be from.Most singular.Somebody in the place; that seems certain.He must have been at the funeral, or else he must have heard about it from others.This plainly comes as a response.On Sunday—only this last Sunday—I gave out that one hundred pounds more would be required; and the giver of this has evidently reckoned that the neighbourhood might make up ten pounds of that amount.He has reckoned rightly too.Seven of the ten we have already; less than three more wanted.A mere nothing!But ninety pounds!And brought to the back door in such a quiet way.No fuss or ostentation.I am utterly at a loss.And we shall have to be at a loss.The good man does not mean it to be known—whoever he is and of course we cannot try to find out.He has a right to his secret if he chooses."

The Vicar was unable to settle down to any more sermon-preparation that afternoon.He put his books and papers away, and went off to tell his people the good news.Many of them would rejoice heartily with him; not least among them the inhabitants of Periwinkle Cottage.

CHAPTER XIX

JESSIE'S WONDERINGS

"I WONDER, I do wonder, who it could have been.Don't you, Millie?Who ever could have given such a lot?Only fancy—ninety pounds!And this isn't like a big town, where a lot of rich people live.Why, there's hardly anybody in Old Maxham with any money at all to spare.Unless it's the Mokeses.Mr. Mokes wouldn't give ninety pounds, nor ninety shillings, for anybody in the world, except himself.You needn't look so grave, because I've known Mr. Mokes pretty nearly all my life, and I know just exactly what he is.It isn't Mr. Mokes that's given the ninety pounds.And who else it can be, I don't know.Even in New Maxham there's nobody really rich.And nobody likely to give such a lot, all at once, without a word.Who do you think it can have been?What do you think?"

"I think—that skirt has to be finished," Mildred said in tranquil tones.

"I'm getting on with it; I am really.But I'm not like you, and I do get a little excited sometimes.And this is exciting, I am sure.Mr. Gilbert was excited.I never saw him with such a colour."

"Yes; he is very glad indeed.I don't think it is for himself, though.He was thinking of all the poor fellows who might be wrecked upon our rocks; and that now they might be saved."

"And you don't think I am thinking of the sailors too?"

Mildred's grave eyes looked across with a meaning expression."No," she said."I don't, Jessie dear."

Jessie was silenced for several minutes, and her sewing-machine went fast.This was the next morning after Mr. Gilbert's call, with news of his unexpectedly large contribution towards the lifeboat fund, and perhaps Jessie's eagerness was not surprising.Mildred's feelings were deeper, and did not easily find vent in words.

"There!"Jessie said at length, bringing the machine to rest."I've got round that whole skirt, and it's done.It hasn't taken me long either.I should like to go out, and see what people are saying."

"Does it matter what they say?"

"Oh, but I like to know.And perhaps some one may be able to guess who can have given the money."

Mildred was silent.

"Millie, why did you say that just now; you didn't suppose I cared about the sailors?I do care."

"I don't think I said anything about your not caring.It was only a question whether you were thinking of them just then.And whether your being so excited was only for their sake."

"Why should you think it wasn't?"

"I'm not setting myself to judge you," Mildred answered, putting another piece of work into Jessie's hands."Just hem these, dear;—no, not with the machine; and it must be your best work.If you can tell me that you care as Mr. Gilbert cares, I'm bound to do my best to believe you.But it didn't look like that."

"I don't suppose I do, exactly."Jessie spoke in subdued tones."I do care about the sailors being saved, really and truly; but just to-day I suppose I want more to know who has given the money."

"And that is what you are not meant to know.Whoever gave the money intends nobody to know his name, and it is no business of ours to try to find out.Didn't you see?Mr. Gilbert will not try.He may wonder, as you and I do, but he will not stir a finger to find out anything about it."

"Only, if one could just guess—"

"You have been guessing for the last hour.That doesn't do much good or much harm.If you tried deliberately to find out, I think you would be wrong."

"Millie!You didn't give the ninety pounds?"

Mildred laughed."No, I did not," she said."I have not the ninety pounds to give.All the same, I think you were wrong to ask me, if you had the least idea of such a thing being possible."

"I know one thing," Jessie exclaimed."I wish I hadn't given my half-crown."

"Why?"

"Why, what's the use?Two and sixpence!And ninety pounds!Think of the difference.The person who gave ninety pounds could easily have given another half-crown.And I dare say his ninety pounds were nothing to him, and my two-and-six pence was a great deal to me."

"I don't see why you should suppose his ninety pounds to be nothing to him.It may be just as much to him as your half-crown was to you.If not—that would only mean that in one sense your gift was the larger of the two."

"Millie!"

"I mean it really.Did you not understand the Vicar when he preached about the widow's mites?Her gift was actually more than what the rich men gave."

"Now, Mildred!More in a sort of way, I suppose, but not really more."

"I mean what I say.The way God looks upon a thing is the real way, and our way of looking is often wrong.Which do you suppose is most, the half of a thing or the whole of a thing?"

"The whole, of course.At least—well, of course half-a-sovereign is more than a whole five-shilling piece."

"Ah, but that is the wrong way of measuring.It isn't the question, how much a sum of money will buy, but, how much it is out of what a man has.The half of what a man has is always less than the whole of what a man has.If one man has a hundred pounds, and gives ten pounds out of it, then he gives one-tenth of what he has, and he keeps nine-tenths.And if another man has one pound and gives one pound, then he gives his all and keeps nothing for himself.Don't you see?The ten pounds is more in man's sight, but the one pound may be more in God's sight.It is a very simple sum, if one takes it in the right way.I'm not talking now about one's reasons for giving.Only God can know what they are, and we have no business to judge one another's motives."

"But one pound isn't more than ten pounds!"

"It might be very much more to the man himself; and if so, it would really be the larger gift.The man who gave away ten pounds and kept ninety, would not miss so much what he gave, as the man who had only one pound, and who gave that pound, and kept nothing at all for himself.Of course if he was sure of food and clothes and comforts, when he gave his pound, one could not say that he had really had nothing more—even though it might have been the last coin in his pocket."

"And it mightn't be right for a man to give away all he had, if he had children depending on him."

"Certainly it might not."

Jessie worked busily for some time, not talking.

"Do you know about Jack?"she asked suddenly.

"What about Jack?"

"He wants to go away to get work somewhere else.He says he can never get on here.And Mrs. Groates spoke to Mr. Gilbert yesterday—I was there in the afternoon when she came in—and Mr. Gilbert is going to try to help Jack to find something."

"I think Jack is right.It has seemed to me for a good while that he ought not to stay here.There is no chance of his getting on."

"That's what they all say.And Jack wants to begin to lay by.He says he ought."

"Of course he ought.No man has any business to think of marrying, until he has a good hope of giving his wife a comfortable home.If Jack and you were to marry, with nothing laid by, and only just making enough to carry you on from week to week, you would have very little comfort.Loss of work or of health would mean misery at once."

"But it will be so horrid to have him go away from Old Maxham—so dull."

"Not horrid at all, if it is the right thing for him to do.You are both young enough not to mind waiting.Jack will never make his way in Old Maxham."

"He might, if the shop did as well as it ought," meditated Jessie."So Mr. Groates says.He says he has no chance against the Mokeses."

"You see Mr. Groates is comparatively new to the place, and the Mokes family has been here for at least three generations.That makes all the difference."

"I shall be so dreadfully dull," sighed Jessie again.

"O no, you will not.You will be brave and sensible, and make the best of things.You and Jack will meet sometimes, and you can write to one another.And you will both work hard, and not spend all you earn in pretty things to wear."

Jessie blushed a little, and said, "No; but I do like pretty things."

"Most people do.But you are not a child any longer, Jessie.You and Jack are thinking of being married some day; and with that before you, you ought to think of the future.You ought to deny yourself now for the sake of by-and-by.It isn't only yourself that you have to think of—nor even only yourself and Jack."

"Jessie!"called Miss Perkins.

Jessie sprang up and ran out of the room, Mildred following; for something in the tone of that cry was unusual.

"Jessie!"

"I'm coming, aunt.What is the matter?"

The voice was broken and appealing.Miss Perkins stood at the foot of the stairs, holding the baluster with one hand, and holding her side with the other.She breathed hard, as if she had been running up-hill, and her face was yellow-white.The first impression made upon the minds of them both was that Miss Perkins had been taken ill.

"Let me help you into the dining-room," Mildred said kindly."Lean upon me—so—don't be afraid.You will feel better presently."

"Can't I get anything?"asked Jessie.

"It isn't—it isn't—me!I'm all right," gasped Miss Perkins."At least—I'm only—only—it gave me a turn—made me feel like—" and she hid her face in her handkerchief.

"What was it that gave you a turn?"asked Mildred, she and Jessie exchanging glances.

Miss Perkins shuddered.

"Come in here, and sit down.Jessie, get a glass of water, dear.Thank you.Now, Miss Perkins, take a sip or two.Has anything happened?"

Miss Perkins groaned.

"Tell me what it is.Anybody hurt?"

"Killed!"whispered Miss Perkins.

"Who was it?"Both Mildred and Jessie grew paler.

"Killed outright," moaned Miss Perkins."And not a moment's warning!O dear me!"

CHAPTER XX

RUN OVER

"WHO is killed?"asked Mildred.

Miss Perkins shivered, and Jessie stood gazing in a vague dismay.

"Tell us what has happened, and who is killed," repeated Mildred, pressing her hand gently upon Miss Perkins' shoulder."I might be some help perhaps.Where did it happen?Near here?Who is it, Miss Perkins?"

Miss Perkins preserved a resolute silence.

"It would be better to tell us at once," Mildred said gravely, and at the same moment Jessie murmured, "Jack!"

"Poor Jack!"sighed Miss Perkins.

Jessie broke into a frightened sob.

"No, no, not that; she does not mean that," said Mildred."Jack is not killed, Miss Perkins!No, I thought not," as Miss Perkins shook her head."Then who was it?Not the Vicar?"

Another shake, and Mildred drew a breath of relief.

"Just out in the street," Miss Perkins began, suddenly finding her voice."And I'd been talking to him only one minute before.He said it was a fine day, and I said yes, it was.And he said he didn't think it would be so fine to-morrow, the clouds were gathering up so.O dear, never thinking that there wasn't to be no to-morrow for him!And I said what a wonderful thing it was about the money for the boat, and didn't he wonder who it was that had given it?O dear me!"with another gasp."And he said he wouldn't have thought there was a person in the place as had got anything like as much to spare; and he only knew he hadn't.

"'Times is bad,' says he, with a sort of a melancholy smile, 'and it's hard enough to make both ends meet nowadays,' he says.

"And then I said, 'Good-morning.'

"And he says 'Good-morning.'And then he turned back as I was turning away, and he says, 'So Jack's going to leave us.'

"And I says, 'A very sensible plan too.'

"And he says, 'I'm not so sure about that either.'"

A faint "Oh!"had escaped Jessie's lips, and she looked imploringly at Mildred.

"And then—?"said Mildred.

"And then Mr. Gilbert came up, and he stopped to speak to me; and Mr. Groates was standing in the road, close to the corner, and he stopped to look our way, and nodded to Mr. Gilbert, and I saw Mr. Bateson coming along the road quick.And that very moment Stobbs' cart dashed right round the corner.Nobody could have seen it coming, nor warned Mr. Groates.He was just knocked down flat, and it went over him, and his head struck on the curb-stone.And I was looking, and I saw it all," added Miss Perkins, with unnecessary pity for herself.

"I'm sure it gave me such a turn . . .I don't know whenever I'll get over it.It's made me feel all a sort of upside down.And I couldn't move, no more than if I'd been turned into a stone; but I had to hold on to the lamp-post.And they all came running, and the boy jumped down, and he did look frightened, and no wonder, to see Mr. Groates lying there on the ground.But nobody hadn't time to see to him, though I'm sure he deserved a scolding, tearing round corners at that rate.It's a shame the way those butcher boys do go about.I wonder people aren't killed every day.The boy said the horse was running away, and he couldn't hold it in; but there's no knowing whether he spoke the truth.

"And Mr. Bateson stooped over Mr. Groates, and looked into his face and felt his pulse, and we all waiting round, not knowing whatever was going to happen.And Mr. Gilbert said something quite low, so as I couldn't catch it, and Mr. Bateson shook his head, and said, says he, 'Quite dead!'That's what he said, as plain as I'm speaking now.'Dead!'says he, and he seemed mighty sorry too."

"Jack's father dead!"Jessie broke out in bewilderment.

"That's what the doctor said; and Mr. Gilbert asked if he was sure, and if there wasn't just a chance, for I heard him.And Mr. Bateson said, no, nothing could be done, and Mr. Groates was killed.It was the blow on the head had killed him, he said.And then Miss Sophy Coxen came and asked if I wouldn't have her arm home, and I'm sure I don't know how I'd ever have got home without.It does give one a turn to see anybody killed like that.But she wouldn't come in, because she'd got to go and tell her sister, and she said maybe she'd be wanted.And Mr. Gilbert, he ran after me, and he says, 'This is awfully sad,' says he, 'and you can tell Miss Pattison,' says he."

"Yes, I will go to them at once."Mildred said, as if in answer to a call.Then she looked at Jessie."Unless you wish it," she added."Dear Jessie, you have a sort of right,—but I think I could be of more use, just at first.If you will stay and take care of your aunt."

"Oh I couldn't help—with him," Jessie said, with a shudder."I should be afraid."

"Not if there was need!No woman who is worth anything will hold back when there is need.You would not be a coward then.But I have had so much more experience, that it is better for me to go now.It will be a sad household."

Mildred ran upstairs and was down again almost immediately, in bonnet and cloak.She kissed Jessie's pale and dismayed face, told her to give Miss Perkins some hot tea, and advised Miss Perkins to lie down for an hour.Then she hurried away.

There was a general air of oppression in the place.A sudden death in a small village is felt by everybody; and Groates, if in no especial sense a favourite, was generally respected and to some extent liked.At all events, his wife and eldest son were liked, and that in no common degree.And this ending to the life of one of themselves had come about with frightful suddenness, without the smallest warning.One moment well and healthy, talking lightly about the morrow's weather, the next a poor helpless body lying in the road, no longer a living man.

Anything so terrible had not happened for a long while.When the drowned sailors were washed ashore, and were buried in the old Churchyard, people had been forced to feel a little more vividly than usual the very narrow line which divides this existence from the next.Still, those sailors had been strangers, men unknown to any one in Old Maxham.Groates was known personally to them all.It was the grim hand of death descending into their very midst, and taking away one of themselves.

Was he ready for the great change?People asked this question with bated breath.Happily it is a question which we are not called upon to answer, one for another.No time at the last had been allowed him, if he had not used the time at his disposal before.It was "fearfully sudden," one and another said.But if he were ready for the call, the suddenness would be nothing.To those who live in daily communion with God, a sudden call Home means only sudden rejoicing.

Mildred might have spent a long time talking in the street, had she been so minded.Several tried to stop her, to see how much she had heard, to find out whether she could give information: but Mildred would not be delayed.Those who wished for a brief talk had to keep pace with her rapid footsteps.

Outside Groates' Store she was literally seized upon by Miss Sophy Coxen, and to escape instantly was beyond even Mildred's power.

"Do tell me how that poor dear Miss Perkins is," panted Miss Sophy, in vehement excitement."She did look bad, and no mistake.And you're going to ask about them over there?O well, I can tell you all you want to know.I've been to the door, and they wouldn't let me in.They won't let anybody in.So it's no manner of use your going.You'll only just give them the trouble of answering the door again.The shop's shut up, and nothing going on.Mr. Bateson and Mr. Gilbert are both there, and I should have thought they'd have wanted a woman to help, but it's no good saying anything.Those Groateses are such queer people, there's no getting hold of them.Then you mean to go just the same!O well, it isn't my fault if you are turned away from the door.That's all I have to say."

Or rather, perhaps, it was all that she had the opportunity of saying, so far as Mildred was concerned.

Mildred attempted no argument, but quietly withdrew from Miss Sophy, went to the door, rang, and was admitted.

"Now, I wonder what that's for?"demanded Miss Sophy in dudgeon."I should have thought I was as good any day as Miss Pattison, and I've been used to turn my hand to things, and I could have been a help.She won't be no sort of good.Well, I do think it's an ungrateful sort of world.The times I've spoken kindly to the Groateses, and the times we've bought things at their shop, just to give them a bit of encouragement, because they didn't seem to be getting on; and then to be turned off like this, and Miss Pattison let in!Pretty near a stranger to the place as she is, and we who've been here for years and years and years!I do think it's a shame.I shan't go to Groates' shop again in a hurry, I can tell them."

Then she remembered that Groates himself was no longer head of that shop, that Groates had passed away from their midst, and her mutterings died away under a sense of awe.

Meanwhile, Mildred passed into the darkened house, and was met first by the Vicar's kind hand grasping hers.

"This is good of you," he breathed."I felt sure you would come.I've had to refuse Miss Sophy Coxen; the poor things seemed to dread seeing her.But somebody is wanted."

"How is Mrs. Groates?"

"Wonderful!I never saw such courage.Took it all in at the first moment, and had him laid on the bed, and insists on doing all that is needed for him herself.She's there now, and I've been thinking who to get to help her."

"I'll go, sir, at once.I can help."

The Vicar looked questioningly.

"Yes, I have done it before.I know what to do."

"Then come this way, please."

Mr. Bateson met them, coming from the bedroom door, and his face gained a look of relief the moment his eyes fell on Mildred."That's right," he said."I can't get Mrs. Groates away, but she must have somebody with her.You can do it?"questioningly, like the Vicar.

"Yes, sir."

"True woman, ready at a pinch!"murmured the doctor.

"According to that definition, a good many women in the world are not true women," the Vicar remarked, in a tone of consideration.

"Very much the other way.It all depends," the doctor said."If a woman thinks first of herself, she is useless; if she thinks of others, she is able to do anything."

"Sad day for these poor Groateses!"sighed the Vicar."Everybody will feel for them.I don't fancy many knew Groates well, but his wife has won golden opinions, and Jack.By-the-bye, where is Jack?"

"Gone to the farther end of New Maxham.I don't think he is expected back for another hour or two,—unless the news reaches him.Stobbs ought to take warning from this, and not let his lads drive at such a reckless pace.If the poor fellow's head had not struck the curb-stone, he might have got off with broken ribs.I suppose there is no more I can do now.I'll look in by-and-by, just to see how Mrs. Groates is.She may suffer later from her courage now."

Mr. Bateson disappeared, and the Vicar waited for what seemed to him a long time.At length the bedroom door opened, and Mrs. Groates came out with Mildred.

"It's all done, sir, now," Mrs. Groates said, facing the Vicar.She was very pale, and her eyes had a curious fixed look, as if she hardly knew how to open them properly; but her voice and manner were composed."Miss Pattison says she'll stay and have a cup of tea with me."

"Yes, yes, quite right.I knew you would find Miss Pattison a help.And . . .one question, Mrs. Groates,—if you don't mind.Can you tell me where Jack has gone?"

A kind of startled cry escaped her.She seemed suddenly to remember that Jack was still is ignorance of the loss which had befallen them.Her hands were wrung together.

"Don't try to say much.Only a word, to tell where Jack might be found.I should like to go after him at once."

"I'm sure it's very kind," faltered Mrs. Groates."Everybody is so kind.He was going to the old windmill, sir, beyond New Maxham, to see about flour.Yes, walking,—he meant to walk both ways.And he was to come home by the sea-road, because Mimy meant to meet him, if she could get there in time."

"Then I will meet him, instead of Mimy.That is better.I will take care how he is told."

"Thank you, sir, kindly;" and Mrs. Groates looked at him with a glimmer of tears in her eyes.She had not yet wept at all."It will be a comfort when my Jack comes back."

CHAPTER XXI

THE TELLING OF THE NEWS

"LET her to have a good cry, poor thing, if you can.Much better for her," the Vicar said to Mildred in a low tone, as he was going away.

Mildred did not find the advice easy to carry out.Mrs. Groates sat down, indeed, by the fire, when desired to do so, and dropped into a waking dream, with the same fixed look in her eyes, and hands clasped forlornly on one knee; but she showed no signs of breaking down.

It so happened that nobody else was in the house.Jack was away on business: the second boy, Will, had been at sea during many months past; the two next boys were at school; while Mimy had taken the youngest boy and girl for a ramble.So there was nothing to rouse Mrs. Groates; and she remained seated, half-stupefied, gazing into the fire.

"Try to take a little tea," urged Mildred.

Mrs. Groates looked at her with blank eyes.

"Just a few sips!"

"Tea,—O yes; thank you, my dear."

But when the cup was raised to her lips, she turned from it."I don't think I can just now.Seems as if I couldn't swallow.I'd rather wait."

Again she sat, lost in thought.Mildred's hand stole into hers, and was gently pressed.

"You're kind to stay with me.It's very good of you.I do feel strange,—it's come so sudden."

"It is terrible for you, poor thing!"

"It don't seem long since that day—when he asked me to marry him.All those years ago.I used to think he'd outlive me—such a strong man."

"No one can ever tell.The strongest are often taken first."Tears were running down Mildred's cheeks, and Mrs. Groates looked at her in a kind of wonder.

"I can't cry," she said."And you can.I wish I could.It seems to have dried away all tears.Poor Jim!"

"He was a good husband to you."

"Yes,—he's been a good husband.Not as he ever was one to say a great deal.But he's been a good husband, and he always meant more than he'd say."Then a thrill of recollection passed over her, and her face changed.

"Yes,—what is it?"

"Something he said only last Sunday,—and I'd forgotten till this minute.I wonder what made him say it?"

"Tell me what he said."

Mrs. Groates' lips were trembling now, and her fingers plucked nervously at her apron.She shook her head as if words failed.

"Tell me.I want to know.What did he say last Sunday?Don't mind crying, but just tell me," begged Mildred."Last Sunday he said,—"

"He said—he didn't know—how ever in the world he'd have managed—if he'd had a different sort of wife.He said—said—'I'm a crusty sort, Jane,' says he,—'but you've been the best thing in my life.'And he says too, 'A good wife is something to thank God for.'"

Mrs. Groates broke down, and sobbed.

"Cry away, poor dear.That will do you good," Mildred said, putting kind arms round her.

And when Mrs. Groates could again look up, her face, though blistered with tears, had lost its strained and unnatural expression.

"Now I am going to make you lie down for a time on the sofa, and you must not talk," said Mildred."Never mind about the children.I will see to them.And Jack shall come to you,—yes, I promise that he shall.I want you to keep quiet.Try not even to think a great deal.Try to feel that you are in the hands of One Who loves you."

"I'll try.My head don't seem as if it could think," Mrs. Groates murmured.

And Mildred hoped that it might be so for a while.

The Vicar had in some respects a harder task than that of Mildred.He went a good distance along the sea-road before descrying Jack.And then he had plenty of time to note Jack's vigorous walk before the two drew near together.Jack was perhaps absorbed in his own thoughts, for he did not see the Vicar until they were only about twenty yards apart.Jack's honest cheerful face lighted up with a hearty smile, and he quickened his pace, but was surprised to have no smile in reply.

"Had he done anything to vex the Vicar?"This idea came to Jack first."And if so, what could it have been?"

"I have come to meet you, Jack.On purpose to meet you.We will walk back together."Mr. Gilbert hoped that Jack would inquire why he had done so; but Jack made no such inquiry.

"That is kind of you, sir.My mother said she'd been telling you about what I wanted to do.I've been wishing to see you.If there was any chance that you could help me, sir,—"

"Yes, we must think about that—another day.Not to-day.I have, just at this moment, something else to say."

"Nothing I have done wrong, I hope, sir.There's nothing I know of,—there really isn't."

"There is nothing wrong whatever, Jack, of that kind."The Vicar laid a little stress upon the word "that."

He hoped Jack might ask a leading question, by saying, "What kind?"but again Jack failed to carry out his expectations.

"Well, I'm glad to hear you say so, sir, for I did feel afraid, when I saw you so grave.Nor nothing to do with Jessie, I hope?"

"No, not Jessie."

"That's righter still.If one of us was to vex you, I'd sooner it should be me than Jessie.She's a good girl, though, isn't she, sir?And she'll make a good wife.To see her working away now at those dresses,—and doing it all as clever as can be.Why, she's making quite a pretty penny; and that's enough to make me all the more impatient to get away and be doing for myself.You see, father doesn't really need me at home.Mother and Mimy can give him all the help he wants.It isn't as if he was an old man.He's in hale middle age still, and he may live another twenty years, for all we know.I hope he will, too.But it wouldn't do for me to stay on in Old Maxham all that time.I've got to make a home for Jessie and me."

The Vicar almost groaned aloud."Jack, don't go on so."

"Did I say anything wrong, sir?"Jack's tone showed surprise."I thought you'd be one to approve.You have said many a time that you wished men would look forward, and prepare a little, and not marry all in a hurry."

"Jack—I've something to say to you."

"Yes, sir.I'd be glad to have any sort of advice.Mother said she hoped you would advise me."

"It's not advice.It's something else."

"Well, sir,—anything you like to say,—I'm sure I'll listen attentive, and I'll try to do it."Jack seemed proof against alarm.

"It's not what you have to do.It is—that something very sad has happened.And I have to tell it to you."

Jack seemed at last a little concerned."Dear me, I'm sorry for that.Nothing very bad, I hope, sir."

"Yes,—very bad, as we men count things to be bad.Not bad, really, for it is God's will; and what He sends is good—even when we cannot see it to be so.It is a great and unlooked-for sorrow."

"Yes, sir;" and Jack waited expectantly.

"There has been an accident."

"Not my mother?Not Jessie?"

"No, neither.But—your father—"

"Something happened to my father!"Jack drew a quick breath."An accident, you say, sir.He has been hurt then?"

"Yes.Very much."

"Any broken bones, sir?"Jack was trying not to show how much he was moved.

"Worse.He was run down by a butcher's cart, dashing round a corner.Your father had no time to get out of the way.He was thrown down, and the cart passed over him."

"Has the doctor seen him?"

"Mr. Bateson was going by at the moment,—and I was there too.It was a sad sight."

"And he's been taken home, of course.Poor mother!That's soon for another accident."Jack's words bore evident reference to his own broken leg in the previous spring."And what does the doctor say, sir?Does he think father will soon be up and about again?"

"No, Jack!"The words, and still more the manner, startled Jack.

"So bad as that!"

"I have not told you the worst.Not only did the cart go over him, but also—his head struck the curb-stone, as he fell.And—"

A long pause followed, which the Vicar would not break.They walked steadily, side by side; Jack's face turned away.The Vicar wondered how far he yet understood.

"If anything could have been done, it would have been done,—with Mr. Bateson there, on the spot.But,—nothing could."

"Yes, sir; I see!"

Another long pause.

"Your mother is a brave woman.You will have to be her stay and comfort now."

"Yes, sir," Jack replied mechanically.The thought arose unbidden,—How about Jessie?And how about his plans for getting away, and for laying by?This would make a great change in his life.How much of a change he could not yet measure or realize; but he would now be the one to whom his mother would look, upon whom she would lean, who would have to take his father's place.How about Jessie?

"Poor fellow!"the Vicar said voicelessly, more than once, noting the young man's absorbed face.

CHAPTER XXII

DIFFICULTIES

THE death of Groates was, of course, accidental; and no other verdict could well be returned by the coroner's jury; but the butcher boy came in for severe reprimand for his reckless driving, despite his excuse that he could not hold in the horse; and Stobbs himself was blamed also.

Steps were about to be taken to enforce, if possible, the payment of some amount of damages to the widow; but Stobbs was a sensible wan, and in view of perhaps finding himself liable for a good deal more, he voluntarily offered, by way of compensation, a sum which it was thought advisable to accept.Mrs. Groates did not move in this matter; and she seemed to shrink from the notion of "compensation," as if the loss which she had sustained could in any manner be "compensated for" by money.When told, however, that it was right for her children's sake, she submitted.

Everybody agreed that it was a melancholy affair altogether, and much sympathy was expressed, which no doubt was a comfort to Mrs. Groates.She needed comfort, for trouble was pressing hard upon her and Jack.Groates had been a singularly reserved man as to his business matters,—very much "shut up," his friends were wont to say; and no one, not, even his wife, knew the precise condition of those affairs.They only knew that money had seemed to be very short, and that the business had not of late increased; and the true state of things broke upon them gradually.

For years past, it seemed, Groates had been getting into deeper and deeper difficulties, had been running further and further into debt.It came as an absolutely new sensation to Jack, when he found that they had been actually living upon borrowed money; money borrowed, of course, at a heavy loss.

The first thing to be done was, if it might be, to clear off liabilities, to settle unpaid bills, and to meet the heritage of debt and confusion which the unhappy man had left to his family.It was extraordinary how he had managed to hide the state of matters from them so long; but no doubt he had buoyed himself up with hopes of improving business; hopes never realized.Had he lived, things might only have grown worse.

They were bad enough already.It soon became evident that one course alone lay before them.The business would have to be sold, and whatever sum they might obtain by that means would have to go in liquidation of Groates' debts; after which Jack would have to begin life anew with a family dependent on him.Will indeed was at sea, pretty well provided for; and Mimy might go out to work in some direction or other; but of the three next boys and the younger girl, only one boy was nearing an age to leave school and begin to "do something" for his livelihood.

All this had to be faced, and Jack did face it bravely.But one thought rose again and again in the midst of other perplexities,—

What about Jessie?

At first he tried to put the question aside.His father's affairs had to be thoroughly looked into; bills had to be examined; plans had to be formed—and the consideration of Jack's own future had to wait, dependent as it was upon the future of others.

Yet in the midst of all that had to be done, this thought would push itself anew to the front, refusing to be silenced,—

What about Jessie?

True, they had had no idea of marrying yet awhile.Jack and Jessie had both meant to work steadily, and to lay by a nice sum each, before they should become husband and wife.Jack had not been willing to condemn his wife in the future to such a bare and squalid existence as too often results from a hasty marriage, upon barely enough for daily food and lodging.He meant Jessie to know comfort in her home; he meant to provide beforehand for probabilities; he meant to have somewhat to fall back upon when the inevitable "rainy day" should occur.

All this had now become impossible.Jessie might work as she willed for the needs of by-and-by; but he was no longer free to do so.The utmost that he could hope to earn, perhaps for many a year, would do no more than keep his mother and the children afloat.

Could he ask Jessie to wait, in the hope that some day he might be free?That "some day" might lie far ahead.What if it should mean eight years, ten years, twelve years of waiting?Would Jessie be willing?

True, there was another mode of action which some young men in his position might have adopted.He might simply please himself in the matter.He might put his engagement to Jessie first and the claims of the widow and orphan second.

But the widow was his mother, and she had been the best and most loving of mothers to him.Jack's heart was set upon Jessie; but he loved that mother dearly, and he was also under the sway of a strong sense of duty.He knew well in what direction lay his plain duty for the present; and even apart from duty, he could not have neglected his mother.Jack would not have been Jack if such a thing had been possible to him.If Jessie did not wish to wait so long as might be necessary, he could set her free.Nothing could set aside the claims upon his strong young arm of his widowed mother.

In the midst of those cogitations Mokes came forward with an offer.He had talked much of "bad times" of late, and had, as we know, professed himself to be unable to give more than five shillings, to the lifeboat fund.It now appeared that he had a little more money somewhere within easy reach.He offered to buy up the whole contents of "Groates' Store," and even to take the house off the widow's hands, if she wished to move quickly into a less expensive domicile.He would pay down, for house and contents and custom, a certain round sum which, if not too liberal, might yet be looked upon as fair under the circumstances.At all events, it was more than would have been expected from Mokes.

Nobody who knew Mr. Mokes was deluded into supposing this to be an act of pure generosity.It might be granted that Mokes was sorry for the sudden death of his rival, and was concerned for the widow.

But, on the other hand, if Mokes himself neglected to purchase the goods and the custom and the remainder of the lease, somebody else might be expected to do so, and this would mean a continuance of opposition to Mokes' shop.Nay, it might mean a much more successful opposition if the shop should chance to fall into the hands of a better business man than Groates had proved to be.So Mokes was killing two birds with one stone when he made his offer.

"Seems to me it's the best thing we can do," Jack said to the Vicar, who had been throughout a kind adviser."That'll help us to clear off a lot of things, and we'll be able to start freer.And Mr. Ward has offered to take me on, with better pay than I'd hoped to be able to get."

"Ward, the grocer, at New Maxham?"

"Yes, sir.He's got the biggest business for twenty miles round, and everybody trusts him.Mother's very pleased.She says she'd sooner have me with him than with anybody, and they say he's offered it me for mother's sake."

"Well, you'll make it worth his while to have done so, Jack.If he is taking you now for your mother's sake, he will keep you by-and-by for your own.And we shall have you with us still.Only a mile off."

"Some ways I'd sooner have been farther off than New Maxham."

"You would?What, you want to see more of the world?"

"No, sir; it ain't that.Though mother did say a while ago that perhaps I'd ought.But I think I'd sooner have begun afresh in a new place.Mother wants to have a cottage here, and me to walk into New Maxham every day.She says she'll feel it more home-like."

"I dare say she will.And the walk is nothing for a hale young fellow like you.Do you good."

"Only, sir, there's Jessie."

"True, there is Jessie.What of her?"

"I shouldn't be right to let Jessie think I'd be free to marry her as soon as we'd thought of—and maybe—"

"Maybe she won't want to wait.Is that it?I don't think commonly that it is the woman who won't wait, do you?Try her, Jack."

"I couldn't leave mother with no one to take care of her.She's been a good mother to me, and I couldn't do it.Not for Jessie's sake even."

"I should have a very poor opinion of you if you could!Your mother ought to be your first consideration.The young folks will be able soon to fight their own way in life; but your mother will be getting older, and she will need your care.But what then?If you and Jessie have to wait longer than you had intended where is the harm?Just tell Jessie frankly how things are, and see what she will say.That is my advice.What does your mother think?"

"I haven't bothered her much, sir.She's been but poorly, and she's left things mostly to me.I'll have to tell her all soon.She knows we've got to part with the shop and live in a smaller house, and she knows about Mr. Mokes' offer and Mr. Ward's.She seems to cling-like to the thought of Old Maxham, and not to want to go away.But if things are to be up between me and Jessie, I'd sooner be a good way off."

"Have a talk with Jessie first, and see what she will say.I fancy you will see ahead more clearly then.After that you can go into things with your mother.But don't hurry on arrangements too fast.She has had a heavy blow, and you must give her time.People who are very brave at the first often suffer more afterwards."

"Yes, I think that's mother's way, sir.She seems sort of dazed, as if she couldn't take it all in."

"Don't force her yet.Mokes will not hurry you out of the house I am sure.No—so I thought.He really is kind-hearted at the bottom.Jack, I am going to give you back the sovereign that was your father's donation to the lifeboat fund.We can do without it now, and I think your mother's needs are greater.You needn't say anything about it to her, unless you wish.Since that gift of ninety pounds came in, it has all gone swimmingly, and I hope to have no further difficulties.The boat is to be sent as soon as it can be ready.So you need have no scruples."

Jack's hand went behind him.

"I couldn't, please, sir; I couldn't do it.Don't ask me.I know father liked to give that sovereign, and I shouldn't be happy to take it back.Please let it be."

"Well, if you choose.I must not insist.But if you change your mind in the course of a week or two, mind you tell me."

"And you've no notion who it was as gave the ninety pounds, sir?"

"I have had a good many notions, but no certainty.Nothing beyond conjecture, and conjecture isn't worth much.Besides, it really isn't our business if the good man wishes to keep his secret."

CHAPTER XXIII

WHAT JESSIE WOULD SAY

JACK felt that matters were coming to a crisis.He would do as the Vicar had advised.He would see Jessie, and would put before her the state of affairs, and would ask her to decide.

If she were willing to wait until he should be free to marry her, so much the better.Jack felt that he could wait any number of years, with a prospect of Jessie as his wife at the end.If she were not willing, then he would have to give her up.He could not in either case fail towards his mother.She was and had to be the first claim upon him.

It was not quite easy to get hold of Jessie alone.She was busy over her dressmaking, and he was busy over plans and accounts; and by a kind of tacit agreement, they had put off confabulations upon their own affairs until other people's affairs should be settled.But Jack now felt that a quiet talk with Jessie must come off before those affairs of other people could be entirely settled.The question of the future home of his mother and of himself might hang upon that quiet talk.

When once a person sets himself to have a thing done, it is usually not long in being brought about.Despite business and other difficulties, Jack found himself only two days later walking with Jessie outside Old Maxham, through a muddy field under a grey sky.

Jessie was unusually silent, seeming more disposed to listen than to talk, and Jack was desperately puzzled how to begin.He had conned over so often beforehand what he had to say that it had grown to look quite easy; and now he could remember nothing of it.So he and Jessie marched along together in solemn silence.

"I thought you wanted particular to speak to me," Jessie at length said.

"I thought you'd talk to me," Jack answered, cowardly still as to what he had to say.

"Me talk!Yes, of course, if you like."Then she started off full swing, and chattered on every variety of subject.She allowed Jack no loophole for his say, and this was worse than her previous silence.For some minutes Jessie rattled on about the lifeboat, and the anonymous gift, and who could have been the donor; and then she slid off to her own work, and said how nice it was, and how well she was paid, and how kind Mildred was in teaching her.Next she was skipping off to some fresh subject; but she had afforded Jack an opportunity, and Jack at last had the courage to avail himself of it.

"That's just what I'm thinking about."

"What, my dressmaking?"

"Yes, about what you've been saying.Things aren't the same now as they have been, and I want you to see it."

"I don't see the good," pouted Jessie."Look!Is that a chaffinch?"

"You've got to listen to me, Jessie, and I've got to say it.Don't you see, you can go on making money now and laying it by, and I can't.I shan't be able for ever so long.Every penny that I earn will have to go to keeping my mother in comfort, and the children.They'll just all depend on me."

"Well?"Jessie said.She hung her head so that he could not see her face, and the tone sounded cold.

"I can't tell how long it may be.And it don't seem to me—I should be right—to let you go on—not knowing—nor—"

Jack's faltering suggestions were nipped.Jessie raised her head, looked him in the face, and said tersely: "So you want to break it off?Very well."

"Jessie!"Jack had not expected this, and he was dumbfounded.He knew now how certain he had felt in his heart of what her answer might be, and the disappointment was great.A black cloud seemed to have settled down upon him.

Jessie said no more, and they walked on side by side.Jack's shoulders were rounded, and he dragged his feet like an old man.Jessie hung her head once more, and a keen observer, glancing under her hat-brim, might have detected a small smile quivering at the corners of her mouth.

"Well, you haven't said all you meant to say," she presently remarked.

"I told you—" Jack's voice was too husky to proceed.

"And I suppose you thought I'd want you to leave your mother to manage for herself, while you just went on working for me?A nice thing to think!"

Jessie's tone was full of scorn.This was not what Jack had expected her to say, either.He ventured to look in her direction, and saw two bright eyes sparkling with tears.

"Jessie—"

"Jack, you're a donkey; that's what you are!I wouldn't have thought you could have been so stupid!"Jessie stamped her foot upon the grass."I wouldn't!You ought to have more sense."

"I've got mother and the children to see to," Jack said helplessly.

"As if I didn't know that!And as if I'd ever look at you again, if you could go and leave your mother to get on as she could, while you were only thinking of yourself—well, and of me, if you like!That 'ud mean the same thing.If you could, I should despise you, Jack."

"Then you think I'm doing what's right?"

"You couldn't do anything else.I only wish I had a mother to work for.But I have—almost," she added, under her breath.

"Only, you know, it may mean putting off our being married for ever so long.I can't tell how long."

"There's no need to tell.Let it be put off.So much the better," declared Jessie."I'm in no hurry to get married.Why should I be?Girls like a bit of freedom first.And I'm comfortable as I am.As for your mother—if you and me ever do get married, why then she'll be my mother as well as yours, and I shall have a right to work for her too.And if we have a home, that home will be hers as well as yours and mine.So there!"

Jack was not to be at once pulled up out of despondency."And you're quite sure, Jessie—you don't think—you wouldn't rather give me up and take somebody else?"

"Yes, of course I would!That's just what I should like, most particularly," declared Jessie, with tartness."Get rid of you and take up with the first man I can find instead!It wouldn't matter who—not one bit!O no, anybody would do.I'm not difficult to please, am I?"Jessie broke into a queer laugh with a sound of tears in it."O dear, you men are funny!As if that was my way!"

"I don't want you to give me up.I'd wait any time for you.Only, it may be years and years."

"It won't be, though.I'm going to make lots of money, and I shall work all the harder now, thinking about your mother.Why, Jack, don't you know I'm pretty near as fond of her as you are, and I'd like nothing better in all the world than to give her a home and to make her happy.I've never had a mother of my own—anyhow, I can't remember her—and to be always with your mother would be lovely.She's the dearest thing, and she never grumbles.She isn't a scrap like aunt Barbara.The only thing is that you might get jealous.I'm not sure, but I almost think I love her more than I love you; and I don't mind telling you so, either.And as for giving you up,—if you are tired of me, I'll give you up this minute, and I'll say good-bye, and I'll tell you not to cross my path again in a hurry.And if you're not tired of me—why—then—things can go on as they have gone on.And if you can't lay by yet for me, I can lay by for your mother, and we can wait a while longer and make the best of it.So you needn't be a donkey again, Jock—that's all."

Jack's answer to these various "ifs," though wordless, was unmistakable.

He told his mother about his talk with Jessie.Jack had not meant to do so at first, only he was used to telling her everything that touched him closely.He tried not to let her know that the question of her support had played a prominent part; but her womanly penetration was a great deal too much for Jack's duller wits.A few adroit questions drew the whole from him, including Jessie's hot little speeches and loving words about herself.A curious light came into Mrs. Groates' face, and her eyes, which had of late been dimmed with tear-shedding, shone again with almost their old look.

"And you think I'm going to sit with my hands before me, Jack, and you do all the work?"

"Why, no; you'll keep things going in the house, and there 'll be the children to see to.You'll find plenty to do,—no fear!"

"I shall take a share of earning money too.I can tell you that.I don't mean to be a useless burden on anybody.Not even on you."

"You'd never be useless, come what might.And it isn't only me that's going to work.Miss Pattison has offered to teach Mimy dressmaking, so that by-and-by she can get work in some of the New Maxham shops.We didn't mean to bother you about it for a day or two, but Mimy likes the notion, and I don't think you'll have anything against it.Just like Miss Pattison, isn't it?And Ted will be through his schooling in less than three months, and then we'll have to find something for him to do too.He's a handy little chap, you know.But you and the three little ones are going to be my charge,—till they can begin to work for themselves too, which won't be yet awhile.And you will be my charge always, mother,—mine and Jessie's too, in time, for she says so."

"Bless you both for meaning it!All the same, I'm going to take my share."

"I'll not have you go out charing.Nothing of that sort.You're not fit for rough work."

"There's things enough to be done.I'm used to turn my hand to most things.I'm good at fine needlework; and I can cook first-rate; and I shouldn't mind a spell at nursing now and then.You won't keep me in idleness, Jack; thank you all the same.And I'll try to get some needlework."

Jack protested in vain; and as days went by, he became convinced that his mother would really be the happier for having a certain amount of employment.The children would be away a great part of the day, except in holiday time, and the tiny cottage which was to be their home would scarcely afford scope enough for so active a little person in mind and body as Mrs. Groates.

It was quite true, as she had told Jack, that she was not only a very good needle-woman, but also an efficient cook, and a reliable nurse—not trained up to full modern requirements, but experienced in divers illnesses.These gifts might in coming months be turned to good account.

Meanwhile, the move out of the old home into a new one had to be done.A small cottage, on the outside border of Old Maxham, had been found for a moderate rent; and enough furniture to make it habitable was taken thither from "Groates' Store," the rest being parted with to Mr. Mokes, together with the stores of grocery and aught else that the shop held.

The act of removal, and settling in, helped to rouse Mrs. Groates, and to give her new interests in life.It was a pretty little cottage, with small but not inconvenient rooms, and a tiny garden behind, which Jack proposed to cultivate in leisure hours.

Since Jessie had not taken him at his word, and had not wished to break off the engagement, he was glad still to make his home in Old Maxham.He was by nature very much of a "home-boy," and he did not love change or novelty.To be within easy reach of Jessie was cheering; and the daily walk in and out of New Maxham would do him no harm.As Mr. Gilbert had foretold, Jack gave great satisfaction at the grocer's where his work now lay; and very soon, from having been taken on for his Mother's sake, he was highly valued for his own.